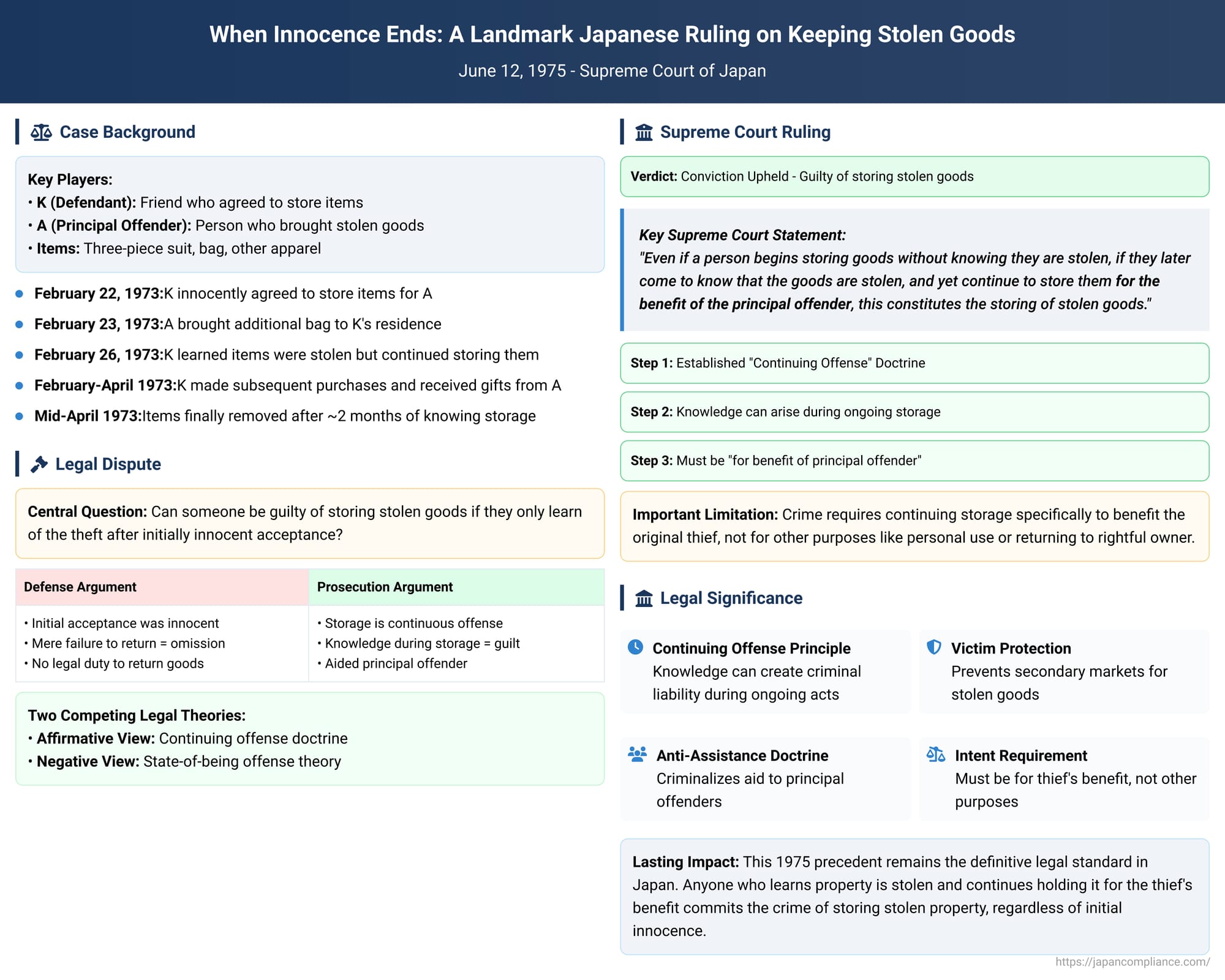

When Innocence Ends: A Landmark Japanese Ruling on Keeping Stolen Goods

What would you do if you agreed to hold a package for a friend, only to discover later that its contents were stolen? Does your continued possession, born of an innocent agreement, transform you into a criminal? This complex question sits at the heart of a pivotal June 12, 1975, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan, a ruling that continues to shape the country's understanding of criminal liability for handling stolen property.

The case, officially known as the "Case Concerning the Crimes of Storing, Buying, and Receiving Stolen Goods," delves into the murky territory of when knowledge acquired midway through an act can retroactively imbue that act with criminal intent. It forces a confrontation between two fundamental legal concepts: Is the crime a single act of acceptance, or is it a continuous state of possession? The answer has profound implications for understanding the nature of criminal responsibility.

A Favor for a Friend: The Factual Background

The story begins in February 1973 in Osaka. A man, whom we will call K, agreed to look after some items for his acquaintance, A. On the evening of February 22, A brought a three-piece suit and other apparel to K’s residence. K accepted the items for safekeeping. The next day, A brought over a bag, which K also agreed to store. At this point, K had no reason to believe anything was amiss.

