When an Insider Skips the Rules: Japan's Landmark Case on Authority and Forgery

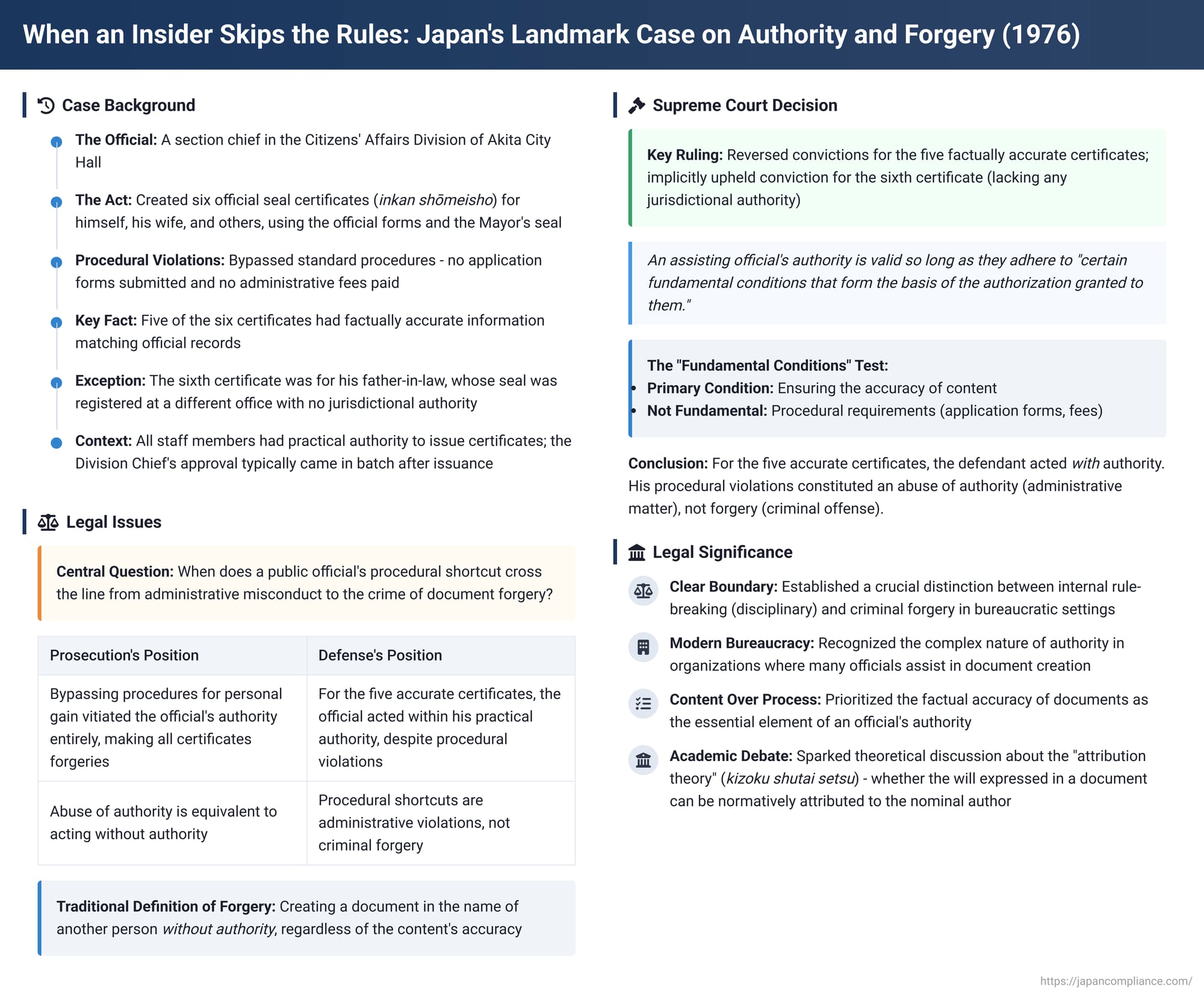

In the world of government and corporate bureaucracy, rules, procedures, and official seals are the bedrock of trust. Every official document is a testament to a process followed and an authority properly exercised. But what happens when an insider—a public official with the general responsibility for creating such documents—decides to take a shortcut for personal benefit? If they create a factually accurate and authentic-looking certificate but bypass all the required internal steps like filing an application or paying a fee, have they committed the serious crime of forgery? Or is it merely an internal disciplinary matter?

This question, which strikes at the heart of what it means to act "with authority," was the subject of a pivotal decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on May 6, 1976. The ruling, in a case involving a city hall official who created his own seal certificates, drew a sophisticated and enduring line between a punishable abuse of authority and the crime of forgery itself.

The Facts: The City Hall Official and the Seal Certificates

The case centered on a defendant who was a section chief in the Citizens' Affairs Division of the Akita City Hall.

