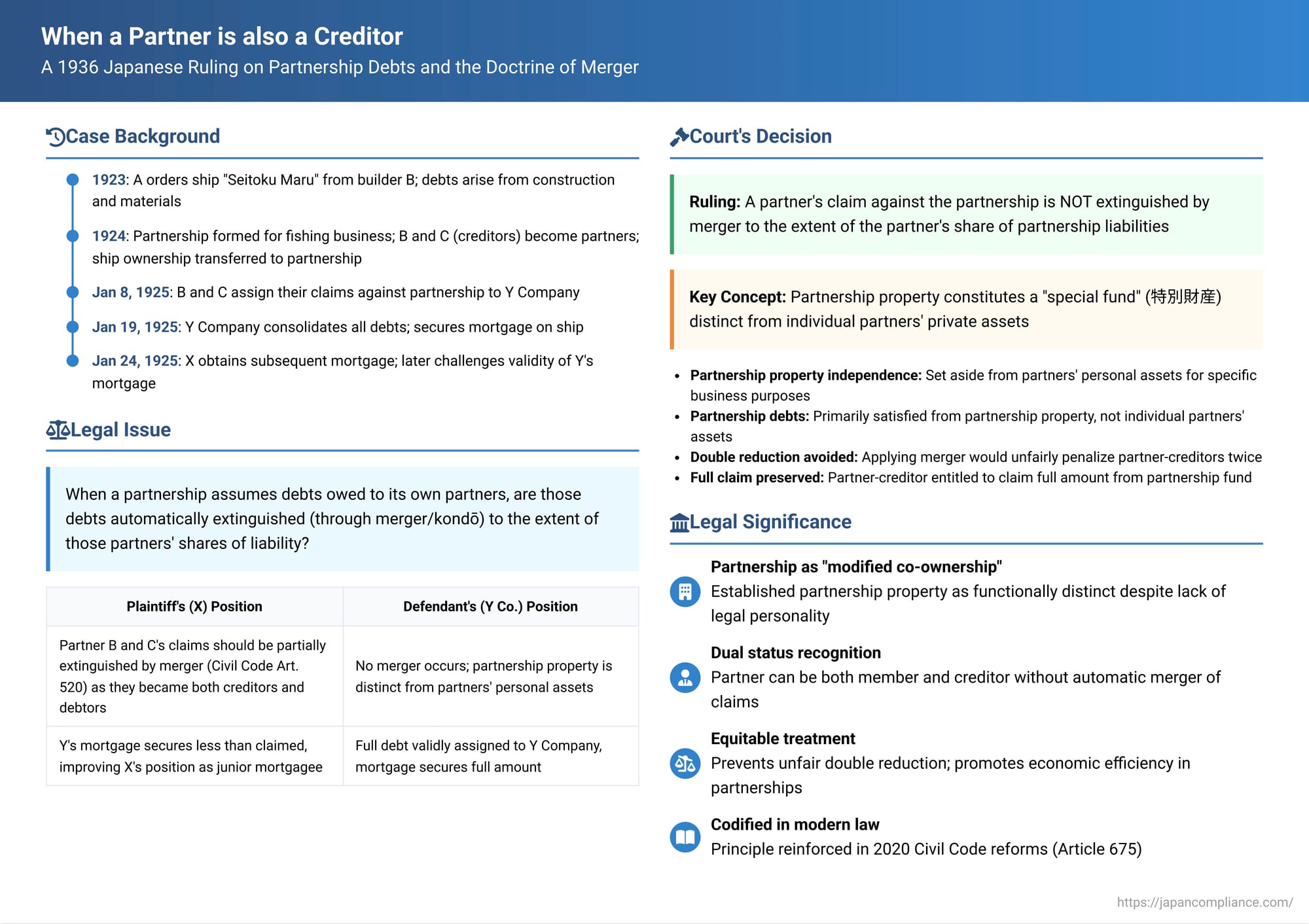

When a Partner is also a Creditor: A 1936 Japanese Ruling on Partnership Debts and the Doctrine of Merger

Date of Judgment: February 25, 1936

Case Name: Claim for Confirmation of Invalidity of Mortgage

Court: Daishin-in (Former Supreme Court of Japan), Fifth Civil Department

Introduction

Partnerships, known as "kumiai" (組合) under Japanese Civil Code, are a common structure for joint business ventures. Unlike corporations, traditional Japanese partnerships do not possess a separate legal personality distinct from their members. This characteristic raises interesting legal questions, particularly concerning the treatment of partnership assets and debts. A notable decision by the Daishin-in (the predecessor to the modern Supreme Court) on February 25, 1936, addressed a key issue: if a partnership owes a debt to one of its own members, is that debt automatically reduced or extinguished by the legal doctrine of "merger" (混同 - kondō), where a single person becomes both debtor and creditor?

