When a Judgment Affects Those Unheard: Heirs and the Challenge of Posthumous Paternity Acknowledgments in Japan

Judgment Date: November 10, 1989 (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

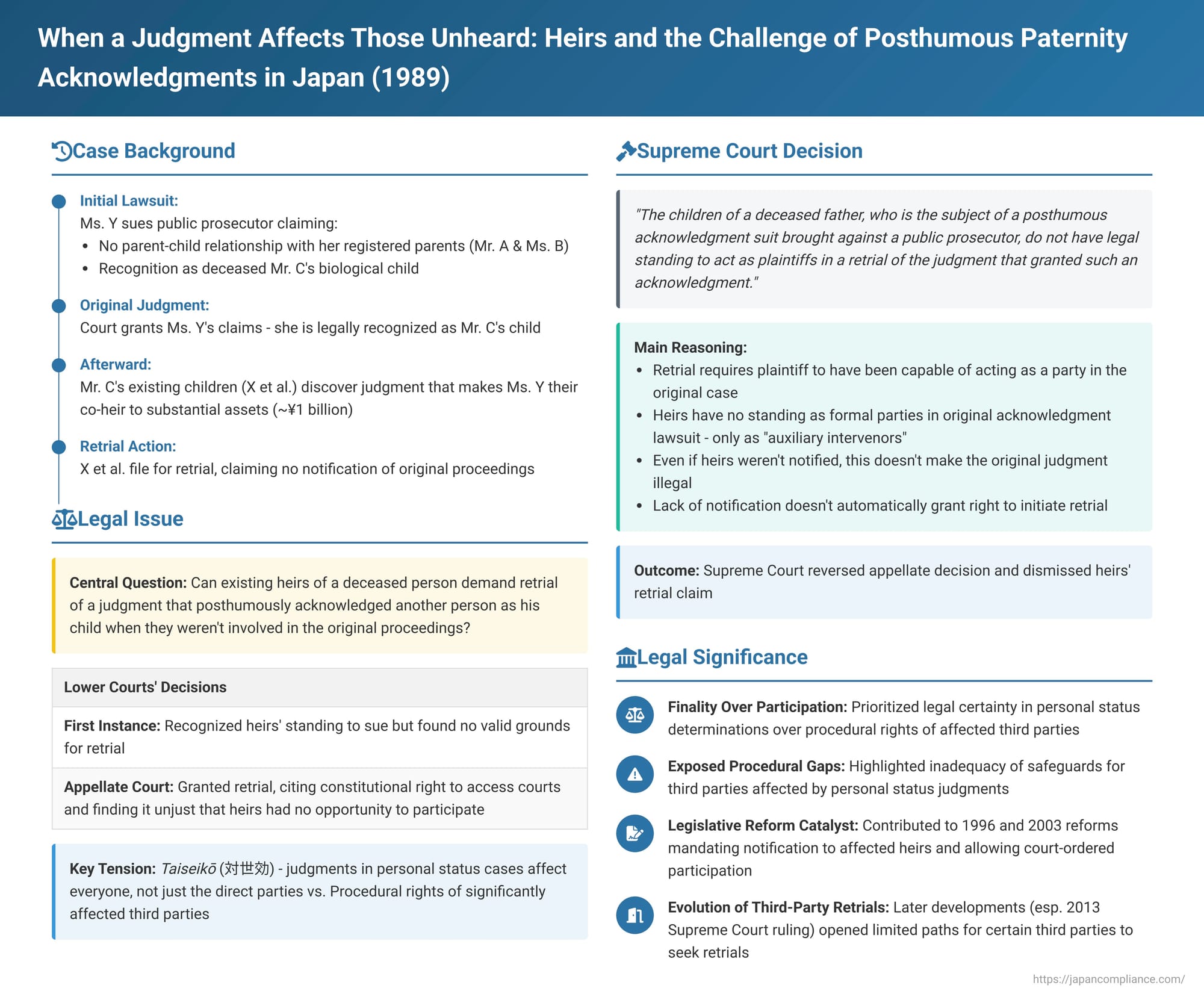

A pivotal 1989 Supreme Court decision grappled with a difficult intersection of family law, procedural rights, and the far-reaching effects of judgments that define legal parentage. The case, a "Retrial of Parent-child Relationship Non-existence Confirmation, etc. Claim Case" (親子関係不存在確認等請求再審事件), addressed whether existing heirs of a deceased man could demand a retrial of a judgment that posthumously acknowledged another person as his child, especially when those heirs were not involved in the original proceedings. The Court's negative answer highlighted the stringent conditions for reopening such cases and underscored the tension between the need for legal certainty in status matters and the procedural rights of significantly affected third parties.

