When Avoided Payments Revive Guarantees: A 1973 Japanese Supreme Court Decision

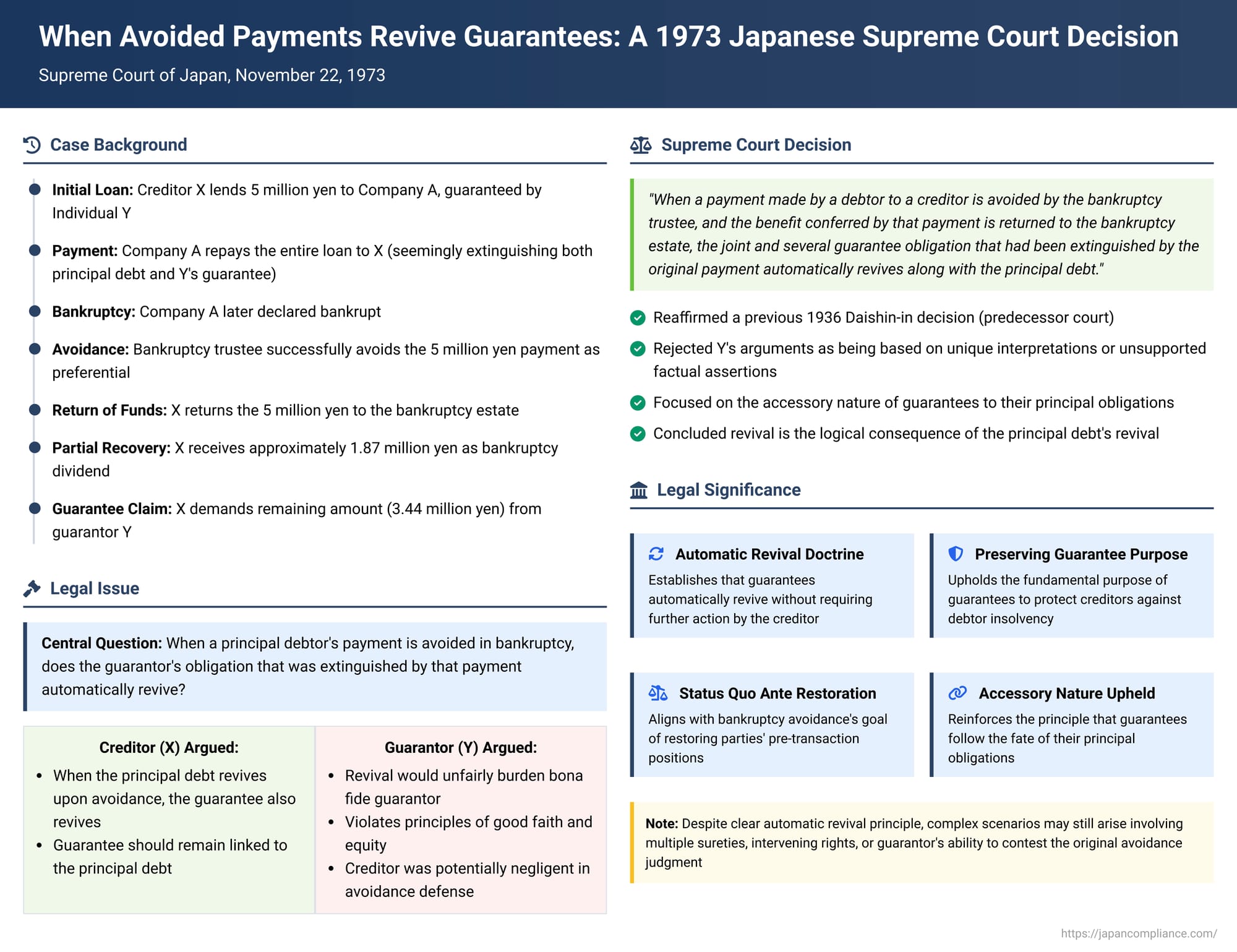

In the complex world of bankruptcy, a payment made by a debtor to a creditor shortly before insolvency can sometimes be "avoided" (否認 - hinin) by the bankruptcy trustee. This means the creditor must return the payment to the bankruptcy estate so it can be distributed more equitably among all creditors. But what happens if that original payment had also extinguished a guarantee provided by a third party for that debt? Does the guarantor get off the hook, or does their obligation spring back to life? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from November 22, 1973, addressed this precise issue, affirming that the guarantee indeed revives.

