When an Impostor Loots a Deposit via a Secured Loan: A Bank's Shield Under Japanese Law

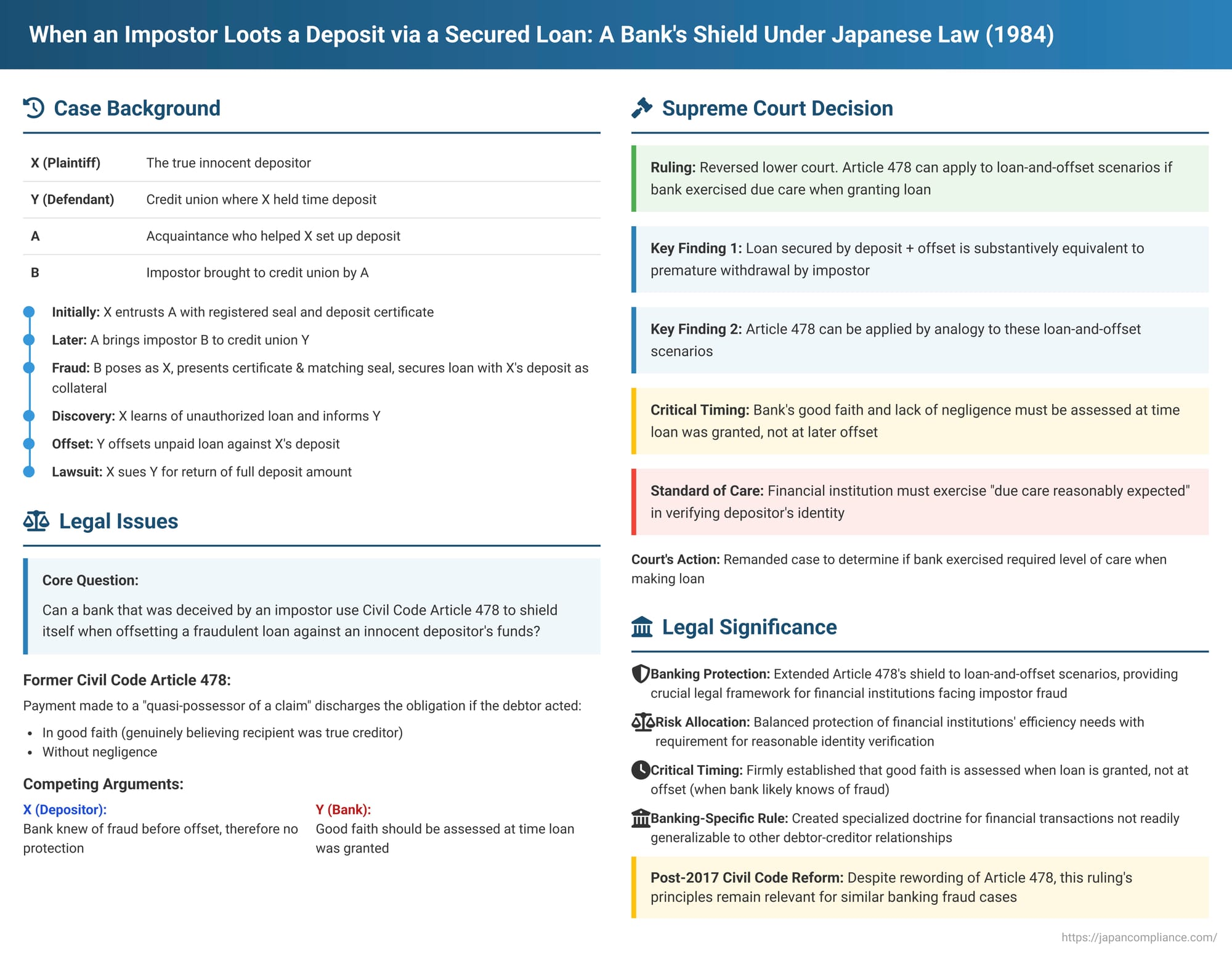

Imagine a scenario: a con artist, armed with your bank passbook and a replica of your registered seal, approaches your bank. Posing as you, they take out a loan, pledging your time deposit as security. Later, when the loan isn't repaid, the bank "offsets" the outstanding loan amount against your hard-earned deposit. Can the bank legally do this, leaving you, the true depositor, out of pocket? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this distressing situation in a landmark judgment on February 23, 1984 (Showa 55 (O) No. 260), offering a degree of protection to financial institutions, but only if they exercise due care. This case significantly explored the reach of (former) Civil Code Article 478, which dealt with payments made to an "apparent creditor."

