When is a Bad Loan a Crime? A Japanese Ruling on Breach of Trust and the Business Judgment Rule

Imagine a bank's top executives are faced with a difficult decision. A major corporate borrower is on the verge of collapse. If the borrower fails, the bank will suffer massive losses on its existing loans. To stave off disaster, the executives decide to approve a series of risky, new, unsecured loans, hoping to keep the client afloat long enough to engineer a workout and minimize the bank's ultimate losses. When this gamble fails and the bank itself is pushed toward insolvency, are the executives merely guilty of poor business strategy, or have they committed the serious crime of "special breach of trust"?

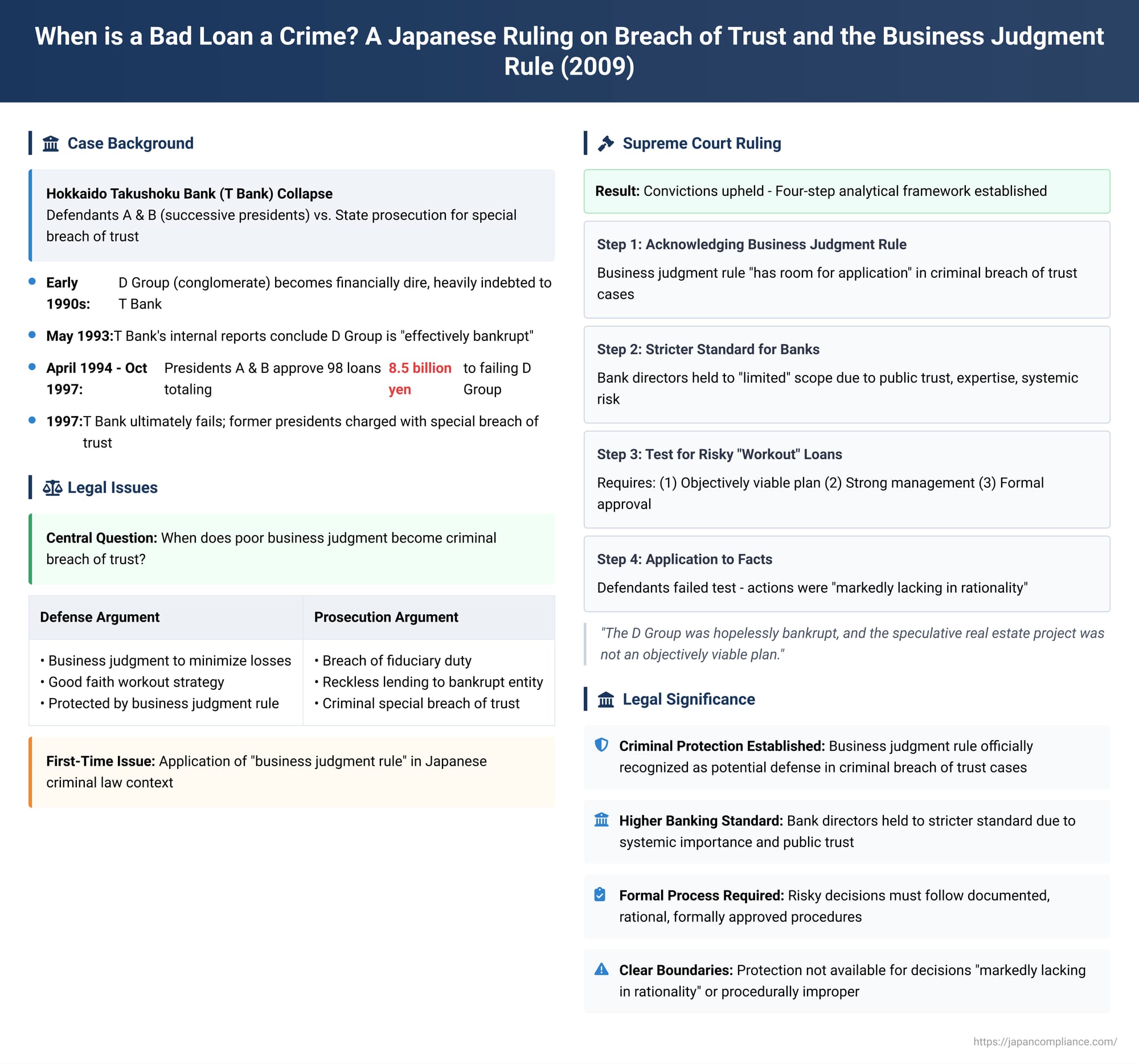

This high-stakes scenario, which tests the line between aggressive business judgment and criminal misconduct, was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 9, 2009. The case, arising from the spectacular collapse of the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank (T Bank), one of Japan's most infamous corporate failures, forced the Court to address for the first time how the "business judgment rule" applies in a criminal context. The ruling provides a crucial framework for understanding the duties and potential criminal liability of corporate directors in Japan.

The Facts: The Bank and the Bankrupt Conglomerate

The defendants, A and B, were successive presidents of T Bank. For years, the bank had been the primary financial backer of a sprawling conglomerate known as the D Group, run by defendant C. The D Group, which operated businesses ranging from beauty salons to luxury hotels and leisure facilities, was a key part of T Bank's strategy to support emerging companies.

