What is Tax Evasion Fraud? Japanese Supreme Court on "Deceit or Other Wrongful Acts"

Date of Judgment: November 8, 1967

Case Name: Commodity Tax Act Violation Case (昭和40年(あ)第65号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

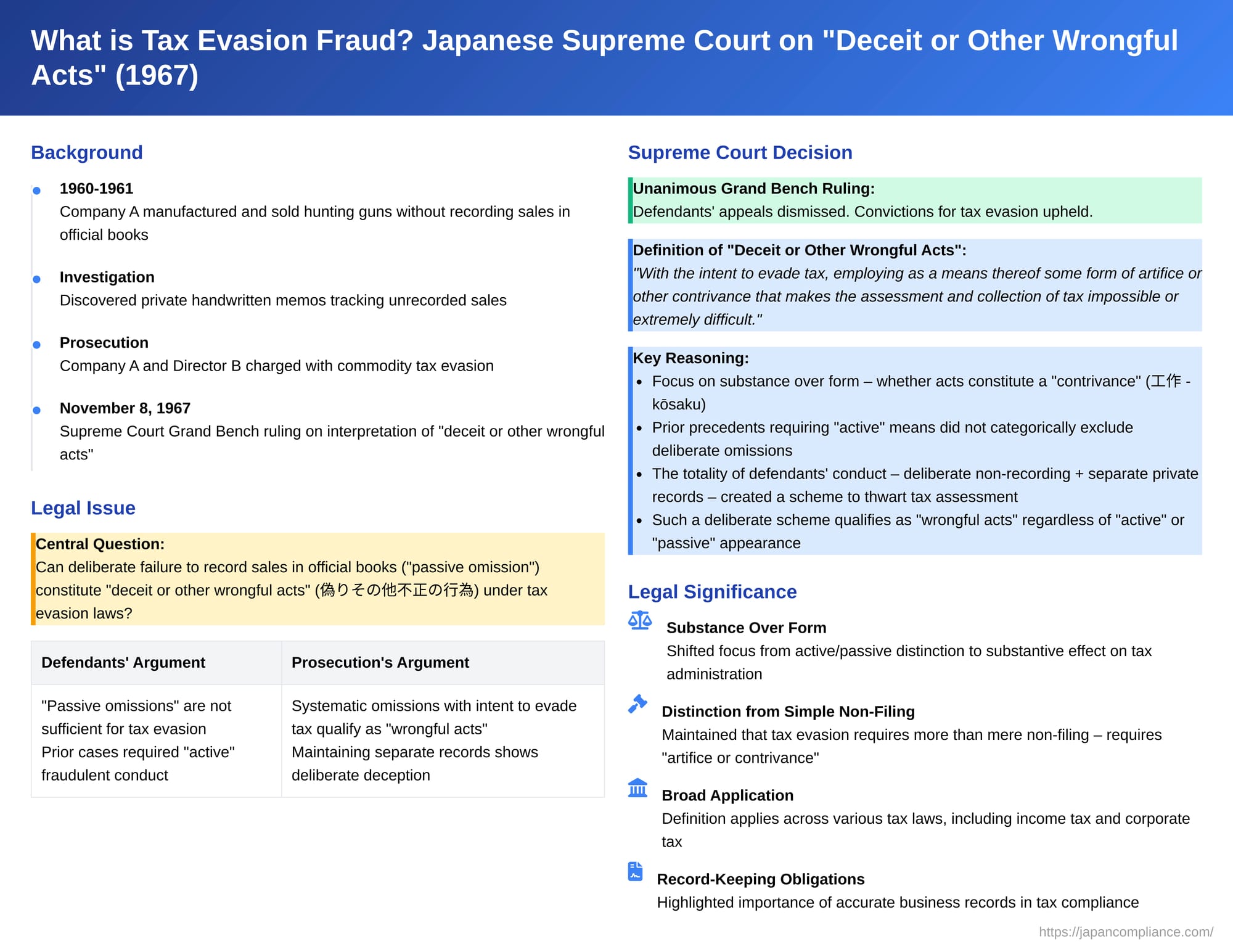

In a significant Grand Bench judgment on November 8, 1967, the Supreme Court of Japan provided a crucial interpretation of the phrase "deceit or other wrongful acts" (偽りその他不正の行為 - itsuwari sonota fusei no kōi), a key element in defining the crime of tax evasion under Japanese tax laws. The case involved a company and its director prosecuted for evading the old Commodity Tax by systematically failing to record sales in official books. The defendants argued their actions were mere "passive omissions" and did not meet the standard of "active" fraudulent conduct required by prior case law. The Supreme Court, however, rejected this narrow interpretation, focusing instead on whether the conduct, regardless of its active or passive appearance, constituted a deliberate scheme to make tax assessment and collection impossible or extremely difficult.

The Hidden Gun Sales: A Case of Alleged Omission

The defendants in this criminal case were Company A, a limited liability company engaged in the manufacturing and sale of hunting guns, and B, its director who was responsible for the company's overall operations. The prosecution alleged that between October 1960 and October 1961, on 13 separate occasions, B, acting on behalf of Company A and with the clear intention of evading commodity tax, engaged in the following conduct:

- Manufactured hunting guns and sold them to various outlets, including C Gun Shop.

- Deliberately did not record these taxable sales in the official company books that were required to be maintained and made available for inspection by tax officials.

- Instead of using the official books, B kept separate, private handwritten memos of these sales.

- Made false statements or declarations to tax officials concerning these transactions.

- Consistently failed to submit the required monthly tax base declarations for commodity tax to the competent tax office.

