When Collective Agreements Turn Unfavorable: The Asahi Fire (Ishido) Supreme Court Ruling

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of March 27, 1997 (Case No. 1995 (O) No. 1299: Claim for Confirmation of Status, etc.)

Appellant (Employee): X

Appellee (Employer): Y Company (Asahi Fire & Marine Insurance Co., Ltd.)

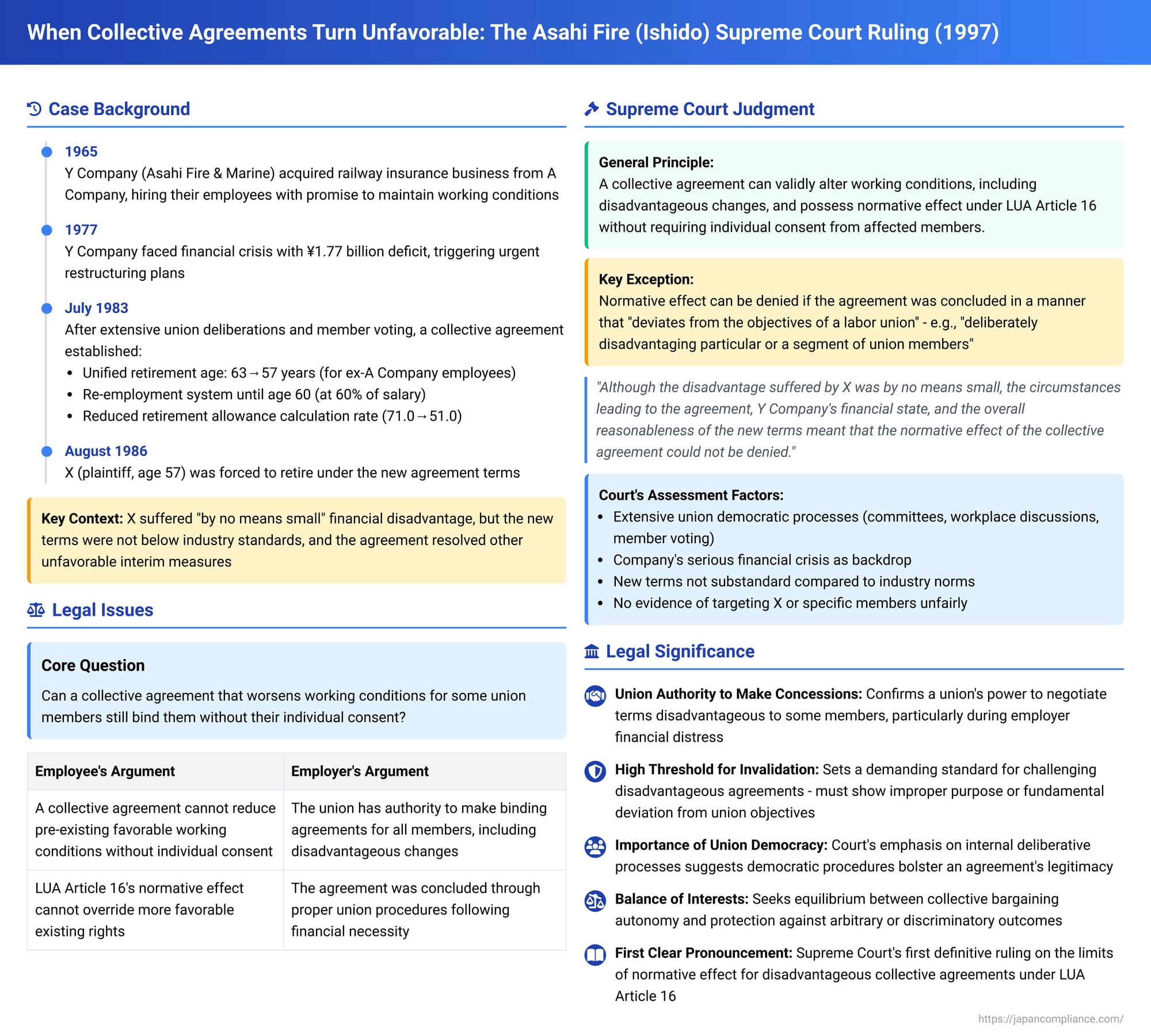

Collective bargaining agreements are fundamental instruments in shaping the landscape of employment conditions. In Japan, Article 16 of the Labor Union Act (LUA) grants these agreements a "normative effect," meaning their provisions regarding working conditions can directly override or supplement individual employment contracts. But what happens when a collective agreement, negotiated by a union, results in changes that are disadvantageous to some of its members? Can such an agreement still bind those adversely affected employees? The Supreme Court of Japan's judgment on March 27, 1997, in the Asahi Fire & Marine Insurance (Ishido) case, provides crucial answers to these questions, establishing important principles on the limits of a union's power to agree to unfavorable working conditions.

The Precipitating Crisis: Factual Background

The case involved Y Company, a non-life insurance provider, and X, one of its employees. The roots of the dispute lay in a historical disparity in working conditions.

- Historical Context: In 1965, Y Company acquired the railway insurance business from another firm, (Former) A Company. As part of this takeover, Y Company hired the employees who had been working in A Company's railway insurance department, with an undertaking to maintain their existing working conditions. Over the subsequent years, Y Company engaged in continuous negotiations with its employees' Union to standardize working conditions across its entire workforce. By 1972, most conditions, such as working hours, retirement allowance systems, and wage structures, had been unified. However, one significant difference persisted: the retirement age. Employees who had come from Former A Company's railway insurance department (like X) had a retirement age of 63, whereas other Y Company employees had a retirement age of 55.

