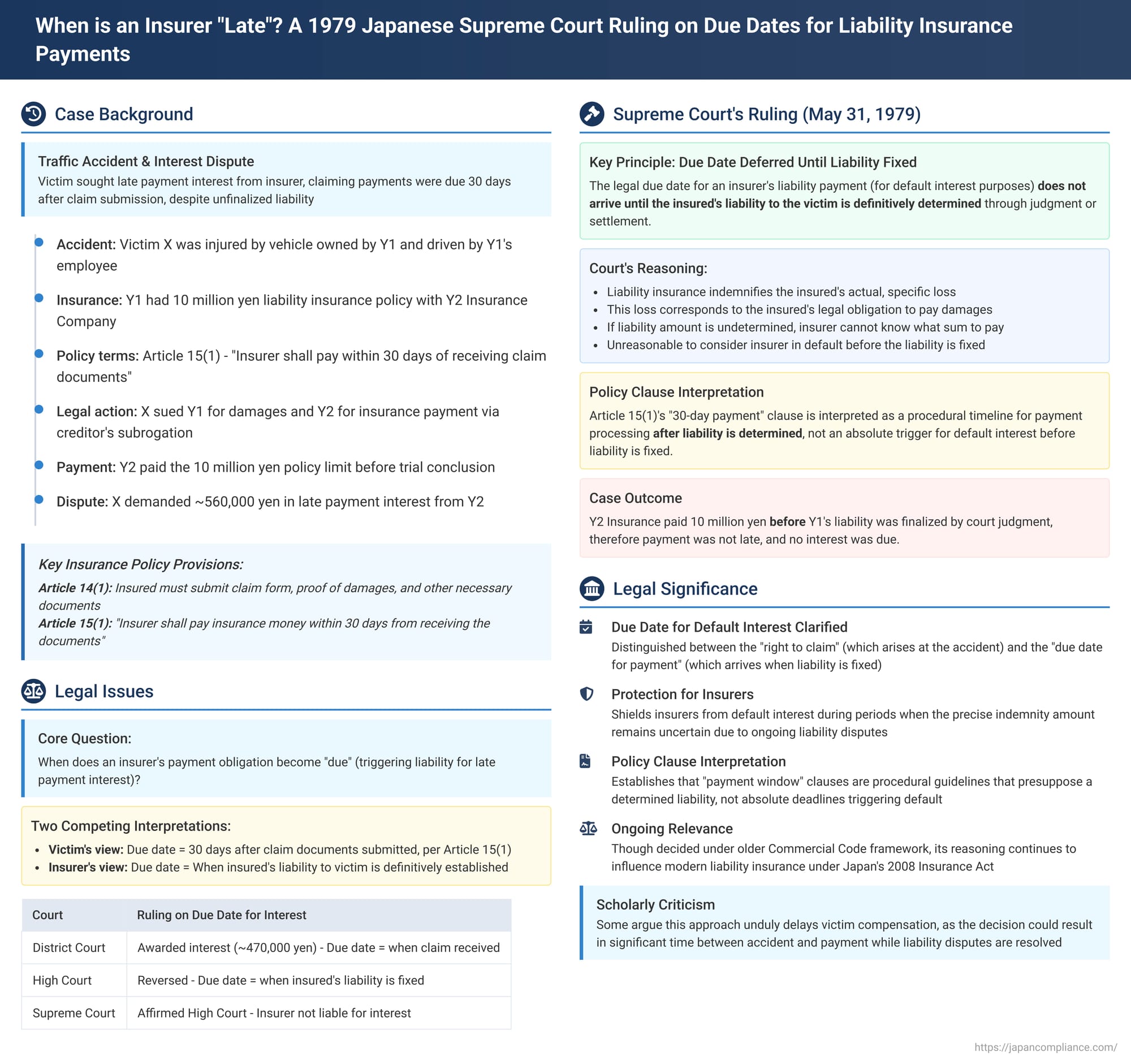

When is an Insurer "Late"? A 1979 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Due Dates for Liability Insurance Payments

Judgment Date: May 31, 1979

Court: Supreme Court, First Petty Bench

Case Name: Damages Claim Case

Case Number: Showa 52 (O) No. 903 of 1977

Introduction: The Timing of Insurer Payments and Default Interest

Liability insurance is a cornerstone of risk management, designed to protect an insured individual or business against the financial consequences of being held legally responsible for causing harm or loss to a third party. A critical aspect of any insurance contract is determining when the insurer's obligation to pay a claim actually becomes "due." This is not merely an academic question; if an insurer fails to pay by the due date, it can be deemed in default and may become liable for late payment interest (遅延損害金 - chien songaikin) on the claim amount.

