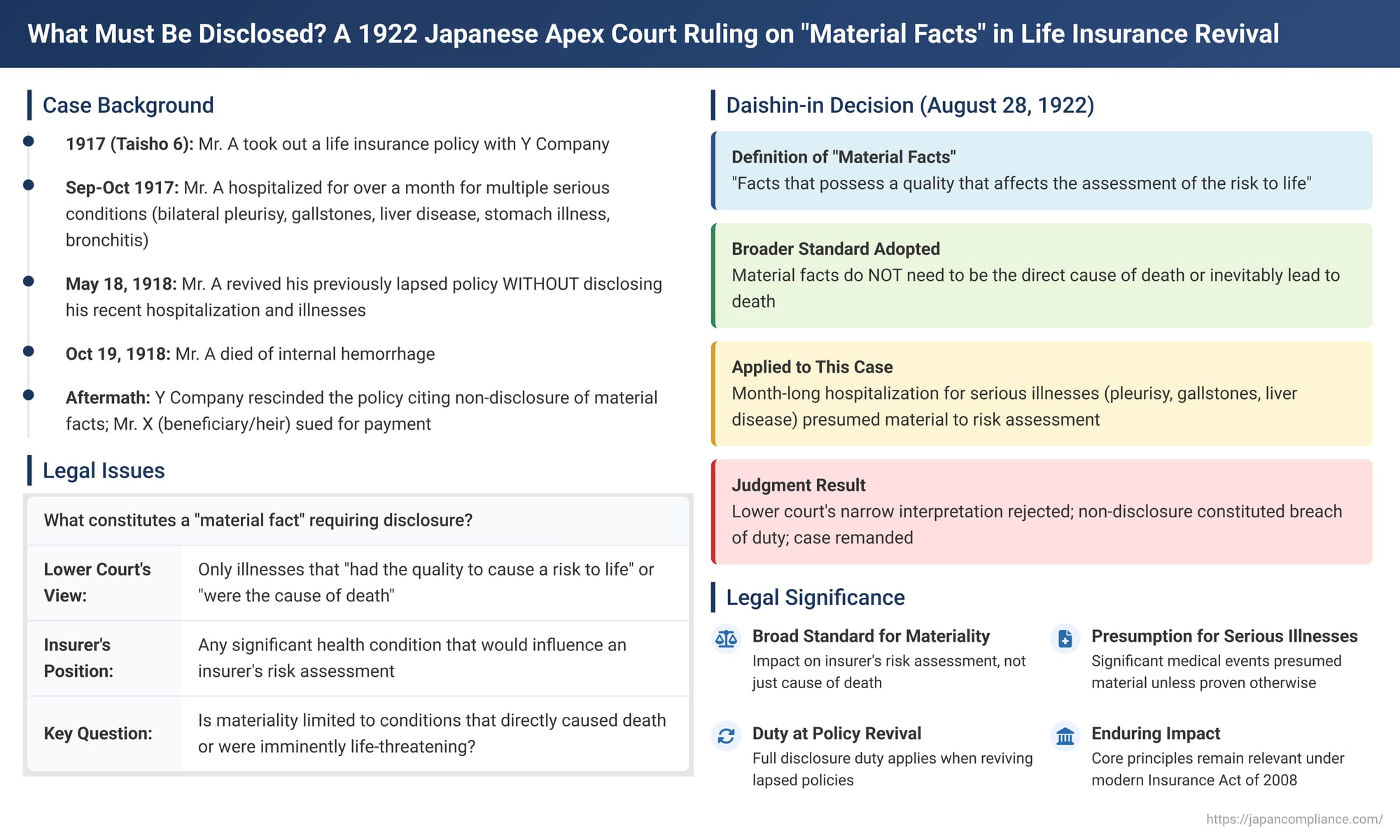

What Must Be Disclosed? A 1922 Japanese Apex Court Ruling on "Material Facts" in Life Insurance Revival

