When Foreign Law is Misapplied: Japanese Supreme Court Steps in on International Family Case

Date of Judgment: March 18, 2008

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

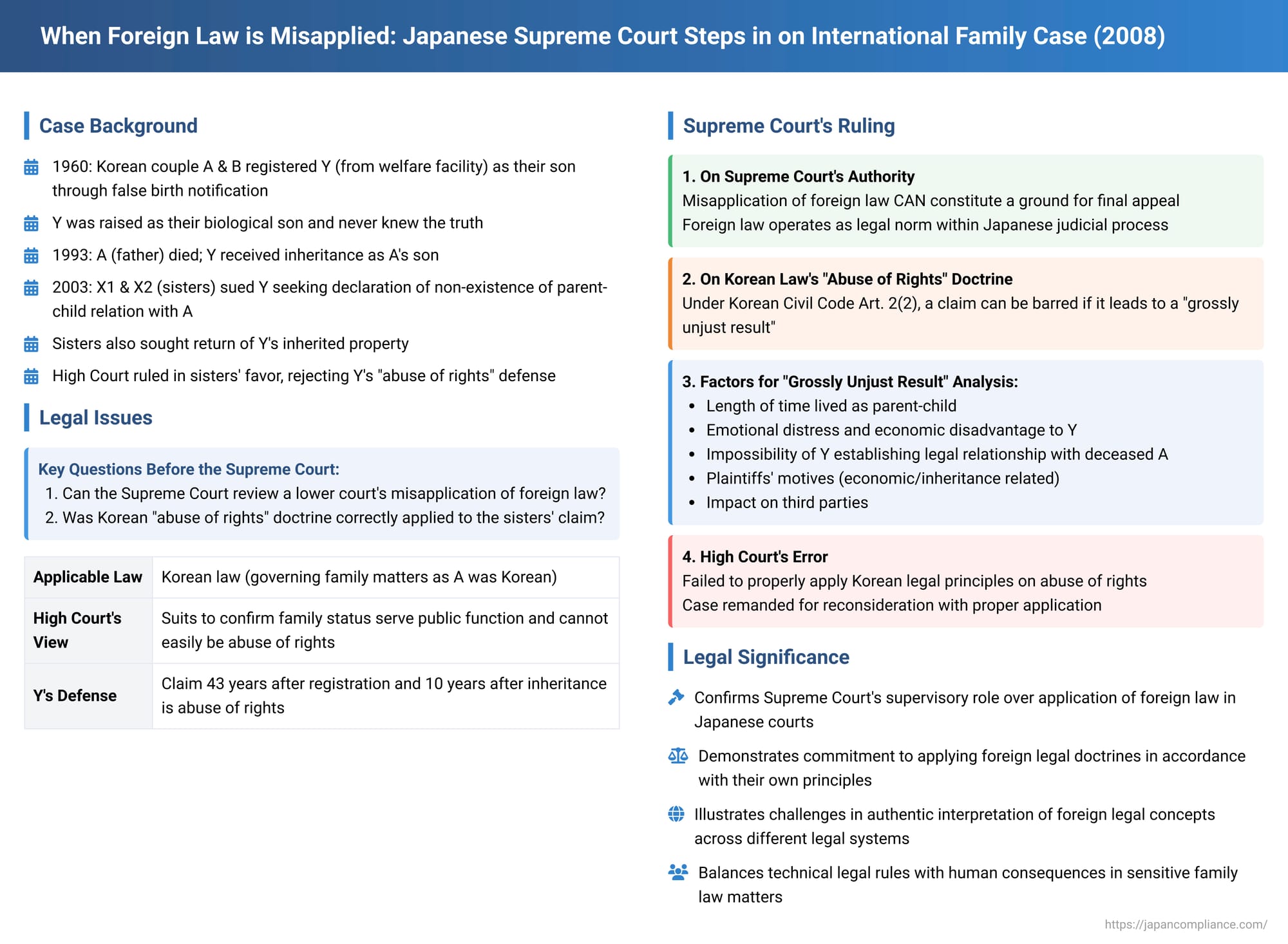

When Japanese courts handle international cases, they often apply foreign substantive law as determined by Japan's own conflict of laws rules (the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws, or its predecessor, the Horei). But what happens if a lower Japanese court misinterprets or misapplies that designated foreign law? A Supreme Court decision on March 18, 2008, involving a complex family dispute governed by Korean law, provided crucial clarification on the Supreme Court's authority to review such applications and underscored the importance of correctly interpreting foreign legal doctrines, such as the "abuse of rights."

