When Does a Lie Become a Crime? Japan's Supreme Court on Modern Fraud

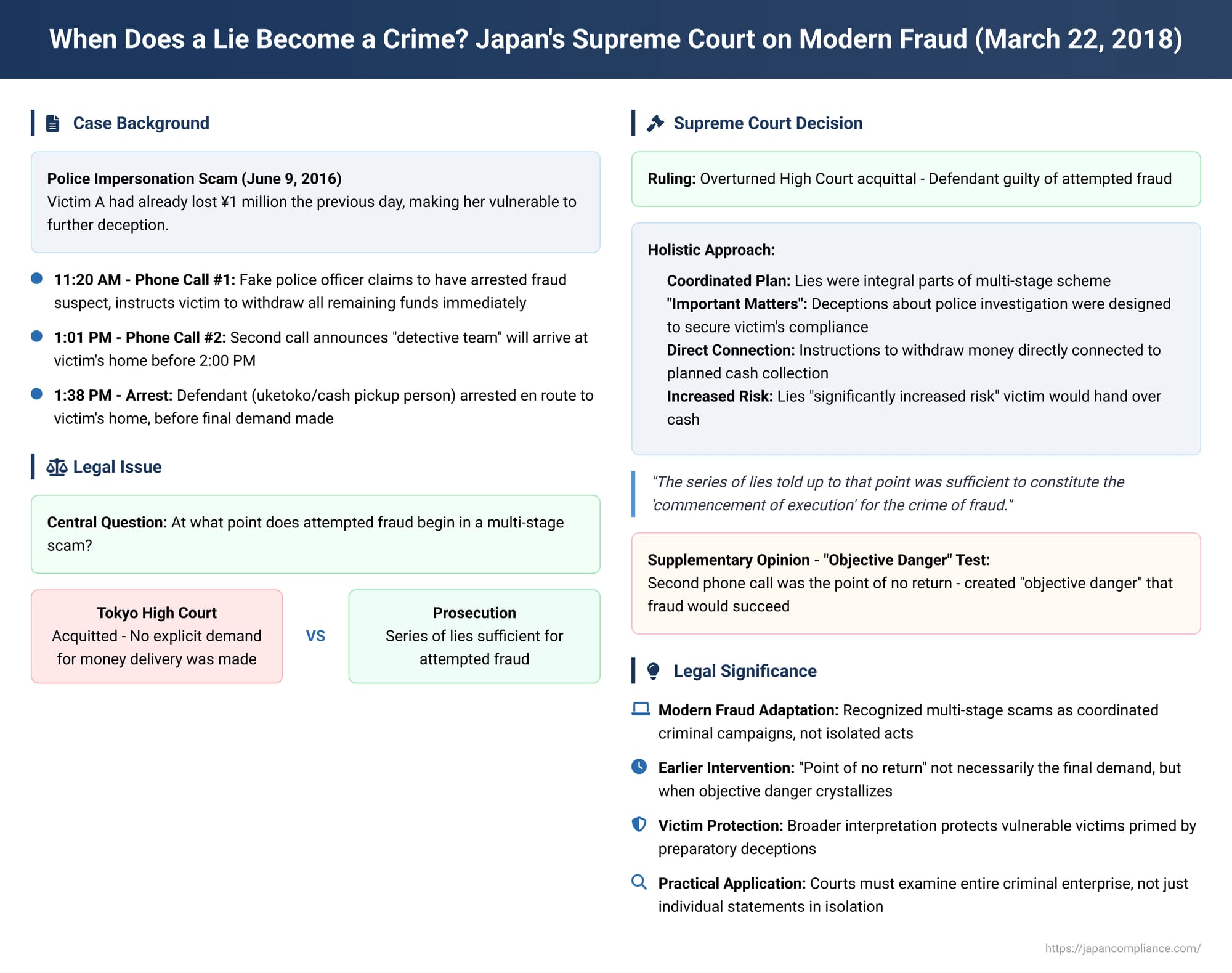

In an age of increasingly sophisticated and multi-stage scams, a fundamental legal question arises: at what precise moment does a liar cross the line from mere preparation to a punishable criminal attempt? Is it when they make the final demand for money? Or can the crime begin much earlier, in the carefully crafted lies that set the stage? On March 22, 2018, the Supreme Court of Japan tackled this very issue in a case involving a police impersonation scam, delivering a landmark ruling that adapted traditional legal principles to the realities of modern fraud.

The Anatomy of a Scam

The case centered on a victim, A, who was tragically already primed for deception. The day before the main events of the case, on June 8, 2016, she had been scammed out of one million yen by someone impersonating her nephew. This prior victimization made her particularly susceptible to the narrative that followed.

