When Does a Cop's Illegal Act Become 'Abuse of Authority'? Japan's Wiretapping Case

The concept of "abuse of power" is central to the rule of law. We grant public officials special authority to perform their duties, but we also create laws to punish them when they misuse that power. But what is the legal definition of "abusing" one's authority? If a public official commits an illegal act as part of their job, but does so covertly, actively hiding their official status from everyone, can this still be the crime of "Abuse of Public Authority"? Or does that crime require the official to openly brandish their power to compel or disadvantage a citizen?

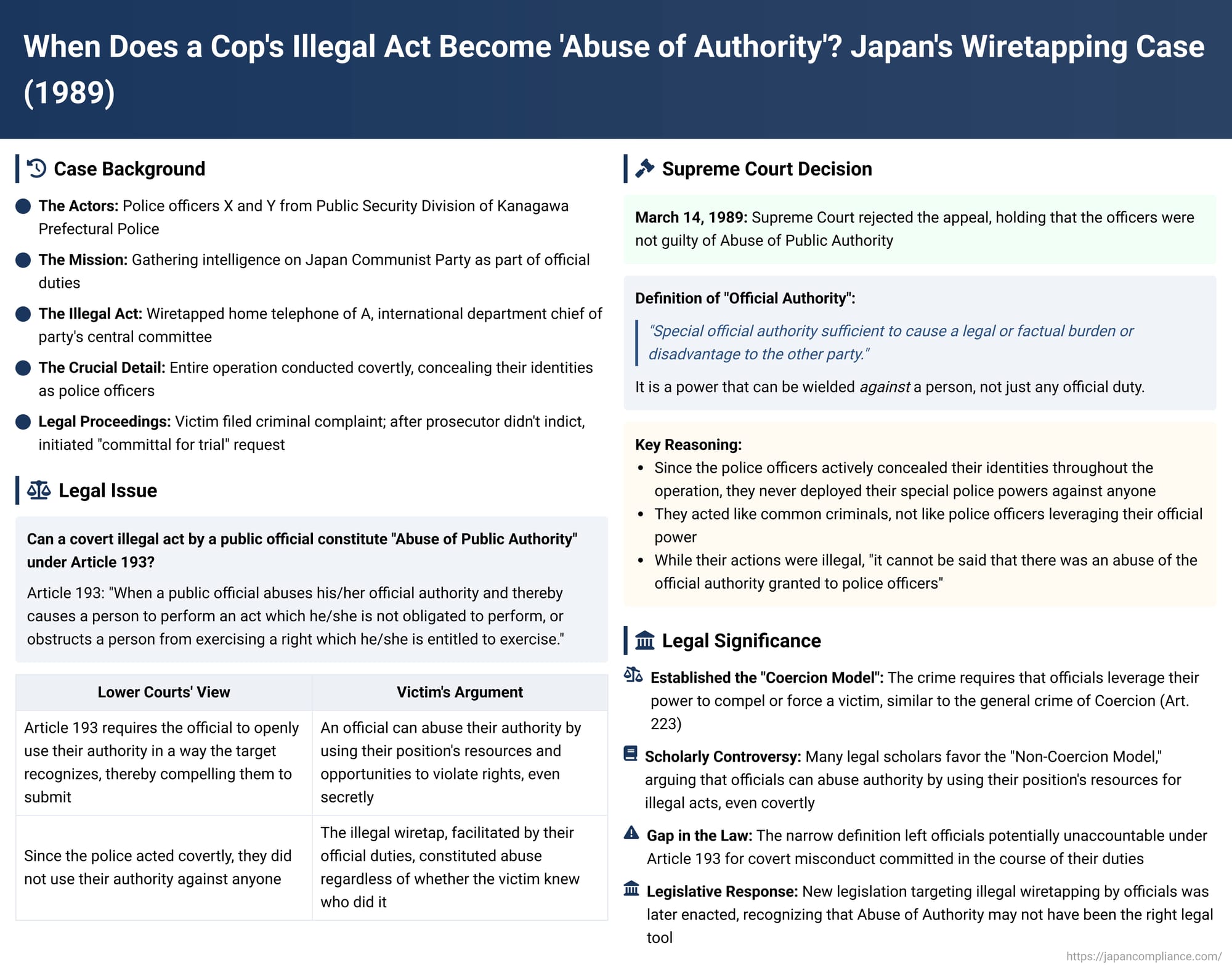

This fundamental question was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 14, 1989. The case, which arose from a secret police wiretap on a prominent political figure, provided a crucial, if controversial, definition of what it means to criminally abuse one's official authority.

The Facts: The Covert Wiretap

The case involved a clandestine police operation.

- The Actors: The subjects of the complaint were police officers X and Y, members of the Public Security Division 1 of the Kanagawa Prefectural Police.

