When a Birth Certificate Lies: Can a False Registration Create a True Adoption in Japan?

Judgment Date: April 8, 1975 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

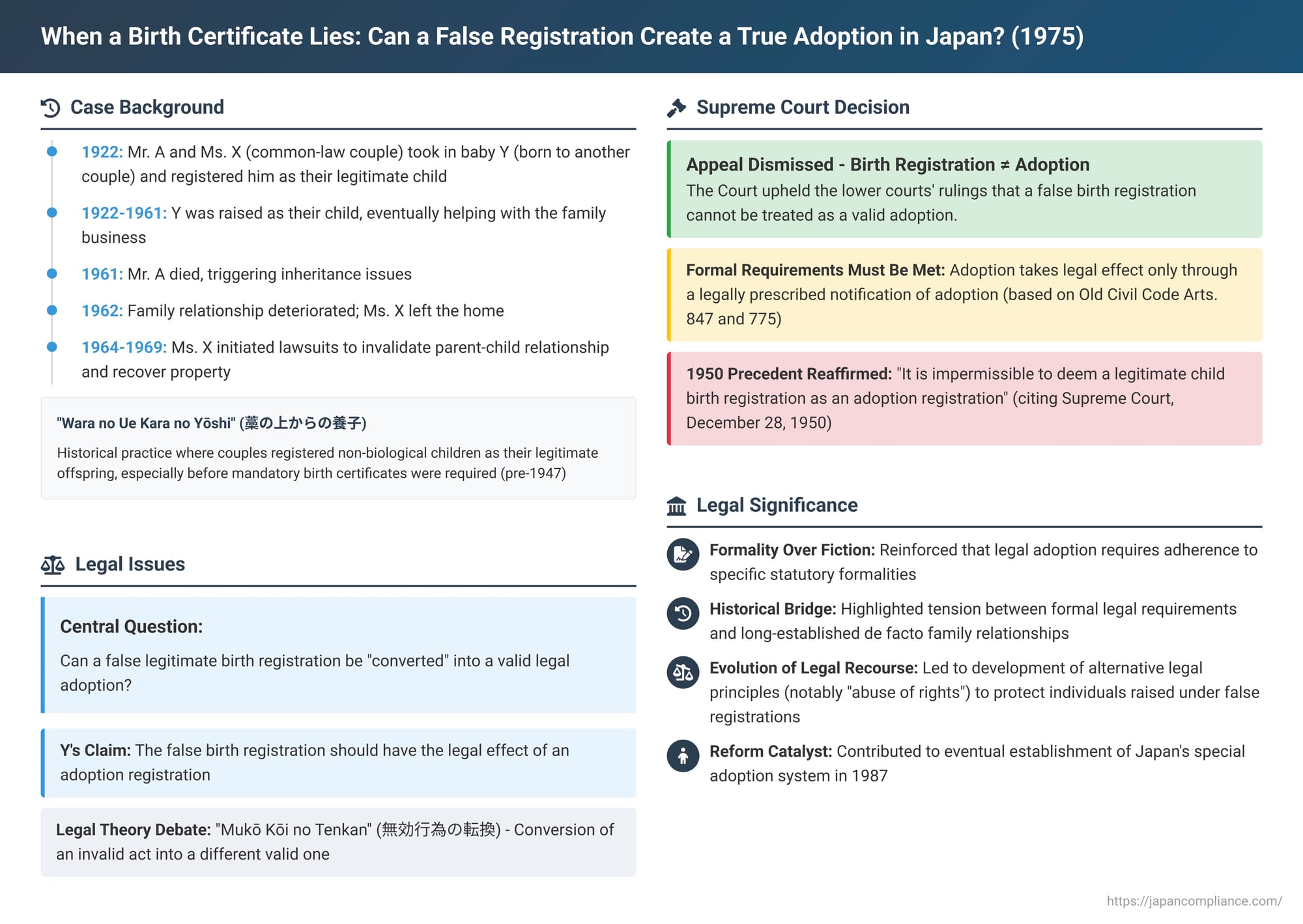

In a society where family records hold significant legal weight, what happens when a birth registration is knowingly falsified? Can such a document, intended to portray a child as the legitimate offspring of a couple who are not their biological parents, later be treated as if it were a valid adoption? The Japanese Supreme Court addressed this complex issue in a 1975 decision, reaffirming the strict formal requirements for establishing legal adoption and declining to allow a false birth certificate to be "converted" into an adoption. This case delves into a historical practice and a long-standing legal debate about balancing formal procedures with the realities of established family lives.

A Child Taken In, A Life Lived as Family: The Background

The case involved Mr. A and Ms. X, who lived together in a common-law marriage but were unable to have children of their own. In January 1922, a male child, Y (the defendant in this Supreme Court case), was born to another couple, Mr. and Mrs. B. Just two months later, in March 1922, Mr. A and Ms. X took the infant Y into their care and began raising him as their own.

In September 1922, Mr. A and Ms. X formalized their own relationship by registering their marriage. Simultaneously, they registered Y's birth, falsely declaring him as the legitimate child born to them. Y grew up in the household of Mr. A and Ms. X, eventually marrying and continuing to live with them while assisting in Mr. A's family business.

This arrangement continued until Mr. A passed away in November 1961, triggering inheritance proceedings. The family situation deteriorated thereafter. In April 1962, Ms. X and Y separated, with Ms. X alleging she was forced out of the home by Y.

The legal unravelling of Y's status began in 1964, when Ms. X filed a lawsuit against Y seeking a judicial declaration that no legal parent-child relationship existed between them (and by implication, between Y and the deceased Mr. A). In 1968, this lawsuit was concluded in Ms. X's favor, with a final judgment confirming the absence of a biological parent-child relationship.