The Factual Background: A "Paper Son" and a Belated Dispute

The case revolved around a family with Korean nationality and long-standing ties to Japan:

- A (Deceased Husband/Father) and B (Wife): A married couple, both Korean nationals.

- X1 and X2 (Plaintiffs): The eldest and second daughters of A and B, born in 1947 and 1950, respectively (also Korean nationals).

- C: A and B's biological firstborn son, who passed away at a young age.

- Y (Defendant): A man born in 1957. In 1960, A and B, desiring a son after the death of C, took Y from a welfare facility. They then registered Y in Japan through a false birth notification, claiming he was their second son, born in Japan. This false registration was subsequently recorded in their Korean family register (hojeok).

- Upbringing and Belief: A and B raised Y as if he were their biological son, and Y grew up believing this to be true. A never revealed to Y that he was not his biological son.

- A's Death and Inheritance: A passed away in 1993. Following his death, Y, recognized as A's son, participated in an estate division agreement with X1, X2, and B (the mother), and Y received a substantial portion of A's estate.

- Dispute Emerges Years Later: In 2003, approximately 10 years after A's death and 43 years after Y's registration as their son, the daughters, X1 and X2, abruptly challenged Y's status. They filed a lawsuit seeking a court declaration of the non-existence of a legal parent-child relationship between the deceased A and Y. They also sought the return of the inherited property Y had received.

- (A separate judgment confirming the non-existence of a maternal parent-child relationship between B (the mother) and Y had already become final in 2006.)

The High Court, acting as the original trial court for this appeal to the Supreme Court, had ruled in favor of X1 and X2. It determined that under Korean law (which was correctly identified as the governing law for A's parent-child relationships as A was Korean), no biological link existed between A and Y. Critically, the High Court rejected Y's defense that X1 and X2's claim, brought after so many decades of Y living as A's son and after the estate division, constituted an "abuse of rights" (権利の濫用 - kenri no ranyō). The High Court reasoned that a lawsuit to confirm family status serves the public function of ensuring the accuracy of official family registers and therefore could not easily be deemed an abuse of rights.

The Core Legal Questions Before the Supreme Court

The case presented two main issues for the Supreme Court:

- Is a misapplication or misinterpretation of the applicable foreign substantive law (here, Korean law) by a lower Japanese court a permissible ground for a petition for acceptance of final appeal to the Supreme Court of Japan?

- If so, did the High Court correctly apply Korean law, particularly its doctrine of "abuse of rights," to X1 and X2's claim to deny the A-Y parent-child relationship?

The Supreme Court's Rulings

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for reconsideration, delivering important pronouncements on both procedural and substantive points:

1. Misapplication of Foreign Law as a Ground for Appeal to the Supreme Court:

The Supreme Court, by proceeding to scrutinize the lower court's application of Korean law and ultimately finding an error, implicitly and effectively affirmed the prevailing legal view in Japan:

- A misinterpretation or misapplication of the designated foreign substantive law by a lower Japanese court can constitute a ground for a petition for acceptance of final appeal under Article 318(1) of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure. This article allows for such petitions when the case involves "material matters concerning the construction of laws and regulations."

- Rationale: Foreign law, once designated as applicable by Japanese private international law rules, operates as a legal norm within the Japanese judicial process, similar to domestic law. The Supreme Court, as the highest court responsible for ensuring the uniform and correct interpretation of law, has a role in overseeing its proper application. This is particularly important for maintaining legal stability and ensuring just outcomes in an increasing number of international cases.

- The Court found that the present case, concerning the standards for determining the existence of a parent-child relationship under Korean law and the application of the abuse of rights doctrine within that context, was indeed a "material matter" warranting its review.

2. Interpretation of Korean Law on "Abuse of Rights" in Parent-Child Disputes:

The Supreme Court then undertook a detailed analysis of the relevant Korean law:

- Nature of the Korean Action to Confirm Non-Existence of Parent-Child Relationship (Korean Civil Code Art. 865): This legal action is designed to provide a definitive, universally binding judgment on the existence or non-existence of a biological parent-child relationship, thereby ensuring the accuracy of the family register (hojeok), which serves as public attestation of such relationships. In principle, if the registered status does not match the biological reality, a claim for confirmation of non-existence can be brought.