However, in the context of liability insurance, pinpointing this due date can be complex. The insurer's duty to indemnify its insured is often contingent upon the insured's own liability to the injured third party being clearly established and quantified. Standard insurance policies typically include clauses that outline procedures for submitting a claim and may stipulate a timeframe (e.g., 30 days) within which the insurer is expected to make payment after receiving the necessary claim documents. Does this mean the insurer is automatically in default if it doesn't pay within that specified window, even if its insured's liability to the third-party victim is still being disputed or has not yet been finalized by a court judgment or formal settlement? This crucial question regarding the due date for an insurer's payment obligation under an automobile third-party liability insurance policy was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant 1979 decision.

The Factual Scenario: An Injury, an Insurance Claim, and a Dispute Over Interest

The case arose from a traffic accident where Mr. X was seriously injured after being struck by a vehicle owned by Mr. Y1 and driven by Mr. Y1's employee. Mr. Y1 held an automobile third-party liability insurance policy with Y2 Insurance Company, with a policy limit of 10 million yen.

Mr. X initiated a lawsuit, seeking damages directly from Mr. Y1 (the vehicle owner and tortfeasor). In the same legal action, Mr. X also included a claim against Y2 Insurance Company. He sought to exercise Mr. Y1's rights to the insurance money by "stepping into Mr. Y1's shoes" through a legal mechanism known as creditor's subrogation (a right allowing a creditor to pursue a claim that their debtor has against a third party).

Before the first trial in this consolidated lawsuit concluded, Y2 Insurance Company paid out the full policy limit of 10 million yen. (The judgment text indicates this payment was made to Mr. Y1, the insured, who would then use it to compensate Mr. X; for the purpose of the interest claim, the core issue is when Y2's obligation to make this payment became overdue).

With the principal insurance amount having been paid, Mr. X's claim against Y2 Insurance Company was effectively reduced to a demand for late payment interest. He alleged that Y2 Insurance Company had been in default for a certain period before it finally made the 10 million yen payment, and he sought approximately 560,000 yen in accrued interest for this alleged delay.

The insurance policy in question, based on standard automobile insurance general clauses revised in 1965, contained the following relevant provisions regarding claims:

- Article 14, Paragraph 1: Stipulated that if the insured (Mr. Y1) wished to seek indemnification under the policy, they were required to submit to the insurer (Y2 Insurance Company) a claim form, "documents proving the amount of damages," and any other documents or evidence the insurer deemed particularly necessary, along with the insurance policy certificate, within 60 days of the accident (or within an extended period if approved in writing by the insurer).

- Article 15, Paragraph 1: Stated that the insurer (Y2 Insurance Company) "shall pay the insurance money within 30 days from the date of receiving the documents or evidence stipulated in the preceding article."

The Core Legal Question: When Does an Insurer's Payment Obligation Become Overdue, Triggering Late Payment Interest?

The central dispute was the determination of the "due date" (履行期 - rikōki) for Y2 Insurance Company's payment obligation. Specifically:

- Did Y2 Insurance Company's obligation to pay the 10 million yen become legally "due" – in a manner that would trigger liability for late payment interest if not met – simply 30 days after it received Mr. Y1's (or Mr. X's subrogated) claim documents, regardless of whether Mr. Y1's actual legal liability to Mr. X had been definitively finalized by a court judgment or settlement at that point?

- Or, did the due date for Y2 Insurance Company's payment (for the purpose of calculating default interest) only arrive when Mr. Y1's liability to Mr. X was formally and quantitatively fixed? If the latter, then any payment made by Y2 Insurance Company before that point of finalization would not be considered "late," and no default interest would accrue.

Lower Court Rulings – A Split Decision on the Due Date

The lower courts came to different conclusions on this critical issue:

- Court of First Instance (Tokyo District Court): This court ruled that Y2 Insurance Company was liable for a portion of the late payment interest claimed by Mr. X (awarding approximately 470,000 yen).

