What Makes Company Property "Important"? A Japanese Supreme Court Test for Board Approval in Asset Sales

Case: Action for Confirmation of Shareholder Rights

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of January 20, 1994

Case Number: (O) No. 595 of 1993

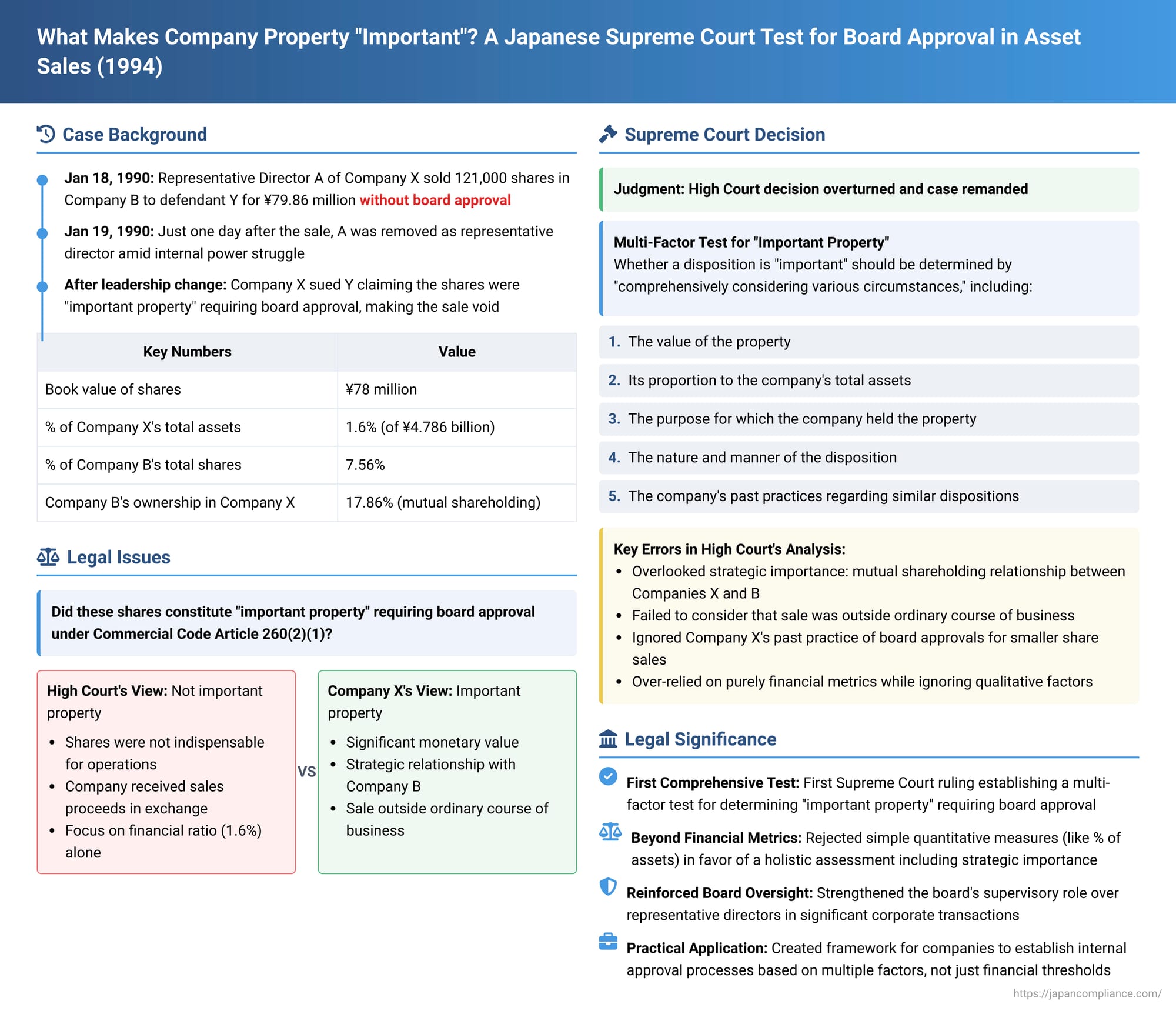

In Japanese corporate governance, while a representative director is empowered to conduct the company's day-to-day business, certain significant actions are reserved for the collective deliberation and approval of the board of directors. One such critical area is the "disposition of important property" (重要な財産の処分 - jūyō na zaisan no shobun). Selling off a major asset without board consensus can have profound implications for a company's future. But what exactly elevates a piece of property to the status of "important," thereby mandating board approval for its sale? A landmark Supreme Court decision on January 20, 1994, provided a comprehensive multi-factor test to guide this determination, moving beyond simple quantitative measures.

A Disputed Share Sale Amidst Corporate Turmoil: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, Company X, found itself embroiled in a legal battle to reclaim shares it contended were sold improperly. The shares in question were 121,000 shares of another company, Company B, which Company X owned.

