When Family Isn't Family: A Japanese Ruling on Guardians, Trust, and a Limit to the 'Relative Theft' Doctrine

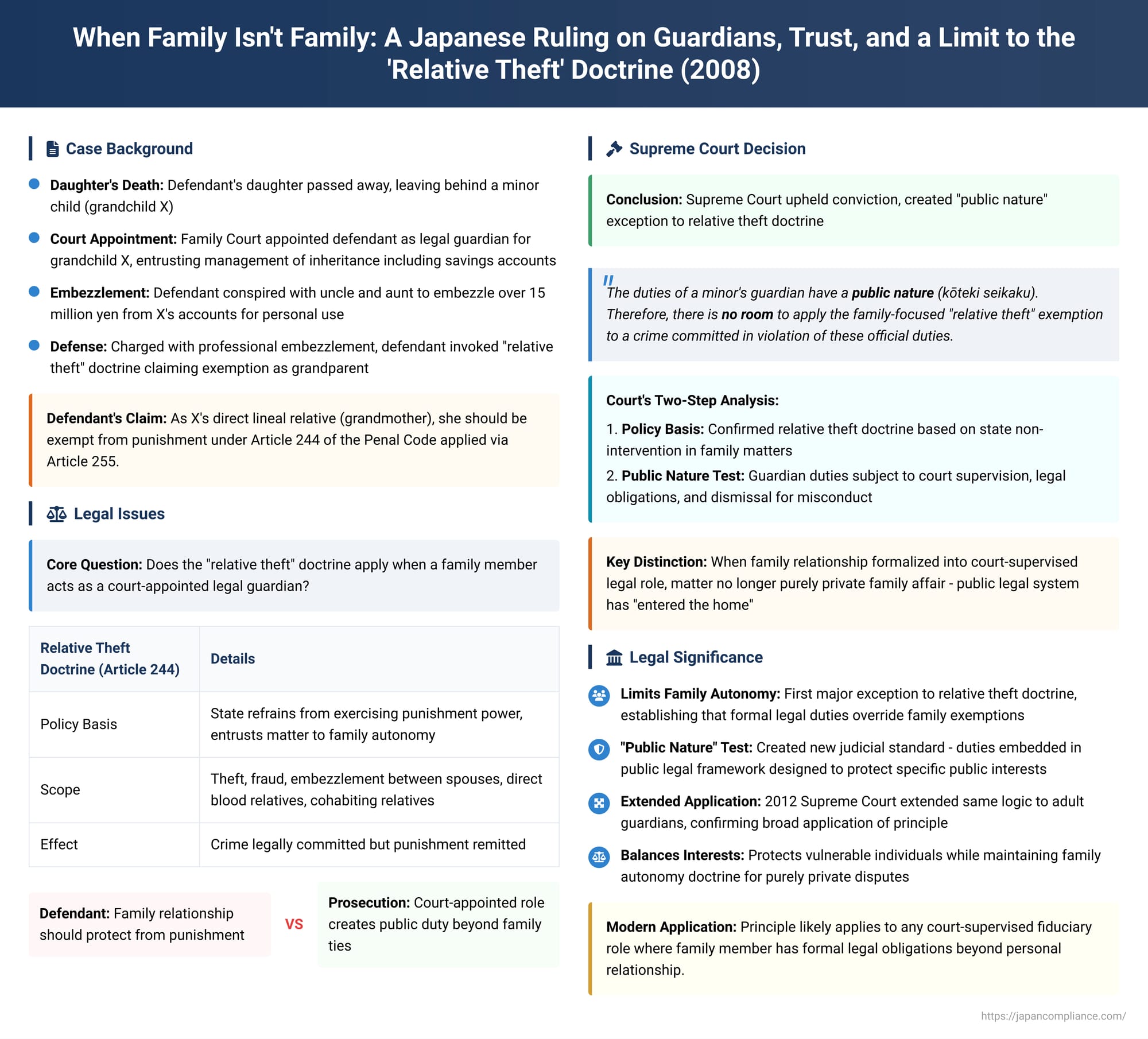

In Japan, a unique legal doctrine known as "relative theft" (shinzoku sōtō-rei) holds that certain property crimes committed between close family members are exempt from punishment. Based on the long-standing principle that "the law does not enter the home," this provision reflects a state policy of leaving internal family disputes to the family's own autonomy. But what happens when a family relationship is formalized into a legal duty supervised by the courts? Can a grandmother who embezzles from her own grandchild still claim the family exemption if she was acting as the grandchild's court-appointed legal guardian?

This critical question was at the center of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 18, 2008. The Court's ruling carved out a major exception to the "relative theft" doctrine, finding that when a familial role takes on a "public nature," the legal obligations of that role override the traditional family exemption.

The Facts: A Grandmother's Betrayal of Trust

The defendant in the case was a woman whose daughter had passed away. The Family Court subsequently appointed her as the legal guardian for her minor grandchild, X, entrusting her with the management of X's inheritance, including his savings accounts. This role made her a fiduciary responsible for handling X's finances "on business" (gyōmu-jō).

