When Does a Lawsuit Lose Its Purpose? A Look at Shareholder Resolution Challenges in Japan

Case: Action for Annulment of a Shareholders' Meeting Resolution and Action for Confirmation of Nullity of a Shareholders' Meeting Resolution

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of April 2, 1970

Case Number: (O) No. 1112 of 1969

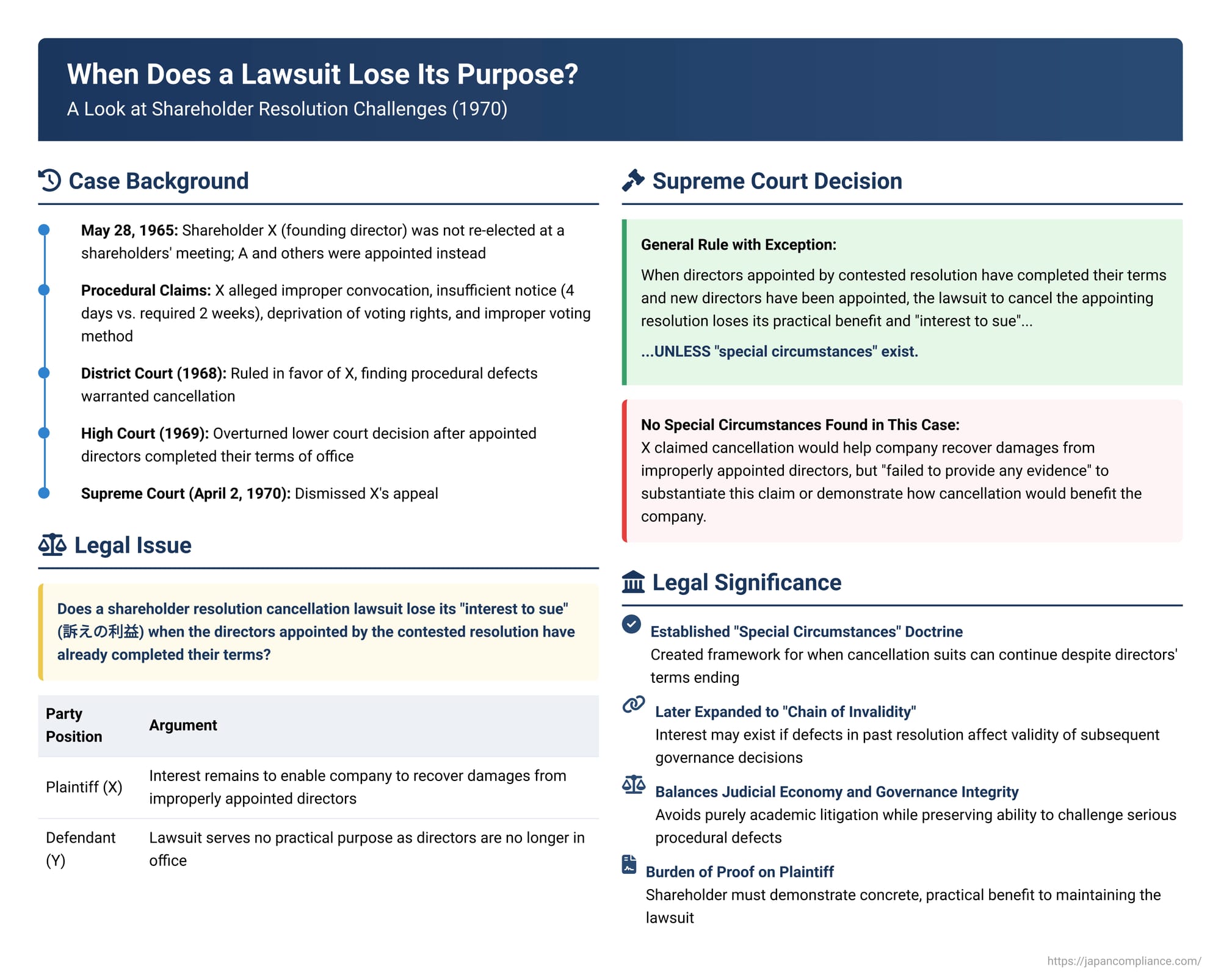

This case delves into a crucial aspect of corporate litigation: the "interest to sue" (referred to in Japanese as uttae no rieki), particularly in the context of challenging shareholder resolutions that appoint company directors. What happens when the directors appointed under a contested resolution have already left office? Does the lawsuit automatically become moot? The Supreme Court's decision on April 2, 1970, provides a foundational framework for answering this question, establishing that while the lawsuit might generally lose its practical benefit, "special circumstances" can keep the legal challenge alive.

Background of the Dispute

The appellant, X, was a shareholder and a founding director of Company Y. At a regular shareholders' meeting held on May 28, 1965 (referred to as "the Resolution"), X was not re-elected as a director. Instead, A and six others were appointed as directors, and B and one other individual were appointed as corporate auditors.

X filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the Resolution, alleging several procedural defects:

- Improper Convocation: The shareholders' meeting was convened without a prior resolution from the board of directors, which X argued violated Article 231 of the Commercial Code (the predecessor to Article 298, Paragraph 4 of the current Companies Act) and Company Y's own articles of incorporation.

- Insufficient Notice: The notice for the meeting was dispatched only four days before the meeting date, contravening Article 232, Paragraph 1 of the Commercial Code (now Article 299, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act), which stipulated a two-week notice period for such meetings.

- Deprivation of Voting Rights: Due to the short notice and improper convocation, X claimed that shareholders were deprived of the opportunity to request cumulative voting for the election of directors, a right designed to give minority shareholders a better chance at board representation.

- Improper Voting Method: The election resolution was allegedly passed using an open-ballot, multiple-entry method (where voters could list multiple candidates on a single ballot). X contended that this method violated the principle of one-share-one-vote enshrined in Article 241, Paragraph 1 of the Commercial Code (now Article 308, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act).

Journey Through the Lower Courts