- The Motive: Needing official seal certificates (inkan shōmeisho) for himself, his wife, and several associates to secure a personal loan for a new house, he decided to create them himself.

- The Act: In his office, the defendant used the official forms and the official seal of the Mayor of Akita to create six seal certificates.

- The Procedural Violations: He completely bypassed the standard procedure. He did not submit the required application forms for any of the certificates, nor did he pay the mandatory administrative fees.

- Factual Accuracy: Crucially, the content of five of the six certificates was entirely accurate. The names, addresses, and seal impressions on the documents perfectly matched the official records on file. Had a proper application been submitted for these five individuals, the certificates would have been issued as a matter of course.

- The Unauthorized Certificate: The sixth certificate, however, was for his father-in-law, whose seal was registered at a different branch office. The main city hall, where the defendant worked, had no authority to issue a certificate for that registration under any circumstances.

- The Context of Authority: While the formal regulations stated that issuing seal certificates was the exclusive purview of the Division Chief, the actual practice at the city hall was different. The Division Chief's approval was typically given in a batch after the certificates had already been issued—often on the following morning. By custom and practice, all staff members of the Citizens' Affairs Division, including the defendant, had the general authority to perform the tasks involved in creating and issuing these certificates.

The Legal Question: Abuse of Authority or Outright Forgery?

The lower courts convicted the defendant of forgery for all six certificates. Their reasoning was that by intentionally violating the established procedures for personal gain, he was "abusing his authority" (kengen no ran'yō). They held that this abuse was so severe that it vitiated his authority entirely, meaning he acted without authority and was therefore guilty of forgery. The defendant appealed, arguing that for the five accurate certificates, he was acting within the scope of his practical authority, even if he bent the rules.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Distinction

In a groundbreaking decision, the Supreme Court reversed the convictions related to the five factually accurate certificates. (It implicitly upheld the conviction for the sixth certificate, which was clearly created without any jurisdictional authority). The Court laid out a new, nuanced framework for assessing the authority of "assisting officials" in a modern bureaucracy.

- The Definition of Forgery: The Court began by reaffirming the traditional, "formalist" definition of forgery in Japanese law: the crime is committed when a person without authority creates a document in the name of another. It is a crime against the authenticity of authorship, not necessarily the truthfulness of the content.

- The Authority of an "Assisting Official": The Court recognized that in a modern bureaucracy, "authority" is not confined to the single person whose name is on the document (e.g., the Mayor) or their direct delegate (daiketsu-sha). It extends to "assisting officials" (hojo-sha)—like the defendant—who are empowered to create documents as part of their duties.

- The "Fundamental Conditions" of Authority: The Court then introduced its critical innovation. It ruled that an assistant's authority is valid only so long as they adhere to the "certain fundamental conditions that form the basis of the authorization granted to them." The most important of these conditions, the Court specified, is "ensuring the accuracy of the content."

- Applying the Test:

- The five certificates in question were factually accurate. The defendant had therefore fulfilled the most fundamental condition of his authority.

- The procedural shortcuts—skipping the application form and fee—were deemed not fundamental. The Court reasoned that the application's main purpose is to ensure accuracy (which was not an issue here), and the fee's purpose is to secure city revenue, not to act as a precondition for the document's validity.

- The Conclusion: For the five accurate documents, the defendant acted with authority. His procedural violations constituted an abuse of authority, a matter for internal disciplinary action, but not the crime of forgery.

Analysis: A Pragmatic Solution to a Formalist Problem

The Supreme Court's 1976 decision was a significant departure from older, stricter precedents and represented a pragmatic adaptation of the law to the realities of modern bureaucratic life.

- The Theoretical Challenge: The ruling has been a subject of intense academic debate. The core criticism is that by making the existence of "authority" dependent on the "accuracy of the content," the Court appeared to mix the formal concept of authorship with the substantive concept of truthfulness. This seems to contradict the very "formalism" that underpins Japanese forgery law.

- Alternative Frameworks: To resolve this apparent contradiction, legal scholars have proposed alternative ways of understanding the decision's logic. One influential view is the "attribution theory" (kizoku shutai setsu). This theory asks whether the will expressed in the document can be normatively "attributed" to the named author. In this view, the assistant's authority holds as long as the creation process guarantees that the final document reflects the will of the nominal author. "Content accuracy" is the primary guarantee of this attribution. The minor procedural violations did not break this essential link, whereas creating a factually false document would have.

Conclusion

The 1976 ruling on the city hall official remains a cornerstone of Japanese forgery law. It established the vital principle that for an assisting official, the line between a punishable abuse of authority and the crime of forgery is drawn at the fundamental conditions of their role. As long as the document created is one the official is generally empowered to create and its content is accurate, procedural shortcuts taken for personal gain do not transform an authorized act into a forged one. The decision provides a nuanced and enduring framework for assessing criminal liability within complex organizations, wisely distinguishing between internal rule-breaking and the far more serious crime of corrupting the public's trust in the authenticity of official documents.