When Formality Clashes with Fairness: Promoters' Property Deals and Good Faith in Japanese Corporate Law

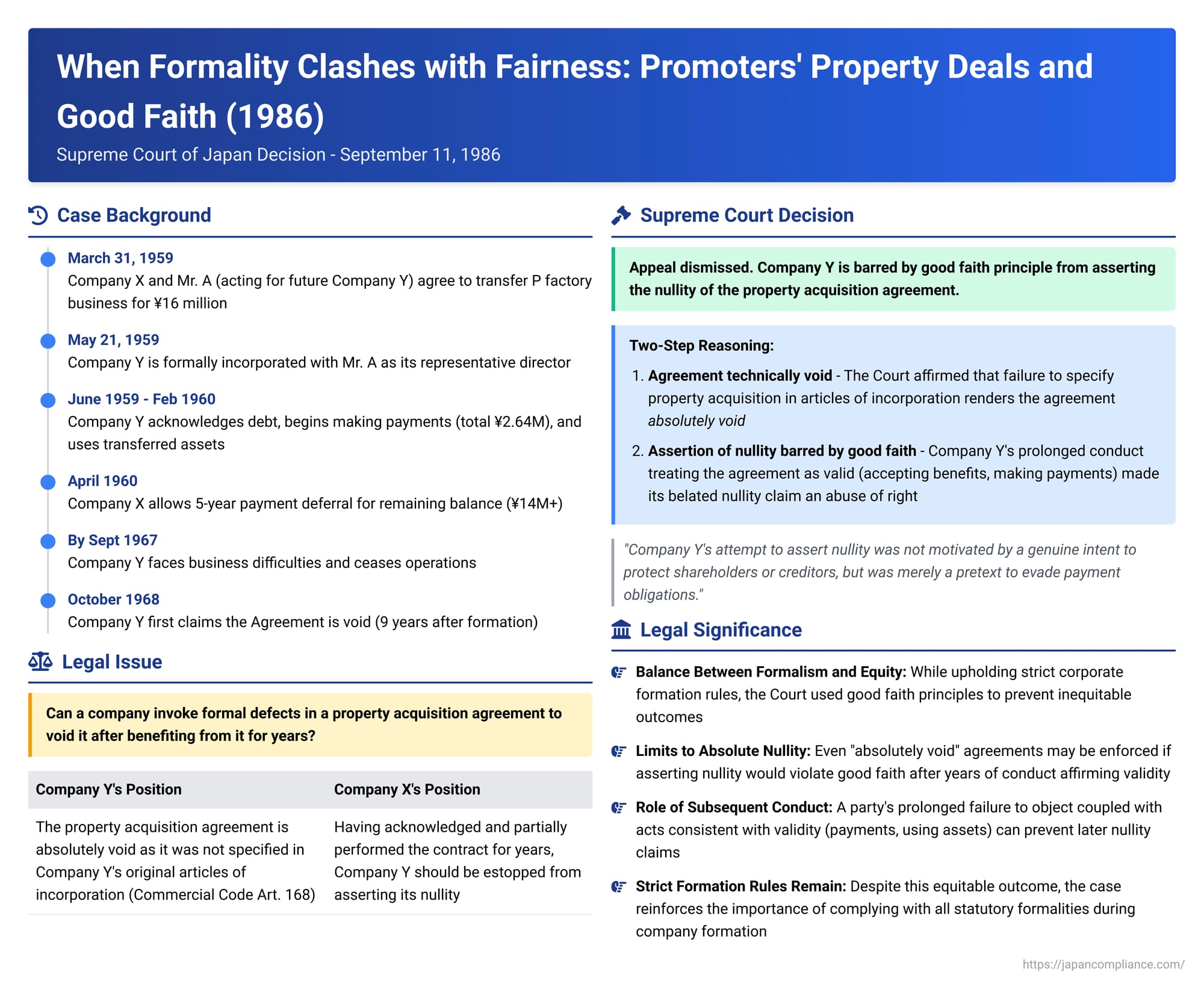

The process of establishing a new company involves numerous steps, and Japanese company law imposes strict formalities on certain pre-incorporation transactions, particularly those where promoters arrange for the company-to-be to acquire specific property. These rules, designed to protect the nascent company's capital and its future stakeholders, can render non-compliant agreements void. However, what happens when a company, having benefited from such a technically void agreement for years, later tries to use the formal defect to escape its obligations? A Japanese Supreme Court decision on September 11, 1986, grappled with this very issue, ultimately invoking the principle of good faith to prevent an inequitable outcome.