Factual Background: Payment, Avoidance, and a Claim Against the Guarantor

The case involved X, a creditor who had lent a total of 5 million yen to A Co. (the principal debtor). Y, an individual, had provided a joint and several guarantee (連帯保証債務 - rentai hoshō saimu) for A Co.'s debts to X.

Before the loan's maturity date, A Co. repaid the entire 5 million yen to X. This repayment naturally appeared to extinguish both A Co.'s principal debt and Y's accessory guarantee obligation. However, A Co. was subsequently declared bankrupt under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act.

A Co.'s appointed bankruptcy trustee later successfully sued X (the creditor) to avoid the 5 million yen repayment that A Co. had made. The court found that the repayment was an avoidable transaction (e.g., a preferential payment made during A Co.'s financial crisis), and this judgment became final. Consequently, X was required to return the 5 million yen, along with delay damages, to A Co.'s bankruptcy trustee.

Having returned the funds, X's original loan claim against A Co. was considered "revived" under the Bankruptcy Act. X filed this revived claim in A Co.'s bankruptcy proceedings and received a partial distribution (dividend) amounting to approximately 1.87 million yen.

With a significant portion of the original debt still outstanding, X then turned to the guarantor, Y. X filed a new lawsuit against Y, seeking payment of the remaining loan balance (approximately 3.44 million yen plus delay damages). X's argument was straightforward: since A Co.'s repayment was avoided and X's claim against A Co. revived, Y's joint and several guarantee obligation, which had been temporarily extinguished by the now-nullified payment, also revived.

Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled in favor of creditor X, agreeing that Y's guarantee obligation had indeed revived. Y, the guarantor, appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that:

- The relevant provision of the Bankruptcy Act (Article 79 of the old Act, now Article 169), which deals with the revival of a creditor's claim after they return an avoided payment, should not be interpreted so broadly as to cause loss to a bona fide third party (the guarantor, Y) in place of a beneficiary who received an avoidable payment (the creditor, X, who Y implied might have been "mala fide" in some sense).

- Reviving the guarantee obligation in these circumstances would violate fundamental principles of good faith and equity.

- Even if revival were generally possible, it should be denied if the creditor (X) was somehow negligent in the original avoidance lawsuit (e.g., by not adequately defending against the trustee's avoidance claim, thereby leading to the need to invoke the guarantee).

The Legal Issue: Does Avoidance of Principal Debt Payment Revive the Guarantee?

Under Japanese bankruptcy law (Article 169 of the current Act, similar to Article 79 of the old Act applicable in this case), when a bankruptcy trustee avoids an act by the bankrupt that had extinguished a debt (such as a payment), and the creditor who received that benefit returns it to the bankruptcy estate (or pays its value), the creditor's original claim against the bankrupt is deemed to revive. This ensures that the creditor is not left empty-handed after being forced to disgorge a payment.

The central question for the Supreme Court was whether this revival of the principal creditor's claim against the bankrupt debtor automatically leads to the revival of an accessory obligation, like a third-party guarantee, which had been extinguished by the same (now avoided) payment.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Guarantee "Automatically Revives"

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions and firmly establishing that the guarantee obligation does revive.

The Court's core holding was:

When a payment made by a debtor (who subsequently becomes bankrupt) to a creditor is avoided by the bankruptcy trustee, and the benefit conferred by that payment is returned to the bankruptcy estate, the joint and several guarantee obligation that had been extinguished by the original payment automatically revives along with the principal debt.

In its reasoning, the Supreme Court succinctly stated that this interpretation was "appropriate" and directly referenced a much earlier Daishin'in (the predecessor to the Supreme Court) judgment from July 31, 1936 (Showa 11 (O) No. 433). This 1936 precedent had reached a similar conclusion, effectively establishing a long-standing judicial view on the matter. The 1973 Supreme Court saw no reason to depart from this established jurisprudence and found no error in the High Court's judgment, which was to the same effect. Y's arguments were characterized as being based on unique interpretations or on factual assertions not supported by the lower court's findings. (The Court briefly addressed Y's first appeal point concerning X's alleged negligence in the avoidance suit, noting that the High Court had found no such negligence, and the Supreme Court saw no error in that factual determination).

The PDF commentary notes that the 1936 Daishin'in case cited by the Supreme Court was quite explicit, stating that when a payment is avoided and the funds are returned to the bankruptcy estate, then "joint debts, guarantee debts, or third-party security (物上担保 - butsujō tanpo) that had been extinguished by that payment are all self-evidently and automatically revived".

