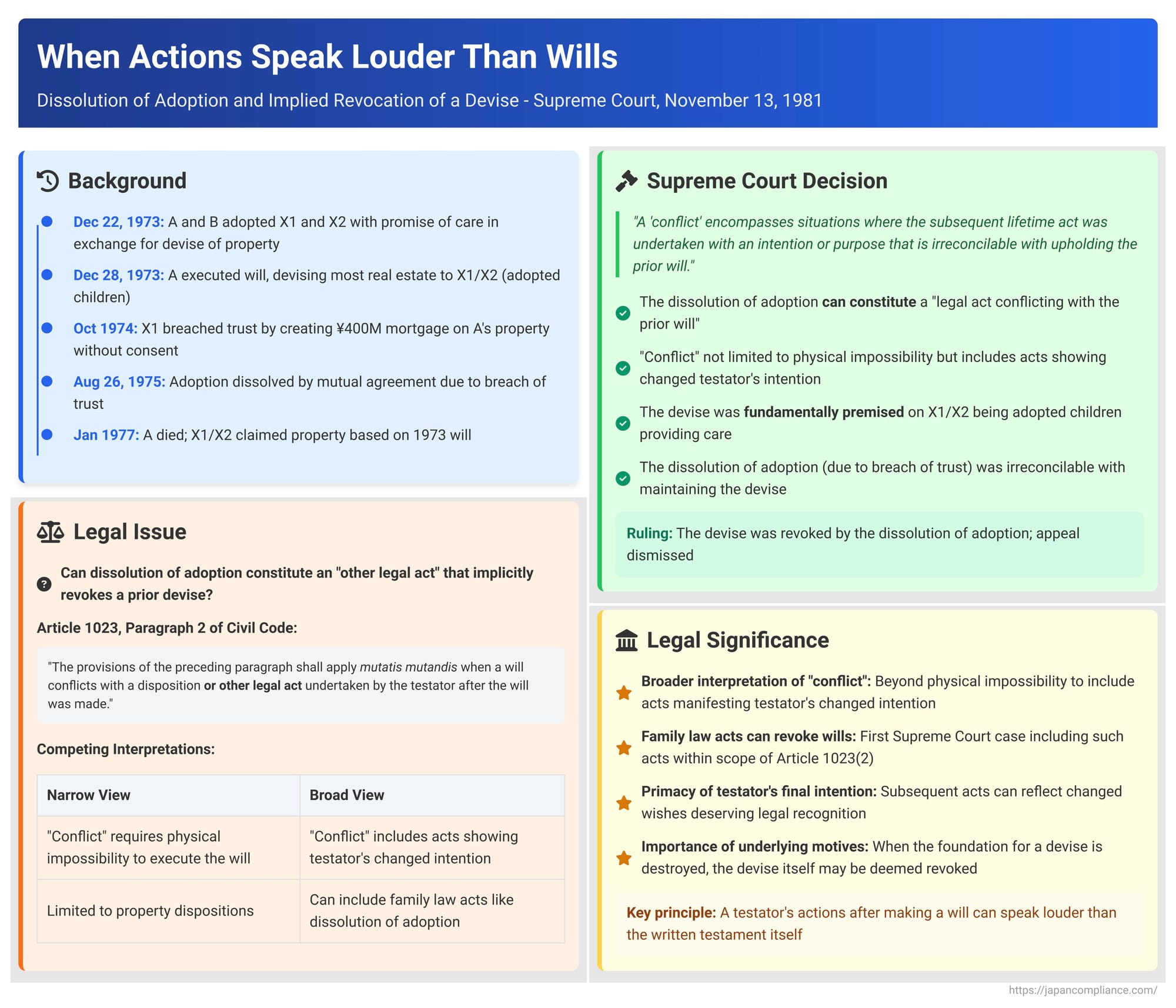

When Actions Speak Louder Than Wills: Dissolution of Adoption and Implied Revocation of a Devise

Date of Judgment: November 13, 1981 (Showa 56)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 56 (o) No. 310 (Claim for Ownership Transfer Registration)

A will is a formal declaration of a person's wishes for the disposition of their property after death. While a testator can explicitly revoke a will by making a new one or by physically destroying the old one, Japanese law also recognizes situations where a will can be deemed implicitly revoked. Article 1023, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code provides that if a will conflicts with a lifetime disposition or "other legal act" undertaken by the testator after the will was made, the will is considered revoked to the extent of the conflict. A key question arises: what constitutes such a conflicting "legal act," especially when it's not a direct disposition of the same property? Can a significant change in family status, like the dissolution of an adoptive relationship, be deemed to revoke a prior devise made to the adopted children? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this complex issue in its decision on November 13, 1981.

Facts of the Case: An Adoption for Care, A Devise, a Breach of Trust, and Dissolution

The case involved a testator, A, his wife B, their adopted children X1 and X2 (the plaintiffs/appellants), and A's non-marital child Y (one of the defendants/appellees).

