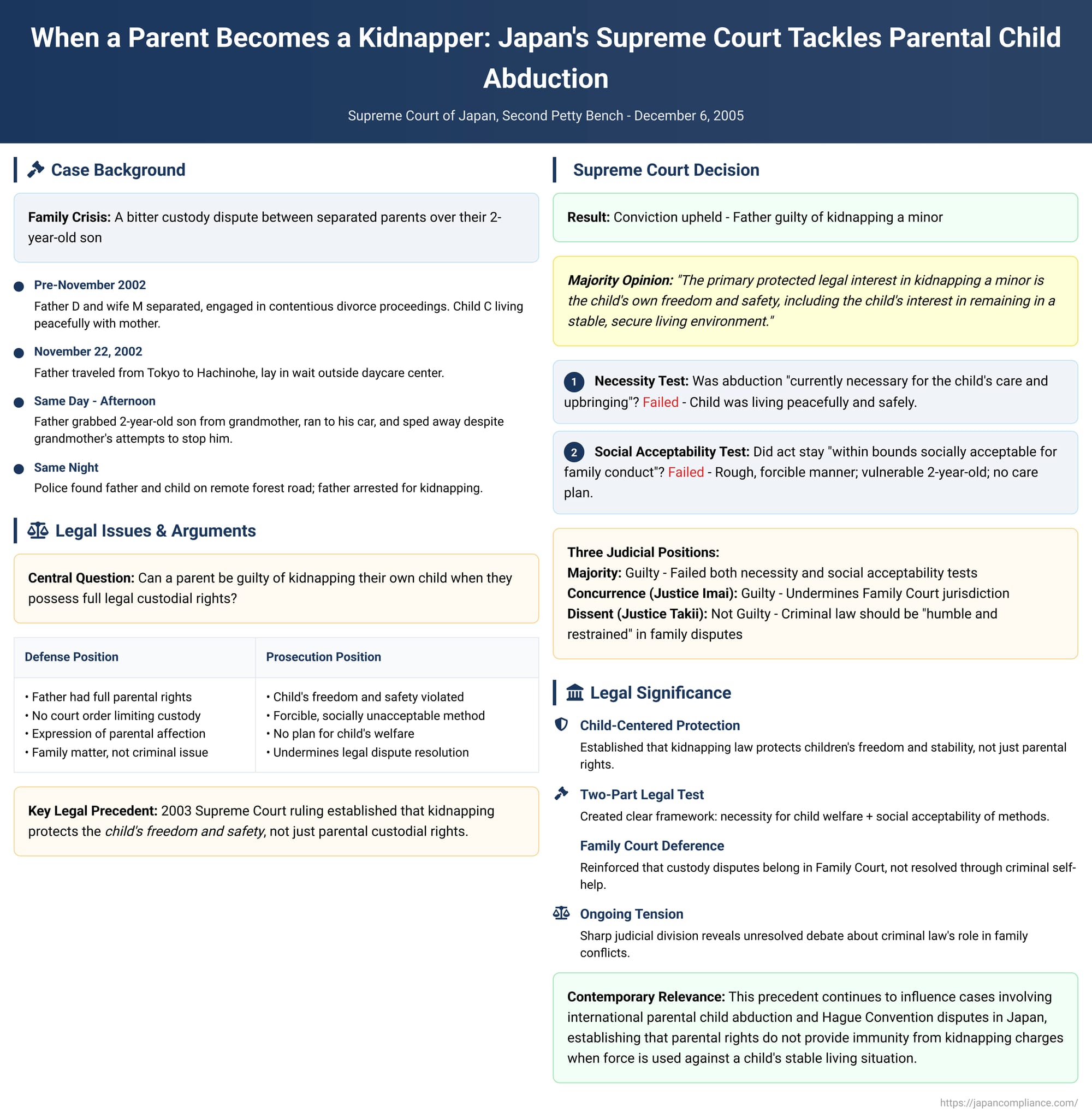

When a Parent Becomes a Kidnapper: Japan's Supreme Court Tackles Parental Child Abduction

Case Title: Case of Kidnapping of a Minor

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Decision Date: December 6, 2005

Introduction

The abduction of a child is one of the most emotionally charged issues in criminal law. But what happens when the perpetrator is not a stranger, but one of the child's own parents? In the midst of a bitter separation or divorce, when one parent forcibly takes a child from the other, is it a desperate act of love and an assertion of parental rights, or is it a criminal act of kidnapping?

This difficult question was the subject of a landmark 2005 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan. The case, involving a father who snatched his two-year-old son from the child's grandmother outside a daycare center, forced the Court to navigate the turbulent intersection of parental rights, a child's welfare, and the proper role of the criminal justice system in family disputes. The Court's sharply divided ruling, featuring a majority opinion, a strong concurrence, and an impassioned dissent, revealed the profound complexity of applying the crime of kidnapping to the parents themselves.

The Facts: A Desperate Act at Daycare

The case arose from a fraught family situation. The defendant, D, and his wife, M, were separated and embroiled in contentious divorce proceedings. Their two-year-old son, C, was living peacefully with his mother. Although the parents were separated, the defendant father still legally held full, unrestricted parental and custodial rights; no court order had been issued to limit them.

