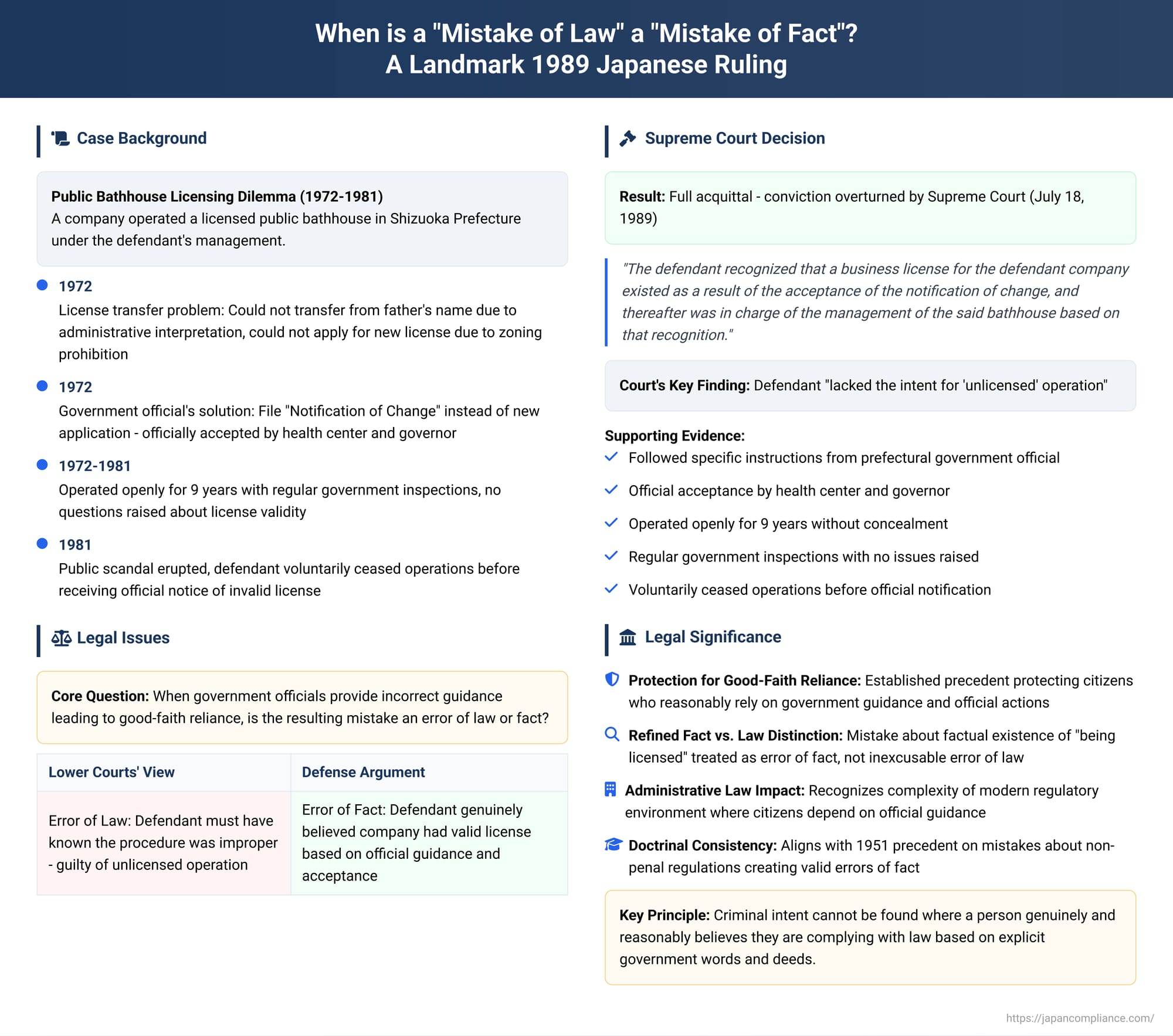

When is a "Mistake of Law" a "Mistake of Fact"? A Landmark 1989 Japanese Ruling

Decision Date: July 18, 1989

It is a foundational tenet of criminal law that ignorance of the law is no excuse. A person cannot escape conviction by claiming they were unaware their conduct was illegal. This is known as an "error of law." In contrast, an "error of fact"—a mistake about a factual circumstance of the crime—can negate the necessary criminal intent. But in the complex world of business regulation, where actions are governed by a labyrinth of permits, licenses, and administrative guidance, the line between these two types of mistakes can become profoundly blurred.

What happens when a business owner, after consulting with government officials, follows their explicit instructions and is led to believe they have a valid permit to operate, only to find out years later that the officials were wrong and the permit is legally void? Is their mistake an inexcusable error of law, or is it a legally valid error of fact? On July 18, 1989, the Supreme Court of Japan tackled this very question, issuing a landmark decision that resulted in the full acquittal of a business owner who had operated for years under just such a good-faith mistake.

The Factual Background: A Regulatory Maze and a Catch-22

The case centered on a company, represented by the defendant, that operated a special type of public bathhouse in Shizuoka Prefecture. The business itself had a valid license, but it was under the name of the defendant's elderly and ailing father, B.

The Problem:

In 1972, with his father's health failing, the defendant sought to have the business license formally transferred to his company's name. He immediately ran into a regulatory Catch-22.

- According to the established administrative interpretation of the Public Bathhouse Act, a license could not simply be transferred. The defendant's company would have to apply for a completely new license.