- Limitations and the Doctrine of Abuse of Rights (Korean Civil Code Art. 2(2)): However, the Supreme Court noted that Korean law itself places limitations on strictly reflecting biological truth in the family register (e.g., statutory time limits for actions to deny paternity). More importantly, the Court focused on the Korean Civil Code's general provision against the "abuse of rights" (Art. 2(2)).

- The SC's Interpretation of Korean "Abuse of Rights" in this Context: Citing Korean legal principles and a 1977 Korean Supreme Court precedent (which recognized an adoptive effect for a false birth registration made with adoptive intent where substantive adoption requirements were met, prioritizing established family realities), the Japanese Supreme Court held that a claim by a third party (like X1 and X2) to confirm the non-existence of a parent-child relationship between a person (Y) and their registered father (A) can be barred as an abuse of rights under Korean law if confirming the non-existence would lead to a "grossly unjust result."

- Factors to Consider for "Grossly Unjust Result": The determination of whether confirming non-existence would be grossly unjust requires a comprehensive consideration of various circumstances, including:

- The length of time the registered father (A) and child (Y) lived together as a de facto parent and child.

- The emotional distress and economic disadvantage that confirming non-existence would inflict upon Y and other affected parties.

- The possibility (or, as in this case where A was deceased, impossibility) of Y now establishing a legal parent-child relationship with A through other means, such as formal adoption.

- The motives and purposes of the plaintiffs (X1 and X2) in bringing the claim (here, seemingly economic, related to reclaiming inherited property).

- Whether any parties other than the plaintiffs would suffer significant disadvantage if the non-existence of the parent-child relationship were not confirmed.

3. The High Court's Error in Applying Korean Law:

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its application of Korean law. The High Court had failed to properly consider these specific factors relevant to the Korean doctrine of abuse of rights when it summarily rejected Y's defense. By stating that a suit to clarify family status could not easily be an abuse of rights without engaging in this detailed, fact-sensitive balancing test prescribed by Korean legal principles, the High Court had misapplied the governing foreign law. This misapplication was deemed an error of law that clearly affected the judgment.

Outcome and Remand

Consequently, the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case back to the High Court. The instruction was for the High Court to reconsider X1 and X2's claim in light of a proper application of the Korean law on abuse of rights, taking into account all the relevant circumstances as outlined by the Supreme Court. (On remand, the Nagoya High Court did find the claim to be an abuse of rights and dismissed X1 and X2's claim).

Significance and Commentary Insights

This 2008 Supreme Court decision carries dual importance:

- Supreme Court's Supervisory Role Over Foreign Law Application: The case strongly affirms the Supreme Court's jurisdiction and willingness to review how lower Japanese courts interpret and apply designated foreign substantive law. It treats significant errors in this regard as reviewable errors of law, not mere findings of fact.

- Deep Engagement with Foreign Legal Doctrine: The judgment demonstrates a serious attempt by the Japanese Supreme Court to understand and apply nuanced foreign legal doctrines, such as Korea's concept of "abuse of rights" in family law. It shows a commitment to ensuring that when foreign law governs, it is applied in a manner consistent with its own principles and jurisprudence.

- Critique Regarding the "Authenticity" of Interpretation: While the Supreme Court delved into Korean law, Professor Nishitani's commentary accompanying the case file raises a subtle but important critique. It suggests that the Supreme Court, while citing Korean legal principles, might not have fully captured the extent to which Korean law prioritizes established family realities, especially in cases of "paper adoptions" through false birth registrations where there was clear intent to raise the child as one's own and a long period of de facto family life. The commentary implies that a Korean court might have more readily found an effective adoptive relationship to exist from the outset, thereby precluding the non-existence claim altogether, rather than primarily relying on the abuse of rights doctrine to potentially achieve a similar protective outcome. This highlights the inherent challenges even for a top court in perfectly transposing and applying the intricate nuances of a foreign legal system.

Conclusion

This Japanese Supreme Court decision is a significant illustration of the complexities involved when domestic courts are tasked with applying foreign law. It firmly establishes that a misapplication of designated foreign law by lower courts is a matter reviewable by the Supreme Court of Japan, underscoring the importance of correctly interpreting international legal obligations. Furthermore, the case provides a detailed example of the judiciary engaging with foreign legal concepts like "abuse of rights" to ensure that the application of foreign law in Japanese courts leads to just and equitable outcomes, particularly in sensitive family law matters with profound human consequences. It also serves as a reminder of the ongoing dialogue and potential for differing perspectives when one legal system interprets the intricacies of another.