Wearing Union Insignia at Work: The Taisei Kanko (Hotel Okura) Supreme Court Decision

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of April 13, 1982 (Case No. 1977 (Gyo Tsu) No. 122: Revocation of Unfair Labor Practice Relief Order)

Appellant (Labor Relations Commission): Y (Tokyo Local Labor Relations Commission)

Appellee (Company): X Company

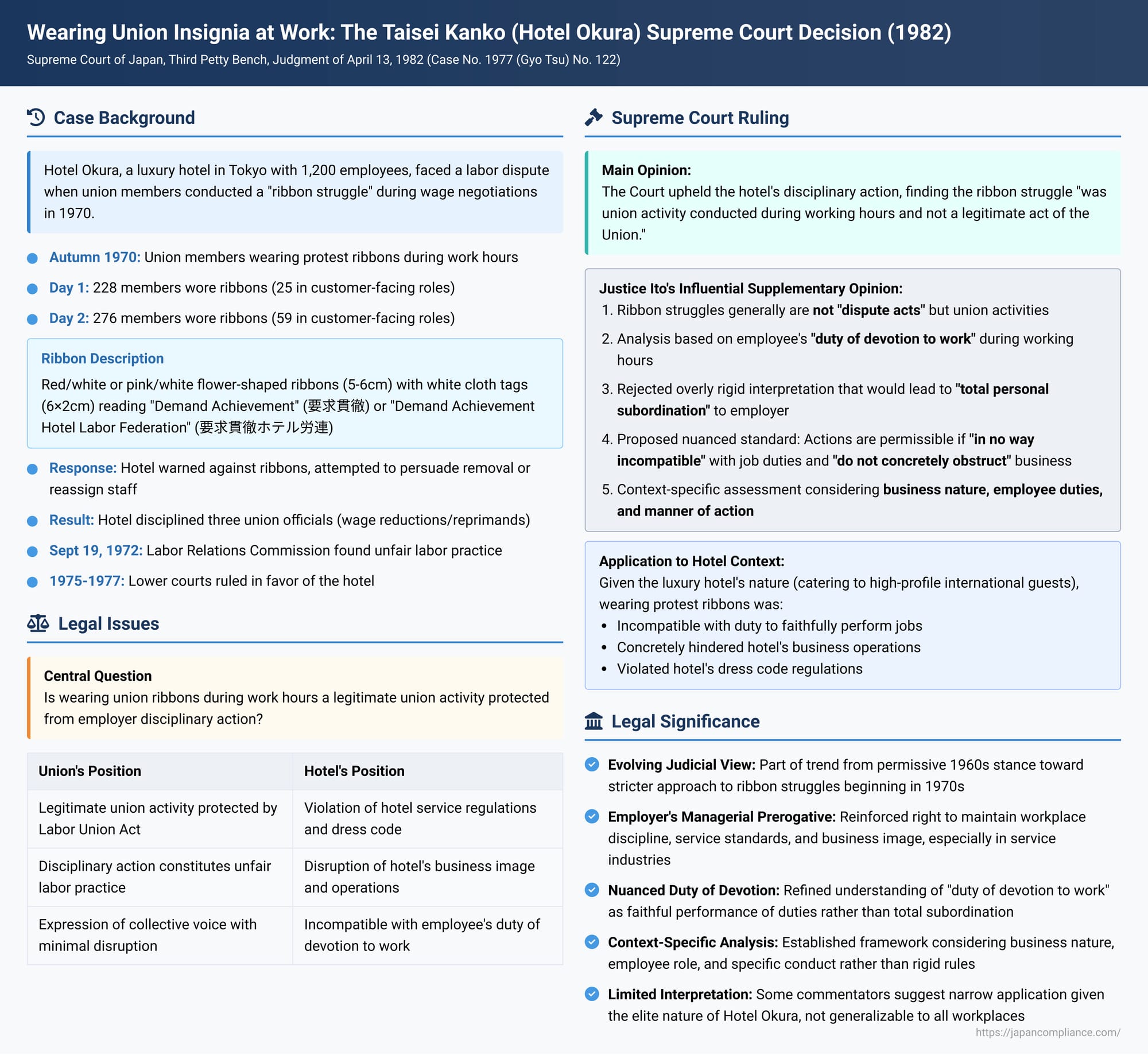

The right of union members to engage in union activities is a fundamental aspect of labor law. However, when these activities take place during working hours and within the employer's premises, they can intersect with the employer's managerial rights and the employee's contractual obligations. A common form of such activity is the "ribbon struggle" (ribon tōsō), where employees wear ribbons, badges, or other insignia displaying union demands or affiliation. The Japanese Supreme Court's judgment on April 13, 1982, in the Taisei Kanko case (often referred to as the Hotel Okura case, after the name of the hotel operated by the company), is a significant decision that addressed the legitimacy of such actions, particularly within the context of a customer-facing service industry.