Rationale and Scholarly Support for Revival

The principle of "automatic revival" of guarantees in such situations is widely supported by legal scholars in Japan, based on several interconnected rationales:

- Purpose of Guarantees: A fundamental purpose of a guarantee is to provide security to a creditor against the risk of the principal debtor's default or insolvency. If a payment that seemed to satisfy the debt is later nullified by the bankruptcy trustee because it was, for example, a preferential payment made when the debtor was already insolvent, the very risk that the guarantee was intended to cover effectively rematerializes. Denying revival would frustrate this core purpose.

- Restoration of the Status Quo Ante: The avoidance of a transaction by a bankruptcy trustee is aimed at restoring the bankruptcy estate to the financial position it would have been in had the detrimental act not occurred. Correspondingly, the creditor who is forced to return the avoided payment is generally restored to their pre-payment position with respect to their claim against the bankrupt. The revival of the guarantee is a logical extension of this principle of restoring the original state of affairs.

- Guarantor's Assumed Risk: It is generally understood in legal theory that individuals or entities providing guarantees implicitly accept the risk that payments made by the principal debtor might, under certain circumstances (like a subsequent bankruptcy), be subject to avoidance. This potential for the revival of their guarantee obligation is part of the contingent liability they undertake.

- Consistency with the Accessory Nature of Guarantees: Guarantee obligations are accessory (付従性 - fujūsei) to the principal debt they secure. If the principal debt effectively revives from the creditor's perspective (both as a claim in the bankruptcy and as a basis for seeking recovery from other sources like a guarantor), then it is consistent with this accessory nature that the guarantee supporting it should also revive.

Regarding the guarantor's argument that the creditor who received an avoidable payment might have been "mala fide" (acting in bad faith), the PDF commentary points out that simply meeting the legal criteria for an avoidable payment (which might, for certain types of avoidance, involve the creditor's knowledge of the debtor's insolvency or suspension of payments) does not necessarily equate to the sort of egregious bad faith that would justify stripping the creditor of their right to rely on a revived guarantee. Creditors are generally expected to pursue the collection of debts owed to them.

Addressing Potential Complexities

While the core principle of revival is clearly affirmed, the PDF commentary accompanying this case highlights that its application can sometimes lead to complex situations, particularly concerning:

- Impact on Joint Debtors or Other Sureties: If, for example, one joint debtor (who later becomes bankrupt) makes a payment that extinguishes the debt, and another joint debtor, relying on this, makes a contribution payment to the first joint debtor, the subsequent avoidance of the original payment and revival of the full debt could unfairly burden the second joint debtor. Legal scholars have suggested that in such scenarios, the scope of avoidance or the extent of the revived liability might need to be limited to prevent such inequitable outcomes.

- Intervening Rights on Released Security: If a mortgage provided by a third-party surety was cancelled after the principal debt was paid, and then a new mortgage was registered on that same property in favor of a different creditor, the subsequent avoidance of the original payment and the "revival" of the first mortgage creates a conflict. How the priorities between the "revived" first mortgage and the new second mortgage are determined can be a complex issue, often involving considerations of bona fide acquisition and the effect of registration.

- Guarantor's Ability to Contest the Original Avoidance: A judgment in an avoidance lawsuit (typically between the bankruptcy trustee and the creditor who received the payment) generally determines the rights and obligations between those two parties. It does not automatically bind a third party like a guarantor, unless the guarantor was formally involved in that lawsuit (e.g., as an intervening party) or was given formal notice of the litigation. This means that when a creditor later sues a guarantor on the "revived" guarantee, the guarantor might still have the opportunity to argue that the original payment by the principal debtor was not actually avoidable in the first place, effectively re-litigating the grounds for avoidance. This is particularly relevant if the original creditor settled the avoidance claim with the trustee rather than litigating it to a final judgment.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1973 decision, by reaffirming the 1936 Daishin'in precedent, solidified the doctrine of "automatic revival" for guarantee obligations when a principal debtor's payment is successfully avoided by a bankruptcy trustee. This ruling ensures that a creditor, after being compelled to return a payment to the bankruptcy estate, is not unfairly deprived of the security that the guarantee was originally intended to provide. It reflects a legal policy that aims to restore the parties, as much as possible, to their positions prior to the avoided transaction, thereby upholding the efficacy of guarantee arrangements in the face of a principal debtor's insolvency. While the fundamental principle is clear, its application in multifaceted scenarios involving multiple sureties, intervening rights, or prior settlements can continue to present intricate legal challenges.