Through these actions, B and Company A were accused of evading commodity tax due each month. The first instance court found them guilty of tax evasion under the old Commodity Tax Act (the version prior to its 1962 amendment). The appellate court (Tokyo High Court) upheld these convictions. It reasoned that even "passive wrongful acts," such as deliberately omitting sales from official records to obscure the true state of business affairs, could, when done with the intent to evade tax, constitute the "deceit or other wrongful acts" necessary for the crime of tax evasion.

The defendants appealed to the Supreme Court, specifically to the Grand Bench, which handles cases of major legal or constitutional importance. Their primary argument was that their conduct—particularly the failure to record sales in the official books—amounted to mere "passive omissions" (shōkyokuteki na fusakui). They cited several prior Supreme Court precedents (a Showa 24 (1949) judgment concerning income tax, a Showa 38 (1963) judgment also on income tax, and another Showa 38 (1963) judgment specifically on commodity tax). These precedents, they argued, established that the crime of tax evasion requires "active" (sekkyokuteki ni) fraudulent means, going beyond mere "simple non-filing" (tanjun fushinkoku). They contended that the High Court's decision, by treating their ostensibly passive non-recording as sufficient for a conviction, contradicted these established Supreme Court precedents.

The Legal Crux: Defining "Deceit or Other Wrongful Acts" for Tax Evasion

The core legal issue before the Grand Bench was the precise interpretation of the phrase "deceit or other wrongful acts," which is a constituent element of the crime of tax evasion (逋脱罪 - hodatsuzai) under various Japanese tax statutes. The key question was whether a deliberate and systematic pattern of omissions, such as intentionally not recording taxable transactions in official books while maintaining separate private records, if done with the intent to evade tax and with the effect of making tax assessment extremely difficult, could qualify as such "wrongful acts." This was particularly pertinent given the defendants' reliance on prior case law that seemed to emphasize the need for "active" fraudulent conduct.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Clarification

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench unanimously dismissed the defendants' appeal, thereby upholding their convictions for commodity tax evasion. In doing so, the Court provided a definitive interpretation of "deceit or other wrongful acts."

