When Foreign Law Clashes with Local Values: Japan's Supreme Court on Public Policy and Divorce Property Rights

Date of Judgment: July 20, 1984

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

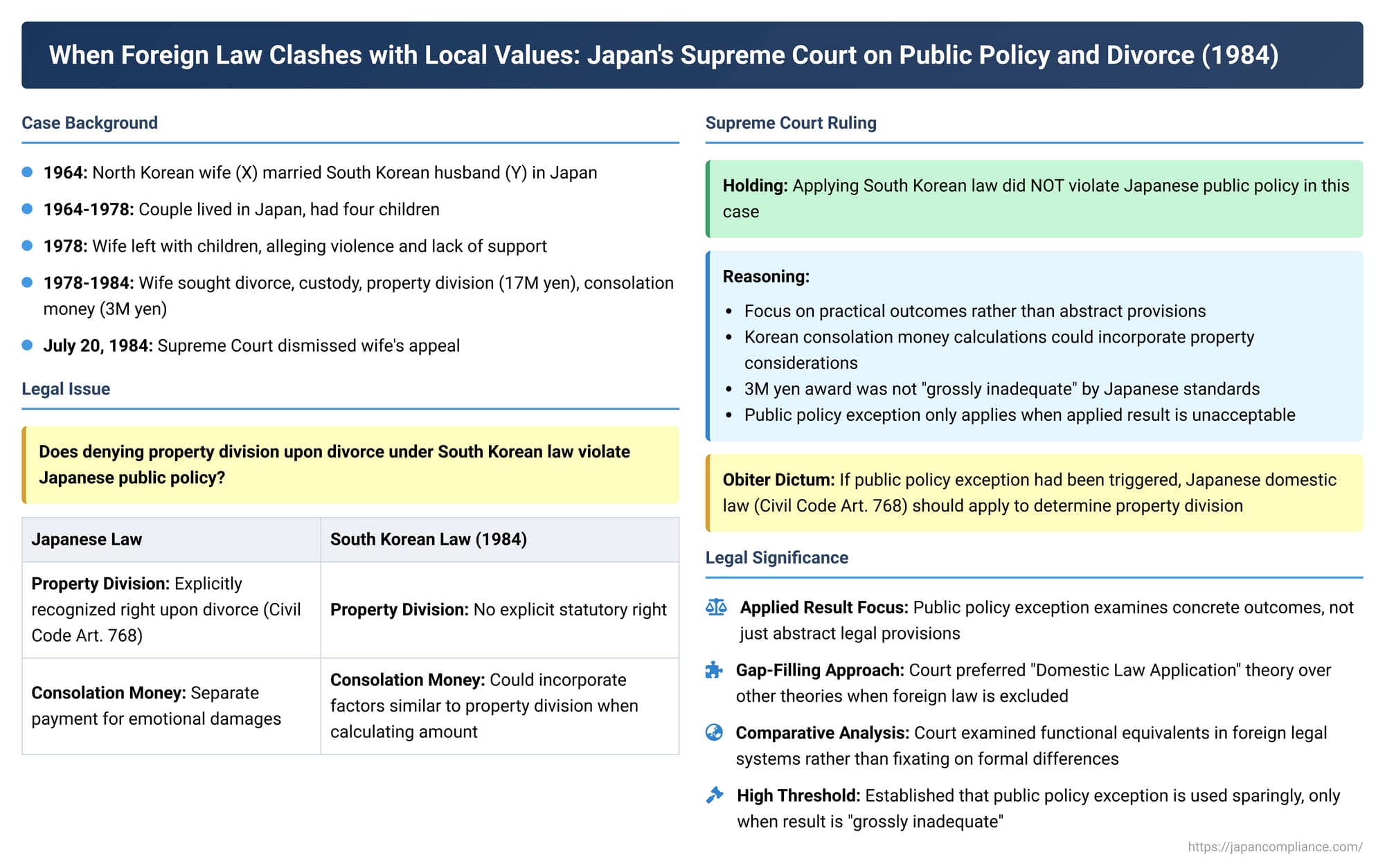

In the interconnected world of international legal relations, courts are often tasked with applying foreign laws. However, there are instances where the application of a designated foreign law might lead to a result that deeply offends the fundamental moral, social, or legal principles of the court's own jurisdiction (the "forum"). To guard against such outcomes, legal systems employ the "public policy" exception (公序 - kōjo, often translated as "public order" or "public policy and good morals"). This doctrine allows a court to refuse to apply an otherwise applicable foreign law if its application would be manifestly incompatible with the forum's core values. A significant Japanese Supreme Court decision issued on July 20, 1984, delves into this very issue, particularly in the sensitive context of international divorce and the division of marital property.