The father, wanting to take the child into his own care, traveled from Tokyo to Hachinohe, Aomori, where the child lived. On the afternoon of November 22, 2002, he lay in wait outside his son's daycare center. As the child's maternal grandmother, GM, was preparing to put the toddler into her car, the defendant sprang into action. He rushed forward, grabbed the two-year-old from behind, and ran at full speed to his own car, which he had left running with the doors unlocked. He jumped in with the child, locked the doors, and sped away, ignoring the grandmother's frantic attempts to stop him by banging on the car window.

Later that night, police discovered the father and child inside the car on a remote, unlit forest road and arrested the defendant. The investigation also revealed that this was not the first such incident; the father had previously been arrested for kidnapping after having a female acquaintance pose as a relative to lure the same child away from daycare.

The Threshold Question: Can a Parent Kidnap Their Own Child?

The first legal hurdle was to determine if a parent, who possesses custodial rights, can even be charged with kidnapping their own child under Article 224 of the Penal Code. If the crime's purpose were solely to protect the custodian's rights, a parent could not logically be found guilty of violating their own right.

The Supreme Court, affirming a prior 2003 ruling, held that the primary "protected legal interest" in the crime of kidnapping a minor is not the parent's custodial right, but rather the child's own freedom and safety. This includes the child's interest in remaining in a stable, secure living environment, free from being subjected to the de facto physical control of another by force. A parent's custodial right is merely a reflection of their duty to provide that safe environment, not an independent right to be vindicated through the criminal code. Because a parent is capable of violating their own child's freedom and stable environment, a parent can, in principle, be the perpetrator of the crime. The fact that the kidnapper is a parent is not a defense to the charge itself, but a factor to be considered when determining if the act was unlawful.

The Majority's Verdict: A Two-Part Test for Unlawfulness

Having established that the father's actions met the basic definition of kidnapping, the majority of the Court then turned to whether the act was nevertheless legally justified. They laid out a two-part test to determine if a parent's abduction of their child is unlawful.

- The Necessity Test: Was there a "special circumstance" making the abduction "currently necessary for the child's care and upbringing"? This would apply, for example, if a parent were rescuing a child from a situation of abuse or neglect. In this case, the Court found no such necessity. The child was living peacefully and safely under the mother's care.

- The Social Acceptability Test: Did the act stay "within the bounds socially acceptable for conduct among family members"? The Court found that the father's actions far exceeded these bounds, pointing to three key factors:

- The "rough and forcible" manner of the abduction.

- The child's vulnerability as a two-year-old toddler with no capacity to understand or choose his living situation.

- The father's lack of any "firm plan for the child's care and upbringing" after the abduction, evidenced by their discovery on a remote forest road late at night.

Finding that the act was neither necessary nor socially acceptable, the majority concluded that the father's conduct was unlawful and upheld his conviction for kidnapping a minor.

The Concurring Opinion: Deference to the Family Court

Justice Imai, in a concurring opinion, agreed with the guilty verdict but emphasized a different rationale. He argued that the paramount issue was the integrity of the legal system. Family disputes, especially those concerning child custody, are the exclusive domain of the Family Court, a specialized body equipped to handle such matters with the child's welfare as its top priority.

By resorting to forcible self-help, the father was ignoring and undermining the proper legal channels for dispute resolution. Justice Imai warned that deeming such actions lawful would "encourage a trend of using force" to settle custody battles, a practice that is fundamentally detrimental to the child's well-being. Therefore, the act was illegal precisely because it represented a rejection of the rule of law in favor of brute force.

The Dissenting Opinion: A Call for Criminal Justice Restraint

Justice Takii offered a powerful dissent, arguing that while the father's actions technically fit the definition of kidnapping, they should have been found lawful. He contended that the criminal justice system should be extremely "humble and restrained" when intervening in custody disputes between parents.

He argued that the father's act, however misguided, was an expression of "parental affection" and was not done with any intent to harm the child. He warned that allowing a criminal conviction in such a case effectively weaponizes the criminal law, permitting one parent to use police and prosecutors to gain leverage over the other. This bypasses the careful, welfare-focused analysis of the Family Court and could perversely incentivize parents to file criminal complaints as a tactic in custody fights. In his view, the father's actions, while "going a bit too far," were within the bounds of "social acceptability" for a parent desperate to be with their child and should not have triggered criminal intervention.

Conclusion: A Continuing Debate

The 2005 Supreme Court decision is a critical marker in Japanese law, confirming that parental child abduction can be a serious crime. It establishes that a parent's actions will be judged against stringent tests of necessity and social acceptability. The ruling sends a clear message that parental rights are not absolute and do not provide a license to use force to settle custody disputes.

At the same time, the sharp division among the justices highlights a deep and unresolved tension. The case pits the legal system's need to condemn violent self-help and protect the rule of law against the long-standing principle that criminal law should tread lightly in the private sphere of the family. The decision provides a crucial legal framework, but it also reveals an ongoing debate about the proper and most effective role for the criminal justice system in resolving society's most painful family conflicts.