- Its reasoning was that Mr. Y1's right to claim insurance money from Y2 Insurance Company arose as soon as Mr. Y1 incurred legal liability to Mr. X due to the accident. The court believed that the determination of the specific amount of this insurance claim could be made directly between Mr. Y1 (the insured) and Y2 Insurance Company (the insurer) as part of the claims process itself. It did not consider a prior final judgment or formal settlement between Mr. Y1 and Mr. X to be a necessary precondition for Mr. Y1's insurance claim against Y2 to mature.

- Furthermore, the first instance court interpreted Article 15, Paragraph 1 of the policy (the "30-day payment" clause) as merely an internal administrative processing guideline for the insurer, not as the definitive trigger for the legal due date of the payment obligation. It held that Y2 Insurance Company was legally in default from the time it effectively received the claim (which, in this subrogation lawsuit, was when the complaint was served upon it).

- Mr. Y1 (the tortfeasor) did not appeal the judgment against him, so his liability to Mr. X for the principal sum of damages (41.5 million yen, as awarded by the first instance court) became final. However, Y2 Insurance Company appealed the part of the judgment that held it liable for late payment interest. Mr. X also filed a cross-appeal against Y2 Insurance Company, presumably concerning the amount of interest.

- Appellate Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court reversed the first instance court's decision regarding Y2 Insurance Company's liability for interest. It dismissed Mr. X's claim against Y2 for this interest.

- The High Court reasoned that the nature of liability insurance is to indemnify the insured for losses they suffer as a result of being held legally liable to a third party. It emphasized that the insurer's duty to indemnify its insured for a specific monetary amount cannot realistically be fulfilled until the insured's legal liability to the victim – both its existence and its precise monetary content – has been definitively fixed.

- Therefore, the High Court concluded, the legal due date for the insurer's payment obligation under a liability insurance policy does not arrive until the amount of damages owed by the insured to the victim has been formally determined, typically by a settlement between the insured and the victim, or by a final court judgment.

- In this case, Y2 Insurance Company had paid the full 10 million yen policy limit before the first instance court's judgment against Mr. Y1 (which fixed his liability to Mr. X) became final. Thus, according to the High Court, Y2 had made its payment before its obligation had even become legally "due" for the purpose of triggering default interest. Consequently, Y2 was not in default and owed no late payment interest.

Mr. X then appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (May 31, 1979): Due Date for Insurer Default is Deferred Until Insured's Liability is Fixed

The Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, dismissed Mr. X's appeal. It upheld the Tokyo High Court's decision, thereby affirming that Y2 Insurance Company was not liable for the late payment interest claimed. The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

The Nature of Liability Insurance and the Insured's Claim Right

The Court began by acknowledging the fundamental nature of liability insurance contracts like the one held by Mr. Y1. Such policies are designed to indemnify the insured for the financial losses they incur specifically because they have become legally liable to compensate a third party for damages arising from an accident.

The Supreme Court agreed that the insured, Mr. Y1, acquired a right to claim insurance money from his insurer, Y2 Insurance Company, (up to the policy limit) as soon as the covered accident occurred for which he was potentially liable. This right was exercisable.

Distinction Between the Right to Claim and the Payment Due Date (for Default Interest)

However, the Court drew a crucial distinction: the mere acquisition of this right to claim by the insured does not automatically mean that the legal due date for Y2 Insurance Company's payment obligation (the date from which default interest would begin to accrue if payment was not made) arrived at the same moment. Nor did it mean the due date arrived simply upon Mr. Y1 (or Mr. X via subrogation) submitting a claim, or even after the expiry of a fixed period (like the 30 days mentioned in Article 15(1)) following claim submission, if the core issue of Mr. Y1's liability amount was still unresolved.

The Indemnifiable Loss Must Be Quantitatively Determined

The Supreme Court emphasized the following points:

- The general principle of indemnity insurance is that it aims to compensate the insured for the actual, specific loss they have suffered.

- In the context of a liability insurance contract, this "loss" directly corresponds to the amount of damages the insured is legally obligated to pay to the injured third party.

- Therefore, even if it is clear that the insured (Mr. Y1) has incurred a legal liability to the third-party victim (Mr. X) as a result of the accident, as long as the specific monetary amount of that liability has not been definitively and quantitatively determined, the precise amount of financial loss that the insurer (Y2 Insurance Company) is contractually bound to indemnify under the policy also remains undetermined. At that stage, the insurer cannot reliably ascertain the actual, final sum of insurance money that it should properly pay.

