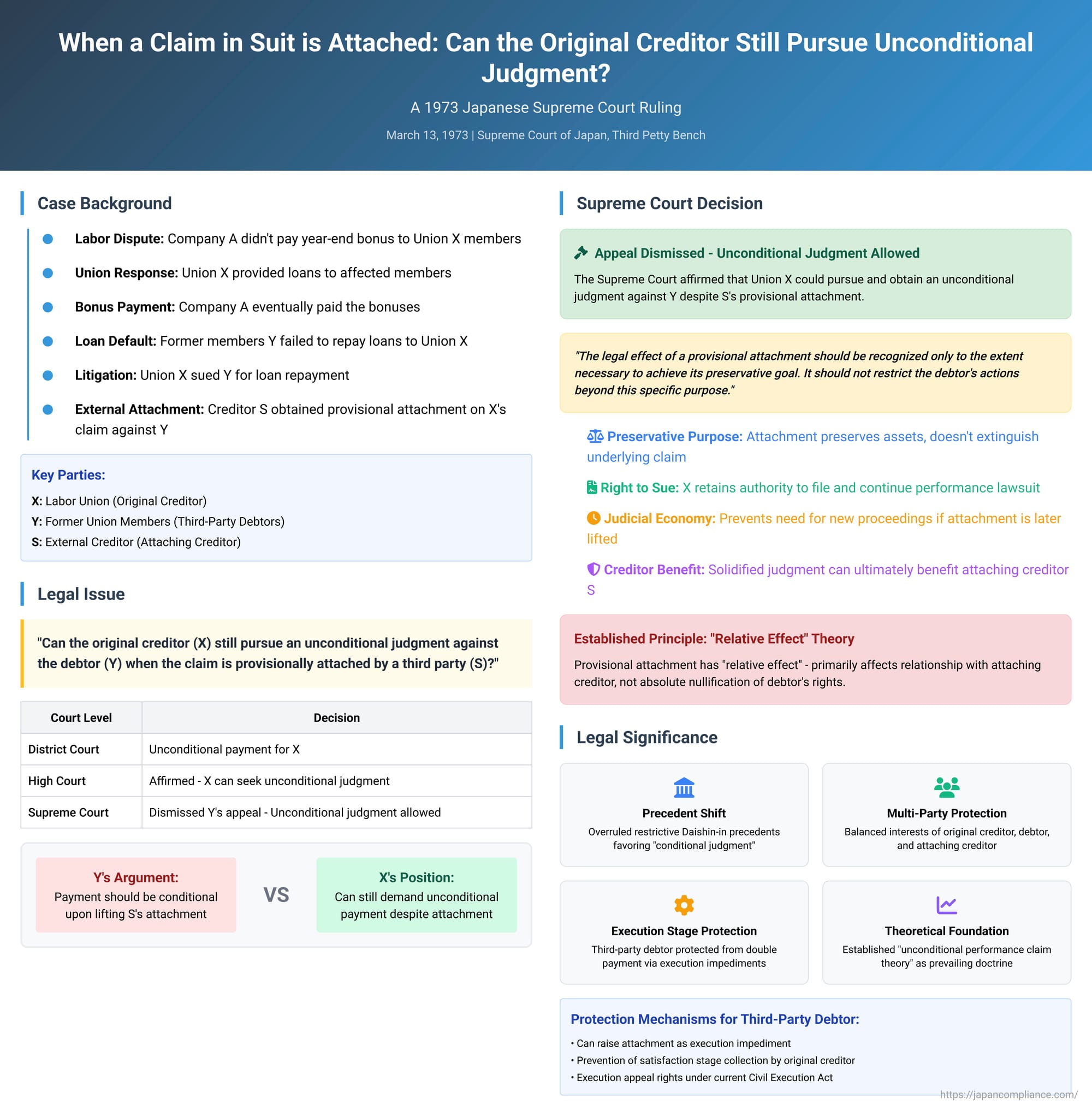

When a Claim in Suit is Attached: Can the Original Creditor Still Pursue Unconditional Judgment? Insights from a 1973 Japanese Supreme Court Decision

Date of Judgment: March 13, 1973

Case Name: Loan Repayment Claim Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: 1970 (O) No. 280

Introduction

Imagine a scenario: a creditor is in the process of suing a debtor for repayment. Suddenly, a third party—a creditor of the original creditor—steps in and obtains a provisional attachment on the very claim being litigated. Does this external event paralyze the ongoing lawsuit? Can the original creditor still demand full, unconditional payment from their debtor, or is their legal standing undermined by the attachment? This complex interplay of rights and procedures was the subject of a pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision on March 13, 1973. This ruling significantly clarified the extent to which a (provisional) attachment affects an existing lawsuit and the rights of all parties involved: the original creditor (whose claim is attached), their debtor, and the creditor who initiated the attachment.