The court of first instance (Fukuoka District Court, Amagi Branch, judgment dated January 26, 1968) largely agreed with X's assertions. It found that the claimed procedural flaws were indeed present and constituted valid grounds for cancelling the shareholders' resolution. Consequently, the court ruled in favor of X.

Company Y appealed this decision. The appellate court (Fukuoka High Court, judgment dated July 15, 1969) took a different view and overturned the first instance ruling. The High Court acknowledged the procedural defects but focused on a crucial development: by the time of its judgment, all the directors and auditors elected through the contested 1965 Resolution had already completed their terms of office as stipulated by Company Y's articles of incorporation. Furthermore, a subsequent shareholders' meeting held on May 21, 1967, had appointed new officers (who happened to be the same individuals re-elected).

The High Court reasoned that a lawsuit for the cancellation of a resolution is a type of "formative lawsuit" (a lawsuit seeking to create, change, or extinguish a legal right or status). It held that even such lawsuits can lose their "interest to sue" if, due to subsequent changes in circumstances, a judgment would yield no concrete practical benefit. Since the officers appointed by the 1965 Resolution were no longer in office, the High Court concluded that X's lawsuit to cancel their appointment had become devoid of any practical utility and dismissed X's claim. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment and Reasoning

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated April 2, 1970, dismissed X's appeal.

The Court began by affirming a general principle: a formative lawsuit, such as one seeking the cancellation of a shareholder resolution, typically maintains its "interest to sue" as long as the statutory requirements for bringing such an action are met. However, the Court immediately introduced a critical caveat: this interest can be extinguished by subsequent changes in circumstances.

Applying this to the specific context of a lawsuit challenging a resolution for the appointment of company officers, the Supreme Court laid down the following rule:

If, during the pendency of a suit to cancel a resolution appointing directors or other officers:

- All officers appointed by that resolution have completed their terms of office and retired; and

- A subsequent shareholders' meeting resolution has appointed new directors or officers;

Then, as a result, the officers whose appointments are being challenged are no longer in their positions. In such a scenario, the lawsuit to cancel the original appointing resolution is deemed to have lost its practical benefit and, consequently, the "interest to sue" is extinguished, unless special circumstances exist.