Judgment Date: August 28, 1922

Court: Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), Second Civil Department

Case Name: Insurance Claim Case

Case Number: Taisho 11 (O) No. 395 of 1922

Introduction: The Bedrock of Disclosure in Life Insurance

Life insurance contracts are fundamentally based on a principle of utmost good faith between the insurer and the insured. A cornerstone of this principle is the "duty of disclosure" (告知義務 - kokuchi gimu) imposed upon the person applying for insurance and/or the person whose life is to be insured. This duty requires them to provide truthful and complete information to the insurance company regarding factors that are material to the insurer's assessment of the life risk being undertaken. Such information, particularly concerning health and medical history, allows the insurer to make an informed decision about whether to issue a policy, and if so, on what terms and at what premium.

A failure to disclose "material facts" (重要ナル事実 - jūyō naru jijitsu), or the making of untrue statements about such facts, can have severe consequences, potentially giving the insurer the right to later rescind the contract and deny a claim, even if the non-disclosed condition was not the ultimate cause of death. This issue becomes particularly pertinent when a life insurance policy that has previously lapsed (e.g., due to non-payment of premiums) is sought to be revived. At the point of revival, the duty of disclosure essentially applies anew regarding the insured's health status.

But what exactly constitutes a "material fact" that must be disclosed? Does a past illness only become "material" if it was the direct cause of the insured's eventual death, or if it was demonstrably life-threatening at the time the disclosure should have been made? Or does the concept of materiality encompass a broader range of health conditions that would reasonably influence an insurer's underwriting judgment? This fundamental question was addressed by the Daishin-in, Japan's highest court at the time (the predecessor to the modern Supreme Court), in a significant and foundational ruling in 1922.

The Facts: A Lapsed Policy, Intervening Illnesses, and Non-Disclosure at the Time of Revival

The case involved Mr. A, who had initially taken out a life insurance policy on his own life with Y Life Insurance Company. This policy subsequently lapsed for reasons not detailed in the judgment summary.

Crucially, during the period between the original contract's inception (January 30, Taisho 6, or 1917) and its later revival, Mr. A experienced a significant bout of ill health. From September 4, Taisho 6 (1917), for over a month, he was hospitalized at Okayama Hospital. His medical conditions were serious and multiple: he was diagnosed with bilateral pleurisy (inflammation of the lining of the lungs) and gallstones, and these were accompanied by liver disease, stomach illness, and bronchitis. After being discharged from the hospital on October 8, 1917, Mr. A continued to receive treatment as an outpatient until the end of October of that year.

On May 18, Taisho 7 (1918), approximately seven months after his hospitalization ended, Mr. A entered into an agreement with Y Life Insurance Company to revive his previously lapsed life insurance policy. At the time of this policy revival, Mr. A did not disclose to Y Company the details of his recent serious illnesses and his month-long hospitalization.

A few months later, on October 19, Taisho 7 (1918), Mr. A died. The cause of death was stated as an internal hemorrhage.

The life insurance policy originally issued to Mr. A (and presumably the terms of its revival) contained a clause. This clause stipulated that if the insured person, either at the time of the original contract or at the time of a subsequent revival of a lapsed contract, failed to disclose important facts, or made untrue statements about important matters, Y Life Insurance Company had the right to rescind (cancel) the contract.

Upon Mr. A's death, when a claim was presumably made by his heir or beneficiary (Mr. X, the plaintiff in the lawsuit), Y Life Insurance Company invoked this clause. The company rescinded the revived policy on the grounds that Mr. A had concealed his significant pre-existing conditions (his recent hospitalization and the diagnosed illnesses) at the time the policy was revived.

Mr. X then sued Y Life Insurance Company, seeking payment of the insurance benefits.

The Core Legal Issue: What Constitutes a "Material Fact" Requiring Disclosure at Policy Revival?

