What is a "Secret"? Japan's Supreme Court Defines Confidentiality for Public Officials

Decision Date: December 19, 1977

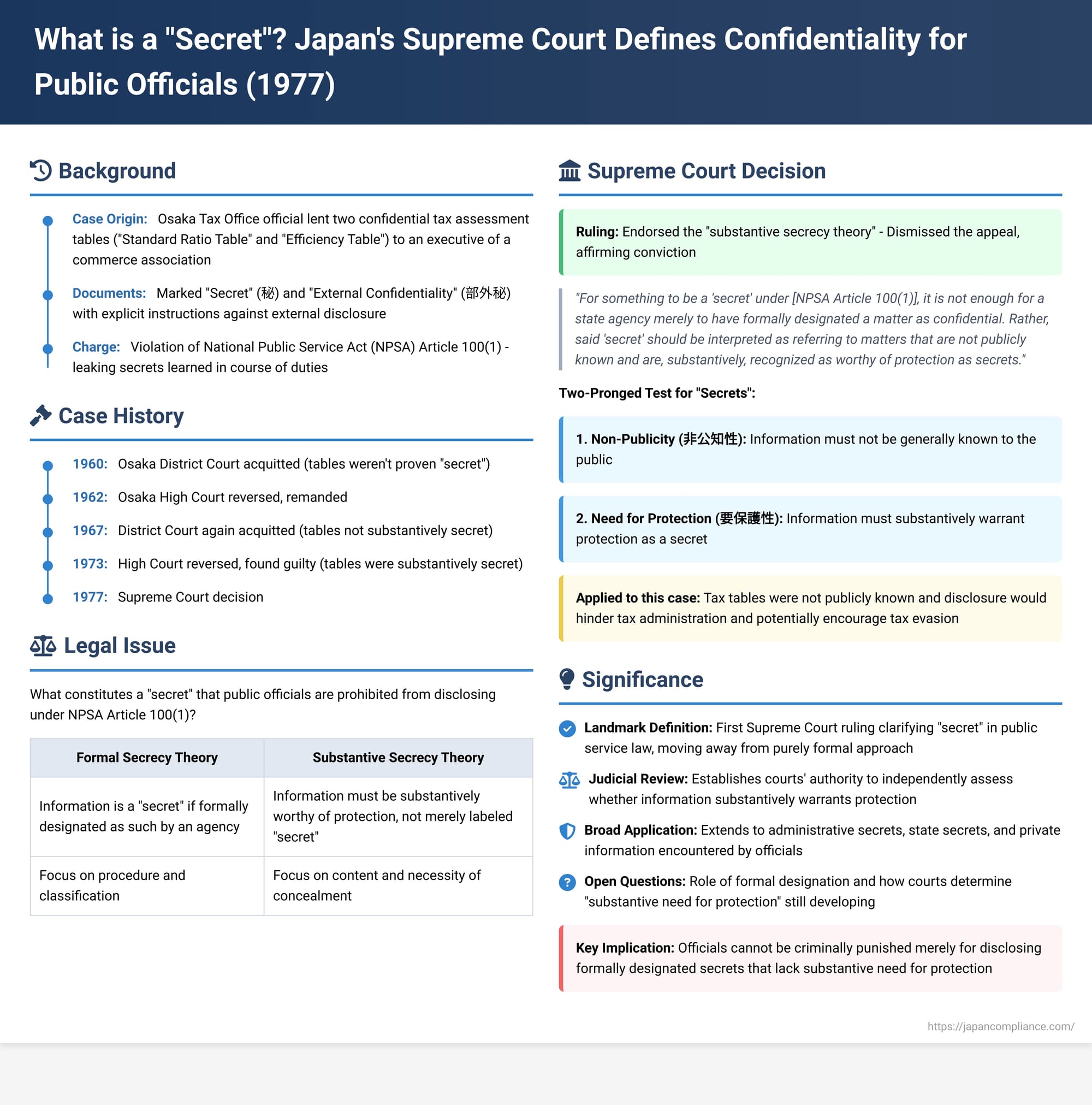

The duty of confidentiality is a fundamental obligation for public officials worldwide, designed to protect sensitive government information and ensure the proper functioning of the state. In Japan, the National Public Service Act (NPSA) imposes this duty, and breaches can lead to criminal penalties. However, what exactly constitutes a "secret" that an official is barred from disclosing? A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on December 19, 1977 (Showa 48 (A) No. 2716), provided a crucial definition, moving away from a purely formal understanding of secrecy to one grounded in substantive considerations. This case has since become a cornerstone in interpreting the scope of a public official's duty of confidentiality.

