When Does a Share Certificate Truly Become a "Share Certificate" in Japan? A Supreme Court Perspective

Judgment Date: November 16, 1965

Case: Action for Confirmation of Shareholder Status (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

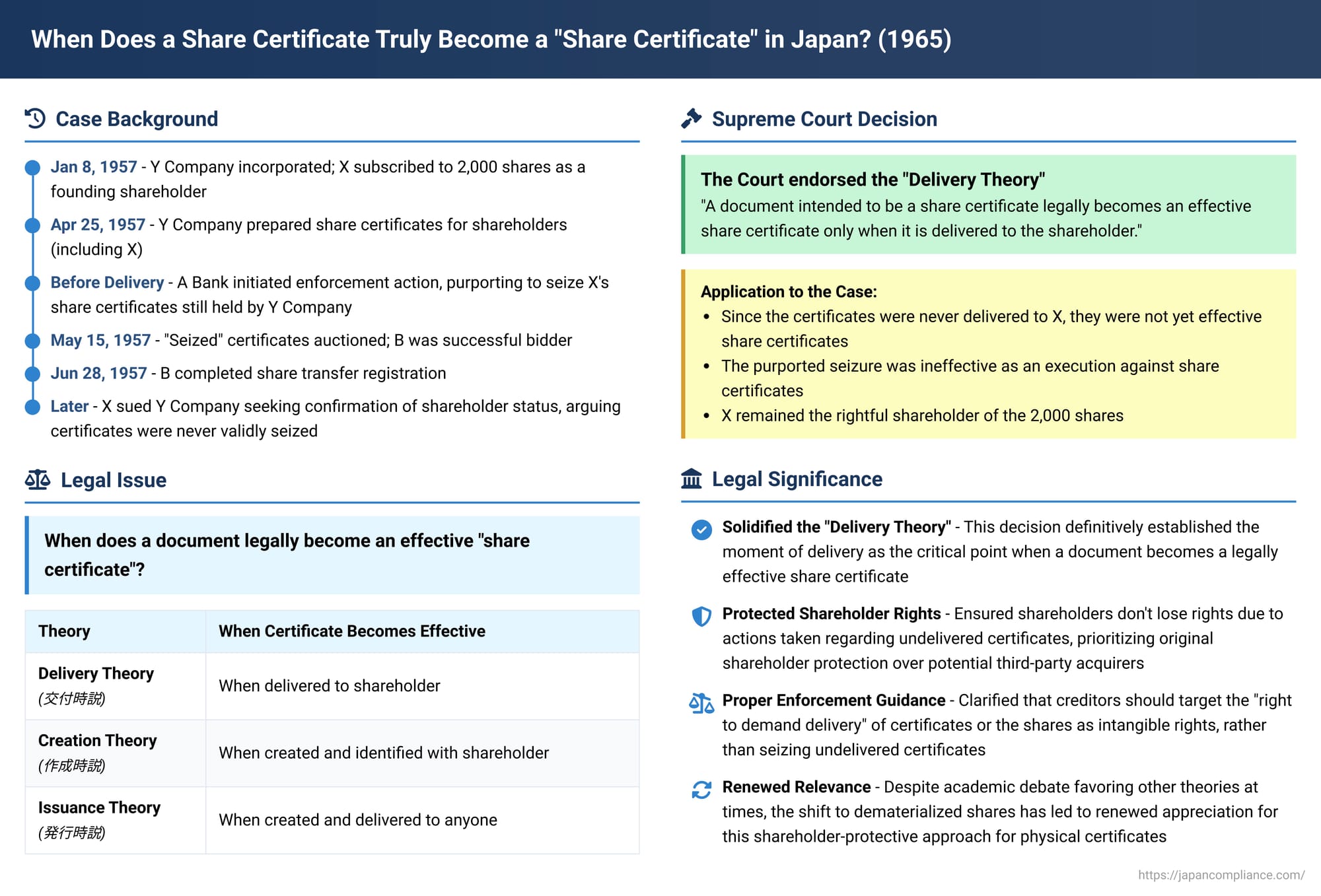

This 1965 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a foundational question in company law concerning physical share certificates: At what exact moment does a document prepared by a company to represent share ownership acquire the legal status and effect of an actual "share certificate"? The Court's clear answer emphasized the act of delivery to the shareholder as the determinative point.