Unreasonableness of Imposing Early Default on the Insurer

Given this dependency, the Supreme Court stated that it would be unreasonable to hold the insurer (Y2) liable for having been in default (and thus liable for late payment interest) from an earlier point in time (such as 30 days after the initial claim submission) when the core component of its indemnification duty – the finalized and quantified amount of its insured's liability to the victim – was still unknown, in dispute, or not yet formally established.

Conclusion on the Due Date for Default Interest Purposes

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court laid down a general principle:

Unless the insurance policy explicitly and unambiguously stipulates a different arrangement for the accrual of default interest, the legal due date for the insurer's payment obligation under a liability insurance policy (for the purpose of triggering liability for late payment interest) does not arrive until the amount of the insured's liability for damages to the third-party victim is definitively determined. This determination would typically occur through a final court judgment against the insured, a formal settlement agreement between the insured and the victim, or a similar process that fixes the quantum of the insured's liability.

Interpretation of the Policy's Claim Procedure Clauses (Articles 14 & 15)

The Supreme Court viewed the policy clauses regarding claim submission procedures (Article 14, Paragraph 1 – requiring submission of "documents proving the amount of damages") and the insurer's 30-day payment window (Article 15, Paragraph 1) as being premised on this underlying principle. These clauses were interpreted as outlining the process for making a claim and the insurer's general timeline for payment once the necessary information, including the determined amount of the insured's liability, is available. They were not seen as creating an absolute due date for default interest purposes that would kick in before the insured's own liability to the victim had been properly quantified and finalized.

Application to the Facts of the Case

In Mr. X's case, the liability of Mr. Y1 (the insured) to Mr. X, and particularly the amount of that liability, was actively disputed and was only definitively established by the first instance court's judgment (which became final for Mr. Y1 because he did not appeal it). Y2 Insurance Company had already paid the full 10 million yen policy limit to Mr. Y1 before this judgment against Mr. Y1 became final.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded, Y2 Insurance Company had made its payment before its payment obligation (for the purpose of triggering default interest) had even become legally "due" according to the principles it had just articulated. Consequently, Y2 Insurance Company was not in default and owed no late payment interest to Mr. X (who was claiming via subrogation).

Analysis and Implications of the Ruling

The 1979 Supreme Court decision significantly clarified the timing of an insurer's payment default in the context of third-party liability insurance in Japan, particularly under policy terms prevalent at that time.

1. Defining the "Due Date" for Insurer Default in Liability Claims:

The core takeaway from this judgment is the distinction it draws between an insured's right to make a claim against their liability insurer (which may arise at the time of the accident giving rise to potential liability) and the legal due date for the insurer's payment obligation, specifically for the purpose of calculating whether the insurer is in default and owes late payment interest. The Court held that this latter due date, for default purposes, does not arrive until the insured's underlying liability to the injured third party has been specifically quantified and definitively determined.

2. Protection for Insurers from Premature Default Claims:

This ruling provides a degree of protection for liability insurers. It prevents them from being deemed in default (and thus being held liable for potentially substantial late payment interest) during periods when the precise amount they are ultimately required to indemnify remains uncertain due to ongoing disputes or legal proceedings between their insured and the injured third-party victim. This acknowledges the practical reality that an insurer cannot definitively pay out a claim whose ultimate value (contingent on the insured's liability) is not yet fixed.

3. Impact on the Interpretation of Standard Policy Clauses like "30-Day Payment Windows":

The Supreme Court interpreted typical policy clauses that stipulated a relatively short payment window for the insurer (e.g., "30 days after receipt of claim documents") not as absolute deadlines that would trigger default interest if the underlying liability of the insured was still unknown or undetermined. Instead, these clauses were seen as procedural timelines that primarily govern the insurer's payment processing once the core condition – the fixation of the insured's quantifiable liability – is met, or once the necessary information to assess an already determined liability is provided to the insurer.

4. Criticisms and Alternative Perspectives (Highlighted in Legal Commentary):

Legal commentary (such as that in the PDF source provided with this case) has critically examined the Supreme Court's reasoning and its potential consequences.