The situation changed dramatically a few days later, on February 26. K learned from A that the suit, the bag, and the other items were not legitimately A's property; they were, in fact, stolen. Despite this revelation, K did nothing. The stolen goods remained in his room. He neither returned them to A, nor did he report the matter to the police. He simply continued to hold them, day after day, until mid-April—a period of nearly two months after he learned the truth.

K's involvement did not end there. In the weeks following his discovery, he entered into a series of further transactions with A, all while fully aware that he was dealing in stolen property. On multiple occasions, he purchased items like cameras, tape recorders, and kimonos from A. He also accepted gifts from A, including a necklace and other valuables. In one instance, he even agreed to store another stolen item, a suit jacket.

The Journey Through the Courts

The Osaka District Court, the court of first instance, found K guilty on all counts. It convicted him of:

- Storing stolen goods (an offense known then as zōbutsu kizō, now tōhin-tō hokan), for continuing to keep the initial set of items after learning they were stolen.

- Buying stolen goods (zōbutsu kōbai, now tōhin-tō yūshō yuzuriuke), for the subsequent purchases.

- Receiving stolen goods (zōbutsu shujū, now tōhin-tō mushō yuzuriuke), for accepting the gifts.

- A second count of storing stolen goods, for the final suit jacket he agreed to hold.

K appealed the decision to the Osaka High Court, focusing his argument on the first conviction. He argued that the crime of "storing" stolen goods could not be established if he was unaware of their illicit nature at the moment he initially took possession. He contended that merely learning the truth later and failing to act was not enough to constitute a crime. His act of acceptance was innocent; how could his passive inaction thereafter be criminal?

The High Court disagreed. In its judgment, the court reasoned that there was no substantive difference between someone who knowingly accepts stolen goods from the outset and someone who, after innocently accepting them, learns the truth and chooses to continue holding them. The court laid out a crucial exception: the crime would not be established if it were impossible for the person to return the goods, or if they had a legal right to retain them (such as a lien).

However, in K's case, he had no such right, and returning the items was perfectly feasible. The court found K's criminal intent to be "obvious." It pointed to his subsequent actions—repeatedly buying, receiving, and storing more stolen goods from the same individual—as clear evidence that he fully intended to continue his custodianship of the initial items for A's benefit. The appeal was dismissed.

Undeterred, K took his case to the Supreme Court of Japan. His defense lawyer articulated a more refined legal argument. He characterized the act of "storing" (kizō) as a hybrid of action and inaction. The "acceptance" and "return" of goods are active commissions, but the "keeping" or "holding" in between is a passive omission. Once the goods are received, the lawyer argued, no further action is required until they are returned. Therefore, simply learning that the goods were stolen does not automatically create a legal duty to return them. Without a subsequent, positive act—such as moving the items to a new hiding place—the mere failure to return them (an omission) could not be punished as the crime of "storing."

The Supreme Court's Concise but Powerful Ruling

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal. In a brief but momentous ex officio statement—a judgment made on the court's own authority to address a key point of law—it set a binding precedent. The Court declared:

"Even if a person begins storing goods without knowing they are stolen, if they later come to know that the goods are stolen, and yet continue to store them for the benefit of the principal offender, this constitutes the storing of stolen goods."

The Court found no legal error in the High Court's decision and finalized the conviction. With this single sentence, the Supreme Court provided a definitive answer to the central question, establishing a legal principle that has guided Japanese criminal law ever since.

Unpacking the Decision: A Clash of Legal Theories

The Supreme Court's ruling, while succinct, is the culmination of a deep and ongoing debate in Japanese criminal law. It represents the triumph of one major legal theory over another. To fully grasp its significance, we must explore these competing viewpoints.

The Affirmative View: The "Continuing Offense" Doctrine

The Supreme Court's decision is the classic expression of what is known as the "affirmative view," which was already the prevailing theory among scholars at the time. This view posits that the crime of storing stolen goods can be established even if the defendant only becomes aware of the property's illicit nature after taking possession. The legal reasoning behind this is twofold.

First, the crime of storing stolen property is classified as a "continuing offense" (keizokuhan). Unlike an "instantaneous offense" (jōtaihan or shunkanhan), which is complete the moment the criminal act occurs (like a single punch in an assault), a continuing offense involves a criminal state that persists over a period. The classic example is unlawful confinement; the crime is not just the act of locking the door, but the entire period during which the victim remains imprisoned.

Applying this logic, the act of "storing" is not merely the initial acceptance of the goods. It is the entire, uninterrupted act of keeping them in one's custody. The crime is ongoing as long as the state of storage continues. Consequently, if the requisite criminal intent (the knowledge that the goods are stolen) arises at any point during this continuous act, the crime is perfected from that moment forward. K's crime did not begin on February 22 when he innocently accepted the suit, but on February 26, the moment he gained knowledge and his continued "storing" became a criminal act.

