When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

Imagine the police are questioning you about a friend who has been arrested for a serious crime. Out of loyalty or fear, you tell them a lie—a fabricated alibi designed to cast doubt on your friend's involvement. In many legal systems, lying to the police during an investigation, while discouraged, is not always a crime in itself unless it is under oath. But what if the lie is not spontaneous? What if you and your friend carefully coordinated your false stories beforehand in a deliberate attempt to mislead the authorities?

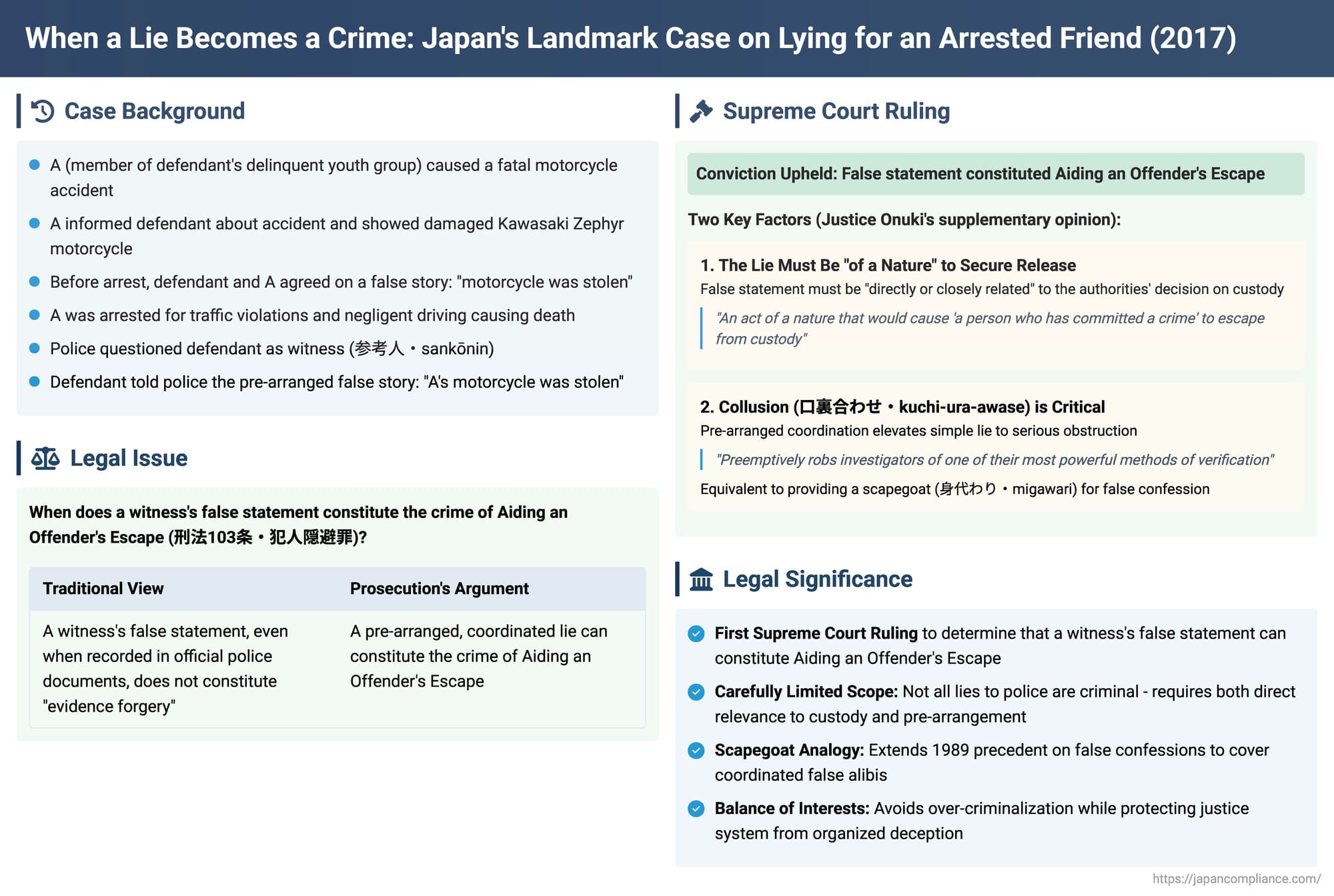

This critical question—of when a witness's false statement crosses the line into a criminal obstruction of justice—was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 27, 2017. The ruling, the first of its kind from the nation's highest court, established that while a simple falsehood may not be a crime, a pre-arranged, coordinated lie told to secure a suspect's release can constitute the serious offense of Aiding an Offender's Escape.

