Illegal Business Orders & Employee Damage Claims: Tokyo 2024 SES Fraud Case

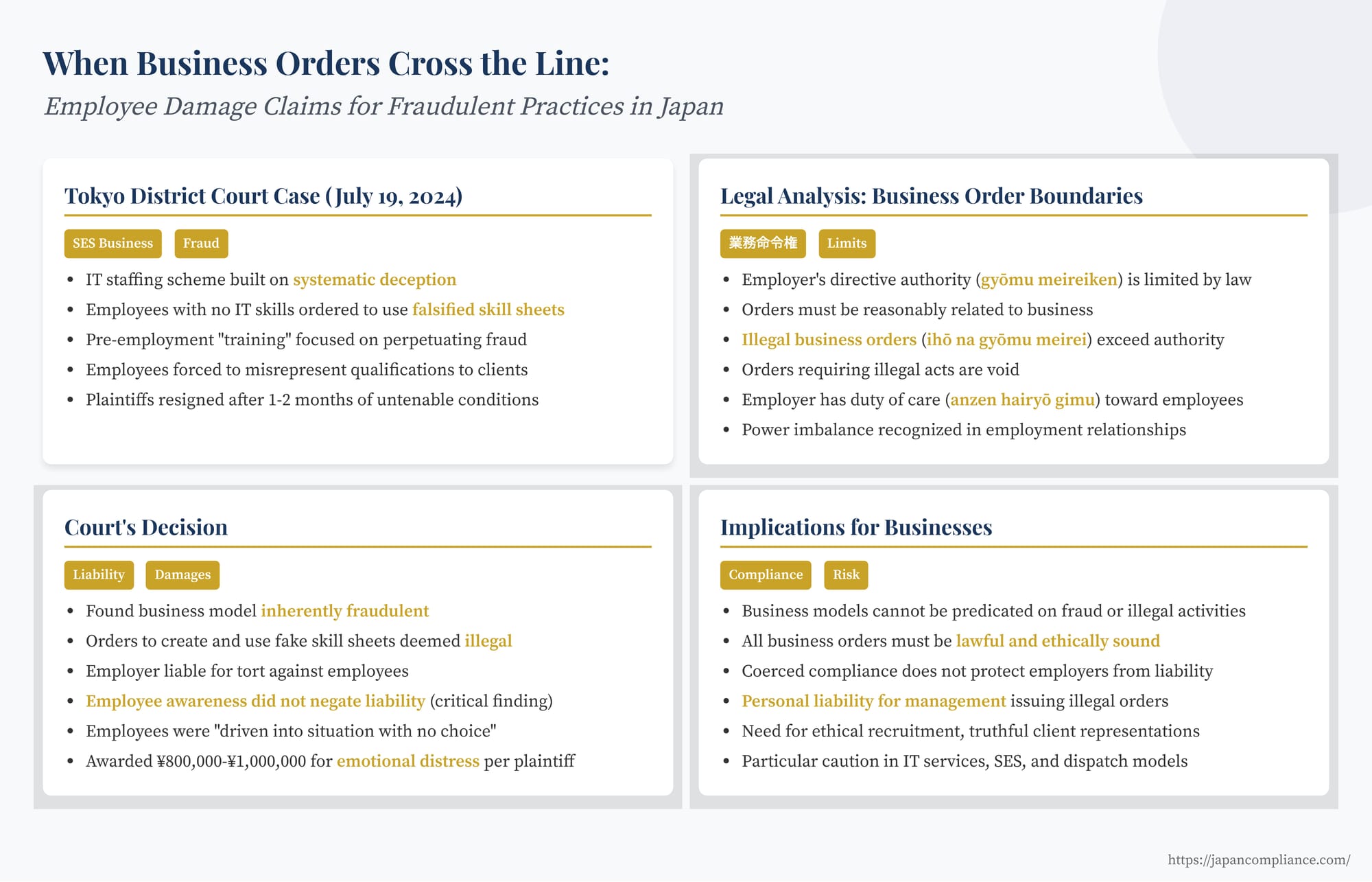

TL;DR: A 2024 Tokyo District Court held employers personally liable after ordering staff to falsify résumés in an SES fraud scheme. The ruling clarifies that illegal business orders breach the employer’s duty of care and trigger tort claims—even if employees later realise the wrongdoing.