Second, this interpretation aligns with the protected legal interests (hogo hōeki) that the law against handling stolen goods aims to safeguard. This area of law serves two primary purposes:

- Protecting the victim's right of recovery: The law seeks to prevent a secondary market for stolen goods from flourishing, thereby making it easier for the original victim to trace and recover their property. When someone knowingly holds stolen items, they create a new obstacle to this recovery.

- Preventing aid to the principal offender: The law acts as a deterrent to post-crime assistance. By making it illegal to store, transport, or buy stolen goods, the law makes it harder for the original thief (the "principal offender") to profit from their crime and evade capture. Knowingly holding stolen goods for the thief directly assists them in securing the fruits of their crime.

From this perspective, K's actions after February 26 clearly undermined both legal interests. His continued possession made it harder for the victim to find their property and directly aided A by safeguarding the stolen items. Whether K knew the truth at the moment of acceptance is irrelevant; the harm caused by his continued knowing possession is the same.

It is crucial to note the Supreme Court's qualifying phrase: "for the benefit of the principal offender." This is a vital limitation. The crime is not established if the person continues possession for other reasons. For instance, if K, upon learning the truth, decided to keep the suit for himself (an intent known as fuhō ryōtoku no ishi), he might be guilty of a different crime like embezzlement, but not storing stolen goods. Similarly, if he was holding the items with the intention of turning them over to the police or returning them to the rightful owner, he would lack the requisite intent to aid the thief. The High Court astutely used K’s subsequent transactions with A as objective proof that his storage was, indeed, "for the benefit" of A.

The Negative View: The "State-of-Being Offense" Counterargument

Despite the Supreme Court's definitive ruling, a powerful counterargument, known as the "negative view," exists and remains influential in academic circles. This view asserts that the crime of storing stolen goods cannot be established unless the defendant knew the goods were stolen at the very moment they acquired possession.

This argument rests on a different characterization of the crime. Proponents of the negative view classify the offense not as a continuing offense, but as a "state-of-being offense" (jōtaihan). In this model, the legally significant act is the establishment of a criminal state. The core of the crime is the act of "entrustment" or "acceptance" (kitaku) which transfers possession. Once this act is complete, the crime is fully constituted. The subsequent period of holding the item is merely the maintenance of the illegal state created by the initial act; it is not, in itself, a continuous execution of the crime.

Under this theory, the defendant's mental state is only relevant at the moment of the legally proscribed act—the acquisition of possession. If K did not know the goods were stolen when he accepted them, the act itself was not criminal. The crime of storing stolen goods simply never occurred.

This leads to the second pillar of the negative view: the distinction between commission (sakui) and omission (fusakui). K's defense lawyer argued that after the initial acceptance (a commission), his failure to return the items was merely an omission. In criminal law, punishing an omission is generally more difficult than punishing a commission. It typically requires the existence of a specific legal duty to act. For example, a parent has a duty to feed their child, and a failure to do so can be criminal.

The negative view asks: what legal duty did K have to return the goods or report the crime? While one might argue a moral duty exists, proponents of this view are reluctant to have the criminal law impose such a broad, general duty on citizens to correct situations they did not criminally create. Without a clear statutory duty to act, punishing K's passive failure to return the items is seen as an overextension of criminal liability.

Finally, this view seeks consistency with related offenses. The crimes of buying (kōbai) or receiving (juju) stolen goods indisputably require knowledge at the time of the transaction. You cannot be guilty of buying stolen goods if you only find out they were stolen a week after the purchase. Proponents of the negative view argue that it is inconsistent to treat "storing" differently. All these offenses are part of the same statutory chapter and serve similar goals. They should, therefore, require the same temporal link between the act and the intent: knowledge must exist at the moment one takes possession.

Conclusion: A Lasting Precedent

The 1975 Supreme Court decision remains the definitive legal precedent on this issue in Japan. In practice and in subsequent case law, the "affirmative view" is firmly entrenched. Anyone who learns that property in their possession is stolen and knowingly continues to hold it for the thief's benefit is committing the crime of storing stolen property.

However, the academic debate endures because it touches upon fundamental questions of criminal law theory. The controversy highlights the critical distinction between continuing and instantaneous offenses—a distinction that determines the entire timeframe during which a crime can be committed. It also probes the delicate boundary between a punishable active commission and a non-punishable passive omission.

This landmark case serves as a powerful illustration of how the acquisition of knowledge can fundamentally alter the legal character of an ongoing action. An act that begins in innocence can, through the introduction of new information and the choice to persist, descend into criminality. It reminds us that in the eyes of the law, responsibility can arise not just from what we do, but from what we continue to do once we know the truth.