When is a 'Thank You' a Bribe? Japan's Landmark Case on Gifts to Public School Teachers

In many cultures, giving gifts is a deeply ingrained way to express gratitude, respect, or goodwill. This is particularly true in Japan, where seasonal and situational gift-giving, or zōtō, has long been a part of the social fabric. But what happens when this custom intersects with the strict laws against public corruption? When does a gift to a public official—like a school teacher—cross the line from an acceptable "social courtesy" into a criminal bribe?

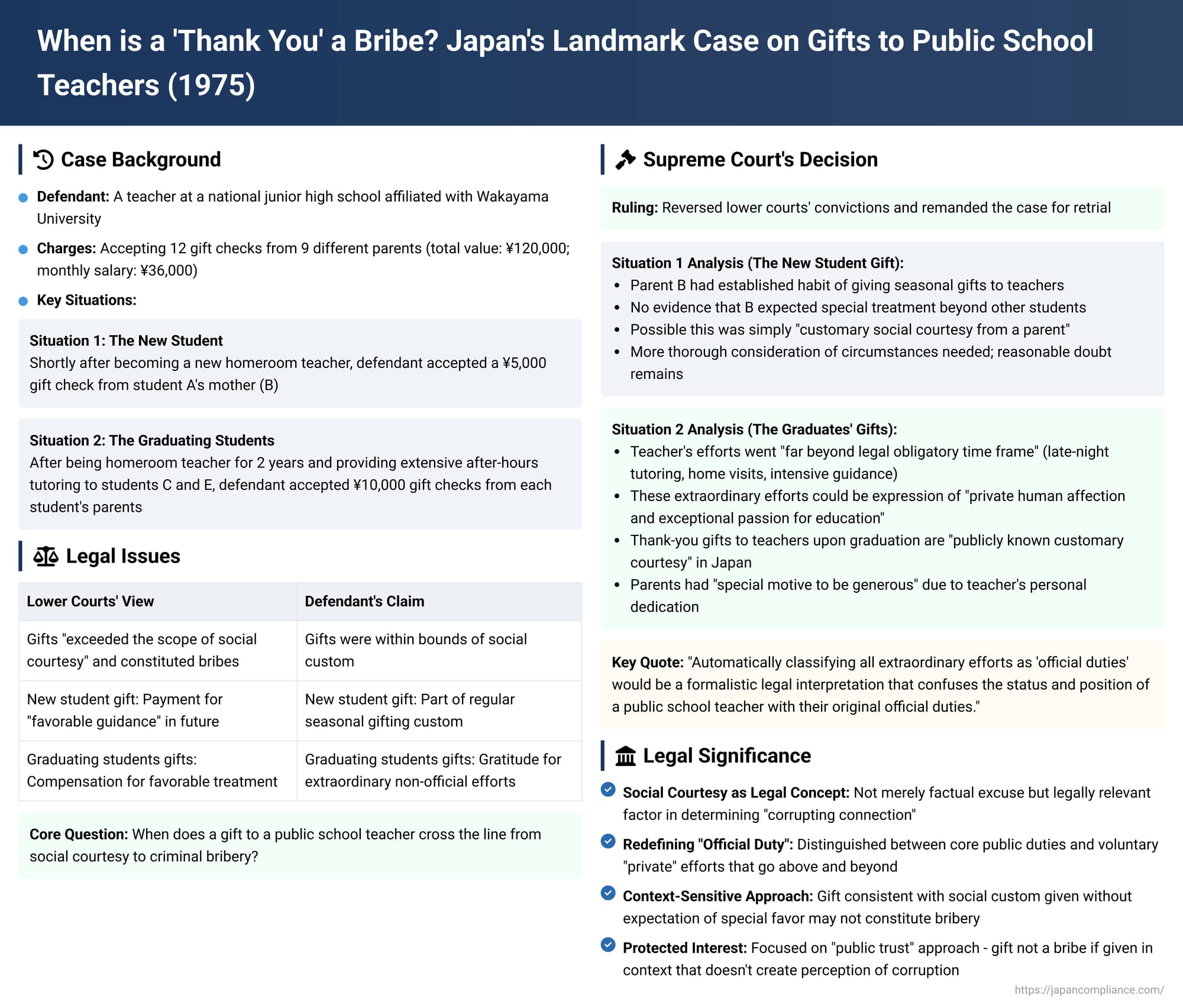

This sensitive and complex question was at the center of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 24, 1975. In a case involving a junior high school teacher who accepted gift checks from his students' parents, the nation's highest court provided its first detailed analysis of the issue. The ruling, which ultimately acquitted the teacher, established a nuanced precedent for distinguishing between legitimate social custom and criminal bribery, one that remains highly influential today.

The Facts: The Teacher and the Gift Checks

The defendant was a teacher at a national junior high school affiliated with Wakayama University. He was charged with bribery for accepting twelve gift checks from nine different parents over a period of time. His monthly salary was approximately 36,000 yen, while the total value of the checks was 120,000 yen. The Supreme Court's analysis focused on two distinct situations for which he had been convicted by the lower courts:

- Situation 1: The New Student. Shortly after becoming the new homeroom teacher for a student named A, the defendant accepted a 5,000 yen gift check from the student's mother, B.

