When is a Public Duty Just 'Business'? A Landmark Japanese Ruling on Obstruction

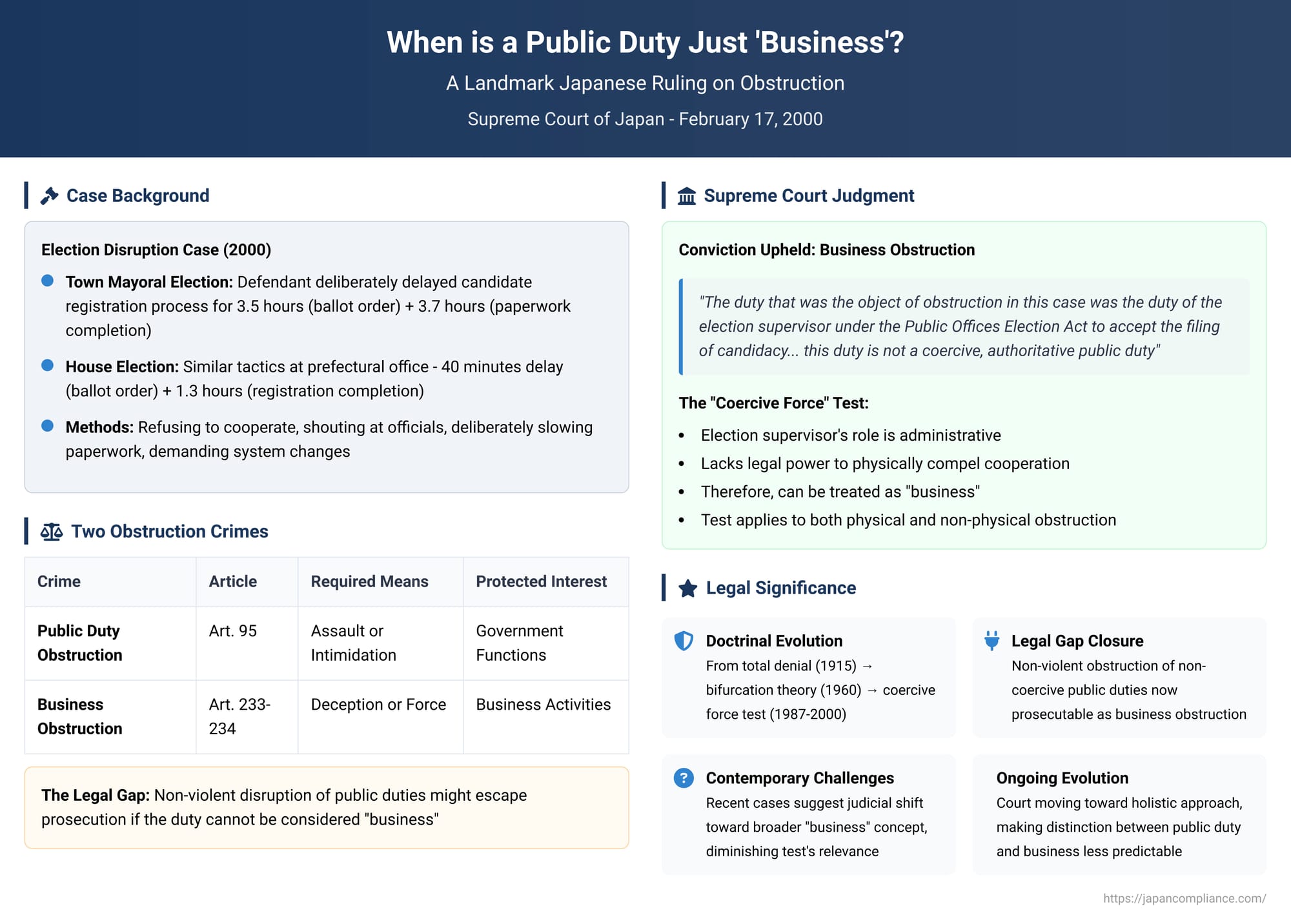

Imagine a person deliberately disrupting a government function—not with violence, but with stubborn non-cooperation, shouting, and delay tactics. Does this amount to the serious crime of "Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty," which requires assault or intimidation, or can it be prosecuted under the broader, more flexible charge of "Obstruction of Business"? This critical distinction, which addresses a potential gap in the law for non-violent obstruction of official functions, was the subject of a key ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 17, 2000.

The case, involving a defendant who systematically delayed the registration process for election candidates, solidified a crucial legal test for determining when a public duty can be treated as "business." The Court's decision confirmed that the key factor is whether the duty is "coercive" and "authoritative" in nature, providing a standard that, while clear at the time, has been the subject of ongoing judicial evolution and scholarly debate.

The Two Crimes of Obstruction: A Critical Distinction

To understand the case's significance, one must first grasp the distinction between two separate crimes in the Japanese Penal Code:

- Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty (Article 95): This crime specifically protects the execution of official government duties. Critically, it requires a high threshold for the means of obstruction: the act must involve "assault or intimidation".

- Obstruction of Business (Articles 233 & 234): This crime protects a person's "business." The means of obstruction are broader, covering acts of "deception" or "force" (iryoku). "Force" in this context is a broader concept than "assault" and can include non-violent but powerful pressure or disruption.

