When Does Coverage Begin? Japan's Supreme Court on Retroactive Effect in Social Insurance (1965)

TL;DR

Japan’s Supreme Court (Y Co. case, 1965) held that employees automatically acquire Health Insurance Act and Employees’ Pension Insurance Act coverage from their first day of work. The administrative “confirmation” merely validates that fact and retroactively relates back, so premiums and benefits both run from the employment date—regardless of when the employer files the paperwork.

Table of Contents

- Background: Delayed Notification and Retroactive Premiums

- The Legal Challenge: Effective Date of Qualification

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Retroactivity Upheld

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

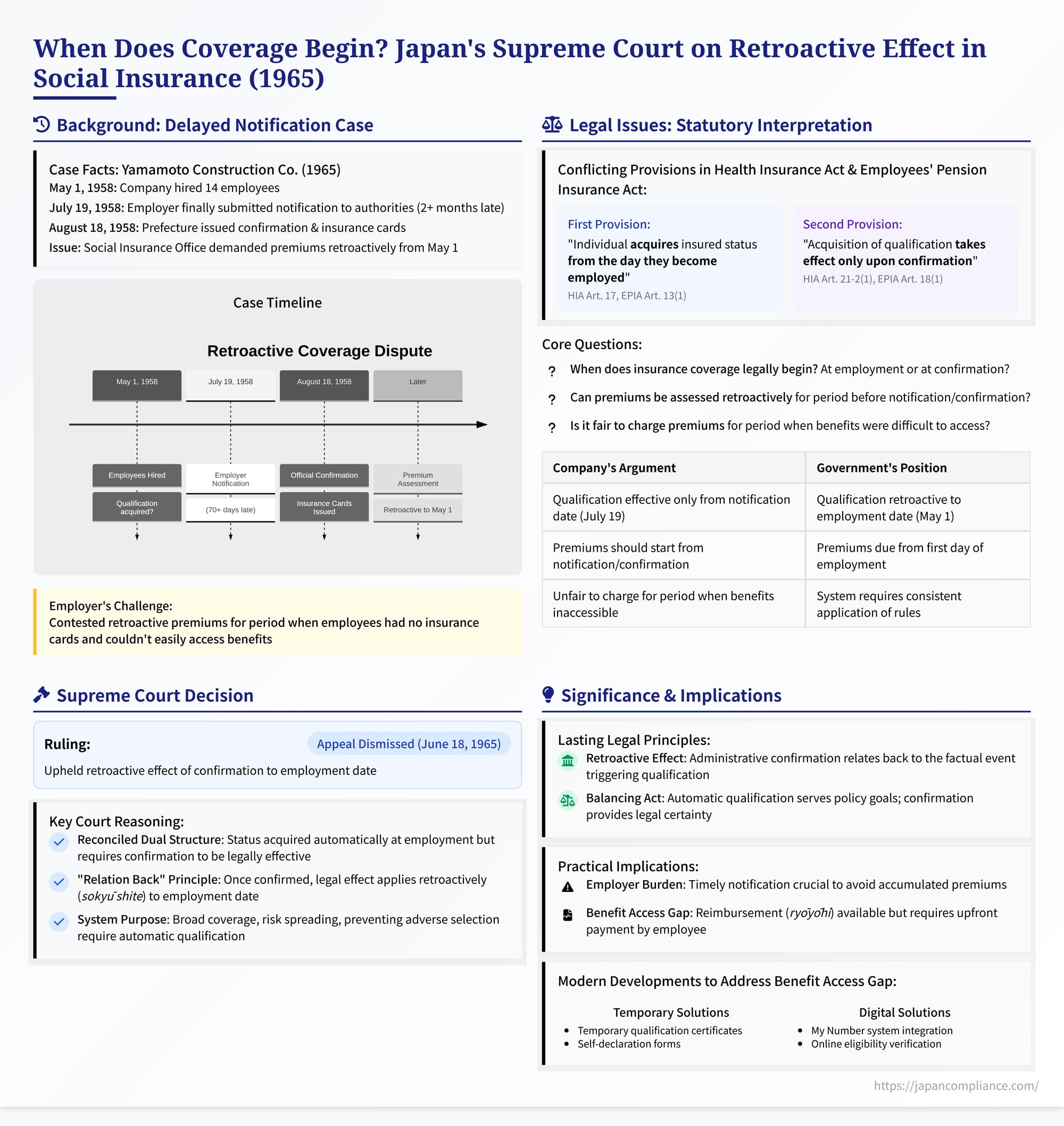

In compulsory social insurance systems covering employees, a seemingly simple question can have significant financial implications for both employers and employees: When does insurance coverage legally begin? Is it the moment an employee starts work at a covered establishment, or only after the employer notifies the authorities and administrative confirmation is received? This question is particularly relevant when there's a delay between hiring and notification, raising issues about retroactive premium liability and access to benefits during the intervening period. A foundational Japanese Supreme Court decision from 1965 addressed this precise issue within the context of the Health Insurance Act (HIA) and the Employees' Pension Insurance Act (EPIA). The case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Confirmation of Invalidity of Health Insurance and Employees' Pension Insurance Insured Person Qualification Confirmation Disposition (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, Showa 38 (O) No. 223, June 18, 1965), established a key principle regarding the timing and effect of administrative confirmation of insured status.

