When is Cash Not Yours? A Landmark Japanese Case on Embezzlement

Imagine a common business scenario: a client gives an agent or broker a sum of money with clear instructions to use it for a specific transaction, such as purchasing goods or real estate on the client's behalf. The agent, however, uses the funds for their own personal expenses. Is this a criminal act of embezzlement, or is it merely a civil breach of contract, a debt to be repaid? The answer hinges on a surprisingly complex legal question: who "owns" money once it has been physically handed over to another person?

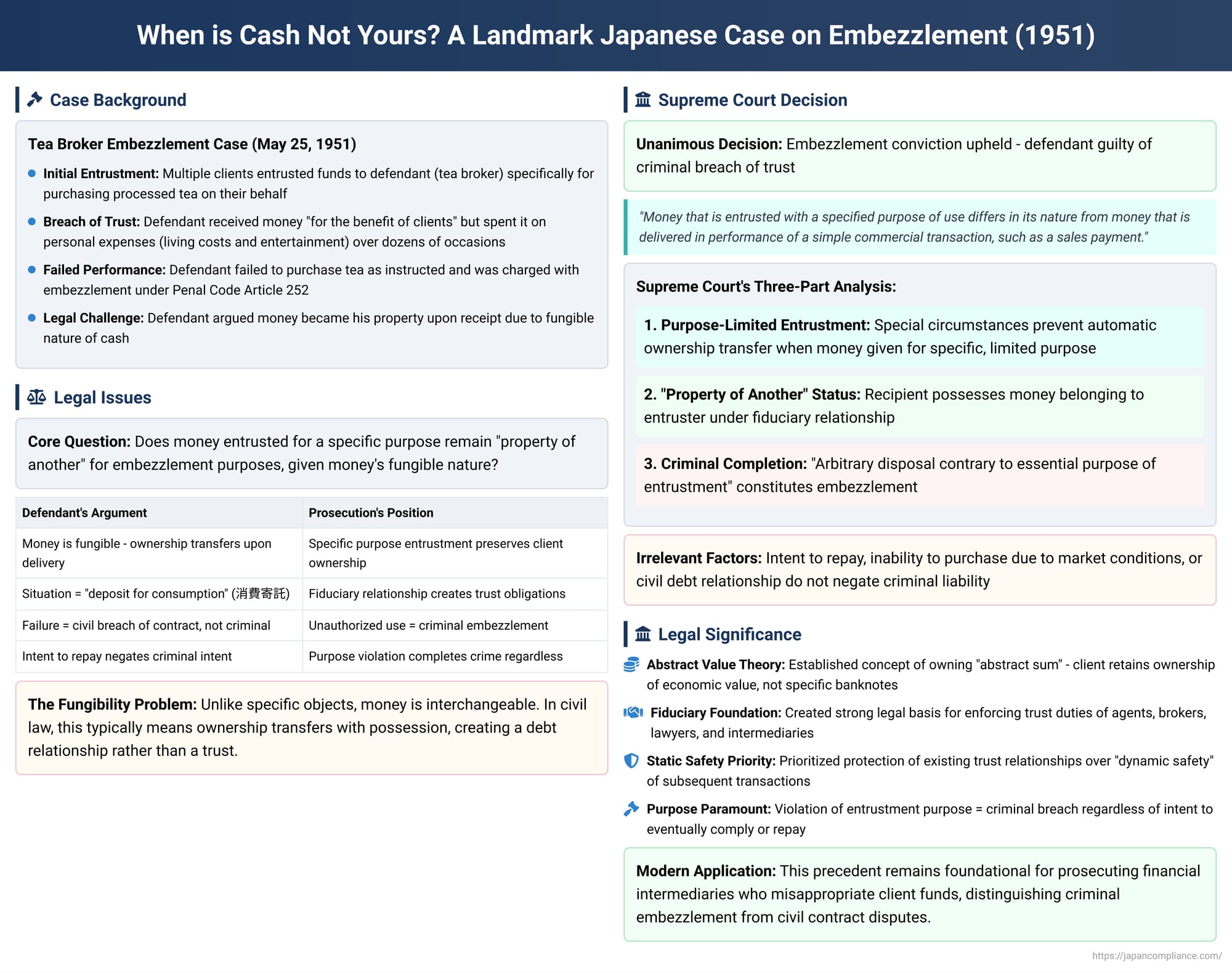

This issue was the subject of a foundational decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on May 25, 1951. The case, involving a tea broker who spent his clients' funds on himself, established a crucial principle for the crime of embezzlement. The Court ruled that when money is entrusted for a specific purpose, it remains the "property of another," and using it for any other purpose is a crime, regardless of its fungible nature.