This difference in the required means creates a potential legal loophole. If a public duty cannot be considered "business," then disrupting it with non-violent "force" or "deception" might not be punishable under either statute. The central legal question, therefore, has long been: when can a "public duty" (kōmu) also be considered a "business" (gyōmu)?

The Facts: Delay Tactics at the Election Office

The defendant in this case engaged in a calculated campaign of disruption during the candidate registration period for two separate elections.

- Town Mayoral Election: When registering a candidate, the defendant obstructed the duties of the election supervisor for hours. He stubbornly demanded changes to the lottery system used to determine ballot order, refused to draw his lot, shouted at officials, and then, after the ballot order was finally decided, deliberately slowed down the process of filling out the required registration documents. The process of determining the ballot order was delayed by approximately 3 hours and 30 minutes, and it took another 3 hours and 40 minutes before the first candidate's registration could be accepted.

- House of Representatives Election: At the prefectural office for a different election, the defendant employed similar tactics. After drawing a lot for ballot order, he refused to tell the officials the number he had drawn or the candidate's name. He again deliberately delayed completing the paperwork and shouted at officials, causing a 40-minute delay in determining the ballot order and a delay of approximately 1 hour and 19 minutes in completing the registrations for all eight candidates present.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of obstruction of business. He appealed, arguing that he was obstructing a public duty, not a business, and his non-violent actions did not meet the "assault or intimidation" standard.

The Evolution of a Legal Doctrine

The Supreme Court's 2000 decision was the culmination of a long evolution in judicial thinking on this issue.

- Phase 1: The Old Rule (Total Denial): For much of the early 20th century, the courts, including a 1915 Great Court of Cassation ruling, held that public duties could never be considered "business," as a separate crime already existed to protect them.

- Phase 2: The Bifurcation Theory: This rigid view was overturned in a landmark 1960 Supreme Court case involving the then state-run Japan National Railways (JNR). The Court "bifurcated" public duties into two categories. It reasoned that while the JNR's transport service was technically a public duty, its actual operations were identical to those of a private railway and did not involve "authoritative or dominant" power. The Court thus created a distinction between "pure" authoritative public duties and "business-like" non-authoritative duties, holding that the latter could be protected by the obstruction of business statute.

- Phase 3: The "Coercive Force" Test: In the following decades, the courts began to refine what "authoritative" meant. The focus shifted to whether the public duty inherently possessed the power to overcome non-violent obstruction. In a pivotal 1987 decision, the Supreme Court solidified this into the "coercive force" test. It ruled that obstructing a prefectural assembly committee meeting was obstruction of business because the committee's duties were "not a coercive, authoritative public duty". A law clerk's influential commentary explained the logic: coercive duties are inherently "tougher" and are expected to withstand lesser forms of obstruction like mere "force".

The 2000 Supreme Court Ruling: Applying the Test

The Supreme Court in the 2000 election case squarely applied this "coercive force" test to the defendant's actions. The Court's reasoning was concise and direct:

"the duty that was the object of obstruction in this case was the duty of the election supervisor under the Public Offices Election Act to accept the filing of candidacy... this duty is not a coercive, authoritative public duty".

Because the election supervisor's role is administrative and lacks the legal power to physically compel a disruptive person to cooperate, it is not a "coercive" duty. Therefore, the Court concluded, this duty can be treated as "business," and the defendant's acts of deliberate delay and disruption rightfully constituted the crime of obstruction of business. The decision was significant because it confirmed that the coercive force test, previously applied in cases of physical "force," was also the correct standard for cases involving non-physical "deception" or delay tactics.

Analysis and Subsequent Challenges: Has the Test Lost Its Meaning?

While the 2000 ruling solidified the "coercive force" test as the official standard, subsequent case law has raised questions about its continued relevance and consistent application.

Legal commentary points to a 2002 Supreme Court case where obstructing the removal of homeless shelters was found to be obstruction of business, even though police were on hand and used physical force to remove protestors. The Court appeared to look past the actual use of coercion by framing the overall government project in broader, non-coercive terms like "environmental improvement".

More recently, a series of cases involving false reports to the police or other agencies has further complicated the issue. In these cases, courts have held that the obstructed "business" is the police's original, intended duty (e.g., routine patrol) that they would have been performing if they hadn't been diverted by the false report. In this line of reasoning, the question of whether the police response itself was "coercive" is sidestepped entirely.

This trend suggests a judicial shift towards viewing "public duty" as a broad, continuous activity, much like "business," which may render the "coercive force" test less determinative than it once was.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2000 decision remains a cornerstone of Japanese law on obstruction. It formally established the "coercive force" test as the standard for determining when a public duty can be protected under the broader obstruction of business statute. The principle is clear: public duties that are non-coercive and lack the inherent power to repel non-violent disruption are treated as "business," closing a potential loophole in the law.

However, the ruling must be seen within an ongoing evolution of judicial thought. While the "coercive force" test remains the official doctrine, subsequent decisions suggest a move towards a more holistic, and perhaps less predictable, approach. The fundamental legal question of what truly distinguishes a "public duty" from a "business" continues to be shaped by the courts, reflecting the ever-changing nature of the relationship between the state and the public it serves.