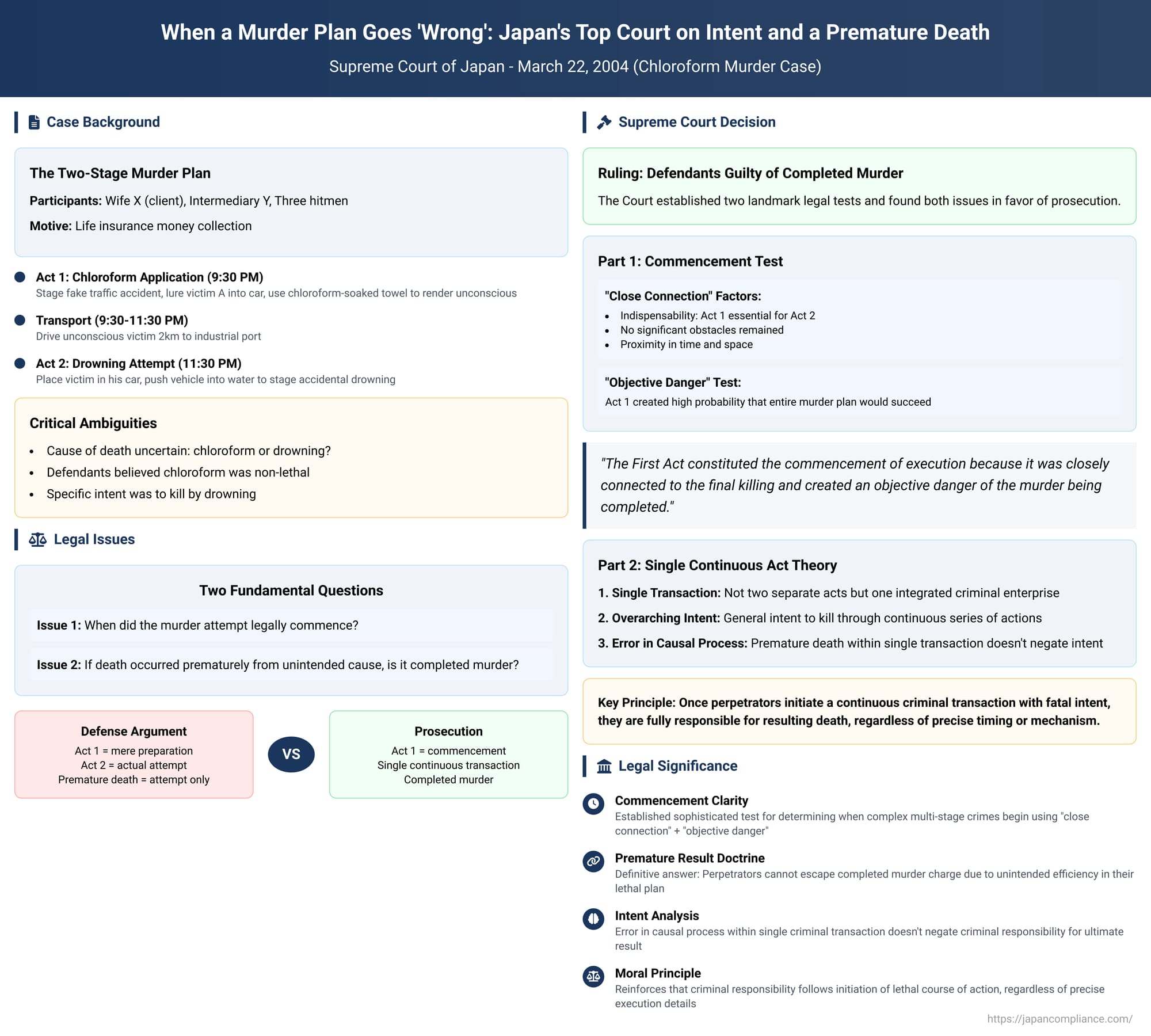

When a Murder Plan Goes 'Wrong': Japan's Top Court on Intent and a Premature Death

What happens when a meticulously planned murder succeeds, but not in the way the killers intended? If a victim dies from a preliminary step that the perpetrators thought was non-lethal, can they be guilty of completed murder, or only an attempt? And when, in a multi-stage plot, does the crime of murder actually begin? These profound questions of criminal law were at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 22, 2004. Known as the "Chloroform Murder Case," this ruling provides a masterclass in the legal principles of "commencement of execution" and criminal intent, offering definitive answers to the classic problem of a premature and unintended result.

The Two-Act Plan

The facts of the case read like a crime thriller. A woman, defendant X, wanted her husband, A, dead to collect life insurance money. She hired an intermediary, defendant Y, to arrange the killing. Y, in turn, recruited a team of three hitmen to carry out the act. The wife, X, left the specific method of execution to Y and his crew.

Y devised a two-stage plan designed to look like a tragic accident:

- The First Act: The hitmen would stage a minor traffic accident, intentionally rear-ending the husband A's car. Under the pretext of discussing insurance and repairs, they would lure A into their vehicle. Once he was inside, they would use a towel soaked in chloroform to render him unconscious.

