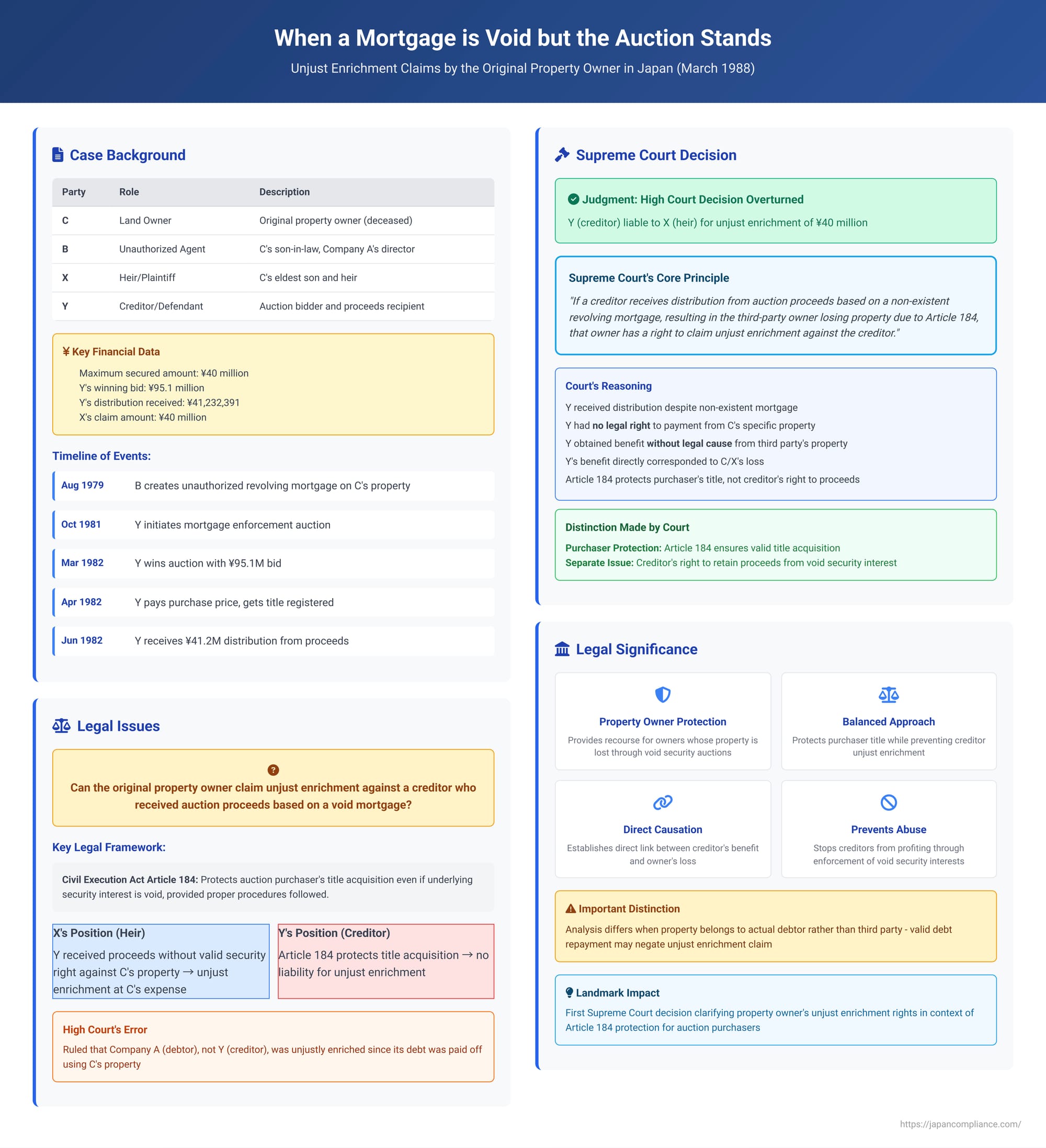

When a Mortgage is Void but the Auction Stands: Unjust Enrichment Claims by the Original Property Owner in Japan

In Japanese real property law, a mortgage provides a powerful tool for creditors to secure obligations. If a debtor defaults, the mortgagee can initiate a compulsory auction of the mortgaged property to recover the debt. A significant feature of Japan's Civil Execution Act (Article 184) is that it generally protects the title acquired by a bona fide purchaser at such an auction, even if the underlying mortgage is later found to be non-existent or extinguished, provided the original property owner did not successfully intervene to stop the auction through prescribed legal procedures.

This raises a critical question: If the original owner loses their property through an auction based on a void mortgage, but the auction purchaser still obtains valid title due to Article 184, does the original owner have any recourse to recover their loss? Specifically, can they sue the creditor who received the proceeds from the auction (in purported satisfaction of the invalidly secured debt) on the grounds of unjust enrichment? A 1988 Supreme Court of Japan decision provided a definitive answer to this complex interplay of property rights, execution law, and unjust enrichment principles.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved Mr. C, the owner of a parcel of land (the "Property"). Mr. B, the representative director of Company A and also Mr. C's son-in-law, purported to act as an agent for Mr. C. However, without Mr. C's actual authority, Mr. B created a revolving mortgage (ne-teitōken) on Mr. C's Property in August 1979. This mortgage, registered in November 1979, had a maximum secured amount of 40 million yen and was intended to secure Company A's existing and future loan obligations to Mr. Y (the defendant creditor).