The Facts: The Fatal Accident and the Coordinated Alibi

The case began with a fatal motorcycle accident.

- The Incident: A man, A, who was a member of a delinquent youth group led by the defendant, was driving a motorcycle (a Kawasaki Zephyr) when he caused an accident that resulted in the death of another motorcyclist, B.

- The Conspiracy: After the accident, A informed the defendant about what had happened. The defendant, seeing the damage to A's motorcycle, anticipated that the police would identify A as the culprit. Before A was arrested, the defendant and A met and agreed on a false story: they would claim that A's motorcycle had been stolen just before the accident.

- The Arrest and Interrogation: A was later arrested by the police for violations including a breach of the Road Traffic Act and negligent driving causing death, and he was held in custody. The police then questioned the defendant as a witness (sankōnin).

- The False Statement: The defendant, aware that the police had identified A's motorcycle as the vehicle involved in the fatal crash, stuck to the pre-arranged story. He told the police, "I have never seen A actually riding a Zephyr. A said his Zephyr was stolen. I don't know anything about the motorcycle accident or who caused it." This was a completely false statement designed to make it seem as though the true culprit was not A, but an unknown thief.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of Aiding an Offender's Escape (Penal Code Art. 103). He appealed, arguing that his false statement did not constitute the crime.

The Legal Question: A Lie vs. Aiding Escape

The case presented a significant legal challenge. Japanese case law has historically held that a witness's false statement, even if it is recorded in an official police document, does not constitute the crime of "evidence forgery." How, then, could an act that is not considered evidence forgery be punished under the similar crime of Aiding an Offender's Escape? The Supreme Court needed to draw a very fine line.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Lie Plus Collusion Equals a Crime

The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, but in a carefully limited decision that avoided creating a general rule that all lying to the police is a crime. The Court found that the defendant's act was more than a simple lie; it was a calculated plot to free a criminal.

The Court's reasoning, clarified by a crucial supplementary opinion from Justice Onuki, was based on two key factors:

- The Lie Must Be "of a Nature" to Secure Release: The Court held that the defendant's false statement was an act "of a nature that would cause 'a person who has committed a crime' to escape from the custody in which they are currently held." The lie was not about a minor detail; it was a direct attack on the core of the police case. By claiming the motorcycle was stolen, the defendant's statement was specifically designed to "raise doubts about the continued custody of A as the offender." The supplementary opinion clarified that to be criminal, a false statement must be "directly or closely related" to the authorities' decision on whether to maintain custody.

- Collusion is a "Critical Factor": The fact that the defendant and the suspect had engaged in kuchi-ura-awase (a pre-arranged coordination of stories) was essential to the Court's finding. The supplementary opinion explained that this collusion elevates a simple lie to a much more dangerous form of obstruction. A lone witness's statement can be checked for credibility against other evidence. But when the witness and the suspect have coordinated their stories, it "preemptively robs the investigators of one of their most powerful methods of verification." This act of collusion "amplifies the truth-likeness" of the false statement and creates a danger of misleading the investigation that the Court found to be equivalent in severity to the act of providing a scapegoat to make a false confession.

Analysis: Drawing a Fine Line on False Statements

This 2017 ruling is significant as the first Supreme Court case to find that a witness's false statement can constitute the crime of Aiding an Offender's Escape.

- The Scapegoat Analogy: The Court's logic relies heavily on a 1989 precedent involving a "scapegoat" (migawari) who falsely confessed to a crime to free an arrested accomplice. The Court found that a coordinated false alibi, like the one in this case, is functionally equivalent to a scapegoat's false confession. Both are premeditated plots to deceive investigators about the identity of the true culprit and secure their release from custody.

- Avoiding Over-criminalization: The decision is carefully tailored to avoid the danger of criminalizing all lies told to police. It is the combination of (1) a lie that directly attacks the foundation of the suspect's detention and (2) the presence of a pre-arranged conspiracy with the suspect that elevates the act to a criminal offense. A spontaneous, uncoordinated lie about a peripheral detail would likely not meet this high standard.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2017 decision carves out a narrow but important exception to the general principle that a witness's false statement is not a crime in itself. It establishes that when a witness, acting in concert with an arrested suspect, tells a lie to police that is specifically designed to dismantle the grounds for the suspect's detention, that act can be prosecuted as Aiding an Offender's Escape. The ruling provides a clear warning that while simple falsehoods told to investigators may not be criminal, an organized and concerted effort to deceive the justice system through coordinated false alibis is a serious obstruction of justice that the law will punish.