However, the defendant conspired with the grandchild's uncle and aunt to embezzle more than 15 million yen from X's accounts for their own use. When charged with professional embezzlement, a serious felony, the defendant invoked the "relative theft" doctrine. She argued that because the victim, X, was her grandson—a direct lineal relative by blood—she should be exempt from punishment under Article 244 of the Penal Code, which is applied to embezzlement via Article 255.

The "Relative Theft" Doctrine: A Policy of Non-Intervention

The "relative theft" doctrine, outlined in Article 244 of the Penal Code, is a special provision that remits the punishment for theft, fraud, and embezzlement committed between spouses, direct blood relatives, and other relatives living together. It also makes prosecution for such crimes between other relatives dependent on a formal complaint from the victim.

The prevailing legal theory, which the Supreme Court affirmed in this decision, is that this doctrine is not based on the idea that the crime is less wrong or that the perpetrator is less culpable. Rather, it is based on a "policy consideration that for certain property crimes between relatives, it is more desirable for the state to refrain from exercising its power of punishment and to entrust the matter to the autonomy of the relatives". It is a policy of non-intervention in family affairs. The crime is still legally committed; the state simply chooses not to impose a penalty.

The Lower Courts' Reasoning: The Role of the Family Court

The lower courts rejected the defendant's claim for exemption. The Fukushima District Court reasoned that the defendant's authority to manage her grandchild's property was based not on their personal relationship, but on her appointment by the Family Court. It held that this involvement of a non-relative third party—the court system—took the matter outside the scope of a purely private family dispute. The Sendai High Court agreed, stating that a guardian is granted power by the law as part of the protection of minors, which is distinct from a situation where a relative is entrusted with property management based on their family relationship alone.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The "Public Nature" Exception

The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, taking the opportunity to provide a definitive ruling on the issue on its own authority. The Court established a new and powerful exception to the "relative theft" doctrine, centered on the concept of "public nature."

The Court's reasoning proceeded in two steps:

- Affirming the Doctrine's Policy Basis: First, the Court explicitly endorsed the "policy theory" as the foundation of the "relative theft" doctrine, confirming its view that the rule is based on the state's decision to refrain from interfering in family matters.

- Creating the "Public Nature" Exception: Second, the Court analyzed the legal nature of a court-appointed guardian's duties under Japan's Civil Code. It observed that a guardian has a legal duty to "faithfully manage" the ward's property with the "care of a good manager". This duty exists regardless of whether the guardian is a relative and is subject to the direct supervision of the Family Court, which can even dismiss the guardian for misconduct.

Based on this legal structure, the Court announced its groundbreaking conclusion:

"Thus, the duties of a minor's guardian have a public nature (kōteki seikaku)."

Because the defendant was not acting merely as a grandmother but as a fiduciary operating within a formal, court-supervised system designed for the public good (the protection of a minor), her duties were imbued with this "public nature." The Court therefore concluded that there was "no room" to apply the family-focused "relative theft" exemption to a crime committed in violation of these official duties.

Analysis and Implications: What Does "Public Nature" Mean?

The Supreme Court's "public nature" test is a significant judicial innovation. The concept does not simply mean that a government body is involved. Rather, it refers to a duty that is embedded in a public legal framework designed to protect a specific public interest—in this case, the welfare of a minor. The duty is a legal obligation defined by statute, not a mere moral or familial one.

By creating this exception, the Court reasoned that when a family relationship is formalized into a court-supervised legal role, the matter is no longer a purely private family affair. The public legal system has already "entered the home" by establishing a formal structure of duties and oversight. Therefore, the policy of non-intervention no longer applies.

The scope of this ruling is significant. In a 2012 decision, the Supreme Court extended the same logic to the guardians of adults, confirming that the "public nature" test is not limited to minors. Legal analysis suggests the principle is closely tied to the crime being committed in the course of the guardian's official duties (i.e., professional embezzlement). If the defendant had, for example, stolen a piece of jewelry from her grandchild's room in a context completely unrelated to her financial management duties, the "relative theft" exemption might still have applied.

Some critics have raised concerns that the Court's creation of a new exception to a clear statute violates the principle of legality (the idea that crimes and punishments must be strictly defined by law). However, the Court appears to preempt this by framing the "relative theft" doctrine itself not as a core element of the crime, but as a "special exception for punishment" based on policy. The judiciary generally has more latitude in interpreting the scope and limits of such policy-based exceptions than it does in defining the core elements of a crime.

Conclusion: The Limits of Family Autonomy

The 2008 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling that places a clear and necessary limit on Japan's unique "relative theft" doctrine. It establishes that when a family member assumes a formal, court-appointed role as a legal guardian, they step out of the purely private realm of the family and into a role of public trust.

The principle is clear: the legal obligations that come with a position of a "public nature" override the traditional exemption granted to family members. The ruling sends a powerful message that while the law may hesitate to intervene in private family disputes, it will not stand aside when a formal legal system designed to protect the vulnerable is abused. In such cases, the law will enter the home to uphold justice, regardless of the family ties involved.