Meanwhile, in 1966, Ms. X initiated the present lawsuit (later consolidated with another related claim) against Y. She sought the recovery of inherited property from Mr. A's estate, specifically the land and building where Y resided. In 1969, Y had registered an ownership transfer of this property based on inheritance laws, claiming a 2/3 share as Mr. A's "son," with Ms. X receiving 1/3 as the spouse (according to the statutory inheritance shares applicable before the 1980 Civil Code revision). Ms. X later sought to correct this shared ownership registration to reflect her as the sole owner.

Ms. X's primary argument in the current proceedings was that no parent-child relationship existed between Y and Mr. A (and herself). Y countered that even if there was no biological link, the legitimate child birth registration filed by Mr. A and Ms. X should be recognized as having the legal effect of an adoption registration, thereby establishing an adoptive parent-child relationship between Y and the late Mr. A (and Ms. X). As an alternative defense, Y argued that a de facto adoptive relationship had long existed, and therefore Ms. X's claims constituted an abuse of rights.

The first instance court ruled in favor of Ms. X. The Osaka High Court dismissed Y's appeal, reasoning that to treat a false legitimate birth registration as an adoption would improperly circumvent legal requirements, such as the need for Family Court permission to adopt a minor (Civil Code Art. 798). The High Court also stated that inheritance rights should be determined strictly based on official family register (koseki) entries, not on mere de facto relationships. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Stance: Formalities for Adoption Must Be Met

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions. This meant the false birth registration could not be treated as a valid adoption. The Court's key points were:

- Adoption Requires Specific Legal Notification: Referencing the Civil Code provisions in effect at the time of Y's birth registration (Old Civil Code Articles 847 and 775), the Court reiterated that an adoption takes legal effect only through a legally prescribed notification of adoption. It is impermissible to deem a legitimate child birth registration as an adoption registration. The Court cited its own 1950 precedent (Supreme Court, December 28, 1950) which had established this principle.

