When an Ordinance Becomes a Challengable 'Administrative Act': Japan's Supreme Court on Daycare Abolition (Y City)

Judgment Date: November 26, 2009

Court: Supreme Court, First Petty Bench

Case Number: 2009 (Gyo-Hi) No. 75

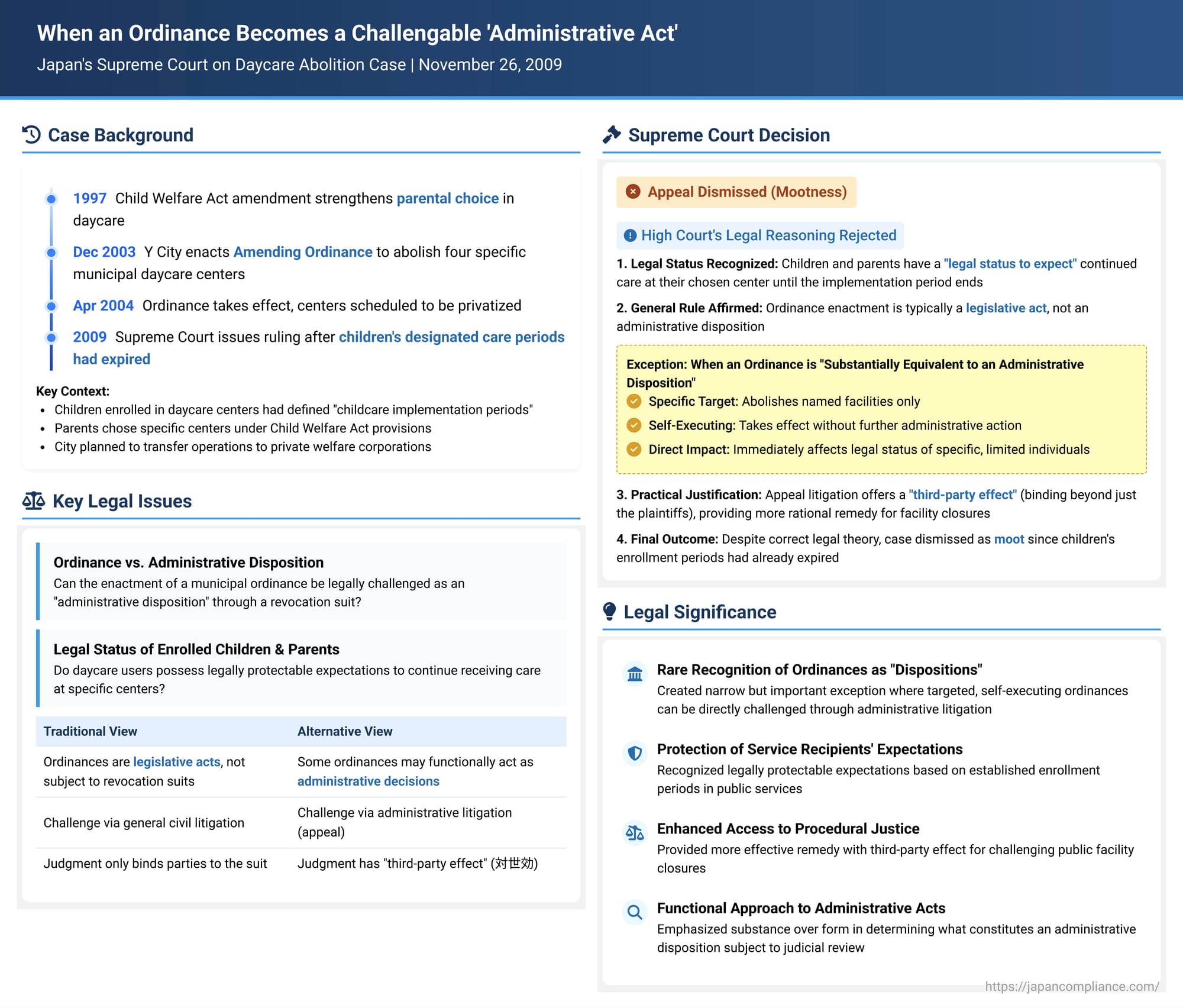

This article examines a notable 2009 Japanese Supreme Court decision that addressed the rare circumstances under which the enactment of a local ordinance can be treated as an "administrative disposition" (an act by an administrative agency) and thus become directly subject to judicial review through an appeal litigation (specifically, a revocation suit). The case arose from Y City's decision to abolish several municipal daycare centers and has important implications for understanding the legal recourse available to citizens affected by such local legislative actions.