The Legal Shield: (Former) Article 478 – Payment to a "Quasi-Possessor of a Claim"

Before diving into the case, it's essential to understand (former) Article 478 of the Japanese Civil Code. This provision offered a defense to debtors: if a debtor made a payment to someone who wasn't the true creditor but had the "outward appearance of being entitled to receive payment" (referred to as a saiken no jun-senyūsha, or "quasi-possessor of the claim"), the debtor was discharged from their obligation if they made the payment in good faith (genuinely believing the recipient was the true creditor) and without negligence. This rule aimed to protect the safety and certainty of transactions where appearances could be misleading. (While the wording of Article 478 was updated in the 2017 Civil Code reforms to "one who has the outward appearance of a person entitled to receive payment in light of common sense in transaction," the underlying principle of protecting a payer who acts in good faith and without negligence remains similar.)

Facts of the 1984 Case: The Impostor, the Loan, and the Offset

The 1984 case involved a classic impostor scenario:

- The Parties:

- X: The true and innocent depositor (plaintiff/appellee).

- Y: The credit union where X held a time deposit (defendant/appellant).

- A: An acquaintance who had initially helped X set up the time deposit with Y. X had briefly entrusted A with the registered seal and had left the deposit certificate with A for an extended period.

- B: An impostor, brought to the credit union by A.

- The Fraudulent Loan: A, accompanying B, visited Y credit union. B, convincingly posing as the depositor X, applied for a loan, offering X's registered time deposit as collateral. B presented X's actual deposit certificate and used a seal that matched X's registered seal impression on the loan application documents. Y credit union, after verifying the certificate and the seal impression, mistakenly believed B to be the genuine depositor X and granted the loan to B, taking a pledge (a form of security interest) over X's time deposit.

- Discovery and Offset: Later, X, the true depositor, learned about this unauthorized loan and informed Y credit union that X had never consented to it. Subsequently, Y credit union, presumably because the loan taken by the impostor B was not repaid, notified X that it was offsetting the outstanding loan amount against X's time deposit.

- The Lawsuit: X sued Y credit union for the return of the full deposit amount, arguing that the offset was invalid because X had never taken out or authorized the loan. The lower appellate court had ruled in favor of X, finding that Y credit union knew of the fraud (i.e., that B was not X) by the time it performed the offset, and therefore could not claim protection. Y credit union appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that its good faith and lack of negligence should be assessed at the earlier point in time when the loan was actually granted to the impostor.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Extending Article 478 by Analogy

The Supreme Court reversed the appellate court's decision and remanded the case for further consideration of the bank's diligence at the time of the loan. The Court laid down several crucial principles:

- Loan Secured by Deposit + Subsequent Offset is Substantively Like a Premature Withdrawal: The Court held that the entire sequence of events—a financial institution granting a loan to an impostor secured by a genuine deposit, followed by an offset of that loan against the deposit when the loan defaults—can, at least concerning the validity of the offset, be substantively equated to a premature withdrawal (early termination and payout) of the time deposit by an impostor. The Court found it "appropriate" to view it this way.

- Analogous Application of Article 478 is Possible: Building on the first point, and drawing from an earlier 1966 Supreme Court precedent which had held that actual premature withdrawals by impostors could be covered by Article 478 (as a type of "payment"), the Court ruled that Article 478 could be applied by analogy to these loan-and-offset scenarios.

- Bank Protected if Diligent at the Loan Disbursement Stage: If the financial institution, when it granted the loan and took the security interest in the deposit, had exercised the due care reasonably expected of a financial institution in such circumstances in verifying the identity of the person claiming to be the depositor, then the subsequent offset could be asserted as valid against the true depositor.