The Legal Puzzle: The Fungibility of Money

The core of the legal problem lies in the unique nature of money. Unlike a specific, identifiable object like a watch or a car, money is a "fungible good" (daitaibutsu)—any one unit (like a 10,000 yen note) is perfectly interchangeable with another.

In civil law, this has led to a general principle that when money is delivered from one person to another, ownership typically transfers along with possession. The recipient does not hold the specific banknotes in trust; they acquire ownership of the funds and, in return, incur a civil debt to the giver for an equivalent amount.

This principle formed the basis of the defendant's argument in this case. He contended that once he received the cash from his clients, it became his property. His failure to buy the tea, he argued, was simply a breach of contract and a failure to repay a debt—a civil matter, not a criminal one. He claimed his situation was akin to a "deposit for consumption" (shōhi kitaku), where the recipient is legally free to use the funds as they see fit.

The Facts of the Case: The Tea Broker's Betrayal

The defendant in the case was a broker who had been hired by several clients to purchase processed tea for them. The clients entrusted him with funds specifically for this purpose. The defendant received the money and was holding it "for the benefit of the clients."

Instead of executing the purchases, however, the defendant, over dozens of occasions, spent the money on his own personal needs, including living expenses and entertainment. When he failed to deliver the tea, he was charged with embezzlement under Article 252 of the Penal Code.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Purpose Restricts Ownership

The Supreme Court rejected the defendant's argument and upheld his conviction for embezzlement. The Court's decision drew a sharp distinction between money given in a simple transaction and money entrusted for a specific purpose.

The Court announced its landmark principle:

"Money that is entrusted with a specified purpose of use differs in its nature from money that is delivered in performance of a simple commercial transaction, such as a sales payment."

The Court ruled that when funds are given for a limited and specific purpose, special circumstances do not exist to automatically transfer ownership. In such a case, the recipient "should be understood to be a person who possesses 'the property of another'" as defined by the embezzlement statute.

Therefore, the Court concluded, when the recipient "arbitrarily disposes of that money in a manner contrary to the essential purpose of the entrustment, the crime of embezzlement is constituted." The defendant's intent to eventually repay the money or the fact that he was unable to purchase the tea due to market conditions was irrelevant. The crime was complete the moment he spent the entrusted funds for his own unauthorized purposes.

Analysis: The Theory of "Abstract Value" Ownership

The Supreme Court's 1951 decision is legally sound, but it requires a sophisticated understanding of ownership to reconcile it with the fungible nature of money. If the specific banknotes given to the defendant are not the "property" in question, what is?

The dominant legal theory in Japan, which this ruling implicitly supports, is the concept of owning an "abstract sum" or "amount of money."

- When a client entrusts money to a broker for a specific purpose, the client no longer owns the particular physical banknotes.

- However, they retain legal ownership over the abstract economic value that the money represents.

- The broker, in turn, does not become the owner of the funds. They become the possessor of a sum of money which they hold in trust for the client. Their duty is to preserve that specific economic value for its designated purpose.

This elegant theory solves the legal puzzle. It respects the fungible nature of cash—the broker could, for example, exchange a 10,000 yen note for two 5,000 yen notes without committing a crime. But it also protects the client's property rights by making it a crime for the broker to diminish the total abstract value entrusted to them for their own personal benefit.

This approach prioritizes the "static safety" of property in criminal law—that is, the protection of the existing trust relationship between the client and the agent. This can be contrasted with the "dynamic safety" of transactions often prioritized in civil law, which might focus more on protecting a third party who innocently receives the embezzled money from the agent in a subsequent transaction.

Conclusion: A Foundation for Fiduciary Duty

The 1-951 Supreme Court decision is a foundational precedent for the crime of embezzlement in Japan. It authoritatively established that when money is entrusted for a specific, limited purpose, it does not become the personal property of the recipient. It remains the "property of another" in the eyes of the criminal law, and the recipient holds it in a position of fiduciary trust.

The ruling's core principle is that the purpose of the entrustment is paramount. Violating that purpose by spending the funds for unauthorized personal use is a criminal breach of trust, constituting embezzlement. This decision provides a powerful and enduring legal basis for enforcing fiduciary duties, ensuring that agents, brokers, lawyers, and anyone entrusted with funds for a specific use can be held criminally accountable for betraying that trust.