Background: Public Daycare and Parental Choice in Japan

In Japan, the Child Welfare Act outlines the framework for childcare services. Municipalities are responsible for providing daycare for children who lack care due to reasons such as parental employment or illness. A significant amendment to the Child Welfare Act in 1997 strengthened the principle of parental choice. This means that when parents apply for a specific daycare center for their child, the municipality is generally obligated to provide care at that center if it has capacity, unless there are compelling reasons otherwise (such as overcapacity, which might necessitate a selection process). This change aimed to accommodate the diversifying needs of families, driven by factors like increased female participation in the workforce and varied employment patterns.

In Y City, the practice was that upon a child's admission to a municipal daycare center, a specific "period of childcare implementation" was designated, outlining the duration for which the service would be provided.

Facts of the Case

The appellants in this case were children enrolled in four specific municipal daycare centers operated by Y City, along with their parents or guardians (hereinafter referred to as "Xs"). These appellants had each been assigned a childcare implementation period at their respective centers.

Y City decided to "privatize" these four municipal daycare centers. In December 2003, the Y City Assembly enacted an ordinance (hereinafter "the Amending Ordinance") that amended the existing Yokohama City Daycare Center Ordinance. The sole effect of the Amending Ordinance was to remove these four specific daycare centers from the list of municipally operated facilities. This Amending Ordinance was promulgated on December 25, 2003, and was set to take effect on April 1, 2004, thereby legally abolishing the four centers as municipal entities. The plan was for private social welfare corporations to take over the operation of these facilities as licensed daycare centers.

In response, Xs initiated legal action, seeking the revocation of the act of enacting the Amending Ordinance. They argued that this legislative act unlawfully infringed upon their right to receive childcare services at their chosen municipal daycare centers for the duration of their agreed-upon enrollment periods.

Lower Court Ruling

The High Court, which heard the case before it reached the Supreme Court, dismissed Xs' suit. It held that the enactment of an ordinance is fundamentally a legislative act by the city assembly, not an "administrative disposition" by an executive agency. As such, the High Court concluded that the Amending Ordinance could not be the subject of an appeal litigation seeking its revocation.

The Supreme Court's Key Findings

The Supreme Court, while ultimately dismissing the appeal on grounds of mootness, disagreed with the High Court's reasoning concerning whether the enactment of the Amending Ordinance could be challenged as an administrative disposition.

1. Legal Status of Enrolled Children and Parents

The Court first established the nature of the rights held by the enrolled children and their parents:

- Under the Child Welfare Act, particularly following the 1997 amendments emphasizing parental choice, and considering Y City's practice of specifying a childcare implementation period upon admission, the relationship between the users and the municipal daycare is clearly defined.

- This relationship, based on parental selection and a set service period, is expected to continue until the period expires, unless lawfully terminated for reasons stipulated in the Child Welfare Act (e.g., under Article 33-4).

- Therefore, the Court found that children currently receiving care at a specific municipal daycare center, and their parents, possess a "legal status to expect to receive childcare at the said daycare center until the end of the childcare implementation period." This is a legally protectable expectation.

2. The Nature of the Amending Ordinance – An Exception to the General Rule

The Court then addressed whether the act of enacting the Amending Ordinance could be considered an administrative disposition:

- General Rule: The Court acknowledged the general principle that the enactment of an ordinance by a local assembly is a legislative function and, as such, is typically not an "administrative disposition" subject to an appeal litigation (which targets acts of administrative agencies). The abolition of public facilities like daycare centers is an administrative affair of the municipal mayor (under the Local Autonomy Act, Art. 149, Item 7) but requires an ordinance for its formal effect (Local Autonomy Act, Art. 244-2).

- Exception in This Specific Case: However, the Supreme Court determined that the Amending Ordinance in question presented exceptional characteristics:

- Its sole and exclusive content was the abolition of the four specifically named daycare centers. It was not a general regulation with broader applicability.

- It was self-executing. Upon its effective date, it directly brought about the abolition of these centers without requiring any subsequent administrative act or decision by an executive agency.