The Case of the Leaked Tax Tables

The defendant in this case was an official working in the direct tax section of the Sakai Tax Office, under the jurisdiction of the Osaka Regional Taxation Bureau. His responsibilities included income tax assessment. The official lent two documents—a "Standard Ratio Table" (Eigyōshogyōtō Shotoku Hyōjunritsuhyō) and an "Efficiency Table" (Shotoku Gyōshumokubetsu Kōritsuhyō) (collectively, "the two tables")—to an individual identified as A, an executive of the Osaka Federation of Commerce and Industry Associations.

These two tables were not ordinary documents. They had been created by the Osaka Regional Taxation Bureau as internal materials for tax assessment purposes and were distributed to various tax offices under its purview. Critically, they were designated as documents requiring external secrecy. The Standard Ratio Table's cover was printed with the word "Secret" (秘), and the Efficiency Table's cover with "External Confidentiality" (部外秘). Furthermore, they were distributed with a directive explicitly cautioning officials to "strictly ensure that they are not leaked externally."

The official was subsequently prosecuted for leaking secrets in violation of Article 100, paragraph 1 of the National Public Service Act, an offense punishable under Article 109, item 12 of the same Act. Article 100(1) states: "An official shall not leak any secret which may have come to his/her knowledge in the course of his/her duties. This shall also apply after he/she has retired from his/her position."

The case had a lengthy and complex journey through the lower courts before reaching the Supreme Court.

- The initial trial at the Osaka District Court (Showa 35, or 1960) resulted in an acquittal. The court adopted what is known as the "substantive secrecy theory" (jisshitsubi setsu), which posits that for information to be a legally punishable "secret," it must not only be formally designated as such but must also be substantively worthy of protection. The court found it could not determine the secrecy of the tables because the versions submitted as evidence by the prosecution were largely blacked out.

- On appeal, the Osaka High Court (Showa 37, or 1962) overturned this acquittal and remanded the case, stating that the secrecy of the tables could be determined even without the specific figures being visible.

- The second trial at the Osaka District Court (Showa 42, or 1967) again resulted in an acquittal. This court also applied the substantive secrecy theory and concluded that: (1) the two tables were effectively applied as rules or standards for determining taxable income and tax amounts; (2) concealing such assessment standards from the public was impermissible in light of the principle of "taxation by law" (sozei hōritsu shugi), which generally requires tax laws to be clear and public; and (3) disclosing the tables would not cause significant hindrance to tax administration. Therefore, the court denied the substantive secrecy of the tables' contents.

- However, the second appeal at the Osaka High Court (Showa 48, or 1973) reversed this second acquittal and found the defendant guilty. This appellate court also adopted the substantive secrecy theory but reached a different conclusion on the facts. It argued that: (1) the principle of taxation by law does not extend to guaranteeing taxpayers predictability in the fact-finding aspects of tax assessment, so there was no inherent need to publish the tables; (2) disclosing the tables would, in fact, cause harm to tax administration, thus necessitating their concealment; and (3) even if parts of the tables' contents were known to some taxpayers, the tables as a whole were not in a state of being publicly known.

The defendant appealed this guilty verdict to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Definition (December 19, 1977)

The Supreme Court dismissed the defendant's appeal, finding no valid grounds for it under the Code of Criminal Procedure. However, the Court then proceeded to rule ex officio (by its own authority, without it being a specific ground of appeal raised by the defendant) on the crucial legal question of what constitutes a "secret" under the National Public Service Act. This ex officio portion of the decision became the landmark ruling.