- Family Background and Need for Care: A and his wife B had no biological children together. A had a non-marital child, Y, but Y did not live with A and B. The couple had previously attempted other adoptions for caregiving purposes, but these arrangements had not been successful. As B later suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and required care, A and B sought to adopt individuals who could provide them with lifelong support.

- The Adoption Agreement with X1 and X2: They approached X1 and X2, a married couple related to B's family. X1 and X2 were initially hesitant about adoption. However, A made them a proposal: if they agreed to become his and B's adopted children, live with them, and provide care for the remainder of their lives, A would devise the bulk of his real estate ("the Property") to X1 and X2. A indicated that his non-marital child, Y, would only receive the specific house and land where Y was currently residing. Based on this understanding, X1 and X2 consented to the adoption.

- Formal Adoption and Execution of the Will: The adoption of X1 and X2 by A and B was legally formalized on December 22, 1973 (Showa 48). X1 and X2 then moved in with A and B and commenced their duties of cohabitation and care. True to his word, on December 28, 1973, A executed a formal notarized will (the "Will"). This Will stipulated that:

- All of A's cash and bank deposits would be devised to his wife, B.

- A specific house and parcel of land would be devised to his non-marital child, Y.

- All of A's remaining real estate (the Property at the heart of the dispute) would be devised to X1 and X2 in equal one-half shares.

- The Breach of Trust by X1: In October 1974, a serious issue arose. It was discovered that X1 (one of the adopted sons), along with his biological brother, had, without A's knowledge or consent, used A's real estate (part of the Property devised to X1 and X2) to secure a very substantial business debt of ¥400 million for their company. They had done this by creating a revolving mortgage (根抵当権 - neteitōken) on A's property. When A learned of this unauthorized encumbrance, he was understandably enraged. X1 and his brother subsequently provided A with a written promise to have the mortgage and related registrations cancelled within six months and also to repay a separate ¥15 million loan their company had taken from A. However, they failed to fulfill these promises.

- Dissolution of the Adoptive Relationship: Having completely lost trust in X1 and X2 due to this breach and the failure to rectify it, A and B requested a dissolution of the adoptive relationship. X1 and X2 consented to this. The adoption was formally dissolved by mutual agreement (協議離縁 - kyōgi rien) on August 26, 1975 (Showa 50). Following the dissolution, X1 and X2 moved out of A and B's home.

- Subsequent Care Arrangements and Deaths: After X1 and X2 left, they no longer provided any care or support to A and B. Instead, A's non-marital child, Y, and Y's spouse took over the responsibility of looking after A and B. A passed away on January 8, 1977, and his wife B passed away shortly thereafter on February 1, 1977.

- X1 and X2's Claim Based on the Will: After the deaths of A and B, X1 and X2 (the former adopted children) filed a lawsuit against Y and A's other legal heirs. They asserted that they had acquired ownership of the Property by virtue of A's 1973 Will and sought a court order for the transfer registration of the Property into their names.

- Lower Court Rulings – Devise Deemed Revoked: Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled against X1 and X2. These courts held that the subsequent dissolution of the adoptive relationship by mutual agreement between A (the testator) and X1/X2 (the devisees) constituted a "legal act conflicting with the prior will" within the meaning of Article 1023, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code. Consequently, they concluded that the devise of the Property to X1 and X2 in A's Will was deemed to have been implicitly revoked by this later act of dissolving the adoption.

- Appeal by X1 and X2 to the Supreme Court: X1 and X2 appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Dissolution of Adoption Implied Revocation

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2, thereby affirming the lower courts' conclusion that the devise had been revoked.

The Supreme Court's reasoning centered on the interpretation of Article 1023, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code:

- Interpreting "Conflict" (抵触 - Teishoku) Under Article 1023(2):

- The Court began by explaining the framework of Article 1023. Paragraph 1 states that if a later will conflicts with an earlier will, the earlier will is deemed revoked to the extent of that conflict. Paragraph 2 extends this principle, applying it mutatis mutandis (with necessary changes) when a will conflicts with a subsequent lifetime disposition or "other legal act" undertaken by the testator.

- The Supreme Court emphasized that the legislative intent (法意 - hōi) behind Article 1023(2) is to give paramount importance to the testator's final manifested intention as expressed through their subsequent lifetime actions.

- Therefore, a "conflict" as envisaged by Article 1023(2) is not narrowly limited to situations where the subsequent lifetime act makes the physical execution of the prior will objectively impossible.

- Instead, a "conflict" also encompasses situations where, upon an objective observation of all surrounding circumstances, it is clear that the subsequent lifetime act was undertaken with an intention or purpose that is irreconcilable with upholding the prior will.

- Applying this Interpretation to the Dissolution of Adoption:

- The High Court had established as fact that A made the Will devising the Property to X1 and X2 on the fundamental premise that X1 and X2, as his adopted children, would provide him and his wife B with lifelong care and support. This expectation of care was the basis for the devise.

- However, due to X1's serious breach of trust (the unauthorized mortgaging of A's property) and the subsequent failure to make amends, A completely lost faith in X1 and X2. This breakdown of trust directly led to the mutual agreement to dissolve the adoptive relationship.