The next day, the criminal operation unfolded in a series of calculated steps:

- Phone Call #1 (11:20 AM): A person posing as a police officer called A. He claimed to have arrested a suspect in a fraud ring who had mentioned her name as a victim. He confirmed her previous day's loss and then gave a critical instruction: she needed to go to her bank immediately and withdraw all her remaining funds. This, he explained, was a necessary step for her to cooperate in recovering her lost one million yen.

- Phone Call #2 (1:01 PM): A second call came from the "police." The caller informed A that he was getting his team ready and would be heading to her home, expecting to arrive before 2:00 PM.

- The Courier: Meanwhile, the defendant in the case was activated. He was the "uketoko" (受け子), the cash pickup person. After receiving instructions and the victim's address, he was told to pose as a 29-year-old detective, go to A's home, and collect the money she had been instructed to withdraw.

- The Arrest: As the defendant made his way to the victim's residence, he was intercepted by actual police officers who had been monitoring the situation. He was arrested at 1:38 PM, before he could reach A's home and before anyone had made the final, explicit demand for the cash.

The Legal Conundrum: A Lie Without a Demand

The defendant was charged with attempted fraud. However, the Tokyo High Court, in a surprising decision, acquitted him. Its reasoning was simple and formalistic: the crime of fraud requires "deceiving a person" with the intent to have them deliver property. The High Court judges noted that while the callers had told A to withdraw her money, they had never actually asked her to hand it over. The words "give the money to the officer when he arrives" were never spoken. Since there was no explicit demand for delivery, the High Court concluded that the core act of deception had not occurred, and therefore, the crime had not yet commenced. It was all merely preparatory.

This acquittal set the stage for a critical review by the Supreme Court. Was the High Court's strict, literal interpretation correct? Or could the series of lies, even without a final demand, be enough to constitute a criminal attempt?

The Supreme Court’s Holistic Approach: The Entire Plan Matters

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the High Court's acquittal and reinstated the guilty verdict. The Court rejected a formalistic analysis of individual statements and instead took a holistic view of the entire criminal enterprise.

The Court's reasoning was built on a pragmatic assessment of the scam's design:

- A Coordinated Plan: The lies told in the two phone calls were not random. They were integral parts of a multi-stage plan specifically designed to culminate in the victim handing over cash to the defendant.

- Deception on "Important Matters": The content of the lies—that police had a suspect, that her cooperation was needed to recover prior losses, and that an officer was coming to her home—were "important matters." They were precisely the kinds of statements intended to form the basis of the victim's ultimate decision to part with her money.

- Direct Connection and Increased Risk: The Court found that the lies were "directly connected to the act of demanding delivery of the cash." By instructing the victim to withdraw her money and then announcing the imminent arrival of a "police officer," the perpetrators had paved the way for the final transfer. For a victim who had just been scammed, these lies would, in the Court's words, "significantly increase the risk" that she would immediately hand over the cash to the person at her door without further question.

The Supreme Court concluded that even though the explicit demand for delivery had not yet been made, the series of lies told up to that point was sufficient to constitute the "commencement of execution" for the crime of fraud.

A Sharper Lens: The Supplementary Opinion on "Close Connection" and "Objective Danger"

Adding further clarity, one of the justices provided a supplementary opinion that offered a more precise analytical framework, explicitly connecting this case to established legal doctrine. He referenced the "objective danger" standard from earlier landmark cases on criminal attempts (such as the 1970 rape case and the 2004 chloroform murder case).

This framework suggests a two-part test for commencement in situations that fall short of the final criminal act:

- Is the action closely connected to the core criminal act (in this case, the final deception and demand for money)?

- Does it create an objective danger that the crime will be successfully completed?

Applying this lens, the justice pinpointed the second phone call as the undeniable point of no return. While the first call might have been debatable, the second call—announcing the imminent arrival of the "officer"—was the key. This act was "closely connected" to the planned in-person demand for the money. Furthermore, it crystallized the "objective danger." The stage was set, the victim was primed and waiting with her cash, and the final actor was en route. The risk of the fraud's success was no longer merely potential; it had become acute and objectively high. At that moment, the crime of attempted fraud was complete.

Conclusion: Adapting Criminal Law to Modern Scams

The 2018 Supreme Court decision is a vital piece of jurisprudence for the digital age. It demonstrates a sophisticated understanding that modern fraud is often not a single deceptive act but a carefully orchestrated campaign of social engineering. The Court pragmatically adapted the traditional legal framework to this reality.

The ruling establishes that in a multi-stage scam, the "point of no return" is not necessarily the final demand. It is the moment when the preparatory lies have so effectively set the stage that they create a direct, significant, and objective risk of loss for the victim. By looking at the entirety of the criminal plan and its effect on the victim's state of mind, the Court ensured that the law remains equipped to hold perpetrators accountable, even when they are caught moments before the final, critical utterance.