The sale occurred on January 18, 1990. On this date, A, who was then the representative director of Company X, sold these shares in Company B to Y (the defendant) for a price of 79.86 million yen. Crucially, this significant share transaction was executed without a resolution of approval from Company X's board of directors.

The backdrop to this sale was a period of internal strife within Company X. The company had historically been controlled by the family of A. However, an internal power struggle had erupted between A and another individual, C. In 1989, A had become the representative director, and C had been removed from that position. This situation was short-lived. Following a settlement between the factions, on January 19, 1990 – merely one day after A had sold the Company B shares to Y – A was removed as representative director, and C was reinstated to that role.

Under C's new leadership, Company X filed a lawsuit against Y, the purchaser of the shares. Company X sought a legal declaration that it was still the rightful owner and shareholder of the Company B shares. The core of its argument was that the sale of these shares constituted a "disposition of important property" as defined by Article 260, Paragraph 2, Item 1 of the then-Commercial Code (a provision analogous to Article 362, Paragraph 4, Item 1 of the current Companies Act). As such, the sale required a resolution of approval from Company X's board of directors. Since no such resolution had been passed, Company X contended that the sale to Y was void.

The High Court's Narrow Focus on Financial Materiality

The Tokyo High Court, which heard the case on appeal, ruled against Company X. While acknowledging that the Company B shares had a considerable monetary value, the High Court focused on several factors to conclude they were not "important property" in the legal sense requiring board approval:

- The shares were not indispensable for Company X's ongoing business operations; Company X's primary interaction with these shares was merely receiving dividends.

- Company X had received sales proceeds in exchange for the shares.

- The book value of the Company B shares was compared to Company X's total assets, and the ratio was presumably not deemed sufficiently high on its own. (The Supreme Court later noted the book value of the shares was 78 million yen, representing about 1.6% of Company X's total assets of approximately 4.786 billion yen).

Based on this assessment, the High Court determined that the sale did not fall under the category of "disposition of important property" and thus did not require a board resolution. Company X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Broader Framework: Overturning and Remanding

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings, finding that the High Court's analysis of what constitutes "important property" was insufficient and too narrow.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: A Comprehensive Multi-Factor Test

The Supreme Court laid down a comprehensive test for determining whether a disposition of property qualifies as "important" under the statute, thereby necessitating a board resolution. It stated:

"Whether a disposition falls under 'disposition of important property' as stipulated in Article 260, Paragraph 2, Item 1 of the Commercial Code should be judged by comprehensively considering various circumstances, including:

- The value of the said property.

- Its proportion to the company's total assets.

- The purpose for which the company held the property.

- The nature and manner of the disposition (e.g., sale, gift, terms).

- The company's past practices regarding similar dispositions."

Applying this multi-factor test to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its conclusion:

- Value and Proportion: While the book value of the Company B shares was approximately 78 million yen, constituting about 1.6% of Company X's total assets, the Supreme Court indicated this ratio was not, by itself, determinative.

- Nature of the Shares and Financial Impact: The Court noted that the proper market value of the Company B shares was difficult to ascertain (suggesting they might be unlisted or thinly traded). Depending on the actual sale price received, the transaction could potentially have a significant impact on Company X's overall assets and its profit and loss situation.

- Non-Ordinary Course of Business: The sale of this substantial block of shares in Company B was characterized as not belonging to Company X's ordinary course of business activities.

- Strategic Importance and Inter-Company Relationship: This was a critical factor highlighted by the Supreme Court. The shares sold represented 7.56% of Company B's total issued stock. Perhaps more significantly, Company B, in turn, held a substantial 17.86% of Company X's issued stock, indicating a significant mutual shareholding relationship. Evidence also suggested that Company B had actively participated in a Company X shareholders' meeting on May 30, 1990 (after the disputed sale but before the lawsuit crystallized certain aspects of the relationship), even proposing a motion regarding director appointments. The Supreme Court reasoned that, given this interconnectedness, the disposition of Company X's shares in Company B could materially affect the relationship between the two companies and was therefore of "considerable importance" to Company X, beyond just its direct financial value.

- Company's Past Practice: There was evidence suggesting that Company X's board of directors had, in the past, made decisions regarding the disposition of even smaller holdings of shares in other companies. This indicated an internal company practice of treating such share sales as matters for board-level deliberation.

Considering all these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court could not properly determine that the sale of the Company B shares was not a disposition of important property based solely on the limited reasons it had cited (primarily that the shares were not indispensable to operations and that proceeds were received). A more thorough examination, taking into account all the elements of the comprehensive test, was required.

Analysis and Implications: Defining "Important Property"

This 1994 Supreme Court judgment was a landmark because it was the first time Japan's highest court explicitly laid out a multi-factor test for interpreting what constitutes a "disposition of important property" requiring board approval.

