When Is a Palace a Single Home? The Heian Shrine Arson Case and the Law of Integrality

Imagine a vast, sprawling architectural complex—a historic palace, a university campus, or a grand temple with numerous halls, corridors, and living quarters. If a person sleeps in a gatehouse on one end of the property, and an arsonist sets fire to a distant, unoccupied library on the other, is the crime an attack on a "home"? Does the entire complex count as a single "inhabited building," triggering the law's most severe penalties, or are they separate structures?

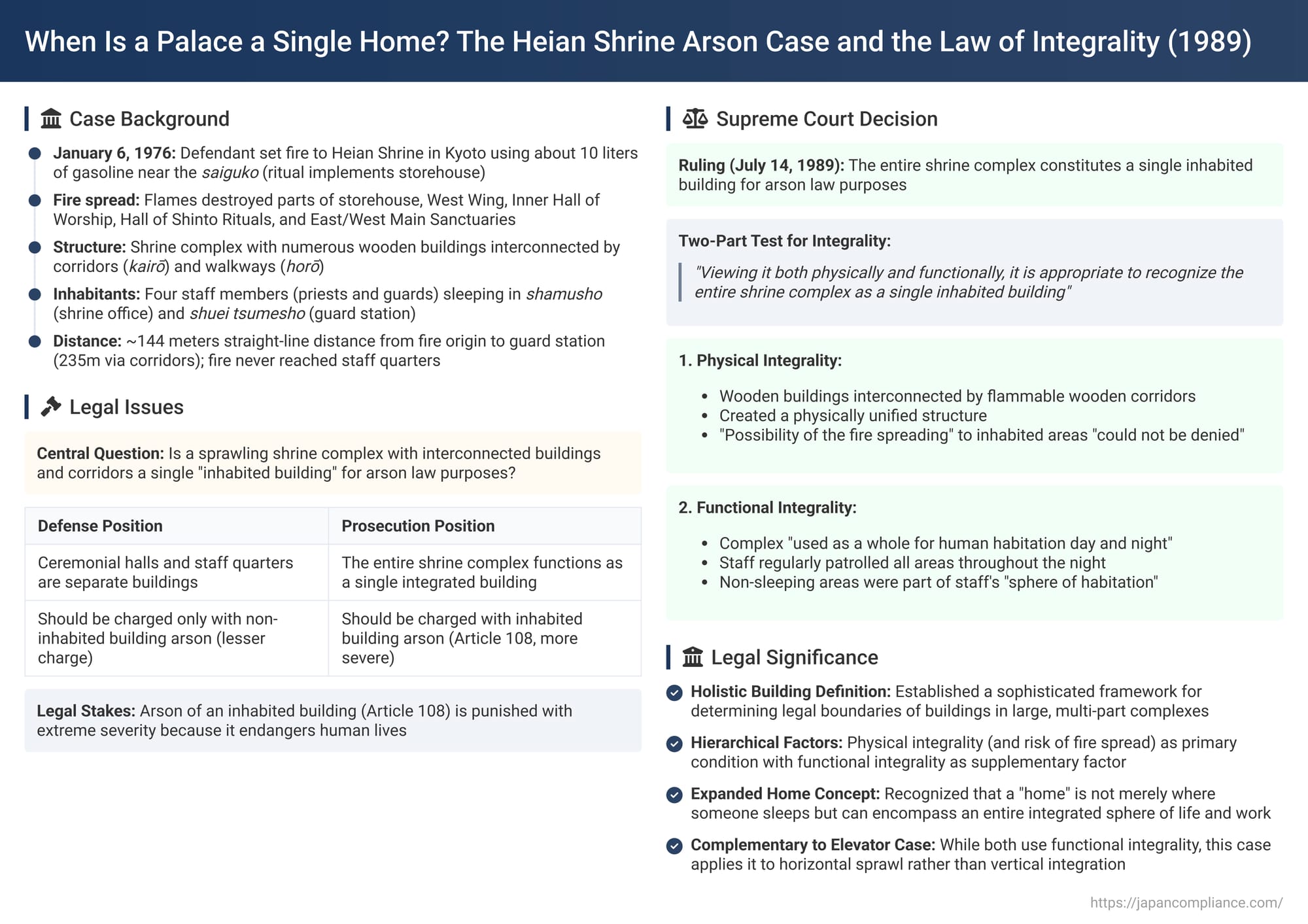

This complex question of legal and architectural boundaries was at the center of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 14, 1989. The case, involving the tragic arson of Kyoto's famous Heian Shrine, forced the Court to define the legal concept of a single building in the context of a multi-structure complex. The resulting judgment established a crucial two-part test of "integrality" that continues to guide Japanese arson law.

The Facts: The Attack on Heian Shrine

In the early morning hours of January 6, 1976, the defendant set fire to the Heian Shrine, a vast and iconic Shinto shrine in Kyoto.