By the early 1990s, however, the D Group's financial situation had become dire. The businesses were losing massive amounts of money, and the group was saddled with enormous debt, most of it owed to T Bank and its affiliates. By May 1993, T Bank's own internal reports concluded that the D Group was effectively bankrupt, able to continue operating only because of a constant infusion of new loans from T Bank to cover its staggering losses. The group's only hope for repayment was a highly speculative and legally fraught real estate project that had little chance of success.

Despite being fully aware of this catastrophic situation, defendants A and B, during their respective terms as president, continued to approve a relentless series of additional, essentially unsecured loans to the D Group. Between April 1994 and October 1997, they authorized 98 separate loans totaling over 8.5 billion yen. These funds were not for new investments but were "loss-covering funds" intended merely to keep the D Group from collapsing and forcing T Bank to acknowledge its monumental losses.

When T Bank ultimately failed, the former presidents were charged with special breach of trust. Their defense was that they were not acting disloyally. They argued their actions were a difficult but necessary business judgment, aimed at minimizing the bank's total losses by preventing an immediate and disorderly bankruptcy of a major client.

The Legal Framework: Breach of Trust and the Business Judgment Rule

The defendants were charged under Japan's "special breach of trust" statute (tokubetsu hainin-zai), a provision of the Commercial Code (now the Companies Act) that applies specifically to corporate directors. The crime requires that a director, acting for an improper purpose, breaches their duties and causes financial damage to the company.

The central question in the case was whether the defendants' decision to continue lending to a company they knew was bankrupt was a "breach of duty." The defense argued that their actions should be protected by the "business judgment rule" (keiei handan no gensoku). This legal principle, originating in U.S. corporate law, generally holds that courts should not second-guess the business decisions of directors with the benefit of hindsight. As long as a decision is made in good faith and with due care, directors are typically shielded from liability even if the decision turns out badly. This case was the first time the Japanese Supreme Court had to consider the rule's application in a criminal trial.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Higher Duty for Bankers

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions of the bank presidents, but its reasoning was a masterclass in legal nuance. It provided a definitive framework for how the business judgment rule applies to corporate directors, especially those in the banking sector.

Step 1: Acknowledging the Business Judgment Rule

In a statement of major significance for the business world, the Court declared for the first time that the business judgment rule "has room for application" in criminal breach of trust cases. This was a landmark acknowledgment, providing a potential shield for directors against criminal charges arising from good-faith, albeit unsuccessful, business decisions.

Step 2: A Stricter Standard for Banks

The Court immediately followed this with a crucial qualification. It held that the scope for applying the rule to bank directors is "limited" compared to directors of ordinary companies. The Court gave several reasons for this higher standard: banking is a licensed business that operates using public deposits as its capital; bank directors are financial experts expected to use their specialized knowledge responsibly; and the failure of a bank can cause "widespread and grave confusion for society in general."

Step 3: The Test for Risky "Workout" Loans

The Court then laid out the specific, strict conditions that must be met for a risky loan to a failing company to be considered a valid and defensible business judgment. It acknowledged that providing additional financing to an insolvent company could, in exceptional cases, be a legitimate strategy to facilitate a restructuring and maximize recovery. However, for this exception to apply, the Court required:

- An "objectively viable reconstruction or workout plan."

- A "strong management constitution" within the bank, capable of executing such a complex plan.

- A formal decision-making process based on a "clear internal plan" that has received "formal approval."

Step 4: Application to the Facts

The Supreme Court found that the defendants' actions failed this test completely. The D Group was hopelessly bankrupt, and the speculative real estate project was not an objectively viable plan. The defendants had not drafted or followed any clear, formally approved workout strategy. Their lending was an ad-hoc series of cash infusions to delay the inevitable. The Court therefore concluded that their lending decisions were "markedly lacking in rationality" and a clear breach of their fundamental duty to protect the bank's assets. As one of the justices noted in a supplementary opinion, the defendants had so clearly failed in their basic duties that it was hardly necessary to even discuss the business judgment rule.

Conclusion: Defining the Boundaries of Executive Responsibility

The 2009 Supreme Court decision in the T Bank case is the most important modern ruling on the criminal liability of corporate directors in Japan. It provides a sophisticated, fact-intensive framework for assessing breach of trust, balancing the need to allow executives to take calculated business risks against the duty to hold them accountable for disloyalty and recklessness.

The ruling establishes two vital principles:

- The business judgment rule is now officially recognized as a potential defense in criminal breach of trust cases in Japan, a significant development for corporate governance.

- However, this protection is not a blank check. Directors, particularly those in systemically important industries like banking, are held to a higher standard of care.

A risky decision to support a failing enterprise will only be protected if it is part of a formal, documented, and objectively rational plan for reconstruction or loss minimization. The decision sends a clear warning to corporate leaders that while the law respects the difficulty of business judgment, it will not protect decisions that are reckless, procedurally improper, or, as the Court found here, "markedly lacking in rationality."