- Discussion of Current Law Not a Misapplication: Y had argued that the High Court improperly applied the current Civil Code's Article 798 (regarding court permission for minor adoptions) to this historical registration. The Supreme Court clarified that the High Court's mention of Article 798 was merely part of a general discussion on contemporary legal interpretation and not a direct, erroneous application to the old facts of this specific case.

- Parentage as a Preliminary Issue in Property Disputes: Y also contended that the parent-child relationship between himself and Mr. A should have been definitively settled by a court before any ruling on property rights. The Supreme Court dismissed this, stating that even in the absence of a final judgment specifically confirming or denying parentage, a court handling a property dispute (like the current inheritance recovery claim) is entitled to make a finding on the existence or non-existence of a parent-child relationship as a preliminary issue necessary to resolve the property claim. The Court cited its own 1964 precedents on this matter.

"Wara no Ue Kara no Yōshi" and the "Conversion of an Invalid Act" Theory

This case touches upon a historical Japanese practice known as "Wara no Ue Kara no Yōshi" (藁の上からの養子), literally "adoption from upon the straw." This term refers to the custom where a couple would take a newborn child from another family (often to ensure an heir or for other social reasons) and register the child as their own biological, legitimate offspring. This practice was particularly prevalent before and during the war, partly because the old Family Register Act did not mandate the attachment of a doctor's birth certificate to a birth notification, making false registrations easier. Such acts, however, constitute the crime of making false entries in official documents. The introduction of mandatory birth certificates in the revised 1947 Family Register Act aimed to curb this, but the problem persisted, as highlighted by later events like the "Dr. Kikuta Incident" in 1973 (involving a doctor issuing false birth certificates), which eventually contributed to the establishment of Japan's special adoption system in 1987.

Legally, the question arose whether such a false legitimate birth registration, which is invalid as a declaration of biological parentage, could be "converted" into a valid adoption. This implicates a legal doctrine known as "Mukō Kōi no Tenkan" (無効行為の転換 – conversion of an invalid act). This doctrine, generally found in the principles of civil law, allows an act that is invalid for its intended purpose to sometimes be given effect as a different type of valid act, provided certain conditions are met (e.g., if the parties would have intended the alternative valid act had they known of the original act's invalidity). Examples in Japanese family law include a secret will that fails to meet formal requirements possibly being treated as a valid holographic will, or, significantly, a false legitimate birth registration made by a biological father for his non-marital child being treated as a valid acknowledgment of paternity (a principle affirmed by the Supreme Court in 1978). The central issue in the 1975 case was whether this conversion doctrine could apply to transform a false birth registration into an adoption.

The Evolution of Legal Thought on False Registrations and Adoption

The legal system's approach to "Wara no Ue Kara no Yōshi" and similar false registrations has evolved:

- Daishin'in (pre-WWII Supreme Court): Initially, for registrations made before the Meiji Civil Code fully took effect, the Daishin'in recognized the customary nature of "Wara no Ue Kara no Yōshi" and treated such arrangements as valid adoptions. However, after the Civil Code mandated specific notification procedures for adoption, the Daishin'in changed its stance for registrations made under the new Code, refusing to recognize them as effective adoptions (e.g., a 1936 ruling).

- Post-WWII Supreme Court: The 1950 Supreme Court decision (cited in the present 1975 case) firmly established that adoption is a formal act requiring strict adherence to legal procedures, and thus a legitimate birth registration cannot be simply deemed an adoption. This formalistic approach was criticized by some scholars, like Professor Taniguchi Tomohei, who argued for interpretations that would limit suits seeking to nullify long-standing de facto parent-child relationships.

- The "Conversion Theory" Debate: Professor Wagatsuma Sakae, a highly influential scholar, noted the apparent inconsistency between the 1950 ruling and a 1952 Supreme Court decision (which, under complex facts involving ratification by the adoptee, upheld an adoption initially based on an irregular process following a false birth registration). He proposed that the "conversion of an invalid act" theory should be used to recognize an adoptive relationship in "Wara no Ue Kara no Yōshi" cases to achieve substantive justice. This theory gained considerable academic support for a time, and some lower courts even adopted it. However, a subsequent Supreme Court decision in 1974 overturned a High Court ruling based on conversion, leading to a decline in the theory's popularity among scholars. Critics argued that with changes like mandatory birth certificates and the creation of the special adoption system, the practical need for such a conversion theory had diminished.