The Factual Matrix: A Union, Its Members, and an External Attachment

The case revolved around the following parties and circumstances:

- X (Plaintiff/Appellee/Respondent): A labor union associated with Company A, possessing corporate legal status.

- Y (Defendants/Appellants/Appellants): A group of former members of Union X.

- S (External Creditor): An unnamed third party who held a claim against Union X for the return of deposited money.

- Company A: The employer of the union members.

The underlying dispute arose from a labor disagreement between Union X and Company A, which resulted in the company not paying a customary year-end bonus to the union members. To alleviate the financial hardship on its members, Union X provided them with loans. Subsequently, Company A did pay the year-end bonuses. However, certain former members (the Y defendants) failed to repay their loans to Union X. Consequently, Union X initiated a lawsuit against Y to recover the outstanding loan amounts.

A crucial development occurred while Y's appeal was pending before the Tokyo High Court: S, who had a separate monetary claim against Union X, successfully applied for and obtained a provisional attachment order. This order targeted the very loan repayment claims that Union X was pursuing against Y in the ongoing litigation.

Following this provisional attachment, Y argued in court that Union X could no longer seek an unconditional, immediate payment. Instead, Y contended that any payment obligation on their part should be conditional upon the lifting or release of S's provisional attachment.

The Journey Through the Lower Courts

- Court of First Instance (Yokohama District Court, Kawasaki Branch): This court ruled partially in favor of Union X, granting an unconditional order for Y to make the payment. Y, dissatisfied, appealed this decision.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court upheld the first instance judgment. It dismissed Y's argument that the provisional attachment should make X’s claim conditional. The High Court reasoned that a third-party debtor (like Y) in such a situation is merely empowered to prevent the execution proceedings (initiated by X based on a judgment) from reaching the "satisfaction stage" (i.e., actual collection by X) due to the existing provisional attachment by S. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that the High Court had misinterpreted the law regarding the effect of provisional attachments and had violated precedents set by the Daishin-in (the former Great Court of Cassation).

The Supreme Court's Definitive Stance

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on March 13, 1973, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's decision and establishing critical principles regarding the effect of provisional attachments on pending litigation.

The Court's reasoning was comprehensive:

- Purpose and Scope of Provisional Attachment:

The primary objective of a provisional attachment is to preserve the debtor's (here, X's) assets in their current state to secure the potential future execution of a monetary claim by the attaching creditor (S). Consequently, the legal effect of a provisional attachment should be recognized only to the extent necessary to achieve this preservative goal. It should not be interpreted as restricting the debtor's (X's) actions beyond this specific purpose. - Effect of Provisional Attachment on a Claim:

When a claim is provisionally attached:- The third-party debtor (Y, who owes money to X) is prohibited from making payment to the provisionally attached debtor (X).

- The provisionally attached debtor (X) is prohibited from collecting the claim from Y, or from assigning, transferring, or otherwise disposing of it.

However, the Supreme Court clarified that these prohibitions primarily mean that if X or Y act contrary to them, such actions cannot be asserted against the provisional attaching creditor (S). The attachment does not, in itself, strip X of its fundamental rights concerning the claim vis-à-vis Y.

- The Provisionally Attached Debtor's (X's) Right to Sue:

Crucially, the Court held that the provisional attachment does not divest the provisionally attached debtor (X) of the authority to:- File a performance lawsuit against the third-party debtor (Y) for the attached claim.

- Continue prosecuting such a lawsuit if it was already pending when the attachment occurred.

- Obtain an unconditional judgment for performance (i.e., a judgment ordering Y to pay X without conditions related to the attachment).

This interpretation allows the provisionally attached debtor (X) to secure an enforceable title (a judgment) against Y and to take necessary actions, such as interrupting the statute of limitations on the claim.