The Original Lawsuit: A New Heir Recognized

The chain of events began with Ms. Y. According to her family register (koseki), Ms. Y was the child of the late Mr. A and the late Ms. B. However, Ms. Y asserted that her true biological father was a different deceased individual, Mr. C.

Consequently, Ms. Y initiated a lawsuit (the "original lawsuit" or zenso) naming the public prosecutor as the defendant. This is the standard procedure in Japan for seeking posthumous acknowledgment of paternity when the alleged father has passed away (Civil Code Article 787; current Personal Status Litigation Act Article 42(1)). Ms. Y’s original lawsuit sought two things:

- A confirmation that no legal parent-child relationship existed between her and Mr. A and Ms. B.

- A judicial acknowledgment that she was, in fact, the child of the late Mr. C.

In these original proceedings, the public prosecutor submitted a response stating no knowledge regarding the contested parent-child relationships but did not actively participate further—making no appearance at oral argument hearings nor submitting any evidence. Based solely on the evidence presented by Ms. Y, including witness testimony she had requested, the court ruled entirely in her favor, granting both the confirmation of non-paternity with A and B, and the acknowledgment of paternity by C. This judgment became final and legally binding.

The Retrial Action: Existing Heirs Challenge the New Reality

The late Mr. C had other children, Ms. X and her siblings (referred to collectively as "X et al."). They were existing legal heirs of Mr. C, who was reported to have possessed considerable assets, estimated at nearly one billion yen at the time of his death.

X et al. stated that they had received no notification of Ms. Y’s original lawsuit against the prosecutor, nor were they summoned as witnesses or contacted by the prosecutor about the matter. They remained entirely unaware of the proceedings until after the judgment acknowledging Ms. Y as Mr. C's child had become final.

Upon learning of the judgment, which significantly impacted their inheritance rights by introducing a new co-heir, X et al. filed for a retrial of the original lawsuit. They named both Ms. Y and the public prosecutor as defendants in their retrial action. Their claim was that the lack of notification and opportunity to participate constituted grounds for retrial by analogy to Article 420(1)(iii) of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure then in effect (a provision concerning situations where a party was prevented from presenting their case due to the actions of another party or a third person; similar to current Article 338(1)(iii)).

The first instance court handling the retrial acknowledged X et al.'s standing to sue but found no valid grounds for a retrial, dismissing their claim. However, the appellate court took a different view. It reasoned that, considering the constitutional right to access courts (Constitution Article 32) and the objective of personal status litigation to ascertain substantive truth, X et al. deserved a remedy. Since they were, without fault on their part, unaware of the original lawsuit and thus deprived of a chance to participate, the appellate court held they could contest the original judgment through a retrial, drawing an analogy to Article 34 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (which allows third parties whose rights are infringed by a judgment in an administrative case, and who couldn't participate for reasons not attributable to them, to seek a retrial). The appellate court also found grounds for retrial by analogy to the aforementioned Code of Civil Procedure provision and proceeded to annul the part of the original judgment that had acknowledged Ms. Y as Mr. C’s child. Ms. Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Stance: No Standing for Retrial for These Heirs

The Supreme Court reversed the appellate court's decision regarding the acknowledgment and, ruling directly, dismissed the retrial claim initiated by X et al. The Court's reasoning was as follows:

The children of a deceased father, who is the subject of a posthumous acknowledgment suit brought against a public prosecutor, do not have legal standing to act as plaintiffs in a retrial of the judgment that granted such an acknowledgment.

The Court elaborated:

- A retrial, as defined in the Code of Civil Procedure, is a comprehensive process aimed at canceling a final judgment and then re-examining the original claim. It is predicated on the assumption that the plaintiff seeking the retrial is someone who would have been capable of performing litigation acts (i.e., acting as a party) in the original case itself.

- However, under the Personal Status Litigation Procedure Act (the law governing such family law cases, both the old version applicable then and the current Personal Status Litigation Act Article 42(1)), the children of the deceased father (like X et al.) do not possess standing to be formal parties in the original acknowledgment lawsuit initiated by the claimant (like Ms. Y). Their involvement is limited to that of "auxiliary intervenors" (hojo sanka, 補助参加), meaning they can support one of the actual parties but cannot independently control the litigation or act as a main party.