- It directly and immediately deprived a limited and specific group of individuals—namely, the children currently enrolled in those four centers and their parents—of their pre-existing legally protectable expectation to receive care at those specific facilities.

- Conclusion on "Administrative Disposition": Due to these specific features, the Supreme Court concluded that the act of enacting this particular Amending Ordinance could be considered "substantially equivalent to an administrative disposition" by an administrative agency. Therefore, it could, in principle, be the subject of an appeal litigation (specifically, a revocation suit).

3. Rationale for Allowing an Appeal Litigation

The Court provided a practical justification for allowing such a challenge through appeal litigation:

- If affected parties were restricted to other legal avenues, such as party lawsuits (tojisha sosho) or general civil lawsuits against the municipality to contest the ordinance's validity, any resulting judgments or injunctions would typically only bind the specific parties to that litigation.

- This could lead to practical difficulties for the municipality in managing the closure of the daycare centers, as a ruling in favor of one family might not apply to others. It could also lead to a multiplicity of lawsuits.

- In contrast, a judgment in an appeal litigation that revokes an administrative disposition (or an order suspending its execution) has a "third-party effect" (daisan-sha kou) under Article 32 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act, meaning it is effective with regard to third parties as well. Allowing the legality of such a specific, targeted ordinance-enacting act to be contested in a revocation suit, with its broader binding effect, was therefore deemed a more rational approach.

Ultimate Outcome of the Appeal: Dismissal due to Mootness

Despite establishing that the High Court had erred in its legal reasoning about the reviewability of the Amending Ordinance's enactment, the Supreme Court ultimately dismissed the appellants' (Xs') appeal.

The reason for this dismissal was mootness. By the time the Supreme Court issued its judgment in November 2009, the designated "childcare implementation periods" for all the appellant children at the respective daycare centers had already expired. Since the children were no longer entitled to receive care at these specific municipal facilities under their original enrollment terms, their legal interest in seeking the revocation of the Amending Ordinance (which had taken effect in April 2004) was deemed to have been extinguished.

Thus, while the High Court's reason for dismissing the case (that the ordinance enactment was not a disposition) was incorrect, its ultimate conclusion to not grant relief to the appellants was affirmed by the Supreme Court, albeit on the different ground that the claim had become moot.

Significance of the Case / Key Takeaways

The Y City Daycare Center Abolition Ordinance case is a landmark decision in Japanese administrative law, particularly concerning the justiciability of local ordinances:

- Ordinance Enactment as a "Disposition" (Narrow Exception): This case is highly significant as it represents a rare instance where the Supreme Court recognized that the legislative act of enacting a very specific type of ordinance can be treated as an administrative disposition, making it directly challengeable through an appeal litigation.

- Strict Conditions for the Exception: It is crucial to note that this exception is narrowly defined. For an ordinance's enactment to be considered a disposition, it must typically:

- Have a very specific and limited target (e.g., the abolition of particular, named public facilities rather than setting general rules).

- Be self-executing, meaning it directly causes the legal effect without needing further administrative action.

- Directly and immediately extinguish or alter the specific legal status or rights of an identifiable, limited group of individuals.

- Recognition of "Legally Protectable Expectations": The Court's explicit recognition of a "legal status to expect" continued daycare services based on the Child Welfare Act and enrollment practices demonstrates a willingness to protect reliance interests formed under existing legal and administrative frameworks.

- Procedural Avenue for Challenging Certain Ordinances: The ruling clarifies that, under these specific conditions, an appeal litigation (revocation suit) can be an appropriate procedural route for challenging local ordinances that have such direct, disposition-like impacts, offering the benefit of a judgment with third-party effect.

- Mootness in Administrative Litigation: The final outcome also serves as a practical reminder of the doctrine of mootness: if the legal interest that forms the basis of a lawsuit ceases to exist during the course of the litigation (e.g., due to the passage of time or changed circumstances), the court may dismiss the case even if there were initial legal errors in lower court decisions.

In conclusion, this Supreme Court judgment, while ultimately dismissing the specific claims due to mootness, established an important, albeit narrow, principle that certain legislative acts by local assemblies, when they possess the characteristics of a direct and targeted administrative disposition, can be subject to judicial review typically reserved for the actions of executive agencies. It highlights the judiciary's role in ensuring that even legislative actions at the local level are subject to legal scrutiny when they directly and immediately impinge upon the established legal positions of specific citizens.