- Situation 2: The Graduating Students. As two of his students, C and E, were graduating, the defendant accepted a 10,000 yen gift check from each of their parents (D and F, respectively). He had been their homeroom teacher for two years and had provided them with extensive, voluntary after-hours tutoring and academic guidance.

The Lower Courts' Verdict: "Exceeding Social Courtesy"

The lower courts found the teacher guilty in these instances. The High Court ruled that in both situations, the gifts "exceeded the scope of social courtesy" and were therefore illegal bribes.

- In the case of the new student, the gift was seen as an attempt to receive "favorable guidance" in the future.

- In the case of the graduating students, the gifts were interpreted as a "thank you" for the favorable guidance the teacher had provided during their time at the school.

The defendant appealed, arguing that the gifts were within the bounds of social custom and, particularly in the case of the graduating students, were expressions of gratitude for his extraordinary, non-official efforts.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: A Two-Part Analysis

In a groundbreaking decision, the Supreme Court overturned the convictions and sent the case back for retrial, finding that the lower courts had too hastily concluded the gifts were bribes and that reasonable doubt remained in both scenarios. The Court analyzed each situation separately, creating a sophisticated framework for assessing such cases.

Analysis of Situation 1 (The New Student's Gift)

The Court found that the lower courts had failed to consider the full context of the gift.

- Social Custom as Context: The Court noted that the parent, B, had an established personal habit of giving seasonal gifts and making greeting-gifts to her children's teachers at the beginning of each school year.

- Lack of Corrupt Intent: There was no specific evidence to suggest that B expected "special consideration or benefit beyond that given to other students" in exchange for the gift.

- The Conclusion: The Court ruled that it was entirely possible this was simply a "customary social courtesy from a parent" to a new teacher. To immediately conclude that it was a quid pro quo payment for his official duties was not possible without a more thorough consideration of all circumstances, such as the gift-giving practices of other parents and with other teachers. Reasonable doubt remained.

Analysis of Situation 2 (The Graduates' Gifts)

The Court's reasoning for the second situation was even more profound and has had a lasting impact on how the "official duties" of some public servants are defined.

- Public Duty vs. Private Passion: The Court questioned the very premise that the gifts were for the teacher's "official duties". It highlighted the extensive, voluntary support the teacher had provided, which went "far beyond the legal obligatory time frame" and was "above and beyond the normal social expectation" for a school teacher. His efforts included late-night tutoring during his own on-duty overnights, visiting students' homes to discuss study methods with them and their tutors, and providing intensive guidance on high school selection.

- "Private Human Affection": The Court suggested that automatically classifying all of these extraordinary efforts as "official duties" would be a "formalistic legal interpretation" that "confuses the status and position of a public school teacher with their original official duties". Instead, the Court offered that these actions could be seen as an expression of "private human affection and an exceptional passion for education," separate from his public role.

- A "Special Motive" for Gratitude: The Court also acknowledged that giving thank-you gifts to teachers upon graduation is a "publicly known customary courtesy" in Japan. Given the teacher's extraordinary and personal efforts, the Court found it was a "natural human sentiment" for these parents to feel deep "admiration and gratitude" and to have a "special motive to be generous" in their customary thank-you gift.

- The Conclusion: The Court found there was reasonable doubt that the gifts were for his public duties. They could just as likely have been an expression of gratitude for his private dedication and a gesture of personal respect.

Deeper Implications: Bribery Law and Social Norms

This 1975 decision is significant for establishing that "social courtesy" is not merely a factual excuse but a legally relevant concept in bribery cases.

- The Role of "Social Courtesy": It functions as a key factor in determining whether a "corrupting connection" exists between a gift and an official's duties. A gift that aligns with established social custom and for which there is no evidence of an expectation of special treatment may not be a criminal bribe.

- The Definition of "Official Duty": The ruling's most impactful aspect is its willingness to distinguish between an official's core public duties and their voluntary, "private" efforts that go above and beyond. This has major implications for public servants in roles like teaching, where personal dedication and extra effort are often socially expected but may fall outside the strict definition of their job description for the purposes of criminal law.

- The Protected Interest of Bribery Law: The case also touches on the ongoing debate about what bribery law is meant to protect. Is it the objective "fairness" of public duties, or the more subjective "public's trust" in that fairness? The Court's focus on customs and the specific motivations of the parents suggests an approach more aligned with protecting public trust, where a gift is not a bribe if it is given in a context that does not create a perception of corruption.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1975 ruling on the teacher's gifts remains a vital precedent for drawing the difficult line between bribery and social custom in Japan. It established two critical principles: first, a gift that is consistent with social custom and given without an expectation of special favor may not be a bribe; and second, a gift given in genuine gratitude for extraordinary efforts that fall outside an official's formal public duties may not be considered a bribe at all. The decision represents a nuanced, context-sensitive approach to bribery law, recognizing that not every gift to a public official is inherently corrupt, especially when it is rooted in genuine gratitude for exceptional and personal dedication that transcends the formal boundaries of duty.