Factual Background: A Shareholder, a Seizure, and Undelivered Certificates

The dispute involved Y Company and X, one of its founding shareholders.

- Share Acquisition: Y Company was incorporated on January 8, 1957. X had acted as an incorporator, subscribing to 2,000 shares around December 1956 and duly completing the payment for these shares, thereby establishing their status as a shareholder in Y Company.

- Preparation and Seizure of Certificates: On April 25, 1957, Y Company finalized its preparations for issuing physical share certificates to its shareholders. However, before Y Company could formally notify X or deliver these certificates, A Bank initiated an enforcement action against X. Based on an enforceable notarial deed it held against X, A Bank purported to seize X's share certificates. At this point, the physical documents intended for X were presumably still in Y Company's possession and had not yet been delivered to X.

- Auction and Subsequent Registration: Around May 15, 1957, the "seized" share certificates were put up for auction. B was the successful bidder for these certificates. Following the auction, on June 28, 1957, B completed the process of having the shares transferred to their name on Y Company's shareholder register.

- X's Legal Action: X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y Company, seeking a legal confirmation of their status as a shareholder owning 2,000 shares in the company. X's argument was that the seizure and subsequent auction were invalid because the documents seized had not yet become effective share certificates.

- Lower Court Rulings: The court of first instance found in favor of X. It held that the enforcement action was ineffective as an execution against valid share certificates because the certificates had not been lawfully delivered to X (the shareholder) before the seizure occurred. The High Court dismissed Y Company's appeal, prompting Y Company to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Delivery is Key

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Company's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions.

The Court's reasoning was direct and unambiguous:

- The term "issuance of a share certificate" as used in the Commercial Code (then Article 226, now largely corresponding to Article 215 of the current Company Law) refers to the act of the company delivering a document, which has been prepared in the form prescribed by law (then Article 225, now Company Law Article 216), to the shareholder.

- A document intended to be a share certificate legally becomes an effective share certificate only when it is delivered to the shareholder.

- Consequently, even if a company prepares such a document, it possesses no legal effect as a share certificate as long as it remains undelivered to the shareholder. The Supreme Court cited a 1922 Great Court of Cassation (the highest court at the time) judgment in support of this principle.

Analysis and Implications: The "Delivery Theory" Affirmed

This 1965 Supreme Court decision solidified the judiciary's long-standing position on when share certificates become legally operative, firmly establishing the "Delivery Theory" (交付時説 - kofu-ji setsu).

1. Competing Theories on Share Certificate Effectiveness:

While the Supreme Court was clear, academic discourse had explored various theories:

- Delivery Theory (交付時説 - kofu-ji setsu): The dominant view in early case law and supported by some scholars. The certificate gains legal effect upon delivery to the shareholder. Delivery isn't strictly limited to physical handover; constructive forms of delivery, such as sen'yu kaitei (where the transferor agrees to hold the item on behalf of the transferee), might suffice.

- Creation Theory (作成時説 - sakusei-ji setsu): For a significant period, this became a very influential, if not the majority, academic theory. It posited that a share certificate becomes legally effective when the company has created it and has definitively identified which specific certificate corresponds to which shareholder.

- Issuance Theory (発行時説 - hakko-ji setsu): A less common view, suggesting that a certificate becomes effective when the company creates it and, based on its own volition, delivers it to someone (not necessarily the shareholder).

2. Key Scenarios Where Timing of Effectiveness Matters:

The precise moment a share certificate gains legal effect is crucial in several contexts, primarily:

- Enforcement and Seizure Before Delivery to Shareholder (as in the present case):

- Under the Delivery Theory (adopted by the Court): An undelivered certificate is merely a piece of paper owned by the company and cannot be seized as an effective share certificate. Creditors wishing to execute against the shareholder's interest would typically need to target the shareholder's right to demand delivery of a share certificate from the company, or the shares themselves (as an intangible right). If the company then delivers the physical certificate to an enforcement officer pursuant to such an attachment, this delivery is considered equivalent to delivery to the shareholder, making the certificate effective and available for auction.

- Under the Creation Theory: The certificate, once created and identified by the company, would be considered effective even if still in the company's possession, making it directly seizable as a share certificate.