The Factual Scenario: A Cross-Border Marriage and Its Breakdown

The case involved a couple with differing nationalities residing in Japan:

- Ms. X, the wife and plaintiff, was a North Korean national.

- Mr. Y, the husband and defendant, was a South Korean national.

They had registered their marriage in Japan in 1964 and had lived there since, raising four children by 1974. Ms. X alleged that throughout their marriage, Mr. Y had failed to provide adequate financial support for the family and had subjected her to persistent violence. In 1978, Ms. X left the marital home with their four children. Subsequently, she filed a lawsuit against Mr. Y seeking a divorce, custody of their children, a division of marital property amounting to 17 million yen, and consolation money (慰謝料 - isharyō, for emotional distress) of 3 million yen.

The Legal Challenge: Foreign Law Denying Property Division

Under Japan's private international law rules at the time (Article 16 of the then-applicable Horei, or Act on Application of Laws – a provision with different rules than the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws Article 27), the effects of divorce, including property division, were to be determined by the husband's national law. In this case, that was South Korean law. A crucial point of contention arose because the South Korean Civil Code, as it stood at that time, did not explicitly recognize a spouse's right to claim a division of property upon divorce.

The first instance court (Osaka District Court, Kishiwada Branch) granted the divorce, awarded custody to Ms. X, and ordered Mr. Y to pay 3 million yen in consolation money. However, it denied Ms. X's claim for property division, applying South Korean law. The court explicitly stated that applying Korean law to deny property division was not, in this instance, contrary to Japan's public policy or good morals (under Article 30 of the old Horei, the precursor to Article 42 of the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws). The Osaka High Court upheld this decision. Ms. X then appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the denial of property division based on Korean law violated Japanese public policy.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Focusing on the "Applied Result"

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of July 20, 1984, dismissed Ms. X's appeal. Its reasoning provides valuable insight into the application of the public policy exception:

The Court acknowledged that the South Korean Civil Code did not provide for a distinct right to claim property division (財産分与 - zaisan bun'yo) upon divorce. However, it looked beyond this formal absence. The Court noted that when calculating the amount of consolation money (isharyō) payable by the liable spouse under Korean law (pursuant to Articles 843 and 806 of the Korean Civil Code), the Korean courts could take into account various factors. These factors included the existence and nature of any property acquired through the spouses' mutual cooperation during the marriage.

This meant, in the Supreme Court's view, that the Korean system, despite lacking a separate claim for property division, had a mechanism (via the calculation of consolation money) through which a similar financial outcome could substantially be achieved. Depending on how these property-related factors were weighed in the consolation money award, the result could be practically identical to recognizing a property division claim.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the mere fact that Korean law did not recognize a separate right to property division did not, in itself, automatically render its application contrary to Japanese public policy.

The public policy exception would only be triggered, the Court elaborated, if the amount of consolation money deemed payable under Korean law – taking into account all relevant circumstances of the marriage (such as the parties' nationalities, life histories, financial situations, need for support, and, crucially, the property acquired through their joint efforts during the marriage) – was found to be grossly inadequate when measured against Japanese social consensus regarding overall divorce-related financial settlements (which in Japan encompass both consolation money and property division).

Only if such gross inadequacy was evident would the application of Korean law to deny a separate property division claim be considered offensive to Japanese public policy. In such a scenario, Korean law would be set aside by virtue of the public policy clause (Horei Article 30), and Japanese law (specifically Article 768 of the Japanese Civil Code, which deals with property division) would then be applied to determine the amount and method of property division.

Applying this reasoning to Ms. X's case, the Supreme Court found that the 3 million yen consolation money awarded to her under Korean law was not grossly inadequate when viewed against the backdrop of Japanese social norms for comprehensive divorce settlements. Consequently, there was no basis to exclude the application of Korean law and apply Japanese property division rules instead.

The "Public Policy" Exception: A Focus on Concrete Outcomes

This judgment underscores a key aspect of the public policy doctrine: the focus is generally on the concrete result of applying the foreign law in a specific case, rather than on an abstract condemnation of the foreign law provision itself. Even if a foreign rule, viewed in isolation, appears to deviate from the forum's principles (like the absence of a distinct property division right), if the foreign legal system as a whole provides mechanisms that can lead to a substantively fair or acceptable outcome in the particular circumstances, the public policy exception may not be invoked.

The commentary by Professor Hayakawa accompanying this case notes that while the older Horei Article 30 was phrased as "when its provisions are contrary to public order or good morals," this Supreme Court decision effectively aligned its interpretation with the clearer wording of the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws Article 42 (and the intermediate Horei Article 33), which states "when the application of its provisions is contrary to public order or good morals" (emphasis added). This confirms that the judiciary, even under the older statute, was concerned with the actual impact of applying the foreign law.