- Financial Difficulties and Renewed Negotiations: In its fiscal year 1977, Y Company faced a severe financial crisis, reporting a substantial operating deficit of ¥1.77 billion. This precarious financial situation prompted the company to prioritize the long-standing issue of unifying the retirement age, coupled with a revision of the method for calculating retirement allowances, as a key measure for corporate restructuring. Intense negotiations with the Union ensued. During this period, from fiscal year 1979 until a new agreement on retirement allowances could be reached, an interim, "irregular" measure was put in place by mutual consent: any increases in the basic salary component of wages would not be factored into the calculation base for retirement allowances. This effectively froze a key component of the retirement pay calculation.

- The Disputed Collective Agreement (July 1983): After extensive internal deliberations—including discussions within its standing executive committee, national branch committees, workplace-level discussions among members, and member voting—the Union concluded a new collective bargaining agreement with Y Company in July 1983. The main provisions of this agreement were:

- Unified Retirement Age: The retirement age for all Y Company employees was set at 57.

- Re-employment System: A system was introduced allowing employees to be re-employed after reaching the new retirement age of 57, up to the age of 60, at a salary equivalent to approximately 60% of their regular employee pay.

- Reduced Retirement Allowance Calculation Rate: The formula for calculating retirement allowances was revised, resulting in a lower payout rate.

- Contextual Factors Considered by the Court:

- The previous 63-year retirement age for the ex-railway insurance staff was acknowledged as unusual for its time, stemming from the specific historical circumstance that this department had often hired individuals who had already retired from the national railway service after the age of 50.

- The new unified retirement age of 57 and the revised retirement allowance rates established by the 1983 collective agreement were found not to be substandard when compared to the prevailing norms within the Japanese non-life insurance industry at that time.

- Importantly, the conclusion of this new collective agreement led to the abolition of the aforementioned "irregular" and disadvantageous practice of freezing the base salary for retirement allowance calculations.

- Impact on Plaintiff X:

- At the time the 1983 collective agreement was signed, X was 53 years old.

- The new agreement meant his retirement age was reduced from 63 to 57. He would be required to retire on his 57th birthday in August 1986.