- Background of the Board Approval Rule:

The requirement for board approval for the disposition of important property (now Article 362, Paragraph 4, Item 1 of the Companies Act) was part of broader reforms in Japanese company law (specifically, the 1981 revision of the Commercial Code) aimed at strengthening the supervisory role of the board of directors over representative directors and clarifying the board's exclusive decision-making powers on critical matters. This was intended to prevent representative directors from unilaterally making major decisions that could significantly affect the company. - The Multi-Factor Test in Detail:

The Supreme Court's test emphasizes a holistic rather than a purely mechanical approach:- Value of the Property: While the absolute monetary value is a consideration, it's rarely decisive on its own, as "important" is relative to the company's scale.

- Proportion to Total Assets: This is a common metric. Some practitioners and commentators, drawing from this judgment, have discussed informal benchmarks like 1% of total assets as a potential (but not definitive) indicator. However, the Supreme Court itself showed that a figure like 1.6% was not dispositive and that the quality of this ratio (e.g., whether based on book values or fluctuating market values for both the asset and total assets) can make it an ambiguous measure if used in isolation.

- Purpose of Holding the Property: This requires looking beyond the asset's direct financial return. The Supreme Court specifically rejected the High Court's narrow focus on the fact that Company X merely received dividends from the Company B shares. The strategic value of an asset – such as its role in an inter-company relationship, its potential for influencing another entity, or its connection to the company's core business – can make it "important" even if it doesn't generate substantial direct income or isn't used daily in operations. The mutual shareholding between Company X and Company B, and Company B's active participation in Company X's governance, were key strategic elements here.

- Nature and Manner of the Disposition: This involves considering how the asset is being disposed of (e.g., sale, gift, pledge) and under what terms (e.g., whether for adequate consideration). A disposition for no consideration or for a grossly inadequate price would naturally heighten scrutiny.

- Company's Past Practices: If a company has a consistent history of bringing similar types of asset dispositions before the board for approval, this can indicate an internal understanding within that company that such matters are indeed "important." However, legal commentators caution that this factor should be seen as subsidiary. A company's past illegal or improper practice of not seeking board approval for what should have been considered important dispositions cannot legitimize future similar omissions. As the Supreme Court's own judicial research officer noted in a commentary on this case, an unlawful past practice doesn't make that practice lawful for that specific company. Nevertheless, if a company has formal internal guidelines (e.g., stipulating that asset dispositions above a certain value require board approval), adherence to or deviation from such guidelines could be a relevant consideration.

- Non-Ordinary Course of Business: The Supreme Court also pointed out that the sale of the Company B shares was not part of Company X's ordinary business activities. Some scholars place significant emphasis on this criterion: transactions that are unusual or outside the company's day-to-day operations are more likely to be deemed "important."

- The Challenge of "Comprehensive Consideration":

While the Supreme Court provided a list of factors, it did not specify how these factors should be weighted or how the "comprehensive consideration" should precisely be undertaken. This leaves room for judicial discretion in future cases. Some legal academics have debated whether quantitative factors like value and proportion to total assets should act as an initial screen (with qualitative factors becoming more decisive if a certain financial threshold is not met), or if all factors should be weighed more holistically from the outset. This Supreme Court judgment appears to lean towards a holistic assessment but clearly gave significant weight to the qualitative and strategic aspects of the shareholding in Company B. - Consequences of Lacking Required Board Approval:

Although this judgment focused on whether board approval was needed (i.e., if the property was "important"), it's crucial to understand the consequences if such required approval is absent. The prevailing Supreme Court view on actions taken by a representative director without necessary board approval (established in a 1965 case often cited alongside this one) is that such actions are not automatically or absolutely void. Instead, a theory of "relative invalidity" applies: the company can only assert the invalidity of the transaction against a third party if that third party knew about the lack of board approval or was negligent in not knowing about it. This standard has itself been criticized by some as being potentially too harsh on third parties, as proving their knowledge or negligence can be difficult for the company. There's an ongoing legal discussion about the appropriate balance between defining "important property" (and thus the scope of mandatory board approval) and the rules governing the validity of transactions made in breach of that requirement. A broader definition of "important" might be balanced by a rule that more readily protects innocent third parties, and vice-versa.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's January 20, 1994, judgment is a cornerstone in Japanese corporate law for defining what constitutes the "disposition of important property" requiring a board of directors' resolution. By establishing a multi-factor, comprehensive test, the Court moved beyond simplistic quantitative measures like asset ratios. It emphasized that factors such as the strategic purpose for which an asset is held, the nature of the transaction, its deviation from the ordinary course of business, and the company's own past practices must all be weighed alongside purely financial considerations. This holistic approach ensures that decisions with a potentially significant impact on a company's overall health, strategy, and inter-corporate relationships are subjected to the collective deliberation and judgment of the board, rather than being left to the sole discretion of the representative director. The ruling underscores the board's critical oversight role in safeguarding substantial corporate assets.