When Consent Isn't a Defense: Japan's Landmark Ruling on Injury for an Illegal Purpose

Decision Date: November 13, 1980

The principle of consent is a cornerstone of criminal law. In many situations, a victim's voluntary agreement to an act that would otherwise be criminal can negate the crime entirely. A boxer consents to being punched in the ring, a patient consents to a surgeon's scalpel, and a hockey player consents to the rough-and-tumble of the game. In these contexts, consent acts as a powerful legal shield. But are there limits to this principle? What happens when consent is given not for sport or for surgery, but as an integral part of a criminal scheme?

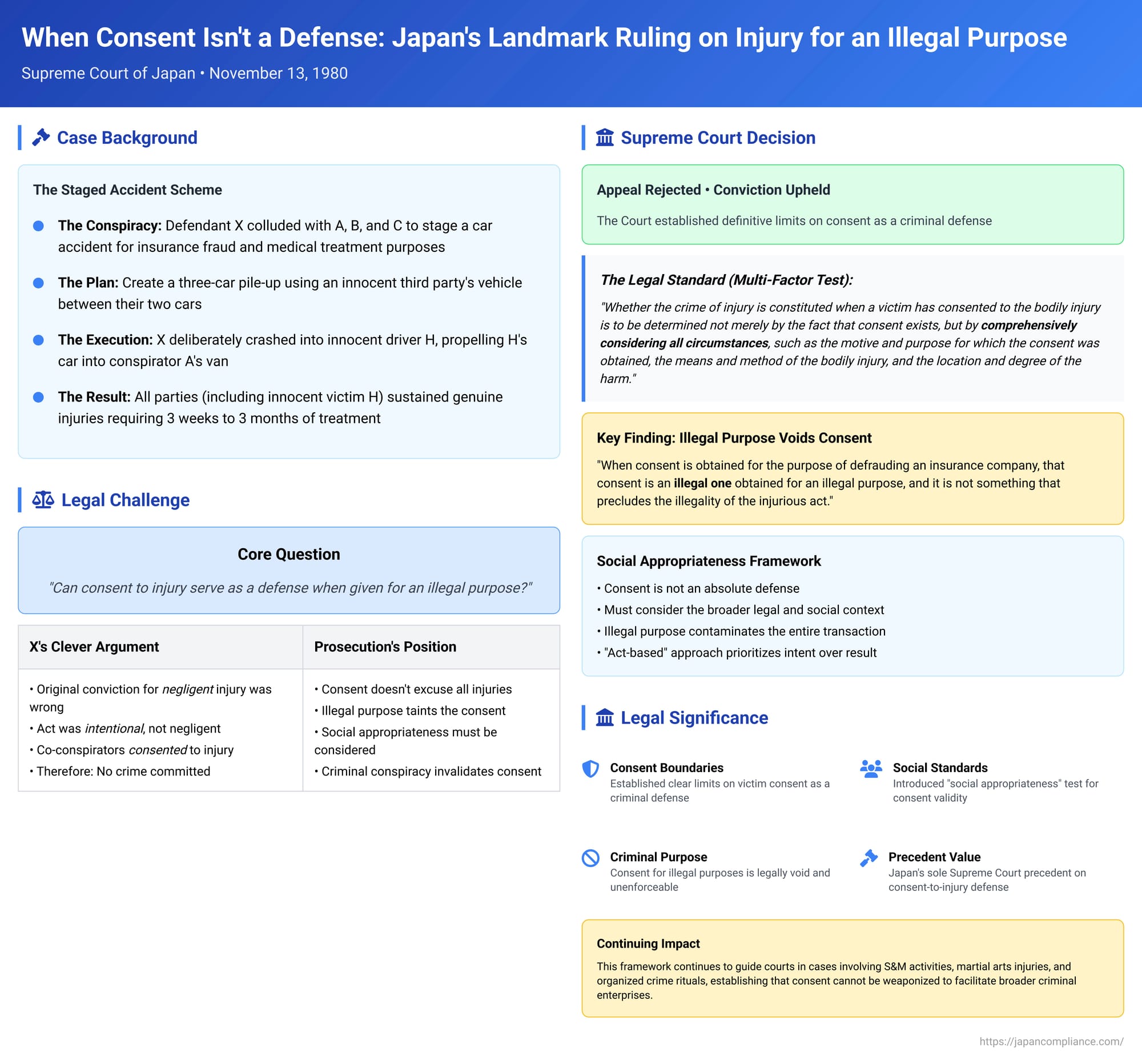

This complex question was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 13, 1980. The case, involving a meticulously staged car accident designed to defraud an insurance company, forced the court to define the boundaries of consent. In its ruling, the Court established that a victim's consent to being injured is not a magic wand that erases criminality; its validity is subject to a broader test of "social appropriateness," and consent given in the service of an illegal plot is no defense at all.

The Factual Background: The Staged Accident

The case began with a criminal conspiracy. The defendant, X, colluded with three others—A, B, and C—to stage a car accident. The scheme had a dual purpose: first, to fraudulently collect insurance money, and second, to provide B, who had a physical disability, with an opportunity to receive hospital treatment.

The plan was for X, driving his own car, to intentionally collide with a van driven by A and occupied by B and C. To enhance the illusion of a genuine accident, they schemed to create a three-car pile-up by having an unwitting third party's vehicle between their two cars.

The conspirators put their plan into action. At an intersection, A stopped his van for a red light. An innocent third-party driver, H, stopped his light vehicle behind A's van. The defendant, X, then pulled up and stopped behind H. At that moment, X deliberately accelerated and crashed his car into the rear of H's vehicle. The force of the impact propelled H's car forward, causing it to collide with the rear of A's van.