- The multiplier used to calculate his retirement allowance (applied to his final basic salary) would be significantly reduced from 71.0 to 51.0.

- The Supreme Court explicitly acknowledged that, even taking into account potential salary increases X might receive between 1983 and his new retirement age in 1986, the financial disadvantage he would suffer due to these changes was "by no means small."

X was subsequently treated as retired at age 57 under the terms of this new collective agreement. He challenged its validity, arguing that it could not lawfully alter his pre-existing, more favorable terms. He sought, among other things, a court declaration confirming his continued employment status (presumably until age 63) and his right to receive a retirement allowance calculated according to the previous, more generous system.

The Lower Courts' Rulings

The Kobe District Court (February 23, 1993) dismissed X's claim for confirmation of his employment status and rejected his claim concerning the retirement allowance under the old system. The Osaka High Court (February 14, 1995) also dismissed X's claims regarding the retirement allowance based on the prior system. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Upholding the Collective Agreement

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the validity and normative effect of the 1983 collective agreement, even though it was disadvantageous to X.

1. General Principle: Normative Effect of Disadvantageous Collective Agreements:

The Court began by affirming a general principle: a collective bargaining agreement can, as a rule, validly alter working conditions, and this includes changes that may be disadvantageous to some employees. Such an agreement can still possess "normative effect" under LUA Article 16, meaning its terms can directly modify the employment contracts of union members. The Court explicitly stated that the individual consent of each affected member, or specific authorization given by them to the union to agree to such adverse changes, is not a prerequisite for the collective agreement to bind them. In making this point, the Court referenced its earlier decision in the Asahi Fire (Takada) case, which had established a similar principle for the "general binding effect" of collective agreements under LUA Article 17.

2. The Key Test for Denying Normative Effect: "Deviation from Union Objectives":

While acknowledging the general binding nature of such agreements, the Supreme Court indicated that this is not absolute. The normative effect of a collective agreement that imposes disadvantages on members can be denied if the agreement was concluded in a manner that "deviates from the objectives of a labor union."

The Court provided an example of such a deviation: an agreement concluded with the specific aim of "deliberately disadvantaging particular or a segment of union members."

3. Application to X's Case:

The Supreme Court then meticulously applied this test to the circumstances surrounding the 1983 collective agreement:

- Process Leading to the Agreement: The Court took into account Y Company's severe financial crisis, the history of prolonged negotiations over unifying working conditions, and, significantly, the extensive internal democratic processes undertaken by the Union before concluding the agreement. These processes included deliberations in the Union's standing executive committee and national branch committees, as well as workplace-level discussions and voting by the general membership.

- Substance of the New Terms (Overall Reasonableness): While the changes were undeniably disadvantageous to X individually, the Court looked at the "overall reasonableness of the standards established by the agreement." It noted that the new retirement age of 57 and the revised retirement allowance levels were not out of line with industry standards at the time. Moreover, the agreement had the positive effect of resolving the "irregular" and unfavorable provisional measure that had frozen the base salary for retirement calculations.

- No Evidence of Improper Purpose or Discrimination: Crucially, the Supreme Court found no evidence to suggest that the 1983 collective agreement was concluded with the purpose of unfairly targeting X or any specific group of union members for detrimental treatment. There was no indication that the Union had acted in a way that "deviated from the objectives of a labor union."

Based on this comprehensive assessment, the Supreme Court concluded that although the disadvantage suffered by X was "by no means small," the circumstances leading to the agreement, Y Company's financial state, and the overall reasonableness of the new terms meant that the normative effect of the collective agreement could not be denied. The mere fact that X's conditions were worsened was not, in itself, sufficient to invalidate the agreement's binding force on him.

