When Does the Clock Start? Japan's Supreme Court on the Inheritance Deliberation Period for Unaware Heirs

Date of Judgment: April 27, 1984 (Showa 59)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 57 (o) No. 82 (Claim for Loan Repayment, etc.)

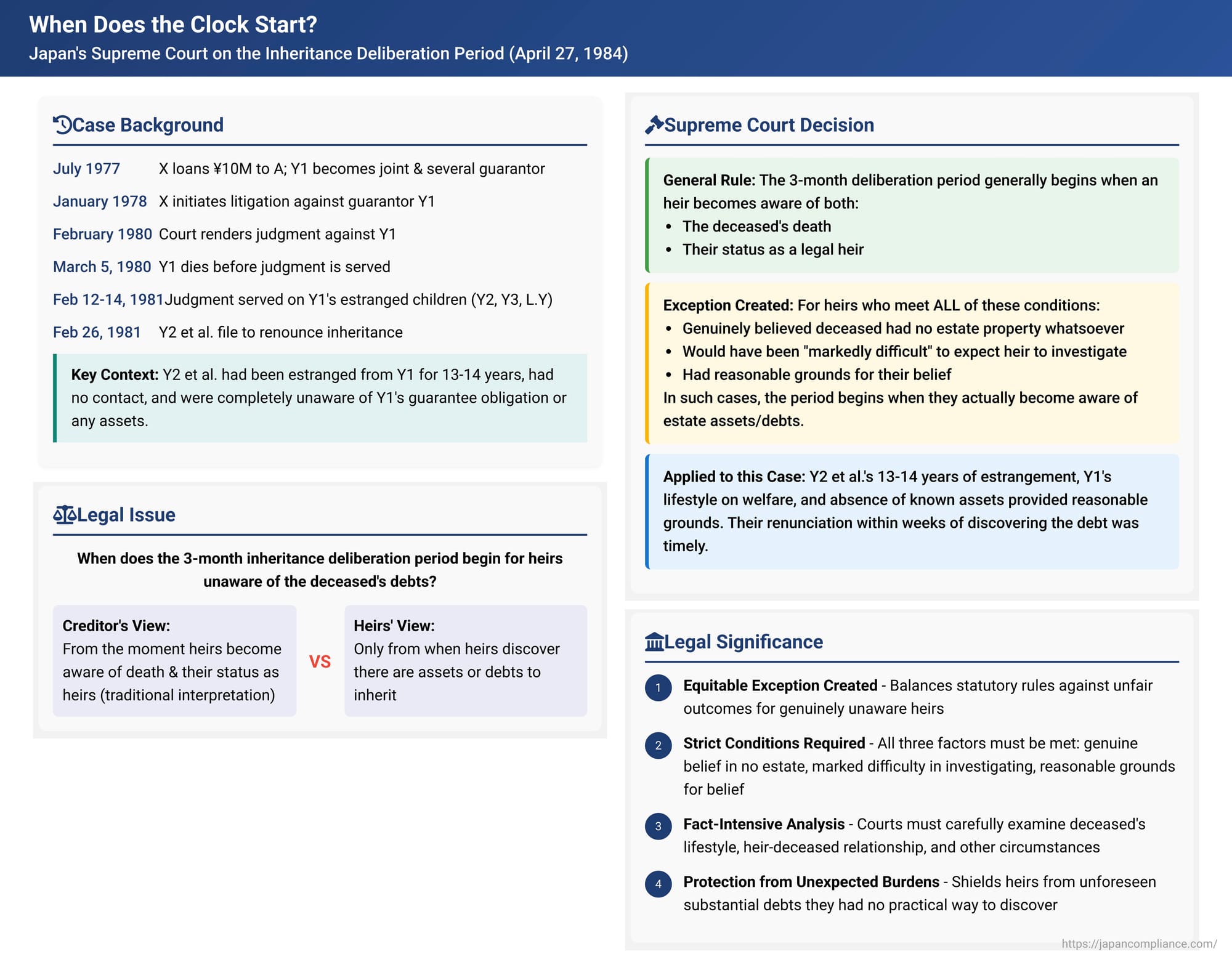

When an individual inherits an estate in Japan, they are granted a crucial three-month "deliberation period" (熟慮期間 - jukuryo kikan) under Article 915, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code. During this time, the heir must decide whether to simply accept the inheritance (assets and debts), accept it with limitations (qualified acceptance), or renounce it entirely. A critical question is: when exactly does this three-month clock begin to tick, especially for heirs who are unaware of the deceased's debts and believe there is no significant estate to consider? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a landmark clarification on this issue in its decision on April 27, 1984, establishing an important equitable exception to the general rule.

Facts of the Case: An Unexpected Debt and Estranged Heirs

The case involved a complex sequence of events surrounding a guarantee obligation undertaken by the deceased.