The Supreme Court declared:

"Considering the wording and purpose of Article 100, paragraph 1 of the National Public Service Act, for something to be a 'secret' under that provision, it is not enough for a state agency merely to have formally designated a matter as confidential. Rather, said 'secret' should be interpreted as referring to matters that are not publicly known and are, substantively, recognized as worthy of protection as secrets."

Applying this definition to the facts of the case, as determined by the High Court, the Supreme Court found:

"The 'Standard Ratio Table for Business and Other Incomes' and the 'Efficiency Table by Income and Business Category' were both, at the time of the incident, not yet generally known. Disclosing them would hinder the sound development of the self-assessment tax system centered on blue returns and could induce tax evasion, thus causing harm to tax administration, and therefore should be concealed from the public."

The Supreme Court thus affirmed the High Court's judgment that these tables constituted "secrets" within the meaning of NPSA Article 100, paragraph 1.

Unpacking "Substantive Secrecy"

This decision was highly significant because it was the first time the Supreme Court clearly endorsed the "substantive secrecy theory" over the "formal secrecy theory" (keishikibi setsu).

- The formal secrecy theory would hold that any information officially designated as secret by a state agency automatically qualifies as a "secret" for the purpose of the NPSA's confidentiality provisions.

- The substantive secrecy theory, adopted by the Court, requires a two-pronged test: the information must be (1) non-public and (2) substantively deserving of protection.

Legal commentary suggests several reasons why the Supreme Court might have favored the substantive approach, even though the decision itself only vaguely refers to "the wording and purpose" of the Act:

- Proportionality of Punishment: Leaking a "secret" under NPSA Article 100(1) carries criminal penalties (imprisonment or a fine). This is more severe than disciplinary action for a mere breach of a work order (e.g., an order to keep certain information confidential under NPSA Article 98(1), punishable under Article 82). Therefore, a "secret" subject to criminal sanctions should represent a more serious breach, involving information genuinely warranting such heightened protection.

- Avoiding Unjust Outcomes: The formal secrecy theory could lead to unjust results. For example, if information was once formally designated secret but subsequently lost all substantive need for protection (e.g., it became outdated or widely known through other means), an official leaking it could still be punished under a strict formal theory simply because the designation remained on the books. The substantive theory avoids this by allowing courts to assess the actual need for secrecy at the relevant time.

The Supreme Court's definition incorporates two key elements common to general definitions of "secret": non-publicity and the need for protection.

Key Elements of a "Secret" Further Examined

Non-Publicity (Hikōchisei)

The information must not be generally or publicly known. The second appellate court in this case had found that the tax tables were not publicly known, even if some parts might have been known to a limited number of taxpayers. This assessment—that partial or limited knowledge does not necessarily equate to public knowledge—is generally considered a valid interpretation, and the Supreme Court appeared to endorse it.

Need for Protection (Yōhogosei)

Beyond not being public, the information must be such that there is a legitimate interest in keeping it confidential. This "need for protection" is assessed substantively. In the present case, the Supreme Court, relying on the High Court's findings, determined that the disclosure of the tax tables would cause harm to tax administration by undermining the self-assessment system and potentially encouraging tax evasion. Some legal critiques have questioned the extent of this asserted harm in this specific instance, but the principle of requiring a substantive need for protection was clearly established.

Is Formal "Secret" Designation Necessary?

An important nuance within the substantive secrecy theory concerns whether a formal designation of secrecy by an administrative agency is also a prerequisite. Some interpretations, sometimes called composite or intermediate theories, suggest it is. Indeed, some lower court decisions prior to this Supreme Court ruling seemed to lean this way.

The Supreme Court's phrasing in this 1977 decision—"merely to have formally designated... is not enough"—could be read as implying that formal designation is a necessary, though not sufficient, condition. However, legal commentary suggests this was likely not a consciously articulated requirement by the Court in this specific ruling.