Company A subsequently defaulted on its debts to Mr. Y. In October 1981, Mr. Y initiated a mortgage enforcement auction against Mr. C's Property based on this (unauthorized and thus void) revolving mortgage. In March 1982, Mr. Y himself participated in the auction and successfully bid 95.1 million yen for the Property. A sale permission decision was granted, and in April 1982, Mr. Y paid the purchase price to the court. The ownership of the Property was then registered in Mr. Y's name. In June 1982, from the auction proceeds, Mr. Y received a distribution of 41,232,391 yen as repayment towards the debt owed by Company A, purportedly secured by the (non-existent) mortgage on Mr. C's Property.

During the course of these auction proceedings, in February 1982, Mr. C passed away. Mr. C had previously made a will bequeathing all his property, including the Property in question, to his eldest son, Mr. X (the plaintiff).

Mr. X, as Mr. C's heir, then filed a lawsuit against Mr. Y. Mr. X argued that because the revolving mortgage on Mr. C's Property was fundamentally void due to its creation by an unauthorized agent, Mr. Y had no legal right to receive the distribution from the sale of that Property. Therefore, Mr. X claimed, Mr. Y had been unjustly enriched by the amount of 40 million yen (the portion of the distribution X sought to recover) at the expense of Mr. C (and now Mr. X).

The Matsue District Court (court of first instance) ruled in favor of Mr. X, ordering Mr. Y to return the amount deemed to be unjust enrichment.

However, the Hiroshima High Court (Matsue Branch), on appeal by Mr. Y, reversed the first instance decision and dismissed Mr. X's claim. The High Court's reasoning was that even if the auction purchaser (Mr. Y in this instance, as he bought the property himself) acquires valid title under Civil Execution Act Article 184 despite the non-existence of the mortgage, a different analysis applied to who was unjustly enriched by the proceeds. The High Court opined that when a debtor (Company A) uses a third party's property (Mr. C's land) without authority to secure its own debt, and the creditor (Mr. Y) subsequently receives auction proceeds from that property, which then extinguishes the debtor's (Company A's) debt to the creditor, the party unjustly enriched at the third-party owner's (Mr. C's) expense is primarily the debtor (Company A, whose debt was effectively paid off using Mr. C's asset), not the creditor (Mr. Y, who merely received payment for a debt owed by Company A).

Mr. X appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court of Japan. He argued, among other points, that while Civil Execution Act Article 184 might protect the auction purchaser's title as a matter of formal legal outcome, the substantive reality was that the creditor (Mr. Y) had received proceeds from a third party's (Mr. C's/X's) property without any valid underlying security right against that specific property. This, X contended, should constitute direct unjust enrichment of the creditor at the property owner's expense.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the High Court's decision. In a significant ruling, the Supreme Court agreed with the first instance court and found Mr. Y (the creditor) liable to Mr. X (the original owner's heir) for unjust enrichment. The Supreme Court then rendered its own judgment, rejecting Mr. Y's appeal from the first instance and upholding Mr. X's claim.

The Supreme Court laid down the following core principle:

If a creditor receives a distribution of sale proceeds from a mortgage enforcement auction based on a revolving mortgage that was, in fact, non-existent (e.g., because it was created by an unauthorized agent on a third party's property), and as a result of the auction purchaser paying the purchase price, that third-party owner loses ownership of the property (due to the legal effect of Civil Execution Act Article 184), then that third-party owner has a right to claim unjust enrichment under Article 703 of the Civil Code against the creditor who received the distribution.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was direct:

- The creditor (Mr. Y) received the distribution from the auction proceeds even though the revolving mortgage that formed the basis of the auction was non-existent.

- This means that Mr. Y had no substantive legal right to receive payment from the sale proceeds of Mr. C's specific property through the enforcement of that particular (non-existent) mortgage.

- By receiving this distribution, Mr. Y obtained a benefit (the partial satisfaction of his claim against Company A) derived from property belonging to a third party (Mr. C, and subsequently Mr. X). This benefit was obtained by Mr. Y without legal cause in relation to Mr. C's property.

- This benefit to Mr. Y directly corresponded to a loss suffered by the third party (Mr. C/X), who irretrievably lost their property due to the operation of Article 184 of the Civil Execution Act (which protected Y as the purchaser, but not necessarily Y as the recipient of funds from an invalid lien).

- Therefore, the creditor (Mr. Y) was unjustly enriched at the expense of the third-party property owner (Mr. C/X).

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1988 Supreme Court decision was a landmark judgment, providing crucial clarification on the rights of a property owner when their property is sold in an auction based on a non-existent mortgage, especially in light of Article 184 of the Civil Execution Act.