The Facts: A Factory Transfer and a Delayed Dispute

The case involved Company X, a manufacturer of tobacco machinery and small diesel engines. Company X operated three factories, one of which, the P factory, was dedicated to producing small diesel engines. Seeking to divest this part of its business, Company X approached Mr. A, encouraging him to establish a new company that would acquire the P factory's operations.

On March 31, 1959, an agreement (referred to as "the Agreement") was concluded between Company X and Mr. A, who was acting as the representative of the promoters for the new company (which would become Company Y). The key terms of the Agreement were:

- Company X would transfer the entire business of its P factory to Mr. A (acting for the new company). This included assets such as products, raw materials, accounts receivable, goodwill, and the transfer of employees and customer relationships, although the land, buildings, and machinery were to be leased separately.

- The purchase price for the business assets was set at 16 million yen, payable in installments every three months, commencing from September 1959.

- It was stipulated that once the new company was established, it would assume all of Mr. A's rights and obligations arising from the Agreement.

Subsequently, on May 21, 1959, Company Y was formally incorporated and registered, with Mr. A as its representative director. Company Y duly took possession of all the assets specified in the Agreement and commenced operations, effectively succeeding to the business of P factory.

A critical legal issue arose because this transaction—the pre-incorporation agreement for Company Y to acquire the P factory's business assets—was not mentioned in Company Y's original articles of incorporation. Under the Japanese Commercial Code then in effect (Article 168, Paragraph 1, Item (vi), the precursor to current Companies Act Article 28, Item 2), such an arrangement, termed "property acquisition" (zaisan hikiuke), required specific disclosure in the company's foundational articles. Mr. A, who substantially owned all of Company Y's shares and managed its establishment and initial operations, had apparently failed to ensure this due to ignorance of the specific regulatory requirement, rather than any deliberate attempt to circumvent it or because of any opposition.

For a considerable period after its incorporation, Company Y raised no objections whatsoever regarding the validity or terms of the Agreement. In fact:

- In June 1959, Company Y formally acknowledged its debt of 16 million yen to Company X under the Agreement and entered into a separate contract for its installment repayment.

- From October 1959 to February 1960, Company Y made several installment payments to Company X, totaling 2.64 million yen.

- Company Y utilized the transferred assets, sold products made from the acquired raw materials, collected receivables, and continued the business using the P factory's infrastructure.

- In April 1960, Company X, accommodating Company Y's financial situation, agreed to a five-year deferral for the payment of the outstanding balance (then over 14 million yen) and allowed for further revised installment payments.

However, Company Y later encountered significant business difficulties, including internal management disputes and the mass resignation of employees. By around September 1967, it had effectively ceased its business operations.

It was only in October 1968, during the fourth oral hearing in the first instance court proceedings initiated by Company X to recover the unpaid balance, that Company Y first formally asserted that the original Agreement was void. The basis for this claim was the failure to specify the property acquisition in its original articles of incorporation. This was roughly nine years after the Agreement was made and Company Y had begun operations.

The Legal Conundrum: Void Agreement vs. Subsequent Conduct

The lower courts, both the first instance court and the appellate court, ruled in favor of Company X, ordering Company Y to pay the outstanding amount (though the first instance court made a slight reduction). Company Y appealed to the Supreme Court, insisting on the nullity of the Agreement due to the formal defect. This presented the Supreme Court with a classic dilemma: should a contract that is technically void under strict statutory formation rules be unenforceable, even when one party has fully performed, and the other has accepted the benefits and acted consistently with the contract's validity for many years?

The Supreme Court's Two-Step Reasoning

The Supreme Court, in its First Petty Bench judgment, dismissed Company Y's appeal. Its decision meticulously navigated the tension between the strictness of corporate law formalities and the overarching principles of fairness and good faith.

Step 1: Affirming the "Absolute Nullity" of Non-Compliant Zaisan Hikiuke

The Court first addressed the nature of the Agreement and the legal consequences of its non-inclusion in Company Y's articles of incorporation.