- The Original Debt and Guarantee: In July 1977, X (the plaintiff/appellant creditor) entered into a quasi-loan agreement for ¥10 million with an individual named A, where A was the borrower. On the same day, Y1 (the original defendant in the lawsuit) acted as a joint and several guarantor for A's debt to X.

- Litigation Against the Guarantor Y1: In January 1978, X initiated legal proceedings against Y1 to enforce the guarantee. On February 22, 1980, the first instance court rendered a judgment in favor of X, holding Y1 liable.

- Death of Guarantor Y1: However, Y1 passed away on March 5, 1980, crucially before this first instance judgment could be formally served upon him. His death interrupted the ongoing lawsuit.

- Y1's Heirs and Their Circumstances: Y1's legal heirs were his children, Y2, Y3, and L.Y (the defendants/appellees in the Supreme Court, collectively referred to as "Y2 et al."). A key factor in the case was the profound estrangement between Y1 and his children. Since around 1966-1967 (approximately 13 to 14 years prior to Y1's death), Y2 et al. had severed ties with Y1. This estrangement stemmed from Y1's reported lifestyle: he allegedly had no steady employment, was heavily involved in gambling, and was the source of constant family discord. Consequently, his children had no ongoing contact with him and were completely unaware of his financial affairs, including the substantial guarantee obligation he had undertaken.

- Y1's Financial Situation at Death: At the time of his passing, Y1 was reportedly receiving public welfare, including both living assistance and medical aid. He had no known positive assets that his children could inherit.

- Heirs Become Aware of the Debt: The first instance judgment (which had been rendered against Y1 before his death) was formally served on his heirs, Y2 and Y3, in February 1981 (Y2 on February 12th, Y3 on February 13th). L.Y was informed of this development by Y3 on February 14, 1981. It was only through the service of this court judgment that Y2 et al. first became aware of the significant guarantee debt their estranged father had incurred.

- Renunciation of Inheritance by Heirs: Upon discovering this unexpected and substantial liability, Y2 et al. acted promptly. They filed declarations to renounce their inheritance from Y1 with the Family Court on February 26, 1981. The Family Court officially accepted these renunciations on April 17, 1981.

- High Court Ruling on the Renunciation: X, the creditor, continued the lawsuit against Y2 et al. as Y1's successors. The validity of their inheritance renunciation became a central issue. The High Court ruled in favor of Y2 et al., finding their renunciations valid. It interpreted Article 915(1)'s phrase—"when an heir becomes aware that an inheritance has commenced for himself/herself"—to mean that the deliberation period starts not merely when the heir knows of the deceased's death and their own status as an heir, but additionally, when they become aware that there is an actual estate (comprising either positive assets or negative assets like debts) to be inherited. Since Y2 et al. only learned of Y1's debt (a significant negative component of the estate) upon being served with the judgment against Y1, the High Court concluded that their three-month deliberation period began from that point. Therefore, their renunciations, filed shortly thereafter, were deemed timely. Consequently, the High Court overturned the (now symbolic) first instance judgment against Y1 and dismissed X's claim against Y2 et al.

- X's Appeal to the Supreme Court: X, the creditor, appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the General Rule with a Key Exception

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's ultimate conclusion that the heirs' renunciations were valid, though it refined the legal reasoning.

The Supreme Court articulated its position as follows:

- The General Principle for the Start of the Deliberation Period:

The Court began by reaffirming the general rule regarding the commencement of the three-month deliberation period under Article 915, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code. This period allows an heir to choose between simple acceptance of the inheritance, qualified acceptance (accepting assets only to the extent that they cover debts), or complete renunciation. The Court stated that this three-month period is founded on the premise that an heir, upon learning of (a) the facts causing the inheritance to commence (i.e., the death of the deceased) and (b) the fact that they themselves are a legal heir as a result, will typically be able, within three months from knowing these facts, to investigate and ascertain (or be reasonably capable of ascertaining) the existence, nature, and extent of the inheritable assets (both positive and negative). Once this information is, or should be, known, the prerequisites for making an informed choice about acceptance or renunciation are considered met.

Therefore, the deliberation period generally begins to run from the time the heir becomes aware of both the deceased's death and their own status as a legal heir. This largely aligns with a long-standing precedent from the Daishin'in (Great Court of Cassation, Japan's highest court before the current Supreme Court) dating back to Taisho 15 (1926). - An Exception to the General Principle for Unaware Heirs:

However, the Supreme Court carved out a significant, fact-dependent equitable exception to this general rule:

The Court stated that if an heir, despite knowing of the deceased's death and their own status as an heir, fails to make a limited acceptance or renunciation within the initial three-month period, and this failure was because:- The heir genuinely believed that the deceased had no inheritable property whatsoever (neither positive assets nor negative assets like debts); AND

- Considering the deceased's life history, the nature of the relationship (or lack thereof) between the deceased and the heir, and other various relevant circumstances, it would have been markedly difficult to expect the heir to have conducted an investigation into the existence of any estate property; AND

- The heir had reasonable grounds for believing that no such estate property existed;

THEN, in such exceptional circumstances, it would be inappropriate and unfair to rigidly calculate the start of the deliberation period from the time the heir first learned of the death and their heir status.