- The Second Act: With A incapacitated, they would transport him to a remote location. There, they would place him back in his own car, push the vehicle into the water, and let him drown.

The hitmen set the plan in motion. They successfully staged the accident and lured A into their car. At around 9:30 PM, they executed the First Act, pressing a chloroform-soaked towel to A's face until he fell into a state of collapse. They then drove him approximately two kilometers to a nearby industrial port. After calling Y to the scene, the group, now including Y, put A's limp body into the driver's seat of his own car at around 11:30 PM. They then executed the Second Act, rolling the car off a pier and into the sea.

The subsequent investigation revealed two critical ambiguities:

- Uncertain Cause of Death: Medical examiners could not definitively determine if A died from drowning (the result of the Second Act) or from the direct effects of the chloroform (respiratory failure, cardiac arrest, or shock from the First Act). It was entirely possible he was already dead before his car hit the water.

- The Killers' Intent: Critically, the intermediary Y and the three hitmen did not believe the chloroform itself could be fatal. Their specific intent was to kill A by drowning in the Second Act; the chloroform of the First Act was merely a tool to make him unconscious and compliant.

This set up a complex legal battle. If the victim died sooner than planned, from a cause the killers did not intend, what crime had they committed?

Part 1: The Commencement of Murder - When Did the Attempt Begin?

Before addressing the question of the premature death, the Court first had to establish when the crime of murder legally began. The defense argued that the First Act (administering chloroform) was merely preparation, and that the actual murder attempt did not commence until the Second Act (pushing the car into the water).

The Supreme Court disagreed. It ruled that the commencement of execution began with the First Act. In doing so, it laid out a clear, multi-factor test for determining the start of a crime in a multi-stage plot, a test that has become highly influential in subsequent Japanese law. The Court found that the First Act constituted the beginning of the murder because it was both "closely connected" to the final killing and created an "objective danger" of the murder being completed.

The "Close Connection" Test

The Court assessed the "close connection" between the First and Second Acts based on three factors:

- Indispensability: The First Act was "indispensable" for making the Second Act "certain and easy." Knocking the victim unconscious was essential to their plan of staging an accident without a struggle.

- Lack of Obstacles: Once the First Act succeeded and A was unconscious, there were no significant remaining obstacles to completing the plan. The victim was incapacitated and under their total control.

- Proximity: The two acts were closely related in time and space. The port was only a few kilometers away, a short drive, and the entire sequence of events was planned to occur over a few hours.

The "Objective Danger" Test

Having established a close connection, the court found that the First Act created a clear "objective danger" that the murder would succeed. Importantly, legal analysis clarifies that this "danger" was not just the unforeseen medical risk of the chloroform itself. Rather, it was the danger that the entire murder plan, culminating in the drowning, would be successfully carried out. By incapacitating the victim, the perpetrators had crossed a critical threshold and created a high probability that their ultimate goal would be achieved.

Part 2: The Premature Result - A Fatal Error in the Plan?

Having established that the murder attempt began with the First Act, the Court turned to the second, more complex issue. If A died from the chloroform (the First Act), could the defendants be guilty of completed murder when they only had the specific intent to kill him by drowning (the Second Act)?

The defense argued that this mismatch should break the chain of culpability for completed murder. Since the killers lacked the specific intent to kill with the chloroform, they could at most be guilty of attempted murder (for the overall plan) and perhaps negligent homicide (for the unexpected result of the chloroform).

The Supreme Court decisively rejected this argument. It ruled that even if the victim died prematurely from the First Act, the defendants were guilty of completed murder.

The Court's reasoning was based on viewing the defendants' actions as a "single, continuous act of murder."

- A Single Transaction: The Court did not see two separate acts (an assault and a killing) but one integrated criminal transaction that began with the administration of chloroform and was intended to end with the victim's death.

- Overarching Intent: The defendants' intent was not just "to drown" the victim, but more broadly, "to kill" the victim through this continuous series of actions.

- Error in Causal Process: The fact that death occurred at an earlier point within this single transaction than they specifically anticipated was deemed a non-essential "error in the causal process" (因果関係の錯誤 - inga kankei no sakugo). In Japanese criminal law, such an error does not negate criminal intent as long as the general intent (to cause death) and the actual result (death) align within the scope of the single criminal act initiated by the perpetrator.

Essentially, once the defendants embarked on their murderous course of action by commencing the First Act, they became responsible for the death that resulted from it, regardless of whether the precise mechanism of death matched their expectations.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Clarity

The 2004 "Chloroform Murder" decision is a landmark ruling that brought remarkable clarity to two of the most challenging areas of criminal law.

First, it established a sophisticated and practical test for determining the commencement of a crime in complex plots, blending the concepts of "close connection" and "objective danger" to pinpoint the moment a plan transitions into a punishable attempt.

Second, it provided a definitive answer to the classic legal problem of a "premature result." The ruling confirms that once perpetrators initiate a continuous criminal transaction with fatal intent, they are fully responsible for the resulting death, even if it occurs in a manner or at a time they did not precisely foresee. It underscores a powerful legal and moral principle: you cannot escape responsibility for a completed crime just because your plan turned out to be more lethally efficient than you realized.