- Characterization as Zaisan Hikiuke: The Court found that the Agreement, considering its "substantive purpose and content," was indeed a contract whereby Mr. A, acting as the representative of the promoters of Company Y, arranged for the company-in-formation to acquire the business assets of P factory, conditional upon Company Y's successful establishment. This, the Court held, fell squarely within the definition of "property acquisition" (zaisan hikiuke) as contemplated by the then-Commercial Code Article 168, Paragraph 1, Item (vi).

- Consequence of Non-Compliance – Absolute Nullity: The Court then affirmed the established legal principle that if such a zaisan hikiuke is not specified in the company's original articles of incorporation, the agreement is void. Crucially, it described this nullity as absolute. This means:

- The agreement is void in relation to everyone (erga omnes).

- The purpose of this strict rule is to broadly protect the interests of the company's stakeholders, including its shareholders and creditors, from potentially detrimental pre-incorporation deals, particularly those involving overvalued assets.

- This nullity cannot be cured by subsequent ratification by the company after its incorporation.

- Even if the company partially performs its obligations under the void agreement (like Company Y making partial payments) or utilizes the acquired assets (as Company Y did), these actions do not validate the originally void agreement.

- Company Y's Right to Assert Nullity (Generally): Therefore, the Supreme Court stated that, as a matter of principle, the Agreement was void, and Company Y, as a party to it (by assumption from Mr. A), could generally assert this nullity at any time, unless special circumstances dictated otherwise.

Step 2: Invoking the Principle of Good Faith (Shingisoku) to Bar Assertion of Nullity

Having established the Agreement's technical voidness, the Court turned to whether "special circumstances" existed that would prevent Company Y from asserting this nullity. It found that such circumstances were indeed present.

- Factual Basis for Estoppel: The Court highlighted several key facts:

- Company X had fully performed all its obligations under the Agreement by transferring the P factory business.

- Company Y had accepted this performance without any complaint for many years.

- Company Y had consistently acted on the premise that the Agreement was valid. This was evidenced by its formal acknowledgment of the debt, its partial payments of the purchase price, and its continuous use, consumption, and sale of the transferred assets (products, raw materials, etc.).

- The assertion of nullity by Company Y based on the lack of mention in the articles of incorporation came extremely late—approximately nine years after the contract was concluded and business commenced. (A separate ground for nullity, concerning Company X's alleged lack of shareholder approval for the business transfer, was raised even later, about twenty years after the contract).

- Critically, throughout this long period, neither Company Y's own shareholders, creditors, nor any other stakeholders (nor those of Company X) had ever raised any issues or concerns about the Agreement's validity based on these formal defects.

- Conclusion on Good Faith: Based on this accumulation of facts, the Supreme Court concluded that Company Y's attempt to assert the nullity of the Agreement was not motivated by a genuine intent to protect the interests of its shareholders or creditors—the very interests the statutory regulation on zaisan hikiuke was designed to safeguard. Instead, the Court found that Company Y's belated claim of nullity was merely a pretext (藉口 - shakō) to evade its responsibility to pay the outstanding balance of the purchase price, an obligation on which it was already in default.

- Violation of Good Faith Principle: Such conduct, the Court ruled, was contrary to the principle of good faith and fair dealing (信義則 - shingisoku, often referred to as Treu und Glauben or bona fides), a fundamental tenet of Japanese civil law. Asserting a formal legal defect in such a manner, solely to escape a long-acknowledged debt after benefiting from the contract, was deemed an abuse of right and impermissible.

- "Special Circumstances" Established: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that "special circumstances" did exist that estopped Company Y from asserting the nullity of the Agreement based on the violation of the zaisan hikiuke regulations.

Understanding Zaisan Hikiuke (Property Acquisition by Promoters)

The doctrine of zaisan hikiuke plays a vital role in Japanese corporate formation law.

- Definition and Purpose: It refers to an agreement made by promoters, on behalf of a company yet to be formed, to acquire specific property from a promoter or a third party once the company comes into existence. The primary purposes of subjecting such agreements to strict regulation (requiring their specification in the notarized original articles of incorporation and, generally, an independent inspector's investigation into the property's value under Companies Act Article 33) are:

- To prevent the circumvention of strict rules governing "contributions in kind" (genbutsu shusshi), where assets rather than cash are contributed for shares.