Instead, under these specific conditions, the deliberation period should be deemed to commence from the time the heir actually became aware of the existence of all or part of the estate property (assets or debts), or from the time they ordinarily should have been able to become aware of it.

Application to the Facts of the Case:

The Supreme Court found that the circumstances of Y2 et al. fit this exception:

- Y2 et al. were aware of Y1's death and their status as his heirs.

- However, due to Y1's estranged lifestyle (marked by gambling, lack of steady employment, and family disputes leading to over a decade of no contact) and his reliance on public assistance at the time of his death, Y2 et al. genuinely believed that Y1 had left no estate whatsoever, either assets or debts.

- Given this long period of estrangement and Y1's apparent financial state, it was considered exceptionally difficult to expect Y2 et al. to proactively investigate the possibility of unknown assets or, particularly, unknown substantial debts like the guarantee.

- Therefore, their belief that Y1 left no estate was deemed to have reasonable grounds.

- In light of this, the deliberation period for Y2 et al. correctly began when they were first made aware of Y1's significant guarantee debt, which occurred upon the service of the first instance court judgment against Y1 upon them in February 1981.

- Their subsequent renunciation of inheritance, filed on February 26, 1981, was thus well within the three-month period calculated from this later starting point and was therefore valid.

The Supreme Court acknowledged that the High Court's broader formulation of the rule (suggesting the clock always starts only when an heir recognizes some estate property) was a misinterpretation of the law. However, because the specific facts of this case fell squarely within the exception articulated by the Supreme Court, the High Court's ultimate conclusion—that the renunciations were valid and X's claim against Y2 et al. should be dismissed—was correct.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1984 Supreme Court decision is of profound importance in Japanese inheritance law:

- Reaffirmation of General Rule and Creation of a Vital Exception: The judgment upholds the traditional starting point for the deliberation period (knowledge of death and heir status) but introduces a crucial, equity-based exception for heirs who are genuinely and reasonably unaware of any estate, particularly hidden debts.

- Strict Conditions for the Exception: It is important to note that the exception is narrowly defined and requires the heir to demonstrate all the qualifying conditions: (a) a belief that no estate property at all existed, (b) this belief being the reason for inaction within the initial three months, (c) marked difficulty in being expected to investigate, and (d) reasonable grounds for the belief.

- Fact-Intensive Inquiry for "Reasonable Grounds": Determining whether an heir had "reasonable grounds" for their belief and whether investigation was "markedly difficult" is a highly fact-specific assessment. Courts will look at the deceased's lifestyle, their financial visibility, the nature and duration of the relationship (or estrangement) between the deceased and the heir, and any other relevant circumstances. The PDF commentary mentions a later Tokyo High Court case (Heisei 15.9.18 - September 18, 2003) where heirs who doubted the validity of an old alleged debt or believed it was likely statute-barred were found to have reasonable grounds for their initial inaction before being formally pursued.

- Focus on Protecting Heirs from Unexpected Burdens: The exception is clearly designed to protect heirs from being unfairly saddled with substantial, unknown debts of a deceased relative, especially when they had no reason to suspect such liabilities and no practical means of discovering them within the initial three-month window.

- Scope of the "No Estate Property at All" Condition: The PDF commentary touches upon a potential ambiguity: the Supreme Court's wording in this 1984 case specifically refers to the heir believing "the deceased had no inheritable property at all." This raises the question of whether the exception could apply if an heir knew of some very minor positive assets but was later blindsided by massive, unexpected debts that far outweighed those assets. The strict wording of the 1984 judgment seems to limit the exception to situations where the heir believed in the complete absence of any estate. If any estate property (positive or negative) was recognized by the heir, the general rule for the deliberation period might still apply from the initial awareness of death and heir status, though this remains a point of legal discussion and may depend on further case-by-case analysis.

- Judicial Development vs. Legislative Prerogative: It is noteworthy that one Supreme Court Justice (Miyazaki) dissented in this case. The dissent argued that creating such a significant exception to a statutory rule strayed from judicial interpretation into the realm of legislative action and could potentially undermine legal stability and prejudice creditors who are unaware of the heirs' subjective beliefs. The majority, however, found the equitable considerations compelling enough to warrant the exception.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1984 decision represents a significant balancing act between the statutory framework for inheritance acceptance and renunciation and the equitable need to protect heirs from unforeseen and potentially ruinous inherited debts, particularly in cases of long-term estrangement and lack of information. While affirming the general rule for the commencement of the three-month deliberation period, the Court carved out a carefully conditioned exception. This exception allows the deliberation period to start from the later point of discovering estate assets or debts, provided the heir genuinely and with reasonable grounds believed no estate existed and could not reasonably have been expected to investigate earlier. This ruling underscores the Japanese legal system's capacity to adapt strict statutory provisions to achieve fairness in compelling individual circumstances.