What If Public Policy Had Been Invoked? The Supreme Court's Obiter Dictum

Interestingly, the Supreme Court, in its reasoning (判旨 I), went on to state what should happen if public policy had been triggered to exclude the application of Korean law. It indicated that in such a case, Japanese law (specifically, the Japanese Civil Code provision on property division, Article 768) should be applied to determine the property division. Since public policy was not ultimately invoked in this case, this statement was obiter dictum (a judicial comment made in passing that is not essential to the decision and therefore not binding as precedent), but it nonetheless provided a significant indication of the Supreme Court's thinking on the "aftermath" of invoking public policy.

The question of what legal rule to apply once a foreign law has been set aside on public policy grounds has been a subject of academic debate. Broadly, two main theories exist:

- Gap Affirmation Theory (欠缺肯定説 - kekketsu kōtei setsu): This theory posits that the exclusion of the foreign law creates a legal vacuum or "gap" that needs to be filled. Several ways to fill this gap have been proposed:

- Domestic Law Application (内国法適用説 - naikokuhō tekiyō setsu): Apply the law of the forum (in this case, Japanese law). This was the approach favored by the Supreme Court in its obiter dictum.

- Supplementary Connection (補充連結説 - hojū renketsu setsu): Re-determine the applicable law by finding another connecting factor, perhaps pointing to the law of a place with the next closest connection to the issue, excluding the rejected law.

- General Principles of Justice (条理説 - jōri setsu): Decide based on overarching principles of equity and fairness.

- Gap Denial Theory (欠缺否認説 - kekketsu hinin setsu): This theory argues that no actual legal gap arises. The act of excluding the foreign law on public policy grounds itself dictates the outcome. For example, if a foreign law that completely prohibits divorce is deemed contrary to public policy, the result is simply that divorce is permitted. There is no need to then formally "apply" another law to reach this conclusion.

Professor Hayakawa's commentary indicates that the Gap Denial Theory is, in fact, the prevailing view in Japanese academia. In straightforward "yes/no" issues like the permissibility of divorce, both theories often lead to the same practical result. If the foreign law's outcome (e.g., "no divorce") is rejected, the only alternative ("divorce allowed") stands.

However, for issues involving quantitative judgments, such as the amount of monetary compensation or property division, the theories can lead to different outcomes. Consider a hypothetical: Japanese law might award 10 million yen in a divorce settlement. Foreign Law X, if applied, would award only 2 million yen. Foreign Law Y would award 4 million yen. Assume the Japanese public policy threshold is that any award below 3 million yen is unacceptable.

- If Law X (2 million) is the applicable foreign law, its application would be contrary to public policy.

- Under the Domestic Law Application theory, the court would apply Japanese law, potentially awarding 10 million yen.

- Under the Gap Denial Theory, the court might award an amount at the public policy minimum, say 3 million yen.

- If Law Y (4 million) is the applicable foreign law, it exceeds the public policy threshold, so it would be applied, resulting in a 4 million yen award.

The Gap Denial theory critiques the Domestic Law Application theory by pointing out a potential "reversal phenomenon": applying a less generous foreign law (Law X) could paradoxically result in a much higher award (10 million under Japanese law) if public policy is triggered, compared to applying a more generous (but still foreign) law (Law Y, giving 4 million) where public policy isn't triggered. This outcome might seem problematic if the public policy exception is meant to be used sparingly as a last resort. Conversely, a challenge for the Gap Denial theory is the practical difficulty in precisely determining the "minimum threshold" required by public policy without reference to some concrete legal norm.

The Supreme Court in this 1984 case, following a similar stance in a 1977 decision, signaled its preference for the domestic law application method, a view shared by many lower courts then and since. It's suggested that judges, accustomed to the framework of applying substantive legal rules to facts, may find the Domestic Law Application theory more aligned with their typical adjudicative process than the Gap Denial theory, which might appear to derive a solution without explicitly applying a specific substantive law.

Conclusion: Nuance in Public Policy and Its Aftermath

The Supreme Court's July 20, 1984 decision is a significant case in Japanese private international law. It clearly illustrates that the public policy exception is applied with nuance, scrutinizing the substantive outcome of applying a foreign law rather than just its formal provisions. Furthermore, through its obiter dictum, the Court contributed to the ongoing discussion about the proper legal path to take once a foreign law is indeed set aside on public policy grounds, leaning towards the application of Japanese domestic law. This case continues to inform the understanding of how Japanese courts balance the imperative to apply designated foreign laws with the need to protect fundamental domestic legal principles.