- To protect the company's initial capital base from being depleted by the acquisition of overvalued assets or by unduly burdensome obligations undertaken by promoters before the company has its own independent management. This safeguards shareholders and creditors.

The PDF commentary notes that the first rationale (preventing circumvention of rules on contributions in kind) has become less significant under modern company law, which demands actual movement of funds for cash contributions, making it harder to disguise a non-cash contribution as a cash one offset by a property purchase. The core concern today is ensuring the company doesn't start its life with an impaired capital base due to problematic pre-incorporation property deals.

- "Absolute Nullity" in Theory: The traditional and judicially affirmed consequence of failing to comply with these disclosure requirements is that the zaisan hikiuke agreement is absolutely void. This means it's void against everyone, and generally cannot be "cured" by subsequent actions like company ratification or partial performance. The Supreme Court in this case explicitly reaffirmed this "absolute nullity" principle as the starting point of its analysis.

The Principle of Good Faith (Shingisoku) as an Equitable Backstop

The principle of good faith (shingisoku) is a pervasive doctrine in Japanese civil law, akin to the principles of good faith and fair dealing, and estoppel in common law systems. It serves as an important corrective mechanism, allowing courts to prevent parties from asserting their strict legal rights in a manner that would lead to profoundly unfair or abusive outcomes.

- In this case, the Supreme Court used shingisoku to estop Company Y from relying on the formal defect (the non-disclosure of the zaisan hikiuke in its articles) to invalidate the Agreement. The Court found that Company Y's conduct over nearly a decade—acknowledging the contract, making payments, using the assets, and never raising any objection—had created a legitimate expectation on Company X's part that the Agreement was valid and would be honored. To allow Company Y to then turn around and claim nullity, especially when its business had failed for unrelated reasons, solely to avoid paying its debt, was deemed a breach of good faith.

- The Court's application of shingisoku demonstrates a balancing act: while upholding the importance of statutory formalities in corporate law, it also recognized that these formalities should not become tools for injustice or opportunism.

Discussion and Implications

The Supreme Court's decision has several important implications:

- Tension Between Formalism and Equity: It highlights the inherent tension between the strict application of formal legal rules (like those governing zaisan hikiuke) and the pursuit of equitable outcomes in individual cases. The "absolute nullity" doctrine for non-compliant zaisan hikiuke is a harsh one, reflecting the importance placed on capital integrity. However, the good faith principle provides a safety valve.

- Significance of Prolonged Inaction and Affirmative Conduct: The case underscores that a party's prolonged failure to object to a technically void agreement, coupled with actions consistent with its validity (like making payments or using assets), can be critical factors in preventing that party from later asserting nullity based on good faith.

- Scholarly Debate: The PDF commentary notes that while the outcome is generally seen as just, the legal reasoning has sparked academic discussion. Some question the logical consistency of first declaring an agreement "absolutely void" and then preventing the assertion of that very nullity based on good faith. Alternative legal constructions, such as finding an implied new contract formed after incorporation or an assumption of the contractual position by the new company from the promoter, might have been considered by some scholars to achieve a similar result without directly confronting the "absolute nullity" premise in this manner.

- Caution for Promoters and Companies: The case serves as a reminder of the critical importance of adhering to all statutory formalities during company formation, particularly concerning pre-incorporation agreements for property acquisition. Failure to do so can render such agreements void. However, it also signals that companies cannot always rely on such technical defects to escape long-standing obligations if their subsequent conduct has been inconsistent with such a claim of nullity.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's September 11, 1986, judgment in this case offers a nuanced resolution to a complex scenario where strict corporate formation rules clashed with principles of fairness and good faith. By first affirming the stringent legal requirement for "property acquisitions" (zaisan hikiuke) to be detailed in a company's original articles of incorporation and the "absolute nullity" resulting from non-compliance, the Court upheld the protective aims of company law. However, it then astutely applied the overarching principle of good faith (shingisoku) to prevent the appellant company from abusively wielding this nullity as a shield against its long-acknowledged contractual obligations. This decision underscores the Japanese legal system's capacity to temper formal legal doctrines with equitable considerations to achieve justice in commercial dealings, particularly where parties have acted in reliance on an agreement over an extended period.