Background: Delayed Notification and Retroactive Premiums

The appellant was Y Co., a company engaged in civil engineering and construction, established in January 1958. On May 1, 1958, Y Co. hired 14 individuals (referred to as A et al.). Under Japan's HIA and EPIA, employers meeting certain criteria (applicable workplaces, tekiyou jigyōsho) are required to enroll their eligible employees in these social insurance programs.

However, Y Co. did not submit the required notification (todokede) to the relevant administrative authority (at that time, the Prefectural Governor, G, acting for the insurer, the Government) regarding the employees' acquisition of insured status until July 19, 1958, more than two months after they started employment.

Following receipt of the notification, the Governor (G) issued an administrative disposition known as a "confirmation" (kakunin). This confirmation stated that the 14 employees had acquired insured person status under both HIA and EPIA retroactively, effective from May 1, 1958, the date they commenced employment. The formal notice of this confirmation, along with the employees' insurance cards, was delivered to Y Co. on August 18, 1958.

Based on this confirmation establishing eligibility from May 1, the local Social Insurance Branch Office subsequently assessed Y Co. for both employer and employee shares of HIA and EPIA premiums covering the period from May 1, 1958, through July 1958.

The Legal Challenge: Effective Date of Qualification

Y Co. contested the validity of the Governor's confirmation disposition, specifically challenging its retroactive effect to the date of employment (May 1). The company filed a lawsuit seeking a declaration that the disposition confirming qualification before the notification date (July 19) was invalid.

Y Co.'s core argument centered on the interpretation of the relevant provisions of the HIA and EPIA. They contended that:

- Confirmation Should Follow Notification: Since the administrative process of confirming qualification is triggered by the employer's notification, the effective date of qualification (and thus the start of premium liability) should logically be tied to the date of that notification, not the earlier date of hiring.

- Unfairness of Retroactive Liability without Benefits: It was unfair and unreasonable to impose retroactive premium liability on the employer (and implicitly the employees) for the period between hiring (May 1) and notification/confirmation (July/August), particularly because during that time, the employees had not yet received their insurance cards. Without the insurance card, accessing healthcare benefits under the HIA system "in kind" (genbutsu kyūfu – i.e., presenting the card at a clinic/hospital and paying only the co-payment) was practically difficult or impossible. They argued it was inequitable to demand premiums for a period when the corresponding insurance benefits were not readily accessible.

The company argued that the lower court's decision upholding the retroactive confirmation misinterpreted several articles of the HIA (including Articles 3(3), 8, 13, 17, 21-2, 44, 78, and related regulations) and corresponding EPIA provisions.

The Osaka District Court and the Osaka High Court both rejected Y Co.'s arguments, finding that qualification was acquired upon employment and the subsequent confirmation made this effective retroactively. Y Co. appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Retroactivity Upheld

The Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed Y Co.'s appeal, affirming the lower courts' interpretation and upholding the principle that administrative confirmation of social insurance eligibility under HIA and EPIA relates back to the actual date of employment.

1. Interpreting the Statutory Framework:

The Court acknowledged the seemingly dual structure within both the HIA and EPIA regarding qualification:

- Acquisition upon Employment: One set of provisions clearly states that an insured person acquires insured status (shikaku o shutoku suru) from the day they become employed at a covered workplace (HIA Art. 17, EPIA Art. 13(1) cited).

- Effectiveness upon Confirmation: Another set of provisions states that the acquisition of qualification takes effect (kōryoku o shōzuru) only upon confirmation (kakunin) by the insurer or the Prefectural Governor (HIA Art. 21-2(1), EPIA Art. 18(1) cited).

2. Reconciling the Provisions: Purpose and Function:

The Court explained the legislative rationale behind this two-part structure:

- Broad Coverage and Risk Pooling: The primary goal of these compulsory social insurance systems is to extend benefits broadly to the workforce, distribute the risks associated with illness, injury, old age, etc., rationally across a large pool, and prevent adverse selection (where only high-risk individuals might opt-in if enrollment were voluntary). To achieve these goals, the law adopts the principle that workers automatically acquire insured status (tōzen ni) from the day of employment at a covered workplace.

- Legal Certainty and Relationship Establishment: However, the acquisition of insured status creates significant legal relationships involving rights and obligations between the insurer (government), the insured employee, and the employer (regarding benefits, premiums, notifications, etc.). To ensure clarity and certainty in these relationships, the law makes the legal effectiveness of the automatically acquired qualification dependent on administrative confirmation.

- Confirmation as a Prerequisite for Assertion: Therefore, until the insurer/Governor issues the confirmation (based on employer notification, employee request, or ex officio action), the parties (employee, employer, insurer) cannot validly assert (yūkō ni shuchō shi enai) the rights and obligations stemming from the qualification acquisition. Confirmation serves as the official act that makes the underlying factual status legally cognizable and enforceable within the system.