- Some scholars have argued that it should be possible for the insurer and the insured to determine an appropriate amount for indemnification based on the known facts of the accident and an assessment of likely liability, even before a final judgment or formal settlement is reached between the insured and the third-party victim. Requiring the victim-insured liability to be absolutely finalized first could, in some views, unduly delay the insured's (and by extension, the victim's, if they are relying on subrogation) access to insurance funds.

- The policy in this 1979 case required the insured to submit claim documents, including "documents proving the amount of damages," generally within 60 days of the accident. Critics have pointed out that obtaining a final court judgment or a formal settlement often takes considerably longer than this 60-day period. This apparent mismatch has led some to question whether the policy drafters themselves truly envisaged such a late trigger (i.e., final fixation of liability) for the insurer's core payment processing obligations to commence.

- The outcome of the Supreme Court's ruling could be problematic for ensuring prompt victim relief or insured protection if the liability insurance policy in question does not contain a provision for a direct claim right by the victim against the insurer, or if there is no robust system for the insurer to make advance payments or interim payments while the underlying tort liability is still being finalized. It effectively ties the "due date" of the insurer's payment (for default purposes) to the often slower timeline of resolving the primary tort liability dispute.

5. Comparison with the 1982 Supreme Court "No Action Clause" Case (from the user's previous file, h33.pdf):

It is instructive to compare this 1979 Supreme Court ruling with the Court's 1982 decision concerning a specific "no action clause" (which explicitly stated that the insured's claim right against the insurer only "arises" when the insured's liability to the victim is fixed). In the 1982 case, the Supreme Court allowed a victim's subrogated claim against the insurer to proceed concurrently with the victim's primary claim against the tortfeasor, by treating the subrogated claim as one for future performance that would mature upon the court's fixing of the tortfeasor's liability in that same joined action.

The 1979 case, however, was focused specifically on the narrower question of when late payment interest begins to accrue if the policy does not contain such an explicit "arising" clause but rather contains more standard claim processing clauses. The 1979 decision effectively sets a later trigger for the accrual of default interest (i.e., the definitive fixation of the underlying liability) than the 1982 decision might imply for the mere exercisability of what the 1982 court called a (perhaps conditional) insurance claim right. The two cases, while related, address slightly different facets of the timing of insurer obligations.

6. Relevance in the Modern Legal Era (Post-Insurance Act of 2008):

Japan's comprehensive Insurance Act of 2008 now includes specific statutory provisions regarding the timing of insurance payments by insurers (see, for example, Article 21 of the Act). This Act generally requires an insurer to make payment within a reasonable period after it has completed the investigation necessary to ascertain the loss, or within a period that may be specified in the policy (provided that specified period is itself reasonable). While this 1979 Supreme Court judgment was decided under the older Commercial Code framework, its fundamental reasoning – particularly its emphasis on the fact that in liability insurance, the insurer's obligation to pay a determined amount is intrinsically linked to the determination of the insured's underlying liability to a third party – may still inform how concepts like a "reasonable period" for payment or specific policy clauses are interpreted by courts today, especially when considering the precise point at which an insurer should be deemed in default and liable for late payment interest if the core liability amount that triggers the indemnity remains unfixed.

Conclusion

The May 31, 1979, Supreme Court of Japan decision provided crucial clarification on a key aspect of third-party liability insurance under the policy terms prevalent at that time. It established that the insurer's obligation to pay its insured (and consequently, its liability for late payment interest if payment is delayed) does not become legally "due" until the insured's own legal liability to the injured third party has been specifically quantified and definitively determined – typically by a final court judgment or a formal settlement agreement.

Standard policy clauses that required the insured to submit claim documents within a certain period and the insurer to make payment within a subsequent short window (e.g., 30 days) were interpreted by the Court as procedural steps that largely presupposed this underlying determination of the insured's liability. These clauses did not, in themselves, trigger an immediate default by the insurer if that fundamental determination of liability was still pending.

This ruling prioritized the insurer's need to have a confirmed and quantified basis for indemnification before being considered in default of its payment obligation. While this approach aimed to ensure that insurers are not unfairly penalized for delays that are outside their direct control (i.e., delays inherent in the process of fixing the primary tort liability between their insured and the victim), the decision also highlighted potential challenges for insured parties and, by extension, for injured victims seeking the promptest possible financial relief under such liability insurance structures, particularly if mechanisms for advance payments or direct victim claims against the insurer were not robustly available or utilized. The judgment remains an important reference for understanding the temporal dynamics of insurer liability in third-party claims.