- Considerations of Judicial Economy:

The Court highlighted a practical problem with denying X the right to an unconditional judgment. If X were forced to lose its lawsuit against Y merely because S had provisionally attached the claim, and if S's provisional attachment were later canceled or withdrawn, X would be compelled to initiate entirely new legal proceedings against Y. This would be contrary to the principles of judicial economy. - Benefit to the Provisional Attaching Creditor (S):

Allowing X to pursue its claim against Y to judgment can indirectly benefit S. By X obtaining a judgment, the claim against Y is solidified and preserved, which ultimately aids S if S later proceeds to a final execution against X's assets (which include the claim against Y). - Protecting the Third-Party Debtor (Y) from Double Payment:

The Court addressed the legitimate concern that Y might face the risk of having to pay the same debt twice—once to X (based on the unconditional judgment) and potentially again to S (if S executes against the claim). The Court stated that Y has a protective mechanism: if X attempts to enforce the unconditional judgment, Y can demonstrate to the executing court or agency that the claim is subject to S's provisional attachment. This presentation acts as an "execution impediment," allowing the executing body to prevent the enforcement proceedings from progressing to the "satisfaction stage" (i.e., the actual collection of funds by X). The Court referenced Article 544 of the old Code of Civil Procedure (which has since been deleted and its principles incorporated elsewhere) as the basis for this. - Overruling Conflicting Precedents:

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that any Daishin-in precedents that conflicted with this new interpretation—specifically citing judgments from July 24, 1929 (Minshu Vol. 8, p. 728) and December 27, 1940 (Minshu Vol. 19, p. 2368)—should be changed. This marked a significant departure from older judicial thinking.

Applying this reasoning to the specific facts, the Supreme Court concluded that S's provisional attachment on X's claim against Y did not affect X's substantive or procedural right to seek unconditional payment from Y. The High Court's judgment was therefore correct.

Unpacking the Legal Landscape: Pre- and Post-1973

The 1973 Supreme Court decision was a watershed moment, resolving considerable debate and uncertainty.

Traditional Views (Pre-1973):

Before this judgment, the prevailing view, particularly under older Daishin-in precedents, was far more restrictive.

- One line of cases held that if a claim was attached, the original creditor (the attached debtor, like X) lost their standing (当事者適格, tōjisha tekikaku) to demand immediate payment, and their lawsuit was to be dismissed.

- Later precedents softened this slightly, allowing for a "conditional payment" judgment—for instance, ordering the third-party debtor (Y) to pay the original creditor (X) only if and when the attachment was lifted. Provisional attachments were treated similarly.

- Some academic theories supported these restrictive views, with some even suggesting that an attachment should lead to a suspension of the lawsuit, analogous to how bankruptcy proceedings could suspend litigation under the old Code of Civil Procedure, with the attaching creditor potentially taking over the suit later.

Criticism and the Emergence of the "Unconditional Performance Claim" Theory:

These traditional views faced growing criticism. Critics argued that:

- An attachment does not extinguish or substantively alter the underlying claim between the original creditor (X) and their debtor (Y). It primarily affects the claim's enforceability by X in a way that protects the attaching creditor (S). It should thus be viewed as an impediment arising at the execution stage, not as a bar to obtaining judgment.

- A provisional attachment, in particular, is merely a preservation measure. Maintaining the status quo of the attached asset (the claim) is its goal. Granting the third-party debtor (Y) a substantive defense against X’s lawsuit itself goes beyond this preservative purpose.

- Allowing the original creditor (X) to continue the suit and obtain judgment serves vital interests: it interrupts the statute of limitations, and it secures an enforceable title. This can also benefit the attaching creditor (S), who might later obtain an assignment order (転付命令, tenpu meirei) and directly execute based on the judgment X obtained.

These critiques fostered the "unconditional performance claim theory" (無条件給付請求説, mujōken kyūfu seikyū-setsu), which posited that the original creditor (X) could still sue for, and obtain, an unconditional judgment against their debtor (Y), despite the attachment. Some lower courts had begun to adopt this view even before the 1973 Supreme Court ruling.

Significance of the 1973 Supreme Court Judgment:

This judgment was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly endorsed the unconditional performance claim theory in the context of a provisionally attached claim. It did so by emphasizing the "relative effect" (相対的効力, sōtaiteki kōryoku) of the provisional attachment—meaning its effects are primarily asserted in the relationship with the attaching creditor (S), not by absolutely nullifying the attached debtor's (X's) rights against the third-party debtor (Y).

This position has since become the prevailing view in both case law and academic theory, even after the enactment of the current Civil Execution Act. Subsequent lower court decisions have, for example, allowed a provisionally attached debtor (X) to, in turn, seek an attachment order against assets belonging to the third-party debtor's (Y's) own debtors, based on the provisionally attached claim X holds against Y.

Navigating Competing Interests and Protecting the Third-Party Debtor

The 1973 judgment also addressed how to protect the third-party debtor (Y) from the risk of double payment.

Mechanisms for Protection:

The Supreme Court stated Y could raise the existence of S's provisional attachment during the execution phase of X's judgment against Y, thereby halting X's collection at the "satisfaction stage."