- The Definition of "Deceit or Other Wrongful Acts":

The Supreme Court defined the phrase as meaning: "with the intent to evade tax, employing as a means thereof some form of artifice or other contrivance (なんらかの偽計その他の工作 - nanraka no gikei sonota no kōsaku) that makes the assessment and collection of tax impossible or extremely difficult." - Reinterpreting "Active" Conduct from Prior Precedents:

The Court addressed the defendants' reliance on prior rulings that required "active" fraudulent means beyond simple non-filing. It clarified that those precedents, when stating that "active" measures were necessary, meant that in addition to merely not filing a return, there must be "some form of artifice or other contrivance" as defined above. The requirement for an "active" act was not intended to categorically exclude deliberate omissions if those omissions were part of a larger scheme designed to thwart tax assessment and collection. The essence was the presence of a deceptive "contrivance" or "work" (kōsaku), not strictly whether it involved a commission or an omission in isolation. - Defendants' Conduct Constituted a "Contrivance":

Applying this definition to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had not simply equated mere non-recording in official books with a wrongful act. Instead, the High Court's decision was based on a totality of circumstances:- Defendant B, with the specific intent to evade commodity tax, deliberately refrained from recording the taxable sales of hunting guns in the official company books, which were subject to inspection by tax officials.

- While doing so, B maintained separate, private handwritten memos of these unrecorded sales, indicating a conscious effort to track them outside the official accounting system.

- No other official company records accurately reflected these sales, and related documents like delivery slips were also managed in such a way that the true facts of these transactions were almost entirely obscured.

The Supreme Court concluded that these actions, taken together, clearly demonstrated a deliberate "contrivance" or scheme specifically designed to make the assessment and collection of commodity tax by the authorities extremely difficult. This conduct, therefore, squarely fell within the definition of "deceit or other wrongful acts" and constituted the "active wrongful means" contemplated by the prior precedents. The High Court's judgment, in finding the defendants guilty on this basis, did not contradict existing Supreme Court case law.

Analysis and Significance

This 1967 Grand Bench decision is a landmark ruling in the interpretation of Japanese tax evasion laws:

- Focus on Substantive Effect, Not Just the Form of Conduct: The judgment was pivotal in shifting the legal emphasis from a potentially rigid distinction between "active" commissions and "passive" omissions to a more substantive assessment of the taxpayer's conduct and its effect on the tax administration's ability to assess and collect taxes. Deliberate acts, including omissions that are part of a calculated scheme to deceive or obstruct, can constitute "deceit or other wrongful acts" if they are intended to make tax assessment impossible or extremely difficult.

- Distinction from "Simple Non-Filing" Maintained: Importantly, the decision, by affirming the reasoning of prior cases, still maintained the crucial distinction between the serious crime of tax evasion (which requires "deceit or other wrongful acts") and the lesser offense of "simple non-filing" (tanjun fushinkoku). Merely failing to file a tax return, even with an intent to evade, does not, by itself, satisfy the requirement for "deceit or other wrongful acts." The crime of tax evasion necessitates an additional element of positive "artifice or other contrivance" designed to thwart the tax system.

- Broad Applicability of the Definition: Although this particular case dealt with the old Commodity Tax Act (which, at the time, operated on an official assessment basis rather than a self-assessment system for some aspects), the Supreme Court's definition of "deceit or other wrongful acts" has been regarded by legal commentators as having broader applicability. Its principles are considered influential for interpreting similar provisions in other tax laws, including those governing income tax and corporate tax, which are primarily based on self-assessment. The core concept of conduct intended to make assessment and collection impossible or extremely difficult through some form of artifice is generally transferable across different tax types.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench decision of November 8, 1967, provided a crucial and enduring clarification of what constitutes "deceit or other wrongful acts" for the purpose of establishing the crime of tax evasion in Japan. By focusing on the intent to evade and the employment of any "artifice or other contrivance" that makes tax assessment and collection impossible or extremely difficult, the Court moved beyond a simplistic active/passive distinction. This interpretation emphasizes the substance and effect of a taxpayer's conduct, ensuring that deliberate and systematic schemes to hide income or transactions from tax authorities, even if involving omissions in official records, can be prosecuted as serious tax evasion, provided they go beyond mere simple non-filing and involve a clear element of deceptive machination.