- Crucial Timing for Assessing Good Faith and No Negligence: This was a key clarification. The Supreme Court stated that the financial institution's good faith and lack of negligence must be assessed at the time the loan was actually granted and the security interest taken. The fact that the institution might have later learned of the fraud (e.g., through the true depositor's inquiry) before formally declaring the offset does not negate its protection under Article 478, provided it was diligent at the initial loan stage.

The case was sent back to the appellate court to specifically determine whether Y credit union had exercised the required level of care when it originally made the loan to the impostor B.

Why This Approach? Rationale and Implications

This 1984 judgment represented a significant step in clarifying how losses from such banking frauds are allocated.

- Facilitating Routine Banking Transactions: The Supreme Court's reasoning was partly based on the practicalities of banking. Loans secured by deposits are common and routine. Applying stricter legal doctrines like "apparent agency" (which often requires proving some fault or responsible connection on the part of the true principal/depositor for the impostor's actions) could unduly slow down these everyday transactions by imposing more complex verification burdens on banks. The Article 478 analogy was seen as more conducive to the efficient processing of such transactions.

- Focus on the Loan as the Critical Act of Reliance: By pinpointing the moment of loan disbursement as the critical time for assessing the bank's diligence, the Court recognized that this is when the bank commits its funds and relies on the apparent validity of the transaction and the security. The bank's expectation of being able to offset against the deposit if the loan defaults is formed at this stage.

- Evolution of Case Law: This decision built upon earlier precedents. A 1966 case had equated premature deposit withdrawals with "payment" under Article 478. A 1973 case had applied this by analogy to loan-and-offset scenarios involving unregistered time deposits (where depositor identity was inherently less clear). The 1984 judgment confirmed this analogous application even for registered time deposits (where the bank knew the depositor's name but was tricked by an impostor) and decisively set the timing for evaluating the bank's care.

- Scholarly Debate: While this line of Supreme Court reasoning became established, it was not without criticism from some legal scholars. Some argued that the analogy to "payment" in these loan-and-offset situations was too strained and that doctrines like apparent agency or rules concerning unauthorized dispositions might offer a more theoretically sound framework, especially to protect true depositors who were entirely without fault in the impostor's ability to deceive the bank. However, the courts have consistently followed the Article 478 analogy in these specific banking contexts.

A Specialized Rule for Banking Transactions

It's important to underscore, as legal commentators have, that this expansive analogous application of Article 478 is a highly specific doctrine developed by the Japanese courts primarily for the unique environment of standardized, high-volume financial institution deposit and lending transactions. It is not a principle that should be readily generalized to other types of debts or payments in non-banking contexts. The rationale is strongly tied to the operational needs and risk management particular to financial institutions.

Relevance After the 2017 Civil Code Reforms

Although Article 478 of the Civil Code was reworded in the 2017 reforms (now referring to payment to "one who has the outward appearance of a person entitled to receive payment in light of common sense in transaction" rather than the older term "quasi-possessor of a claim"), the fundamental principle of protecting a payer who acts in good faith and without negligence remains. Therefore, the reasoning and principles of this 1984 Supreme Court judgment—particularly concerning the analogous application to loan-secured-by-deposit and subsequent offset scenarios, and the critical timing for assessing the financial institution's diligence—continue to be highly relevant for interpreting the application of the current Article 478 in similar banking fraud cases.

Conclusion

The 1984 Supreme Court decision provided critical guidance for a common but perilous situation in banking: fraud involving loans secured by an innocent party's deposit. By allowing financial institutions to invoke an analogous application of Article 478 and by focusing the assessment of their due diligence on the time of the loan disbursement, the Court aimed to balance the protection of transactional efficiency in banking with the need for reasonable care by institutions. This judgment remains a key precedent, reminding financial institutions of their responsibility to diligently verify borrower identity while offering a shield if they are non-negligently deceived by a convincing impostor. For depositors, it underscores the importance of safeguarding deposit certificates and registered seals.