A Ship, A Partnership, and Entangled Debts: The Factual Background

The case involved a complex series of transactions centered around a sailing ship named "Seitoku Maru":

- Initial Debts and Parties:

- A: Ordered the construction of the ship "Seitoku Maru" (let's call her "Ship K") from B in 1923.

- B (Shipbuilder): Upon completing Ship K, B held a claim against A for the construction price (Debt 1). B also had a separate loan claim against A (Debt 2).

- C (Material Supplier): Supplied materials for Ship K's construction and held a claim against A for the price (Debt 3).

- Y Company (Material Supplier): Also supplied materials and held a claim against A (Debt 4).

- Formation of the Partnership: Around the summer of 1924, a partnership (the "Subject Partnership") was formed for the purpose of conducting a fishing business using Ship K. B (the shipbuilder) and C (a material supplier) were original members of this partnership. Ownership of Ship K was transferred to the Subject Partnership. However, because a traditional Japanese partnership lacks separate legal personality, the ship's ownership was nominally registered in the names of three individuals: A (the original orderer), B (the builder/partner), and D (another individual, likely all three acting as directors or representatives of the partnership).

- Assumption of Debts and Assignments:

- The Subject Partnership formally assumed A's Debts 1, 2, 3, and 4. For registration and nominal purposes, the debtors for this assumed obligation were recorded as the same individuals: A, B, and D.

- On January 8, 1925, B assigned his claims (Debts 1 and 2, now effectively owed by the partnership) to Y Company. On the same day, C assigned his claim (Debt 3, also now owed by the partnership) to Y Company. Formal notifications of these assignments were completed by January 13.

- Consolidation of Debt and First Mortgage: On January 19, 1925, Y Company (now the creditor for Debts 1, 2, and 3, in addition to its own original Debt 4) entered into a new loan agreement by way of novation (a "quasi-loan for consumption" or 準消費貸借 - jun-shōhi taishaku) with A, B, and D (acting nominally for the partnership). This new agreement consolidated all four original debts plus Y Company's expenses for establishing a mortgage, into a single new debt totaling ¥7,133. To secure this consolidated debt, a mortgage (the "Subject Mortgage") was placed on Ship K and duly registered the same day.

- Subsequent Mortgage and Dispute: A few days later, on January 24, 1925, X (the plaintiff in this case) obtained a separate, subsequent mortgage on Ship K, which was also registered. X then filed a lawsuit against Y Company, seeking a court declaration that Y Company's prior Subject Mortgage was invalid, or at least partially invalid.

- X's Key Argument (Regarding Merger): A central argument made by X was that when the Subject Partnership assumed the debts owed to B and C (who were members of the partnership), those debts (Debts 1, 2, and 3) should have been partially extinguished by the legal doctrine of "merger" or "confusion of rights" (混同 - kondō, Civil Code Art. 520). This doctrine generally provides that a debt is extinguished if the debtor and creditor become the same person. X argued that because B and C were partners, they were also, in effect, co-debtors. Therefore, to the extent of B's and C's respective shares of liability for the partnership's debts, their claims against the partnership should have merged and disappeared. If so, the full original amounts of these debts could not have been validly assigned to Y Company, making the subsequent consolidated debt (and the Subject Mortgage securing it) smaller than claimed, thereby improving X's position as a junior mortgagee.

The lower courts rejected X's claim. X appealed to the Daishin-in.

The Daishin-in's (Old Supreme Court) Decision

The Daishin-in, on February 25, 1936, dismissed X's appeal, upholding the validity of Y Company's mortgage for the full consolidated amount. The Court rejected the argument that the debts owed to partners B and C were extinguished by merger when the partnership assumed them.

Core Reasoning of the Daishin-in:

- Partnership Property as a "Special Fund": The Court acknowledged that a partnership (kumiai) under the Civil Code does not have a separate legal personality like a corporation. However, it emphasized that partnership property (組合財産 - kumiai zaisan) constitutes a distinct aggregation of assets. This property is set aside from the individual partners' other private assets and is dedicated to the specific purpose of the partnership's business operations. It forms a "special property" (特別財産) or "purpose property" (目的財産).

- Independence of Partnership Property: As a consequence of this distinct nature, partnership property possesses a certain degree of independence. It is not to be confused or intermingled with the private property of the individual members. The Court cited various Civil Code provisions (such as those restricting a partner's ability to dispose of their share in specific partnership assets or demand partition before dissolution) as supporting this concept of separateness.