The central legal dispute revolved around the definition and application of "material facts" in the context of the duty of disclosure for life insurance, particularly at the point of policy revival:

- Were the illnesses that Mr. A suffered between the original policy inception and its revival – including bilateral pleurisy, gallstones, liver disease, stomach problems, bronchitis, and a hospitalization lasting over a month – "material facts" that he was legally obligated to disclose to Y Insurance Company when he applied to revive the policy?

- More specifically, does a past illness or medical condition only become "material" for disclosure purposes if it can be shown to have directly caused the insured's subsequent death, or if it was of such a nature as to be imminently life-threatening at the time the disclosure should have been made?

- Or, does the concept of "materiality" encompass a broader range of health conditions and medical history if that information would reasonably affect a prudent insurer's assessment of the risk to the insured's life and, consequently, influence its decision on whether to revive the policy, or the terms (such as the premium) upon which it would do so?

The Lower Court's Ruling: Non-Disclosed Illnesses Deemed Not "Material"

The appellate court (referred to as the "original judgment" from which the appeal to the Daishin-in was made) had ruled in favor of Mr. X, the claimant. That court had found that Mr. A's undisclosed pre-existing conditions were not material facts requiring disclosure. Its reasoning was that these illnesses "did not have the quality (素質 - soshitsu) to cause a risk to life, nor were they the [direct] cause of [Mr. A's subsequent] death." Because the lower court deemed the undisclosed facts non-material, it held that Y Life Insurance Company's rescission of the revived policy was invalid, and the insurer was therefore obligated to pay the claim.

Y Life Insurance Company appealed this decision to the Daishin-in.

The Daishin-in's Decision (August 28, 1922): Adopting a Broader Definition of "Material Fact"

The Daishin-in, Japan's highest court at the time, overturned the lower court's decision. It found that the lower court had erred in its interpretation of "material facts" and remanded the case for further consideration.

Defining "Material Facts" for the Purpose of Disclosure

The Daishin-in began by addressing the legal meaning of "material facts" that an insured person is obligated to disclose under Article 429 of the (then-current) Commercial Code:

- It ruled that "material facts" are "facts that possess a quality (or nature/disposition - 素質 soshitsu) that affects the assessment of the risk to life" (生命ノ危険ヲ測定スルニ付影響アル素質ヲ有スル事実 - seimei no kiken o sokutei suru ni tsuki eikyō aru soshitsu o yūsuru jijitsu).

- Crucially, the Daishin-in explicitly stated that such material facts do not necessarily have to be conditions that were the direct cause of the insured's subsequent death. Nor do they have to be of a nature that would inevitably lead to death at the time the disclosure should have been made.

- The Court clarified that the term "material facts" as used in the specific clause of the insurance policy in this case (which allowed rescission for non-disclosure) should be interpreted as having the same meaning as this statutory definition.

Application of this Definition to Mr. A's Undisclosed Illnesses

The Daishin-in then applied this broader definition of "material facts" to the specific medical history of Mr. A that had not been disclosed at the time of the policy revival:

- It reiterated the facts as found by the lower court: Mr. A had, prior to the policy revival, suffered from an enlarged liver and mild jaundice (July 1917). He was subsequently hospitalized at Okayama Hospital from September 4 to October 8, 1917 (over a month). The primary diagnoses during this hospitalization were bilateral pleurisy and gallstones, and these were accompanied by liver disease, stomach illness, and symptoms of bronchitis. He continued to receive treatment as an outpatient until the end of October 1917.

- The Daishin-in reasoned that even if it were assumed that Mr. A's prognosis was considered good after his discharge from the hospital, and even if his eventual death (from an internal hemorrhage in October 1918) was not directly caused by these specific prior illnesses, a history of such significant and multiple illnesses requiring extended hospitalization (over a month for conditions like liver disease, pleurisy with complications including bronchitis, and gallstones) is presumed to possess a quality that affects an insurer's assessment of the risk to the insured's life.