The protection for third-party debtors has evolved, particularly with the current Civil Execution Act:

- Assignment Orders (Tenpu Meirei): Under the old system, there was a risk: if X obtained an unconditional judgment against Y and then quickly obtained an assignment order for Y's other assets (as a means of collecting the judgment debt), Y might have limited means to object before the assignment became final, potentially leading to Y paying X, while still being liable to S regarding the original attached claim.

- The current Civil Execution Act provides stronger safeguards. An assignment order issued to X (to collect from Y) can be appealed by Y via an "execution appeal" (執行抗告, shikkō kōkoku) (Civil Execution Act Art. 159(4)). Furthermore, an assignment order does not become effective until it is final and unappealable (Art. 159(5)). Thus, if X, having obtained an unconditional judgment against Y, then seeks an assignment order against Y based on that judgment, Y can file an execution appeal, pointing to S's pre-existing attachment on the underlying claim, to prevent the assignment order in favor of X from taking effect.

- When X Tries to Further Attach Y's Assets: If X (the provisionally attached debtor) attempts to enforce their judgment against Y by, for example, attaching Y’s bank account, and Y is already aware that X's claim (which formed the basis of the judgment) is provisionally attached by S, the situation is complex. Lower courts have indicated that Y cannot necessarily use an execution appeal against X's attachment of Y's bank account by merely citing the risk of double payment stemming from S's attachment of X's original claim. However, a more accepted procedure is for the executing court handling X's enforcement against Y to suspend those enforcement proceedings if Y submits official documentation of S's provisional attachment order against X. This is treated analogously to the submission of documents that mandate a stay of execution under Civil Execution Act Art. 39(1)(vii) (see also Civil Execution Rules Art. 136(2)). Some lower court decisions have, in certain specific contexts, permitted an "execution objection" (執行異議, shikkō igi) by Y, though the precise procedural lines can be debated.

The Lingering Debate: Unconditional vs. Conditional Judgments

Despite the clarity provided by the 1973 Supreme Court decision, the debate over the fairest approach has not entirely disappeared.

- While the benefits to the original creditor (X) of obtaining an unconditional judgment—such as preserving the claim and interrupting prescription—are recognized, some argue that it places an undue burden on the third-party debtor (Y) to actively monitor and intervene at the execution stage to prevent double payment.

- The "conditional payment claim theory" (条件付請求権説, jōken-tsuki seikyūken-setsu) still holds some sway. Proponents argue that a judgment ordering Y to pay X on the condition that S's (provisional) attachment is lifted would adequately protect X's interests while being more considerate of Y's position.

- Another alternative discussed is for X to sue Y, demanding that Y deposit the disputed amount with a public depository (供託, kyōtaku) (as per Civil Execution Act Art. 156, Civil Preservation Act Art. 50(5)). However, if Y fundamentally disputes the existence or amount of the debt to X (as was the case here, at least initially), compelling Y to deposit the money might be inappropriate, especially before Y's liability to X is definitively established.

The Implications of Concurrent Lawsuits:

The 1973 judgment's logic also extends to situations where S (the attaching creditor) has obtained not just a provisional attachment but a "collection order" (取立命令, toritate meirei), allowing S to directly sue Y for the attached claim. Even in such cases, the prevailing view, following Supreme Court precedents, is that X (the original creditor) can still pursue their own lawsuit against Y and obtain a judgment for payment to X. If X's suit and S's collection suit against Y proceed concurrently, rules against duplicate litigation (Code of Civil Procedure Art. 142) might be applied by analogy to consolidate the hearings. (There remains academic discussion on whether a judgment in S's collection suit against Y would bind X).

A strong counter-argument, however, posits that once an attachment order (especially a final one with a collection order) is in place, X should be barred from all litigation activity concerning the attached claim.

Conclusion: Balancing Efficacy and Fairness

The Japanese Supreme Court's March 13, 1973 decision robustly affirmed that a provisional attachment on a claim does not, as a general rule, strip the original creditor of their right to sue their debtor and obtain an unconditional judgment for payment. The Court prioritized the need to preserve the original creditor's ability to secure their claim and interrupt prescription, while also recognizing that such actions could ultimately benefit the external attaching creditor.

However, this clear stance is balanced by procedural safeguards designed to protect the third-party debtor from the peril of double payment, primarily by allowing them to raise the attachment as an impediment at the enforcement stage. While the "unconditional judgment" approach is now firmly established, the ongoing academic discussion reflects the inherent complexities in perfectly balancing the interests of all three parties involved when a claim itself becomes the subject of an attachment. The ruling underscores that an attachment changes the dynamics of who can ultimately benefit from a claim, but not necessarily who can legally establish it in the first instance.