A later Supreme Court decision in a different case (the Foreign Ministry secret leak case, Showa 53.5.31) defined "secret" without mentioning formal designation as a necessary component. This has led some to believe that formal designation is not required by the Supreme Court, although the point was not a central issue in that particular case, so its precedential value on this specific aspect might be limited.

There are academic arguments supporting the requirement of formal designation, such as it acting as a safeguard against the arbitrary or overly broad application of secrecy laws by public officials and ensuring clarity and due process for employees who need to know what information they cannot disclose.

However, there are strong counterarguments. Many types of highly sensitive information held by government agencies, such as records of ongoing criminal investigations, may be substantively secret but not always carry a formal "secret" stamp. Moreover, not all secrets known to public officials are in documented form. Requiring formal designation for documented secrets but not for undocumented ones would create an inconsistency: information deserving protection would lose that status merely by being written down without a formal stamp, or gain it only if stamped. While it's true that information which the secret-holder (the state, in this context) has no intention of keeping secret should not be criminally protected, this intention does not necessarily need to be manifested through a formal designation for the purposes of NPSA Article 100(1). (This is distinct from specific laws like the Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets, which do mandate special designation procedures). Illustrating this, a Kyoto District Court case found that the date of an unannounced inspection by city officials under the Waste Management Act constituted a "secret" under the Local Public Service Act, even without a formal designation, because its premature disclosure would hinder administrative execution.

How is "Substantive Secrecy" Judged by Courts?

If the substantive secrecy theory is adopted, a critical practical question arises: how do courts determine this "substantive need for protection"? Some proponents of the substantive theory argue that a formal designation by an agency should at least create a presumption that the information is substantively secret, which could then be rebutted. A 1969 Tokyo High Court decision, for example, stated that an agency's determination of secrecy should be respected and, unless officially declassified, the necessity and protectability of the secret are presumed by its designation. Such a stance, if adopted, could make the substantive theory operate very similarly to the formal theory in practice, leading some to criticize it as a "formalistic substantive secrecy theory."

The 1977 Supreme Court decision did not directly address the issue of such a presumption, as it relied on the lower appellate court's factual findings regarding the harm of disclosure. However, the subsequent Supreme Court ruling in the Foreign Ministry secret leak case explicitly stated that the determination of whether information constitutes a "secret" is ultimately a matter for judicial judgment. This suggests that the Supreme Court does not endorse a strong presumption arising from formal designation alone, favoring a more independent judicial assessment.

Scope and Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's 1977 decision has become a foundational precedent in Japanese public service law. Its adoption of the "substantive secrecy theory" was later confirmed in the Foreign Ministry secret leak case. This interpretation naturally extends to similar confidentiality provisions in other laws governing public officials, such as the Local Public Service Act and the Self-Defense Forces Act.

It's important to note that the concept of "secrets" known to officials in the course of their duties is broad. While this particular case dealt with "administrative secrets" (internal documents related to tax administration), the principles laid out also apply to "state secrets" in a narrower sense (e.g., national security information) and, significantly, to "private secrets" that officials might encounter. The latter category includes proprietary business information or personal privacy details of citizens. When assessing the "need for protection" for such private secrets, different considerations come into play compared to state or administrative secrets, where the public's right to know and the principle of open government might weigh against secrecy. For instance, a 2013 Nagoya High Court decision held that car users' names and addresses recorded in vehicle registration files constitute private information and are, substantively, worthy of protection as "secrets" under NPSA Article 100(1), regardless of whether they qualify as state secrets.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 19, 1977, decision was a pivotal moment in defining the legal boundaries of official secrecy in Japan. By firmly establishing the "substantive secrecy theory," the Court mandated that for a public official to be criminally liable for leaking information, that information must not only be non-public but must also be demonstrably worthy of protection as a secret. This moves beyond mere formal classifications by government agencies, empowering the judiciary to make the ultimate determination based on the substance of the information and the potential harm from its disclosure. While leaving some nuances open for future clarification, such as the precise role of formal designations, the ruling underscored that the duty of confidentiality, while critical, must be grounded in a genuine and judicially verifiable need to protect legitimate state or private interests.