- This presumption of materiality applies unless there is strong counter-evidence proving that these illnesses were, in fact, extremely minor in degree and posed no significant hazard to the insured's life expectancy from an objective underwriting perspective. (The Daishin-in noted that no such counter-evidence appeared to have been established in this case).

Conclusion on Mr. A's Breach of the Duty of Disclosure

Therefore, the Daishin-in concluded that Mr. A's failure to disclose this serious medical history at the time he applied to revive his life insurance policy constituted a failure to disclose material facts. This was a breach of his contractual duty of disclosure.

The Lower Court's Error

The Daishin-in found that the lower court had erred in its judgment. By ruling that Mr. A's prior illnesses were not material simply because they "did not have the quality to cause a risk to life, nor were they the cause of death," the lower court had either:

- Misunderstood the correct legal definition of "material facts" (by too narrowly restricting it only to conditions that were demonstrably and directly life-threatening at the time or were the ultimate cause of death), or

- Provided insufficient reasoning for its conclusion that these serious and multiple illnesses were not material.

The Daishin-in found that the insurer's grounds for appeal were valid. The judgment was therefore reversed, and the case was remanded for further proceedings consistent with the Daishin-in's interpretation of "material facts."

Analysis and Implications of this Foundational Ruling

This 1922 Daishin-in judgment, despite its considerable age, remains a foundational and frequently cited case in Japanese life insurance law. It played a crucial role in establishing a broad and arguably insurer-protective standard for what constitutes a "material fact" that an applicant or insured must disclose to a life insurer.

1. Establishing a Broad Standard for "Materiality" in Life Insurance Disclosure:

The most significant impact of this decision was its clarification that the "materiality" of a fact for disclosure purposes in life insurance is not limited to conditions that are imminently fatal or that turn out to be the direct cause of the insured's subsequent death. The standard is broader than that.

2. The "Risk Assessment Impact" as the Key Criterion for Materiality:

The central criterion for determining materiality, as articulated by the Daishin-in, is whether the undisclosed fact is something that would affect a prudent insurer's assessment of the risk to the insured's life. If knowledge of the fact would reasonably influence an insurer's decision-making process regarding whether to accept the risk at all, or on what terms it would accept the risk (for example, whether to charge a standard premium, impose a higher rated premium, add specific exclusions, or decline coverage altogether), then that fact is generally considered to be "material."

3. Strong Presumption of Materiality for Serious Illnesses and Extended Hospitalizations:

The judgment effectively creates a strong presumption that a history of serious illnesses, particularly those requiring extended periods of hospitalization (such as Mr. A's month-long stay for a combination of significant ailments like pleurisy, gallstones, and liver disease), is indeed material to an insurer's risk assessment. The burden would then effectively shift to the claimant (the beneficiary or heir) to provide compelling counter-evidence that such conditions were, in fact, so trivial or insignificant as to have absolutely no bearing on a reasonable insurer's assessment of the life risk, if they wished to argue that the non-disclosure was not of a material fact.

4. Explicit Rejection of a Narrow "Cause of Death" or "Imminently Life-Threatening" Test for Materiality:

The Daishin-in very clearly and explicitly rejected the lower court's much narrower approach, which seemed to require that an undisclosed illness must either be the direct cause of the insured's subsequent death, or be of an imminently life-threatening nature at the time the disclosure should have been made, in order to be considered "material." The Daishin-in's ruling established that even past medical conditions that may not be the direct cause of the ultimate death, or that might not appear immediately life-threatening at the moment of application or revival, can still be highly material if they would genuinely influence a prudent insurer's overall assessment of the risk to the insured's life and longevity.

5. Reinforcing the Duty of Disclosure at the Time of Policy Revival:

This case also serves as an important reminder that the duty of disclosure applies with full force not only at the time a life insurance policy is originally taken out but also at the time a previously lapsed policy is sought to be revived or reinstated. The insured person must disclose any material changes in their health status or any new material medical facts that have arisen since the original policy inception or since any previous renewal or revival. The insurer is entitled to make a fresh underwriting assessment based on the insured's current health condition at the time of revival.