- While it's true that a judgment in an acknowledgment suit has a broad effect, impacting third parties including these other children (a concept known as taiseikō, 対世効 – effect erga omnes, or on the world at large; provided for in old Personal Status Litigation Procedure Act Articles 32(1) and 18(1), now Personal Status Litigation Act Article 24(1)), this does not automatically confer retrial standing. Even if such children were, without any fault of their own, denied the opportunity to participate in an acknowledgment suit (whether against a living father or, as here, posthumously against a prosecutor), this lack of participation does not inherently render the original acknowledgment judgment illegal, nor does it grant them an automatic right to initiate a retrial. This principle holds true when the father is deceased and the prosecutor is the defendant.

- The Court acknowledged that in personal status litigation involving a prosecutor as the defendant, it is desirable for interested third parties to be given an opportunity for auxiliary participation to aid in the discovery of truth. However, litigation acts performed by the prosecutor are not considered legally flawed merely because such an opportunity for third-party participation was not provided.

- The Supreme Court also clarified that a prior precedent (a Showa 28, or 1953, decision) which had hinted at the possibility of third-party retrials should not be interpreted as broadly granting such standing.

- Finally, the Court rejected the appellate court's analogy to the Administrative Case Litigation Act. It stated that the legal relationships dealt with in administrative litigation are different from those in personal status litigation. Moreover, personal status litigation procedures lack a special provision akin to Article 22 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act, which allows a form of joinder for third parties whose rights are affected by a judgment and who might then be eligible for retrial under Article 34 of that Act.

Thus, X et al.'s attempt to overturn Ms. Y's acknowledgment via retrial was ultimately unsuccessful.

The Conundrum: Taiseikō vs. Third-Party Procedural Rights

This 1989 ruling brought into sharp focus the inherent tension in Japanese personal status litigation between the doctrine of taiseikō and the procedural guarantees for interested third parties.

- Taiseikō: Judgments in personal status cases (like marriage, divorce, parentage) have an effect on everyone, not just the parties directly involved in the lawsuit. This broad effect is justified by the societal need for clear, uniform, and stable determination of family relationships, which concern the interests of many individuals and the public good. An acknowledgment of paternity, once finalized by a court, legally establishes the father-child relationship, and this status is then generally unchallengeable by anyone. This differs from a voluntary acknowledgment out of court, the validity of which can be contested by interested parties (Civil Code Art. 786). A court-ordered acknowledgment is generally only undone through a retrial.

- The Impact on Third Parties: From the perspective of third parties like X et al., taiseikō means their legal rights—most notably inheritance rights—can be significantly altered by a lawsuit in which they had no voice or participation.

- (Imperfect) Safeguards: Japanese personal status litigation incorporates mechanisms intended to ensure the discovery of substantive truth, which indirectly serve to legitimize the broad effect of these judgments. These include the principle of ex officio inquiry (shokken tanchi shugi, 職権探知主義), where the court can investigate facts beyond what the parties present (Personal Status Litigation Act Art. 20), and the potential involvement of the public prosecutor as a representative of the public interest (PSLA Art. 23). The first instance court in the retrial case had even cited these mechanisms as a reason for denying the retrial.

However, there was a growing sentiment, particularly in academic circles leading up to the 1989 decision, that these safeguards were insufficient to protect third parties whose crucial interests were at stake. Scholars proposed various measures, such as mandatory notification or summons for significantly affected individuals, limitations on the extension of a judgment's effects to non-participants, or more accessible avenues for retrial.

Academic Reaction and the Push for Enhanced Guarantees

The 1989 Supreme Court decision was met with considerable criticism from legal scholars. It was often described as being "cold" or unsympathetic to the procedural plight of third parties, like X et al., whose inheritance rights were substantially diminished without any opportunity for them to be heard in the original proceedings. Even before the ruling, some legal practitioners had highlighted the potential for inadequate examination of facts in personal status cases where the prosecutor, often overburdened or lacking specific information, acts as a passive defendant, lending some understanding to the appellate court's attempt to provide a remedy through retrial.

Legislative and Judicial Evolution Since 1989

The issues highlighted by the 1989 case contributed to subsequent reforms aimed at bolstering procedural guarantees for third parties in personal status litigation.

1. Improved Notification and Participation (Post-1996 Reforms):

- The 1996 revision of the Code of Civil Procedure and the enactment of the current Personal Status Litigation Act in 2003 (Heisei 15) introduced important changes:

- Notification: Provisions were established requiring the court to notify individuals whose inheritance rights would be directly affected by the outcome of certain personal status lawsuits (initially in the old Personal Status Litigation Procedure Act Art. 33, now in PSLA Art. 28 and detailed in Personal Status Litigation Rules Art. 16 and its annexed table).