- The Target: The fire was started with about 10 liters of gasoline near the saiguko, a storehouse for ritual implements. The flames subsequently spread, engulfing and destroying all or parts of the storehouse, the West Wing, the Inner Hall of Worship, the Hall of Shinto Rituals, and the East and West Main Sanctuaries.

- The Structure: The Heian Shrine is not a single edifice but a massive complex of numerous wooden buildings, including main halls, worship halls, offices, and gates. These structures are arranged in a square around a central courtyard and are interconnected by a network of long, wooden inner and outer corridors (kairō) and walkways (horō). The design allows a person to walk from one building to any other under the cover of these connecting corridors. All the buildings and corridors were made of wood.

- The Inhabitants: At the time of the fire, four staff members were on overnight duty at the shrine. Priests and a guard were sleeping in the shamusho (shrine office), while another guard was sleeping in the shuei tsumesho (guard station). These living quarters were a considerable distance from where the fire was set—for instance, the straight-line distance from the fire's origin to the guard station was about 144 meters, and the walking distance via the corridors was about 235 meters. The fire never reached the buildings where the staff were sleeping.

The defendant was charged with arson of a currently inhabited building. His defense argued that the burned ceremonial halls were separate, non-inhabited buildings from the distant staff quarters, and therefore, he should only be guilty of the lesser crime of non-inhabited building arson.

The Legal Stakes: "Inhabited" vs. "Non-Inhabited" Arson

This distinction is of paramount importance in the Japanese Penal Code.

- Arson of a currently inhabited building (Article 108) is punished with extreme severity because it is considered a crime against human life and safety, not just property.

- The definition of "inhabited" includes not only places used as a primary residence but also locations where people regularly stay overnight, such as a duty room in a shrine or office.

The Supreme Court's Two-Part Test for Integrality

The Supreme Court rejected the defense's argument and upheld the conviction for the more serious crime. In its decision, the Court established a clear, two-part framework for determining whether a complex of structures constitutes a single, integrated inhabited building. It announced that the shrine must be viewed both physically and functionally.

1. Physical Integrality

The Court first looked at the physical structure of the shrine.

- It noted that all the individual buildings were constructed of wood and were interconnected by flammable wooden corridors and walkways.

- This created a single, physically unified structure.

- Crucially, because of this interconnected wooden construction, the Court found that "the possibility of the fire spreading" from the ceremonial halls to the inhabited office and guard station "could not be denied". This risk of the fire spreading throughout the entire complex was a key element in viewing it as a single physical entity.

2. Functional Integrality

Next, the Court examined how the entire complex was used.

- It found that the shrine was "used as a whole for human habitation day and night".

- The evidence for this was the routine of the overnight staff. The priests and guards did not merely remain in their sleeping quarters; their duties involved patrolling the shrine grounds and buildings (with the exception of the main sanctuaries) throughout the night.

- This constant use and monitoring of the entire complex made the non-sleeping areas part of their "sphere of habitation," functionally uniting the distant parts of the shrine into a single operational whole.

Based on these two pillars, the Court concluded: "Viewing it both physically and functionally, it is appropriate to recognize the entire shrine complex as a single inhabited building".

Analysis: A Holistic Approach to Defining a "Dwelling"

This decision is significant for creating a holistic test that moves beyond a simplistic view of separate walls and roofs. The relationship between the two factors is a subject of legal debate.

- While one could view them as parallel criteria, the majority academic view holds that they are hierarchical.

- Physical integrality (and the resulting risk of fire spread) is seen as the primary, necessary condition.

- Functional integrality serves as a powerful supplementary factor, especially in cases like this where the physical connection is tenuous due to the large distances involved. The risk of the fire spreading over 144 meters of open-air corridors was arguably weaker than in a compact building. Therefore, the strong evidence of functional unity—the nightly patrols that put the staff in proximity to all parts of the complex—was used to bolster the conclusion that the entire complex was one entity where the inhabitants' lives were at risk.

The concept of functional integrality has been criticized by some scholars for being potentially vague and leading to an over-expansion of criminal liability. It is therefore applied with caution. The prevailing view is that it should generally only be considered when a structural connection already exists, as it did in this case with the corridors. It would likely not be used to join two completely separate, unconnected buildings on the same property into a single inhabited structure, even if they were used together. This case should also be distinguished from the "elevator arson" case, where functional integrality was key but within a single, vertical, and clearly unified structure.

Conclusion

The 1989 Heian Shrine arson decision remains the leading authority in Japan for determining the legal boundaries of an inhabited building in large, multi-part complexes. It established a sophisticated framework that requires courts to assess both the physical risk of a fire's spread and the functional reality of how a space is used. The ruling powerfully demonstrates that, for the purposes of the law's most serious protections, a "home" is not merely the room where a person sleeps. It can encompass an entire integrated sphere of life, work, and duty—a sphere where any fire, no matter how distant its origin, poses a threat to the safety of those within.