- Partnership Debts Payable from Partnership Property: Just as income and assets generated by the partnership belong to this common partnership fund, debts incurred in the course of the partnership's business ("partnership debts" or 組合債務) are primarily intended to be satisfied from the partnership property. Recourse to the individual partners' private assets for partnership debts is considered a secondary, not primary, avenue.

- A Partner Can Be a Creditor of the Partnership: This principle of distinctness applies even when one of the partnership's own members is also a creditor of the partnership. For example, if a partner lends money to the partnership, or acquires a claim from a third party against the partnership (as B and C effectively did when the partnership assumed A's debts to them), the partnership owes that debt to the partner-creditor.

- No Merger of Debt to the Extent of Partner's Share: Crucially, the Daishin-in ruled that when a partner holds such a claim against the partnership, the claim is not extinguished by the doctrine of merger (kondō) to the extent of that partner-creditor's own share of the partnership's general liabilities. The partner-creditor is entitled to seek repayment of the full amount of their specific claim from the distinct partnership property fund.

- Rationale Against Merger in This Context: The Court reasoned that if merger were applied to reduce the partner's claim, it would lead to an unfair and economically unsound result. The partner-creditor would effectively suffer a double reduction: first, their specific claim against the partnership fund would be diminished. Second, when the partnership's affairs are eventually wound up, their share in the remaining partnership assets (which would have been further depleted by paying even the reduced debt) would also reflect their portion of that debt. This would disproportionately penalize the partner who also happened to be a creditor. Allowing the partner to claim the full amount from the partnership fund, and then accounting for their share of profits or losses (including their share of bearing that debt as a partnership liability) in the overall partnership accounting, was deemed the more equitable and logical approach.

Therefore, the Daishin-in concluded that B's and C's claims against the Subject Partnership remained fully intact when the partnership assumed them. These full claims were validly assigned to Y Company, formed the basis of the consolidated debt, and properly secured Y Company's mortgage.

The Nature of Partnership Property: Separate but Co-owned

This 1936 ruling is a cornerstone in understanding how Japanese law treats partnership property.

- A Special Form of Co-ownership: While the Civil Code (Art. 668) states that partnership property is "co-owned" (共有 - kyōyū) by all the partners, this is not typical tenancy-in-common. It's a modified form of co-ownership subject to specific restrictions reflecting the partnership's collective purpose. For instance:

- An individual partner cannot freely sell their "share" in a specific piece of partnership property to an outsider in a way that disrupts the partnership (Art. 676(1)).

- An individual partner generally cannot demand the physical partition or division of specific partnership assets before the partnership itself is dissolved (Art. 676(3), formerly 676(2)).

- Historically, debtors of the partnership could not typically set off that debt against a private debt owed to them by an individual partner, highlighting the separation of partnership claims from individual partner claims.

- Distinction from "Gōyū" (Collective Ownership): While some older legal theories in Japan drew on the German concept of "Gesamthandseigentum" (often translated as 合有 - gōyū, or collective ownership by a group as an undivided whole) to describe partnership property, modern Japanese jurisprudence and scholarship tend to analyze it as a special type of co-ownership (kyōyū) that is heavily modified by the specific statutory rules applicable to partnerships. The focus is less on a distinct abstract category of "gōyū" and more on the concrete effects of these statutory modifications to the basic co-ownership model. This 1936 Daishin-in judgment was instrumental in establishing this idea of partnership property as a "special fund" with functional independence.

Partnership Debts and Partner Liability

The 1936 judgment's principle that partnership debts are primarily a charge against partnership property has been reinforced and clarified in subsequent Civil Code reforms (effective 2020).

- Current Civil Code Article 675, Paragraph 1 explicitly states that partnership debts are to be borne by the partnership property.

- Paragraph 2 of the same article clarifies that individual partners also bear personal liability for partnership debts (typically in proportion to their agreed loss-sharing ratio, or equally if not specified), but this personal liability is generally considered alongside the primary recourse to partnership assets.

The 1936 Daishin-in decision focused on the debt as a liability of the partnership property fund itself. Because the partner (as creditor) and the partnership fund (as debtor) were seen as sufficiently distinct for this purpose, the conditions for extinguishing the debt by merger were not met.

Conclusion

The 1936 Daishin-in ruling on the Seitoku Maru case established a vital principle in Japanese partnership law: the distinct character of partnership property as a "special fund" prevents the automatic extinguishment (by merger) of a debt owed by the partnership to one of its own members. A partner who is also a creditor of the partnership can assert their full claim against the partnership assets. This decision underscores the functional separation maintained in Japanese law between a partnership's collective financial affairs and the individual financial positions of its members, ensuring that internal creditor-debtor relationships within the partnership structure are treated equitably without unfairly diminishing a partner-creditor's claim.