Table of Contents

- The Case: A Business Model Built on Deception

- The Lawsuit: Claiming Damages for Coerced Participation

- The Court's Decision: Employer Liability Affirmed

- Legal Analysis: The Boundaries of Employer Directives

- Implications for Businesses Operating in Japan

- Conclusion: Upholding Employee Rights Against Unlawful Demands

The employment relationship in Japan, as in many countries, grants employers significant authority to direct the work of their employees through business orders (業務命令権 - gyōmu meireiken). This directive power is essential for managing operations and adapting to business needs. However, this authority is not absolute. A crucial question arises: What happens when an employer's orders require employees to engage in activities that are unethical, fraudulent, or outright illegal? Can employees who are compelled to participate in such wrongdoing hold their employer liable for the harm they suffer, even if they become aware of the illegality?

A recent decision by the Tokyo District Court on July 19, 2024 (Reiwa 6.7.19) provides significant insights into this complex issue. The case involved a System Engineering Service (SES) business model built on deception, where employees were ordered to misrepresent their skills to clients. The court's ruling underscores the limits of employer authority and affirms the rights of employees pressured into participating in fraudulent schemes, awarding substantial damages for the harm caused.

The Case: A Business Model Built on Deception

The lawsuit was brought by three former employees against the representatives of several related companies operating an SES business. The SES model, common in Japan's IT industry, involves dispatching engineers to work at client companies, often on a contract basis. While legitimate SES businesses exist, this particular operation had a foundationally fraudulent premise.

The Scheme: The companies recruited individuals with little to no IT engineering experience, often advertising positions that promised high earnings even for beginners. However, the core business strategy was to misrepresent these novice engineers as experienced professionals to secure contracts with client companies.

Fraudulent "Training": Before officially starting employment, two of the plaintiffs were required to enroll in and pay significant fees (hundreds of thousands of yen) for a "training school" run by affiliated entities. This training, however, reportedly focused not on genuine skill development but on perpetuating the fraud. Key components included:

- Creating falsified skill sheets (sukiru shīto) – resumes detailing non-existent experience and technical abilities.

- Making sales calls ("tele-appointments") to prospective client companies, using these fake credentials to solicit business.

(One plaintiff later managed to obtain a refund of the training fee after consulting a consumer protection center, highlighting the dubious nature of the program).

Illegal Business Orders: After completing the "training" and signing employment contracts (short-term, but automatically renewable, with monthly salaries specified), the plaintiffs were dispatched to various client companies. They received direct orders from their employer (or its representatives) to:

- Utilize the falsified skill sheets during client interactions.

- Participate in interviews with client companies, misrepresenting their experience and capabilities based on the fake skill sheets.

- Perform IT tasks (such as system design) at client sites for which they were fundamentally unqualified, maintaining the pretense of being experienced engineers.

Consequences for Employees: Predictably, the plaintiffs were unable to perform the work assigned to them at the client sites. They faced reprimands and difficult situations with the clients who believed they had hired skilled professionals. The stress and untenable working conditions led them to resign from their employment after only one to two months.

The Lawsuit: Claiming Damages for Coerced Participation

The plaintiffs sued the two individuals who effectively represented the network of companies involved in the SES business. Their claim was based on joint tort liability under Japan's Civil Code. They argued that the defendants were liable for damages resulting from two main actions:

- Fraudulent Inducement into Training: Inducing plaintiffs to pay for the worthless and fraudulent pre-employment training school.

- Illegal Business Orders: Issuing business orders that forced the plaintiffs to actively participate in the fraudulent scheme against client companies.