The Supreme Court then turned to whether such "special circumstances" were present in X's case. X argued that an interest in cancelling the 1965 Resolution still existed. The basis for this claim was that such cancellation was necessary to enable the company to recover damages it might have suffered due to actions taken by the improperly appointed directors during their tenure. X's contention implied that the lawsuit was being pursued for the ultimate benefit of Company Y.

The Supreme Court acknowledged that a suit to cancel a shareholders' resolution is not merely for the personal benefit of the plaintiff shareholder but also serves the interests of the company as a whole. However, the Court found X's argument lacking. While X claimed that the cancellation suit was for the company's benefit in terms of potential damage recovery, X had failed to provide any evidence to substantiate this claim or to demonstrate how the cancellation, at this late stage, would specifically aid in such recovery or otherwise benefit the company.

Therefore, in the absence of any proven "special circumstances," the Supreme Court concluded that the lawsuit indeed lacked the requisite "interest to sue." The appeal was dismissed, and the High Court's decision was upheld.

Deeper Dive: The "Interest to Sue" and "Special Circumstances"

The 1970 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark in Japanese corporate law for its articulation of the "special circumstances" exception to the general rule that the interest to sue is lost when challenged directors have already retired. While the Court in this specific case found no such circumstances, its acknowledgment that they could exist opened the door for further legal development.

What Constitutes "Special Circumstances"?

The judgment itself didn't provide an exhaustive list of what might qualify as "special circumstances." X's argument centered on recovering damages for the company due to the directors' actions while in office. The implication was that a formal cancellation of their appointment was a prerequisite or a facilitator for such recovery. However, the Court’s dismissal of this argument suggests that a mere assertion of potential corporate benefit is insufficient without concrete proof linking the cancellation to that benefit.

Subsequent legal scholarship and court decisions have explored the contours of "special circumstances." Some key considerations include:

- Retroactive Effect of Cancellation: A critical point in these discussions is the effect of a court order cancelling a shareholder resolution. Does it nullify the resolution from the moment it was passed (retroactively), or only from the moment of the court's judgment (prospectively)?

The prevailing view in Japanese law, now explicitly supported by Article 839 of the Companies Act, is that a judgment cancelling a shareholders' resolution has retroactive effect (sokyuukou). This means the resolution is treated as if it were void from the very beginning. This principle complicates the idea that a lawsuit automatically loses its benefit once directors retire. If their appointment was retroactively voided, it could, in theory, unravel actions taken under their authority or affect their legal status during their tenure.

This makes it more challenging to simply state that there is "no practical benefit" to cancellation once directors have retired. If the appointment is voided ab initio, there might still be legal consequences to address. - Impact on Subsequent Resolutions (The "Chain of Invalidity"): A significant development in understanding "special circumstances" came with later jurisprudence, notably a Supreme Court decision in Reiwa 2 (2020). This later case (though dealing with a cooperative association, its principles are considered applicable to stock corporations due to cross-referencing of company law provisions) suggested that an interest to sue for cancelling an earlier resolution (e.g., a director election) can persist if the defects in that earlier resolution taint or directly affect the validity of a subsequent resolution (e.g., the election of their successors).

Imagine a scenario:- Resolution A (first election) elects Director D. This resolution is flawed.

- Director D's term expires.

- Resolution B (second election) elects Director E, possibly under procedures influenced or presided over by those whose positions derive from the flawed Resolution A, or where the validity of Resolution B depends on the prior actions under Resolution A.

If a lawsuit challenging Resolution A is pending, and the invalidity of Resolution A would cascade to invalidate Resolution B (thus affecting the current board's legitimacy), then an interest to sue regarding Resolution A might be preserved. This is because the cancellation of Resolution A would have a direct, tangible impact on the current governance structure of the company. This "chain of invalidity" or "carry-over effect of defects" can constitute a "special circumstance."