- The Mission: As part of their official duties, they were tasked with gathering security intelligence on the Japan Communist Party.

- The Illegal Act: In a conspiracy with other officers, they illegally wiretapped the home telephone of A, who was the international department chief for the party's central committee.

- The Crucial Detail: The entire operation was conducted in secret. Recognizing that their actions were illegal under laws like the Telecommunications Business Act, the officers took great pains to conceal their identities. Throughout the process—from tampering with the phone lines to securing a listening post—they "took actions to disguise the fact that the act was being carried out by police officers from everyone at all times."

The Legal Question: Is a Secret Illegal Act an "Abuse of Authority"?

The victim, A, filed a criminal complaint against the unknown officers for, among other things, the crime of Abuse of Public Authority (Article 193 of the Penal Code). When the public prosecutor chose not to indict, A initiated a special legal proceeding (a "committal for trial" request) to have a court review the decision.

- The Law: Article 193 states that the crime is committed when a "public official abuses his/her official authority and thereby causes a person to perform an act which he/she is not obligated to perform, or obstructs a person from exercising a right which he/she is entitled to exercise."

- The Lower Courts' Rulings: Both the District and High Courts rejected A's request. They reasoned that the crime requires an official to wield their authority in a way that the target recognizes as an official act, thereby compelling them to submit. Since the police acted covertly, they did not use their authority against anyone in this manner. A then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No Authority Brandished, No Abuse

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal, agreeing with the lower courts' conclusion but clarifying the legal reasoning in a way that would become a key precedent. The Court held that the officers were not guilty of Abuse of Public Authority.

- "Official Authority" is a Special Kind of Power: The Court began by drawing a crucial distinction. The "official authority" (shokken) relevant to this crime is not an official's entire range of general duties. It is a "special official authority sufficient to cause a legal or factual burden or disadvantage to the other party." It is, in essence, a power that can be wielded against a person.

- Abuse Requires Using That Power: For the crime to be established, the illegal act must have been committed by abusing this special type of authority. The Court emphasized that an act could be part of an official's duties but not be an abuse of authority, while another act could be outside their duties but still constitute an abuse of authority.

- The Covert Action: Applying this to the facts, the Court reasoned that because the police officers actively concealed their identities and official status throughout the entire operation, they never deployed their special police powers against anyone. They acted like common criminals, not like police officers leveraging their official power.

- The Conclusion: Therefore, while their actions were illegal, "it cannot be said that there was an abuse of the official authority granted to police officers."

The Court also subtly corrected the lower courts, noting that their requirement for the victim to perceive the act as official was too narrow and could improperly exclude other forms of abuse of power.

Analysis: A Contentious Definition of "Abuse of Power"

This 1989 decision is the third in a trilogy of major Supreme Court rulings from the 1980s that shaped the modern understanding of Abuse of Public Authority in Japan. It firmly aligns the Court's position with what is sometimes called the "Coercion Model" of the crime.

- The "Coercion Model": This view sees Article 193 as being structurally similar to the general crime of Coercion (Art. 223), as both use the same language of making someone perform an act or obstructing a right. This model requires that the official leverage their power to compel or force the victim in some way. Since the wiretapping was covert and involved no compulsion, this model logically leads to an acquittal on this specific charge.

- The Scholarly Critique (The "Non-Coercion Model"): The ruling remains controversial and stands in contrast to the prevailing view among many legal scholars in Japan. This "Non-Coercion Model" argues that Abuse of Public Authority is a fundamentally different crime from Coercion and should not be limited to acts of compulsion.

- Proponents of this view argue that an official can abuse their authority by using the unique resources, access, and opportunities of their job to secretly violate a person's rights.

- From this perspective, the police officers were abusing their authority because their official duty of intelligence gathering gave them the means and motive to carry out the illegal wiretap, which harmed the victim's privacy rights regardless of whether he knew who was doing it.

- This view holds that the Court's narrow definition leaves a dangerous gap in the law, where officials can commit illegal acts in the course of their duties without being held accountable under this specific, serious statute.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1989 wiretapping decision established a clear, if narrow, definition for the crime of Abuse of Public Authority. It holds that for the crime to be committed, it is not enough for an official to simply commit an illegal act while on duty. The official must actively abuse the special, coercive powers of their office in a way that can be brought to bear against another person. A covert act where the official's status is completely hidden does not meet this standard.

While controversial, the ruling remains a critical precedent. It distinguishes between general misconduct by a public official and the particular evil the statute aims to punish: the leveraging of the state's unique power to compel, obstruct, or disadvantage a citizen. In the years since this case, new legislation specifically targeting illegal wiretapping by officials has been enacted, suggesting a recognition that while the act was illegal, Abuse of Public Authority may not have been the right legal tool to address it.