- The Role of Civil Execution Act Article 184: This article is central to understanding the context. Enacted in 1979, Article 184 was a significant legislative change. It provides that the acquisition of real property by a purchaser in an auction for the enforcement of a security interest is "not prevented by the non-existence or extinguishment of the security interest." The primary aim of this provision is to protect bona fide auction purchasers and enhance the stability and reliability of judicial auction sales. If an owner whose property is being auctioned based on an allegedly void or extinguished security interest fails to take timely and effective legal steps to halt the auction (e.g., by filing an execution objection under Article 182 of the Civil Execution Act or obtaining a provisional disposition to stop the sale under Article 183), Article 184 generally ensures that the purchaser who pays the price still acquires good title. The PDF commentary notes that this is often conceptualized as a form of "procedural preclusion" (shikkōkō) against the owner who failed to act.

- Who Bears the Loss? The Creditor, Not Just the Debtor: The High Court in this case had suggested that the primary party unjustly enriched was the original debtor (Company A), whose debt to Y was paid off using C's property. This would have left X with a potentially difficult claim against Company A (which might have been insolvent). The Supreme Court, however, decisively rejected this line of reasoning. It focused on the direct flow of benefit: C's property was lost, and Y, the creditor, received the monetary equivalent from that specific property without having a valid security claim against that property. This direct link established Y's unjust enrichment at X's expense. The PDF commentary indicates that this Supreme Court view is now widely supported in academic circles. The reasoning is that because Y's mortgage on C's property was non-existent, the payment Y received from the auction of C's property did not actually constitute a legally valid discharge of Company A's debt insofar as it relied on that specific, invalid security. Thus, Y received funds from a source (C's property) to which Y had no rightful claim via the purported mortgage.

- Limits of Article 184 – Protecting Purchasers, Not Necessarily Shielding Creditors from Unjust Enrichment: Article 184 protects the purchaser's acquisition of title. It does not automatically validate the creditor's right to the proceeds if their security interest was, in fact, void. The Supreme Court's decision makes it clear that these are two distinct issues. The auction purchaser (who was Y, the creditor, in this particular case, but could have been an unrelated third party) gets good title. However, the creditor who initiated the auction based on a non-existent security interest and received the proceeds may still be liable for unjust enrichment to the original owner who lost the property.

- Academic Debate on Exceptions to Article 184: The PDF commentary touches upon an ongoing academic debate about whether there should be exceptions to the purchaser-protective effect of Article 184, especially if the auction purchaser is the executing creditor themselves (as was the situation here) or if the purchaser was aware of the defect in the security interest at the time of purchase. Some scholars argue that the rationale for protecting bona fide purchasers under Article 184 (reliance on the appearance of a valid public sale) may not apply as strongly in such cases. However, in this 1988 decision, the Supreme Court proceeded on the premise that the purchaser (Y) did acquire valid title (as the High Court had also found, and X did not seem to dispute this aspect in the unjust enrichment claim itself), and then focused on the consequences for the distribution of proceeds. The specific question of whether Y, as a self-purchasing creditor with a non-existent mortgage, should have been protected by Article 184 regarding title acquisition was not the central issue decided by the Supreme Court in this unjust enrichment context, though the PDF commentary notes it as an interesting point of discussion.

- Alternative Recourse for the Property Owner: The PDF commentary also notes that, in theory, a property owner in X's position might have other options. For example, if X chose to consider the payment received by Y from the auction of C's property as a valid discharge of Company A's debt to Y, X might then have a claim for reimbursement against Company A (the debtor). This could be based on principles analogous to subrogation, negotiorum gestio (management of affairs without mandate), or compensation for a third party satisfying another's debt. However, the Supreme Court's decision affirms that this does not preclude a direct claim for unjust enrichment against the creditor (Y) who directly benefited from the proceeds of the wrongly encumbered property.

- Distinction from Sales of the Debtor's Own Property: It's important to note that the analysis might differ if the property auctioned had belonged to the actual debtor (Company A) rather than a third-party like C. In such a case, even if a mortgage on the debtor's own property was invalid, the distribution of proceeds from the debtor's property to satisfy a debt genuinely owed by the debtor might be seen as a valid (albeit unsecured) debt repayment, potentially negating an unjust enrichment claim by the debtor against the creditor. This case, however, specifically deals with the scenario where a third party's property is lost due to a non-existent mortgage securing another's debt.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1988 decision provides crucial protection for property owners whose assets are lost through compulsory auctions based on non-existent security interests, particularly in light of Article 184 of the Civil Execution Act which protects the title of auction purchasers. The Court clarified that even if the purchaser acquires valid title, the original property owner can bring an unjust enrichment claim directly against the creditor who received the distribution of the sale proceeds. This is because the creditor, lacking a valid security interest against that specific property, has no legal basis to retain the benefit derived from it at the owner's expense. This ruling underscores that while the execution system aims to provide finality for purchasers, it does not allow creditors to unjustly profit from the enforcement of void security interests against innocent third-party property owners.