- Arguments Typically Not Considered "Special Circumstances":

- Acts of Non-Directors: The argument that, upon cancellation, the directors' acts during their tenure should be treated as acts of non-directors, thus opening avenues for tort or unjust enrichment claims against them personally based on their lack of authority, is generally not favored as a standalone "special circumstance." The legal framework often provides for the validity of actions taken by de facto directors to protect third parties and ensure business continuity.

- Breach of Duty: If the core issue is that the directors breached their duties of care or loyalty, these are typically addressed through shareholder derivative lawsuits. The cancellation of their appointment resolution is not necessarily a prerequisite for such actions. The focus there is on their conduct as directors (even if defectively appointed), not solely on the validity of their appointment.

- Recovery of Remuneration: Seeking the return of salaries or bonuses paid to directors whose appointments are later cancelled is also a complex issue. If the directors performed their duties in good faith, courts are often reluctant to allow the company to claw back remuneration solely based on a procedural defect in their appointment, especially if the defect did not lead to direct financial harm equivalent to the remuneration. Arguments for recovery of remuneration as an "unjust enrichment" post-cancellation are not automatically accepted as a "special circumstance" justifying the continuation of the cancellation suit itself, particularly if services were rendered.

The Burden of Proof for "Special Circumstances"

A notable aspect of the 1970 Supreme Court judgment, and one that drew academic scrutiny, was its handling of the burden of proof for "special circumstances." The Court effectively placed this burden on the plaintiff (X). X argued for the company's benefit but "failed to provide any evidence."

This has been criticized because the "interest to sue" is generally considered a matter that the court should investigate ex officio (on its own initiative) as a prerequisite for allowing a lawsuit to proceed. Some scholars argued that if "special circumstances" relate to the very existence of the interest to sue, the court should proactively examine them, rather than placing the entire evidentiary burden on the plaintiff who is already trying to demonstrate the initial grounds for the lawsuit.

The judgment's phrasing also led some to believe it was imposing an unusually high bar for maintaining suits to cancel resolutions, particularly its focus on whether the suit was demonstrably "for the company's benefit" in a very specific, evidence-backed way.

Why Not Just Let the Cancellation Suit Proceed?

The rationale behind denying an "interest to sue" when directors have retired and been replaced, absent special circumstances, often revolves around judicial economy and the desire for legal stability. If a resolution's direct effects have ceased (i.e., the appointed individuals are no longer in office), allowing a lawsuit to continue to cancel that now-historic resolution might seem like an academic exercise with little real-world impact, unless specific ongoing consequences can be demonstrated. Companies need certainty in their governance, and endlessly litigating past appointments that have already run their course can be disruptive.

However, the "special circumstances" doctrine, especially as clarified by later cases concerning the "chain of invalidity," shows that the courts are also wary of allowing potentially serious procedural defects in past resolutions to go unaddressed if those defects could have a continuing impact on the current legitimacy or actions of the company's governance.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of April 2, 1970, is a pivotal decision in Japanese corporate law concerning the viability of lawsuits to cancel shareholder resolutions appointing directors. It establishes that while the lawsuit generally loses its practical purpose and "interest to sue" once the challenged directors have completed their terms and been replaced, this is not an absolute rule. The existence of "special circumstances" can preserve the lawsuit's validity.

The appellant in this particular case failed to convince the Court of such circumstances, primarily due to a lack of evidence supporting the claim that cancelling the resolution would concretely benefit the company. However, the door was left open. Subsequent legal interpretation has shown that these "special circumstances" can include situations where the defects in a past resolution have a cascading effect on the validity of current corporate governance structures.

This case underscores a tension: on one hand, the need for judicial efficiency and legal finality regarding past corporate actions; on the other, the importance of ensuring that corporate governance is founded on valid procedures and that unaddressed flaws do not perpetually undermine a company's legitimacy. The burden of demonstrating these "special circumstances" often falls on the plaintiff, requiring a clear showing of the ongoing, practical relevance of cancelling an otherwise dated resolution.