- Court-Ordered Participation: In personal status lawsuits where the public prosecutor is the defendant (such as posthumous acknowledgment cases), the court was empowered to, ex officio (on its own initiative), have third parties whose inheritance rights would be affected by the judgment participate in the proceedings (PSLA Art. 15(1)). This participation is akin to a "co-litigant-like auxiliary intervention," giving them more robust rights than simple auxiliary intervenors (PSLA Art. 15(3), (4)).

2. Limitations of Current Protections:

Despite these advancements, challenges remain:

- The scope of mandatory notification is generally limited to those whose inheritance rights are affected. It doesn't necessarily cover other significantly interested parties in different types of status litigation (e.g., the mother in a suit denying the husband's paternity of a child born in wedlock).

- Notification may not be deemed necessary if the primary individual with legal standing to sue or be sued is actively litigating the case.

- Notification is typically limited to cases where the names and addresses of these interested third parties are ascertainable from the court record (PSLA Art. 28 proviso). However, the Personal Status Litigation Rules (Art. 13) did expand the requirements for plaintiffs to submit family registers and other documents that might identify such parties.

- Crucially, these notification provisions are often interpreted as "instructive" (kunji kitei, 訓示規定) rather than mandatory in a way that would nullify a judgment if breached. Failure to notify, therefore, may not in itself be grounds to invalidate the judgment.

3. The Evolving Landscape of Third-Party Retrials:

The possibility of a third party seeking a retrial has also seen some development:

- The current Code of Civil Procedure (Art. 45(1)) clarifies that a third party who could have intervened as an auxiliary participant can file an application for retrial concurrently with an application to intervene.

- More significantly, a Supreme Court decision on November 21, 2013 (Heisei 25), opened a path for a third party whose rights are affected by a judgment to gain standing as a plaintiff in a retrial by filing an application for "independent party intervention" (dokuritsu tōjisha sanka, 独立当事者参加) alongside their retrial claim. This type of intervention is for parties whose own rights are directly prejudiced by the outcome of the original suit and who have a distinct claim related to the subject matter.

However, even these avenues have complexities:

- For auxiliary intervenors, the prevailing legal understanding is that they generally cannot use their own lack of procedural guarantees (e.g., not being notified or involved earlier) as a distinct ground for retrial. They are usually bound by the grounds available to the party they supported (a judicial opinion in a Supreme Court decision on July 10, 2014, supports this).

- For independent party intervenors, while they might have more scope to assert their own grounds for retrial, a key hurdle is establishing the "independent claim" necessary for such intervention. In cases like Ms. Y's posthumous acknowledgment, it is debated whether existing heirs (like X et al.) could formulate a qualifying independent claim (e.g., a counterclaim for a declaration of non-existence of a parent-child relationship between Ms. Y and Mr. C). Scholarly opinion is divided, though some suggest possibilities.

- The 2013 Supreme Court decision also recognized a retrial ground under Code of Civil Procedure Article 338(1)(iii) (related to misconduct or incapacitation affecting a party's representation) if the litigation conduct of an original party, who should have considered the interests of an affected third party, was so grossly contrary to good faith that extending the judgment's effect to the third party becomes unconscionable from a procedural guarantee perspective. Whether the often passive conduct of a prosecutor in posthumous acknowledgment suits would meet this high "grossly contrary to good faith" standard is questionable.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Quest for Balance

The Supreme Court's 1989 decision denying retrial standing to the existing heirs of Mr. C starkly illustrated the potential for hardship when the broad, societal need for finality in family status determinations clashes with individual procedural rights. While the ruling itself adhered to a strict interpretation of then-existing procedural limitations for third-party involvement in retrials, it catalyzed further discussion and eventual legislative reforms aimed at providing earlier notification and participation opportunities for those whose rights are significantly impacted by personal status litigation.

Despite these reforms, the path to redress for a third party who believes their rights were unfairly affected by a judgment in a case they did not participate in remains complex. The subsequent developments in allowing certain forms of intervention coupled with retrial claims offer potential avenues, but they come with their own stringent requirements and unresolved questions. The core challenge—balancing the taiseikō of status judgments with robust procedural fairness for all substantially affected individuals—continues to be a subject of legal debate and refinement in Japan.