3. Determining the Reference Date for Confirmation:

Critically, the Court addressed what the confirmation confirms. It rejected Y Co.'s argument that confirmation should be based on the date of notification or the date the confirmation itself is issued. Instead, the Court held:

- The confirmation procedure is intended to verify the fact of qualification acquisition according to the statutory criteria.

- Therefore, the confirmation must be based on the date the qualification was actually acquired, which the law specifies as the date of employment (shikaku shutoku no hi).

4. Retroactive Effect ("Relation Back"):

Combining these points, the Court concluded:

- Confirmation is based on the date of employment.

- Once confirmation is issued, its legal effect relates back (sokyū shite) to the date of qualification (the employment date).

- Consequently, all parties can assert the legal effects of the insurance relationship (including eligibility for benefits and liability for premiums) retrospectively from that date.

5. Conclusion:

The Court found that the lower court's judgment, which aligned with this interpretation, was correct. Y Co.'s argument (that the notification date should be the effective date) was deemed a "unique view" (dokuji no kenkai) inconsistent with the proper interpretation of the HIA and EPIA framework. The appeal was therefore dismissed.

Significance and Analysis

The 1965 Y Co. decision, though dealing with a specific point of statutory interpretation, established a fundamental principle governing Japan's main employee social insurance schemes, with lasting implications:

- Principle of Retroactive Effectiveness: The ruling cemented the principle that administrative confirmation of eligibility for Health Insurance and Employees' Pension Insurance relates back to the factual event triggering qualification – namely, the start of employment at a covered workplace. This means the legal relationship, including rights and duties (like premium payments), is deemed to exist from the beginning of employment, even if paperwork and administrative processing occur later.

- Balancing Compulsory Coverage and Administrative Order: The decision reflects a balancing act inherent in compulsory social insurance. Automatic qualification upon employment serves the public policy goals of broad coverage, risk pooling, and preventing gaps. The subsequent requirement of administrative confirmation serves the need for legal certainty, proper record-keeping, and formal establishment of the complex legal relationships between employee, employer, and insurer. The "relation back" doctrine bridges these two aspects.

- Premium Liability Starts with Employment: A direct consequence, and the central issue for the appellant, is that liability for insurance premiums (both employer and employee shares) commences from the date of employment, not from the later date of notification or confirmation. This underscores the importance for employers to comply promptly with their statutory duty to notify the authorities when hiring eligible employees, typically within 5 days (under applicable regulations). Delays can lead to the accumulation of significant retroactive premium obligations.

- Addressing the Benefit Access Issue: The appellant raised a valid practical concern: the difficulty for employees in accessing healthcare benefits "in kind" (genbutsu kyūfu – using an insurance card) during the period between employment and the issuance of the card following confirmation. While the Court upheld the retroactive premium liability, it did not need to delve deeply into this benefit access issue to resolve the case about the effective date of qualification. However, the underlying legal structure implies solutions exist:

- Cash Reimbursement (Ryōyōhi): As noted in commentary related to the case, employees who incur medical expenses during this retroactive period, before receiving their card, could generally apply for reimbursement of the paid amount (minus the standard co-payment) from the insurer after their qualification is confirmed, under the HIA's provisions for療養費 (ryōyōhi). This provides financial coverage, although it requires the employee to pay the full cost upfront, which could be a hardship.

- Modern Solutions: Recognizing potential practical issues, the system has evolved since 1965. Mechanisms like temporary "Certificates of Insured Person Qualification" (hoken-sha shikaku shōmeisho) were introduced to bridge the gap while waiting for the formal insurance card. More recently, the integration of health insurance information with Japan's "My Number" individual identification system allows for online eligibility verification (on-rain shikaku kakunin) at healthcare facilities. Provisions also exist for confirming eligibility through self-declaration if online verification fails. These aim to minimize practical barriers to accessing care immediately after employment begins.

Conclusion

The 1965 Supreme Court decision in the Y Co. case established a crucial interpretive principle for Japan's compulsory employee social insurance systems: while administrative confirmation is necessary to give legal effect to an employee's insured status, qualification is automatically acquired upon commencing employment at a covered workplace, and the confirmation's effect relates back to that date. This means premium liability begins with employment, not later notification. The ruling highlights the legal structure designed to achieve broad, automatic coverage while maintaining administrative order, and underscores the employer's responsibility for timely notification to ensure the smooth functioning of the system and minimize retroactive financial burdens. While practical challenges regarding benefit access during the initial employment period existed, subsequent administrative and technological developments have aimed to address these concerns within the framework established by this foundational ruling.

- Japan’s Supreme Court Upholds Compulsory National Health Insurance (1958)

- Student Disability Pension Gap: Why the Supreme Court Backed Voluntary Enrollment (2007)

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- Health Insurance – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- Using the My Number Card as a Health Insurance Card (オンライン資格確認)