- The Rise of "Abuse of Rights": As the conversion theory lost traction, courts began to employ general legal clauses, such as the doctrine of "abuse of rights" (権利濫用, kenri ranyō) or the principle of good faith, to prevent unjust outcomes. This approach aims to stop parties (especially those who participated in the original false registration) from later challenging a long-established de facto parent-child relationship if doing so would be grossly unfair to the individual who was raised as a child of the family. A 1997 Supreme Court supplementary opinion hinted at this approach, and in 2006, the Supreme Court explicitly adopted the abuse of rights doctrine to protect an individual's status in a case involving a false birth registration, even while implicitly (or explicitly in the lower court ruling it affirmed on that point) rejecting the conversion-to-adoption argument.

Why "Conversion to Adoption" Was Denied in 1975

The 1975 Supreme Court decision in Mr. A, Ms. X, and Y's case reaffirmed the formalistic view established in 1950. The Court did not accept Y's argument that the false birth registration should be treated as an adoption. The primary reason was that adoption law, both at the time of Y's registration and under subsequent revisions, requires specific formalities and intent directed towards creating an adoptive relationship, not merely a biological one. A birth registration, by its nature, declares a biological (legitimate) birth, which is a different legal act with different premises and consequences than an adoption. To allow conversion would, as the High Court noted, risk circumventing other important legal safeguards, such as the (then-nascent, now more developed) requirement for court oversight in the adoption of minors.

While Y raised the defense of "abuse of rights" based on the de facto parent-child relationship, the Supreme Court in 1975 did not prominently engage with this argument in its reasoning for dismissing Y's appeal on the adoption point. Its focus was squarely on the legal impossibility of converting a birth registration into an adoption. The development of the abuse of rights doctrine as a primary tool to protect individuals in Y's situation would come more fully in later Supreme Court jurisprudence, notably the 2006 decision.

Current Standing of the "Conversion to Adoption" Theory

The Supreme Court has consistently refrained from adopting the theory that a false legitimate birth registration can be legally converted into a valid adoption. The 1975 decision is a cornerstone of this stance. The primary obstacle remains the significant difference in legal requirements and intentions between declaring a biological birth and undertaking a legal adoption. Practical difficulties, such as how such a "converted" adoption would be accurately reflected in the formal family register system, also pose challenges that would likely require legislative solutions rather than just judicial interpretation.

However, the academic debate around the conversion theory played a crucial historical role. It powerfully highlighted the potential for profound injustice when individuals raised within a family under a false registration face the loss of their legal status decades later. This intellectual pressure arguably contributed to the judiciary's eventual embrace of alternative equitable doctrines, like abuse of rights, to achieve fairer outcomes in these difficult cases.

Conclusion: Formalities Upheld, but Justice Sought Through Other Means

The 1975 Supreme Court decision in the case of Y firmly upheld the principle that legal adoption in Japan requires adherence to specific statutory formalities and that a false birth registration cannot be judicially "converted" into a valid adoption. This ruling underscored the importance of distinct legal acts and procedures within family law.

While the path of "conversion to adoption" was closed off, the Japanese legal system has, particularly in subsequent decades, increasingly utilized other legal principles, most notably the doctrine of abuse of rights, to protect individuals who have lived their lives under the assumption of a parent-child relationship based on such false registrations. This reflects an ongoing effort to balance the need for legal certainty and formal correctness with the imperative to achieve substantive justice and protect established familial bonds from belated and unfair disruption. The 1975 decision, therefore, is an important chapter in this evolving legal narrative, clarifying one specific legal question while implicitly setting the stage for other equitable solutions to emerge.