The plaintiffs sought compensation for the training fees (in one plaintiff's case) and, significantly, damages for emotional distress (慰謝料 - isharyō) caused by being recruited under false pretenses and then being compelled to engage in illegal and unethical conduct as part of their job duties.

The Court's Decision: Employer Liability Affirmed

The Tokyo District Court found in favor of the plaintiffs on several key points, establishing the liability of the company representatives.

1. Fraudulent Business and Training: The court unequivocally condemned the defendants' business model as inherently fraudulent, designed solely to profit by deceiving client companies. It found that the pre-employment "school" was not legitimate training but merely an instrument to facilitate this fraud, lacking any social appropriateness. Inducing the plaintiffs to pay for this "training" under the false belief they would acquire genuine IT skills constituted a fraudulent tort, and the court awarded damages equivalent to the non-refunded training fee.

2. Business Orders Deemed Illegal: This was the crux of the decision regarding the workplace conduct. The court held that the orders given to the plaintiffs – specifically, to create fake skill sheets, use them in client interactions (interviews, work performance), and essentially lie about their qualifications – were illegal business orders (ihō na gyōmu meirei).

The court reasoned that these orders mandated the employees to actively participate in the company's fraud against third-party clients. Forcing employees to carry out such illegal acts falls squarely outside the legitimate scope of an employer's right to issue business orders (gyōmu meireiken). Such orders are unlawful per se.

3. Employee Awareness Does Not Negate Employer Liability: The defendants likely argued, or it was considered, that the plaintiffs eventually became aware they were involved in a fraudulent scheme (the court inferred this likely happened by the time of client interviews). In many legal contexts, a participant's awareness or complicity can mitigate or negate liability claims.

However, the court made a critical distinction here. It ruled that the plaintiffs' later awareness did not absolve the defendants of liability for issuing the illegal orders in the first place. The court emphasized that the employees were placed in a vulnerable position ("driven into a situation where they had no choice but to follow instructions" - 指示に従わざるを得ない状況に追い込まれていた). The orders were fundamentally "against their will" (意思に反するもの - ishi ni hansuru mono). Therefore, the tortious nature of the orders themselves against the employees remained, regardless of the employees' subsequent, reluctant participation under duress.

4. Award of Damages for Emotional Distress: Recognizing the significant mental burden and ethical compromise forced upon the employees, the court awarded substantial damages for emotional distress (isharyō). The amounts ranged from 800,000 JPY to 1,000,000 JPY per plaintiff, in addition to other damages like unpaid wages and the training fee. This reflects a judicial acknowledgment of the severe harm caused by being coerced into illegal conduct as a condition of employment.

Legal Analysis: The Boundaries of Employer Directives

This decision touches upon fundamental principles of Japanese labor law regarding the employer's directive authority and the employee's rights.

The Right to Issue Business Orders (Gyōmu Meireiken): Japanese labor law generally recognizes a broad right for employers to issue orders necessary for business operations. This includes directives regarding work tasks, methods, assignments, and workplace conduct. However, this right is not unlimited. It is constrained by laws, collective agreements, work rules, and the employment contract itself. Critically, orders must be reasonably related to the business and cannot infringe upon the employee's fundamental rights or require them to perform illegal acts.

Illegal Business Orders (Ihō na Gyōmu Meirei): An order requiring an employee to commit an illegal act – such as fraud, perjury, environmental violations, or participating in anti-competitive conspiracies – is considered an illegal business order. Such an order exceeds the employer's legitimate authority and is legally void. Furthermore, compelling an employee to follow such an order can constitute a tort against the employee. This is because the employer has a fundamental duty of care towards its employees (安全配慮義務 - anzen hairyō gimu, rooted in Labor Contract Act Article 5 and Civil Code principles), which includes providing a safe and lawful working environment. Forcing participation in illegality breaches this duty.