6. Historical Context and Subsequent Legal Developments in Japan:

It is important to place this 1922 judgment in its historical context. It was decided under Japan's old Commercial Code. Japan subsequently enacted a comprehensive, standalone Insurance Act in 2008, which came into full effect in 2010. This modern Insurance Act now provides the primary statutory framework for insurance contracts.

- The Insurance Act of 2008 (in Article 37, for example) codifies the duty of disclosure. However, it introduced a significant structural change: the duty of disclosure is now primarily framed as a duty to truthfully answer specific questions asked by the insurer during the application process (this is often referred to as a "question-response duty" - 質問応答義務, shitsumon ōtō gimu). This is somewhat different from the system under the old Commercial Code, which was often interpreted as imposing a more spontaneous duty on the applicant/insured to disclose all material facts, whether specifically asked about or not.

- Despite this change in the procedural nature of the disclosure duty (from largely spontaneous to primarily responsive), the underlying concept of what constitutes "material matters" (重要な事項 - jūyō na jikō) remains absolutely central to the new Insurance Act. The Act defines these as matters that are relevant to assessing the possibility of the insured event (such as the death of the insured in a life insurance policy) occurring.

- Therefore, the fundamental reasoning of the Daishin-in in this 1922 case – particularly its core holding that "materiality" hinges on those factors that would genuinely affect an insurer's assessment of the risk being underwritten – continues to hold considerable persuasive value and provides important historical context for understanding what types of information are considered crucial in the underwriting of life insurance policies in Japan, even under the current legal framework.

- The specific factual finding in this case – that a history of a month-long hospitalization for a combination of serious ailments like pleurisy, gallstones, and liver disease is presumptively material – would very likely still be viewed similarly by insurers and courts today. Such a medical history would undoubtedly prompt specific questions from an insurer during the application or revival process, and a failure to truthfully answer those questions would trigger the remedies available to the insurer under the current Insurance Act (such as rescission of the contract under Article 55, subject to certain conditions and time limits).

7. The Insurer's Fundamental Right to Make an Informed Underwriting Decision:

The underlying principle that this Daishin-in judgment robustly supports is the insurer's fundamental right to be able to make its underwriting decision – whether to accept a risk, what premium to charge, and what terms and conditions to apply – based on a full, frank, and truthful disclosure of all facts that are material to that decision. Non-disclosure of significant adverse medical history, as occurred in this case at the time of policy revival, deprives the insurer of that essential opportunity and can, as the Daishin-in found, justify the insurer's subsequent decision to rescind the contract.

Conclusion

The August 28, 1922, decision by the Daishin-in in this life insurance case was a foundational judgment in Japanese insurance law. It provided a crucial and enduring clarification regarding the scope of an insured person's duty of disclosure, particularly in defining what constitutes a "material fact" that must be revealed to the insurer, especially when an application is made to revive a previously lapsed policy.

The Daishin-in established that "material facts" in the context of life insurance are those facts that possess a quality capable of affecting an insurer's professional assessment of the risk to the life being insured. This definition is significantly broader than just those conditions that are the direct cause of the insured's subsequent death or that are imminently life-threatening at the time the disclosure should have been made.

The Court made it clear that a significant history of illness, especially one involving extended hospitalization for multiple serious conditions, is presumptively considered material. The failure to disclose such a history at the time of policy revival constitutes a breach of the duty of disclosure, which can entitle the insurer to rescind the contract.

This early 20th-century ruling powerfully underscored the importance of transparency and completeness in the information provided during the insurance application and revival process. It affirmed the insurer's fundamental right to make informed underwriting decisions based on a comprehensive picture of the risks associated with the life being proposed for insurance. While Japanese insurance law has been substantially modernized with the enactment of the Insurance Act of 2008, the core principle that materiality is determined by a fact's impact on an insurer's risk assessment remains a vital concept in life insurance underwriting and law today.