The staged collision resulted in genuine injuries. The innocent victim, H, along with the three conspirators A, B, and C, all suffered injuries, including cervical sprains, that required between three weeks and three months of medical treatment. (It was later noted that the injuries to the co-conspirators were, in fact, minor and did not require hospitalization.)

The Legal Path to the Supreme Court: A Clever Request for Retrial

Initially, the defendant, X, was prosecuted and convicted for Causing Injury through Professional Negligence and given a suspended prison sentence. However, the truth of the incident was later uncovered, and X was convicted and sentenced to prison for the insurance fraud.

This led X to make a clever legal maneuver. He filed for a retrial (saishin seikyū) of his original conviction for negligent injury. His argument was as follows:

- The conviction for negligent injury was factually incorrect, as the accident was a deliberate, intentional act.

- If the act was intentional, the proper charge would be the crime of intentional injury.

- However, with respect to his co-conspirators A, B, and C, they had all consented to being injured as part of the scheme.

- Therefore, he argued, he could not be guilty of negligent injury (because the act was intentional) nor of intentional injury (because his "victims" had consented). The logical conclusion, in his view, was that he should be acquitted of causing them any injury at all.

This argument forced the courts to confront the legal effect of consent given for a criminal purpose. The request for a retrial was denied, and the defendant appealed the denial all the way to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision on Consent

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal, and in doing so, delivered its sole and definitive precedent on the limits of consent as a defense to the crime of bodily injury. The Court's reasoning established a new, comprehensive framework for analysis.

The Core Legal Standard:

The Court declared that consent is not a simple, on-off switch for criminality. Instead, it articulated a multi-factor test:

"Whether the crime of injury is constituted when a victim has consented to the bodily injury is to be determined not merely by the fact that consent exists, but by comprehensively considering all circumstances, such as the motive and purpose for which the consent was obtained, the means and method of the bodily injury, and the location and degree of the harm."

This standard requires courts to look beyond the mere existence of consent and to conduct a holistic evaluation of the entire situation to determine if the act is, on the whole, socially acceptable.

Applying the Standard:

Applying this framework to the facts, the Court found the defendant's actions wholly unjustifiable. The key factor was the illegal purpose of the entire enterprise. The Court held:

"[W]hen, as in this case, for the purpose of defrauding an insurance company by pretending that it was a car accident caused by negligence, a person obtains the consent of a victim and intentionally causes injury by colliding with that person with one's own vehicle, that consent is an illegal one obtained in order to be used for the illegal purpose of defrauding an insurance company, and it is not something that precludes the illegality of the said injurious act."

In short, a consent given in the service of a crime is legally void. It cannot be used as a shield against criminal liability.

A Deeper Dive: The Doctrine of Victim's Consent in Japanese Law

This 1980 decision is profoundly important because it judicially defines the limits of a defense that is not fully detailed in the penal code. While the victim's right to self-determination is a respected principle, the Court made it clear that this right is not absolute.

The "Social Appropriateness" Framework:

The Court's approach in this case is a classic application of the legal concept of "social appropriateness" (shakaiteki sōtōsei). This overarching principle holds that for an act to be considered lawful, it must be justifiable from the viewpoint of the entire legal order. Under this framework, a victim's consent is not an independent, decisive factor that automatically negates a crime. Rather, it is one element—albeit a very important one—that must be weighed alongside all other circumstances to determine if the act as a whole is socially permissible. This is the same analytical framework the court has used in other landmark cases involving the limits of labor rights and press freedom.

The Primacy of an Unlawful Purpose:

A striking feature of the decision is its heavy, almost exclusive, reliance on the purpose of the act over the result. The Court did not delve deeply into the severity of the injuries or the specific dangers of the staged accident. The decisive element was the toxic, illegal purpose of insurance fraud. This illegal motive was seen as contaminating the entire transaction, rendering the consent offered by the co-conspirators legally ineffective. This reflects an "act-based" approach to wrongdoing, where the inherent character and intent of the act are paramount.

This approach aligns with a small but significant category of lower court cases, such as those involving yakuza-related finger-cutting rituals, where the socially abhorrent nature of the activity itself was enough to invalidate any consent given. This can be contrasted with the more common type of consent-to-injury cases, such as those involving injuries sustained during martial arts training or S&M activities. In those cases, where the purpose is not itself illegal, courts tend to focus more on the second factor: whether the act created an unacceptable risk of death or grievous bodily harm.

The case law, taken as a whole, suggests a sliding scale. When the purpose of an activity is legitimate, the lawfulness of any resulting injury depends primarily on the level of physical risk involved. But when the purpose of the activity is itself illegal or contrary to public morals, the lawfulness of the injury is determined primarily by the blameworthiness of that purpose.

Conclusion: Consent as a Shield, Not a Sword for Crime

The Supreme Court's 1980 ruling in the staged car accident case is a landmark decision that clearly defines the boundaries of consent in Japanese criminal law. It establishes that consent is not a trump card that can be played to justify any and all injuries. It is a conditional defense, subject to a broader analysis of social appropriateness.

Most importantly, the decision delivers an unambiguous message: the law will not honor consent that is given in furtherance of a criminal enterprise. The principle of self-determination cannot be weaponized to facilitate fraud or other crimes against third parties. By refusing to allow the defendant to use his co-conspirators' consent as a shield, the Court ensured that consent remains a defense for legitimate activities, not a sword for illegal ones.