- As a direct result of this dissolution, A and B both legally (as adoptive parents) and factually (in terms of daily living) ceased to receive any care or support from X1 and X2. The very foundation of the earlier devise was thus destroyed by this subsequent legal act.

- The Supreme Court concluded that, under these circumstances, the agreed-upon dissolution of the adoptive relationship was unequivocally an act undertaken by A with an intention that was fundamentally inconsistent with and irreconcilable with maintaining the prior devise to X1 and X2. The devise was predicated on the adoptive relationship and the expectation of care, both of which were terminated by the dissolution.

- Therefore, the devise of the Property to X1 and X2 in A's Will was deemed to have been revoked by the subsequent act of dissolving the adoption, as this later act "conflicted" with the will in the broader, substantive sense intended by Article 1023(2) of the Civil Code.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1981 Supreme Court decision is a significant ruling that clarifies how a testator's subsequent lifetime actions, even those not directly disposing of property, can lead to the implied revocation of a prior will.

- Broad, Substantive Interpretation of "Conflict" (抵触 - teishoku) in Article 1023(2): The judgment affirms a broad interpretation of what constitutes a "conflict" sufficient to imply revocation. It is not limited to mere physical or objective impossibility of executing the will but extends to situations where a testator's later legal act clearly demonstrates a final intention that is incompatible with the earlier testamentary disposition. The PDF commentary notes that this approach is consistent with an earlier Daishin'in (Great Court of Cassation) precedent from Showa 18 (1943), which also adopted a similarly broad view of "conflict."

- "Other Legal Acts" Capable of Revoking a Will Can Include Family Law Acts: This decision is notable for explicitly recognizing that the "other legal acts" referred to in Article 1023(2) are not restricted to property dispositions (such as selling or gifting the devised asset to someone else). They can also include significant family law acts, such as the dissolution of an adoptive relationship by mutual agreement, if that act, viewed in context, clearly manifests an intention on the part of the testator that is contrary to the continued validity of a prior devise made in favor of the (now former) adopted child. The PDF commentary highlights this as the first Supreme Court case to clearly include such a family law act within the scope of Article 1023(2).

- Primacy of the Testator's Final Manifested Intention: The overarching principle guiding the Court's decision is the paramount importance of respecting and giving effect to the testator's final discernible intention. If a subsequent, deliberate legal act by the testator clearly indicates a change of heart or a repudiation of the fundamental basis upon which a prior devise was made, that later act can be seen as implying a revocation of the earlier testamentary wish.

- The Importance of the Underlying Motive or Premise of the Devise: In this case, the fact that the devise of the Property to X1 and X2 was inextricably linked to their adoption and A's expectation that they would provide lifelong care was crucial. When this foundational premise collapsed due to X1's breach of trust, leading directly to the mutual dissolution of the adoption, the rationale for the devise also ceased to exist from A's perspective. This connection allowed the Court to infer a revoking intent from the act of dissolution.

- Scholarly Critiques and Alternative Legal Constructions: The PDF commentary notes that this broad interpretation of "conflict" has faced some scholarly criticism. Some legal commentators argue that for Article 1023(2) to apply, the "conflict" should ideally be between acts of a similar nature (e.g., a property devise being implicitly revoked by a subsequent disposition of the same property). Treating a family law act like the dissolution of adoption as directly "conflicting" with a property devise is viewed by these critics as potentially overextending the concept of "conflict."

These critics suggest that similar outcomes (denying the devise to X1 and X2 under these facts) might have been achievable through other legal avenues without resorting to such a broad interpretation of implied revocation. For instance, the devise could have been interpreted from the outset as being implicitly or explicitly conditional upon the continuation of the adoptive relationship and the provision of care. Alternatively, X1 and X2's attempt to claim the devise after their serious breach of trust and the subsequent dissolution of the adoption could potentially have been viewed as an abuse of rights. The PDF commentary suggests that this specific case might have been resolved by focusing on the failure of the underlying motive or condition for the devise, rather than solely relying on the dissolution of adoption as the revoking "legal act." - Distinction from Formal Revocation of a Will: It is important to remember that Article 1023 deals with implied revocation by subsequent conflicting acts. The primary and most straightforward ways for a testator to revoke a will remain through the execution of a new will that explicitly or implicitly revokes the old one (Article 1022) or by the physical destruction of the will document with revocatory intent (Article 1024, first part).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1981 decision in this case provides a significant illustration of how a testator's subsequent lifetime legal acts, even those not directly involving the disposition of property, can be interpreted as implying a revocation of a prior will under Article 1023, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code. By focusing on the testator's final manifested intention and the irreconcilability of the subsequent act (the dissolution of adoption due to a breach of trust) with the premise of the original devise (lifelong care from adopted children), the Court adopted a substantive rather than purely formalistic approach to the concept of "conflict." This ruling underscores that relationships and expectations that form the very basis of a testamentary gift can, if fundamentally altered by the testator's later actions, lead to the deemed revocation of that gift.