- The PDF commentary notes that while the specific enforcement methodology might differ based on the prevailing theory, the underlying debt enforcement is not rendered impossible by any of these theories.

- Theft or Loss of Certificates Before or During Delivery:

- This scenario, while less common in actual court cases, has been a focal point for academic discussions on balancing the interests of the original shareholder versus a subsequent bona fide acquirer of the lost or stolen certificate.

- Under the Delivery Theory: If an undelivered document is stolen or lost and ends up with a third party, that third party has acquired only a piece of paper, not a valid share certificate. The true shareholder can still demand the company issue a (new) valid certificate. The third party's recourse would typically be against their own transferor or based on other claims.

- Under the Creation Theory: If the certificate was deemed effective upon creation, a third party could potentially acquire good title to the shares through bona fide acquisition of this (already effective) certificate. In such a case, the original shareholder might lose their rights to those specific shares and would have to seek remedies such as damages from the company or other liable parties.

- It's generally not accepted in Japanese law that both the original shareholder and a bona fide acquirer could simultaneously hold valid rights to the same shares, primarily due to concerns about maintaining capital integrity and preventing shareholder dilution.

3. Criticisms and Defenses of the Theories:

The Creation Theory faced criticism because it could lead to a shareholder losing their rights due to events (like theft from the company's premises) entirely outside their control. Proponents of the Creation Theory sometimes argued that, unlike negotiable instruments where various theories co-exist, the unique nature of share certificates (where two valid certificates for the same underlying shares cannot exist) necessitated this approach to protect bona fide acquirers.

The practice of companies obtaining transit insurance when mailing new share certificates to shareholders was sometimes cited by Creation Theory supporters. However, others argued that insurance practices should follow legal principles, not dictate them. Furthermore, it's been pointed out that such insurance often covers the company's cost of reacquiring shares from the market to deliver to a shareholder whose original certificates went astray, a practice not strictly dependent on the Creation Theory being correct.

4. Modern Context: Dematerialization and Shifting Academic Views:

Despite the Supreme Court's clear 1965 affirmation of the Delivery Theory, the Creation Theory held considerable sway in academic circles for many years. However, the legal and practical landscape for shares in Japan has changed significantly:

- Dematerialization of Listed Shares: Since January 2009, shares of listed companies in Japan have been dematerialized, existing only in electronic book-entry form. For these shares, the concept of a physical share certificate's効力発生時期 (timing of effectiveness) is no longer relevant.

- Non-Issuance as the Norm: For unlisted companies, the default under the current Company Law is not to issue physical share certificates unless the company's articles of incorporation explicitly provide for their issuance (Company Law Art. 214). Even if a company is a "share certificate-issuing company," if it's not a public company, it doesn't have to issue a certificate unless requested by the shareholder (Company Law Art. 215(4)).

Given these changes, physical share certificates now circulate only in very limited contexts, primarily concerning shares in closely-held, non-public companies. This has led to a re-evaluation of the need to prioritize the protection of bona fide acquirers of physical certificates at the potential expense of the original, rightful shareholder. Consequently, there has been a noticeable trend towards increased academic support for the Supreme Court's long-standing Delivery Theory, as articulated in the 1965 judgment.

5. A Note on Statutory Interpretation:

The PDF commentary makes a technical observation that while the Supreme Court framed its decision as an interpretation of the statutory phrase "issuance of a share certificate" (then Commercial Code Art. 226; now Company Law Art. 215), the term "issue" in that context likely encompasses both the creation and delivery of the certificate, regardless of which theory one adopts for when legal effectiveness commences. The question of when a share certificate becomes legally effective is arguably a distinct conceptual issue from the simple definition of "issuance" in the statute.

Conclusion: Delivery Remains the Decisive Moment for Physical Share Certificates

The 1965 Supreme Court decision firmly established that a physical share certificate acquires its legal force and effect in Japan only upon its delivery to the shareholder. This "Delivery Theory" has significant implications for the validity of actions taken with respect to undelivered certificates, such as attempted seizures or transfers following loss or theft. While academic debate once strongly favored alternative theories, the profound changes in shareholding practices, particularly the widespread dematerialization of shares and the move towards non-issuance of physical certificates, have led to a renewed appreciation for the clarity and shareholder-protective aspects of this long-standing judicial precedent.