The Significance of Employee Awareness: The court's treatment of the employees' awareness is particularly noteworthy. While acknowledging the plaintiffs likely knew about the fraud at some point, the court focused on the initial coercion and the power imbalance inherent in the employment relationship. It recognized that employees, especially early in their careers or in precarious employment situations, often feel immense pressure to comply with employer directives, even those they find unethical or illegal, for fear of losing their jobs. The court essentially held that the employer cannot use the employee's coerced compliance under duress as a shield against liability for issuing the illegal order that created the coercive situation. This distinguishes the situation from cases where an employee might willingly and proactively participate in wrongdoing from the outset.

Comparison with Other Cases: While cases affirming employer liability for harmful but perhaps not strictly illegal orders (like discriminatory transfers or harassment) exist, Japanese case law specifically addressing orders to commit illegal acts against third parties is scarce. This ruling provides a strong precedent that such orders constitute a direct harm to the employee forced to execute them. It resonates with a prior Ōtsu District Court decision (Reiwa 6.2.2) which found that orders forcing participation in disguised worker dispatch (gisō ukeoi), itself an illegal practice, could constitute harassment and tortious conduct against the employee.

Implications for Businesses Operating in Japan

This Tokyo District Court decision carries significant implications for employers in Japan, particularly those in sectors like IT services, consulting, or any field where employee qualifications and representations to clients are critical.

- Legitimacy of Business Models: Fundamentally, business models cannot be predicated on fraud or illegal activities targeting clients or third parties. This ruling shows that such practices create liability risks not only from wronged clients but also from employees forced to participate.

- Scrutiny of Business Orders: Employers must ensure that all business orders are lawful and ethically sound. Directives requiring employees to lie, falsify documents, misrepresent qualifications, or engage in any illegal act are invalid and expose the employer (and potentially managers) to direct liability claims from employees.

- Employee Coercion vs. Complicity: The ruling suggests that an employee's reluctant compliance under pressure, even with awareness of the wrongdoing, may not constitute true complicity that absolves the employer. The focus is on the employer's action in issuing the illegal order and creating the coercive environment. Clear policies encouraging employees to report illegal or unethical orders without fear of retaliation are crucial.

- Ethical Recruitment and Training: Deceptive recruitment practices and charging fees for non-existent or fraudulent training programs can independently create liability for fraud or related torts.

- Personal Liability for Management: The case targeted the company representatives directly, highlighting that individuals in management who devise, implement, or condone such illegal schemes can be held personally liable for the resulting damages to employees.

- SES and Dispatch Models: While the core issue was fraud, the context of an SES business highlights the need for careful compliance in industries utilizing dispatched or contracted workers, ensuring clear communication about roles, qualifications, and adherence to labor laws (including avoiding disguised dispatch).

Conclusion: Upholding Employee Rights Against Unlawful Demands

The July 2024 Tokyo District Court ruling serves as a stark reminder that the employer's power to direct work in Japan is subject to fundamental legal and ethical boundaries. While gyōmu meireiken grants broad authority, it does not extend to compelling employees to participate in fraudulent or illegal acts. Doing so constitutes a tort against the employee, exposing the employer and its representatives to potentially significant liability, including damages for emotional distress.

This decision reinforces that even if employees become aware of the impropriety, the initial act of issuing an illegal order within a coercive employment context remains a basis for employer liability. It underscores the importance of ethical business operations, lawful management directives, and respecting the rights and dignity of employees by not forcing them to compromise their integrity as a condition of their employment. For businesses operating in Japan, fostering a culture of compliance and ensuring the legality of all business orders is not just good practice, but a legal necessity to avoid significant liability risks.

- Share-Transfer Restrictions in Closely-Held Japanese Corporations

- Employee Dismissals in Japan: Membership vs. Job-Based Models

- Mind the Gap: Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Guidance on Illegal Business Orders (JP)

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/koyou_roudou/roudoukeizai/illegal_orders.html