Significance and Implications of the Ishido Judgment

The Asahi Fire (Ishido) case is a landmark decision in Japanese labor law for several key reasons:

- Affirmation of Union's Authority to Make Concessions: The judgment clearly confirms that a labor union, in its capacity as the collective representative of its members, has the authority to negotiate and agree to terms that may be disadvantageous to some or all of its individual members. This power is particularly relevant in situations of employer financial distress, where concessions may be necessary for the company's survival and, ultimately, the preservation of jobs.

- High Threshold for Invalidating Disadvantageous Collective Agreements: The ruling establishes a high bar for challenging the normative effect of such collectively bargained agreements. An individual employee cannot simply point to the fact that their personal working conditions have worsened. To invalidate the agreement's effect on them, they would need to demonstrate something more egregious, such as the union acting with an improper discriminatory purpose or in a way that fundamentally deviates from its legitimate objectives as a representative body.

- Implicit Importance of Union Internal Democracy: While the Supreme Court did not make internal union procedural fairness the sole or explicit determinant of validity, its careful recitation of the Union's internal deliberative processes (committee discussions, workplace consultations, member voting) suggests that such democratic procedures can significantly bolster the legitimacy and defensibility of a collective agreement that includes concessions or disadvantageous changes. Prior to this judgment, some academic theories and lower court rulings had placed considerable emphasis on such procedural fairness within the union as a key factor in assessing the validity of disadvantageous agreements.

- "Deviation from Union Objectives" as the Limiting Standard: The standard articulated by the Court—that normative effect will be denied if the agreement was concluded in a manner that "deviates from the objectives of a labor union"—provides a theoretical limit on union authority. However, the judgment does not elaborate extensively on the precise legal basis or content of these "objectives," which leaves the standard somewhat open to interpretation in future cases. It seems to point towards situations involving an abuse of majority power to unfairly target a minority.

- Distinction from Unilateral Changes by Employer via Work Rules: It is important to distinguish this scenario from situations where an employer unilaterally changes working conditions to employees' detriment by amending its work rules. Such unilateral changes are subject to a different and generally stricter "reasonableness" test under Japanese labor law (as famously established in cases like the Shuhoku Bus case and later codified in the Labor Contract Act). The Asahi Fire (Ishido) case deals with changes made through a bilateral collective bargaining agreement. The law generally accords greater deference to terms agreed upon by two bargaining parties.

- Balancing Collective Bargaining Autonomy with Individual Protection: The judgment represents the Supreme Court's attempt to strike a balance between upholding the autonomy of unions and employers to determine working conditions through collective bargaining, and protecting individual employees from arbitrary, discriminatory, or grossly unfair outcomes resulting from that process.

The Evolving Landscape

The Asahi Fire (Ishido) judgment was the Supreme Court's first clear pronouncement on the limits of the normative effect of collectively bargained disadvantageous changes under LUA Article 16. Academic discussion continues regarding the appropriate criteria for judicial review of such agreements, including the relative weight to be given to procedural fairness within the union versus the substantive reasonableness of the outcomes, and how broadly to define the concept of "deviation from union objectives." For instance, the commentary raises the question of how to evaluate agreements that are disadvantageous to all members, not just a specific segment, and notes that the "deliberately disadvantaging particular members" standard is likely just one example of conduct that deviates from union objectives.

Conclusion

The Asahi Fire & Marine Insurance (Ishido) case is a pivotal decision in Japanese collective labor law. It firmly establishes that collective bargaining agreements can validly modify working conditions, even to the detriment of individual union members, and such agreements will generally have normative effect. However, this power is not unlimited. The Supreme Court has indicated that the normative force of such an agreement can be denied if it is demonstrated that the agreement was concluded for improper purposes, such as deliberately targeting certain members unfairly, or if it otherwise represents a clear deviation from the legitimate objectives of a labor union acting as a representative of its members. The case underscores the significant authority vested in the collective bargaining process while providing a backstop against egregious abuses of that authority. It highlights the importance of robust internal union democracy when difficult concessions are on the table.