- However, a recent change to local zoning laws had prohibited the opening of new bathhouses of that specific type in the area where the business was located. A new application was therefore doomed to fail.

- The only saving grace was a grandfather clause, which allowed businesses that were already licensed before the zoning change to continue operating.

The defendant was stuck. He could not legally transfer the old license, and he could not legally obtain a new one.

The "Solution" Offered by Officials:

Seeking a way out of this impasse, the defendant, through a prefectural assembly member, C, petitioned the prefectural health department. An official at the department, D, gave him specific instructions. He told the defendant not to file for a new license, but to instead submit a form called a "Notification of Change in Licensed Matters" (henkō todoke) to simply change the name of the license holder from his father, B, to his company.

Official Acceptance and Years of Operation:

The defendant meticulously followed these instructions. He prepared the "Notification of Change" as directed and submitted it to the local health center. The health center officially accepted the document, forwarded it to the Governor of Shizuoka Prefecture, who also formally accepted it. As a result, the official public bathhouse registry was amended to list the defendant's company as the licensee.

For the next nine years, from 1972 until 1981, the defendant operated the bathhouse openly under his company's name. He never attempted to conceal the company's ownership. During this entire period, the local health center conducted regular, periodic inspections of the facility and never once raised any issue with the validity of the company's license.

The Unraveling:

The issue exploded into a public scandal in March 1981, when the legality of the "name change" was questioned in the Shizuoka city assembly and reported in the local newspapers. Shortly thereafter, the defendant voluntarily ceased operations. It was only after he had already closed the business that he received an official notice from the governor stating that the 1972 acceptance of his "Notification of Change" was legally invalid and that he had, in fact, been operating without a license for nearly a decade.

He and his company were subsequently charged with violating the Public Bathhouse Act for operating without a license.

The Lower Courts' Ruling: A Finding of Guilt

Both the trial court and the High Court found the defendant guilty. Their reasoning was that the government's 1972 acceptance of the "Notification of Change" was a clear and significant administrative error that rendered the act legally void from the beginning. Crucially, they found that the defendant, as a business operator, must have known that this procedure was not the proper way to obtain a license and that his company was therefore operating without a valid permit. They concluded that he possessed the necessary criminal intent.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Acquittal

In a remarkable reversal, the Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions and issued a full acquittal.

The Court cleverly sidestepped the thorny administrative law question of whether the government's acceptance of the form was legally valid. It stated, "setting aside the question of whether it can be said that a business license for the defendant company existed...," and chose instead to focus entirely on the defendant's subjective state of mind.

The Court found that it was "clear" that the defendant:

"...recognized that a business license for the defendant company existed as a result of the acceptance of the notification of change, and thereafter was in charge of the management of the said bathhouse based on that recognition."

To support this finding, the Court highlighted a compelling list of facts:

- The defendant had acted on the specific instructions of a prefectural government official on how to prepare and file the necessary paperwork.

- He had been told by officials, including the director of the local health center, that the government intended to accept his filing.

- He operated his business openly for nine years, never once concealing that the company was the operator.

- He was subjected to regular government inspections for nine years, during which no regulatory body ever questioned the validity of his license.

- He voluntarily ceased operations before he was even officially notified that his license was considered invalid.

Based on this overwhelming evidence of good faith, the Supreme Court concluded that the defendant "lacked the intent for 'unlicensed' operation," and therefore, the crime of operating without a license was not established.

A Deeper Dive: Fact vs. Law in a Regulatory World

This case is a masterclass in the crucial, and often difficult, distinction between an error of fact and an error of law.

- The Argument for Error of Law: The lower courts and some legal critics argued that the defendant's mistake was a legal one. He knew all the physical facts—he knew he had filed a "notification of change" and not a "new application." His mistake was in misinterpreting the legal effect of that action. Under the traditional view that ignorance of the law is no excuse, he should be guilty.

- The Argument for Error of Fact (The Court's View): The Supreme Court implicitly treated the defendant's mistake as an error of fact. The crime is "unlicensed operation." The key factual element is the absence of a "license." The defendant's mistake was not about the law prohibiting unlicensed operation (he knew a license was required), but about the factual existence of a valid license for his company. He genuinely and reasonably believed, based on the government's own official actions and assurances, that the factual state of "being licensed" existed.

This approach aligns with other key precedents, such as a famous 1951 case involving a man who killed a dog, mistakenly believing a local ordinance made all unlicensed dogs legally "ownerless." In that case, too, the Supreme Court found that a misunderstanding of a non-penal regulation could lead to a valid error of fact about a core element of a crime (the "ownership" of the dog). The 1989 bathhouse ruling is a powerful modern affirmation of this principle.

Conclusion: Protecting Good-Faith Reliance on Government

The 1989 Public Bathhouse case is a landmark decision that provides vital protection for citizens and businesses who act in good-faith reliance on the guidance and official actions of their government. It establishes the critical principle that a mistake about one's legal status (e.g., "being licensed"), when based on a reasonable interpretation of official instructions and actions, will be treated as a legally exculpatory error of fact, not an inexcusable error of law.

The Supreme Court’s decision represents a pragmatic and just approach to a complex problem. It recognizes that in the dense thicket of modern administrative law, citizens should not be held criminally liable for mistakes that were induced by the very government officials tasked with providing clarity. It affirms that criminal intent cannot be found where a person genuinely and reasonably believes they are complying with the law, based on the explicit words and deeds of the state itself.