The Seeds of Conflict: Facts of the Case

The dispute involved X Company, which operated a prominent hotel in Tokyo (Hotel O) and employed approximately 1200 individuals. A Union, composed of X Company's employees and affiliated with the B Labor Union Federation, was engaged in collective bargaining with X Company over wage increases in the autumn of 1970.

Dissatisfied with the company's offers, A Union, after securing a strike vote, notified X Company that it would conduct a "ribbon struggle" if a more favorable response was not forthcoming. Despite a further response from X Company, A Union remained unsatisfied and instructed its members to proceed with the ribbon struggle for approximately two days.

During this period:

- On the first day, 228 union members (out of approximately 950-989 employees on duty) participated, with about 25 of these being in customer-facing roles.

- On the second day, 276 members participated, with about 59 in customer-facing roles.

- The ribbons worn were either red and white flower-shaped (approx. 6cm in diameter) or pink and white flower-shaped (approx. 5cm in diameter). Attached to these ribbons were white cloth tags (approx. 6cm long and 2cm wide) bearing inscriptions such as "Demand Achievement" (要求貫徹) or "Demand Achievement Hotel Labor Federation" (要求貫徹ホテル労連). These were worn on the upper part of their uniforms, below their name tags.

Upon being notified of the planned ribbon struggle, X Company warned A Union to prohibit the wearing of ribbons during work hours. The company also attempted to persuade employees wearing the ribbons to remove them or reassigned some to positions not visible to guests. However, some employees disregarded these instructions and continued to wear the ribbons while interacting with hotel guests.

As a result, X Company took disciplinary action (wage reductions or formal reprimands) against three principal officials of A Union, C and others, who had directed the ribbon struggle. The company cited violations of its work rules, specifically the service regulations regarding employee conduct and appearance.

A Union, B Federation, and the disciplined officials (C and others) filed a complaint with Y (the Tokyo Local Labor Relations Commission), asserting that these disciplinary measures constituted an unfair labor practice, specifically disadvantageous treatment due to legitimate union activities (as prohibited by Article 7, Item 1 of the Labor Union Act). The Labor Relations Commission agreed, finding the company's actions to be an unfair labor practice, and issued a relief order on September 19, 1972.

X Company then initiated administrative litigation to have the Labor Relations Commission's order revoked.

The Journey Through the Lower Courts

The Tokyo District Court (judgment of March 11, 1975) sided with X Company and revoked the Labor Relations Commission's order. The District Court opined that ribbon struggles generally possess a dual nature, being both union activity and a form of dispute act, and found them to be generally illegal in both aspects. It further stated that such actions take on a special dimension of illegality when conducted in the hotel industry.

Y (the Labor Relations Commission) appealed this decision, but the Tokyo High Court (judgment of August 9, 1977) upheld the District Court's ruling, making only minor additions and corrections to the original judgment. This led Y to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Main Finding

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, dismissed the appeal by the Labor Relations Commission. This effectively upheld the company's disciplinary actions by finding that the ribbon struggle was not a "legitimate act" of the union.

The main opinion of the Court was notably brief: "Under the facts lawfully established by the court below, the High Court's determination that the ribbon struggle in this case was union activity conducted during working hours and not a legitimate act of A Union can be affirmed as correct in its conclusion."

While concise, this main opinion aligned with a developing judicial trend that was becoming more critical of ribbon struggles.

Justice Masami Ito's Influential Supplementary Opinion – A Deeper Dive

More illuminating and subsequently more influential in legal discussions was the supplementary opinion penned by Justice Masami Ito. This opinion provided a more detailed rationale for the Court's conclusion and addressed the broader legal principles at stake.

1. Ribbon Struggles: Generally Not "Dispute Acts"

Justice Ito began by clarifying the nature of ribbon struggles. While acknowledging that defining "dispute acts" (sōgi kōi) precisely is difficult and context-dependent, he stated that they generally involve a work stoppage (including slowdowns or refusal of overtime) by the union to assert its demands. He opined that while some forms of ribbon display, depending on the nature of the business, could conceivably be equivalent to a work stoppage, ribbon struggles as a category are generally not dispute acts. Based on the facts of this particular case, he concluded it was not appropriate to treat this ribbon struggle as a dispute act.

2. Legitimacy as Union Activity During Work Hours: The "Duty of Devotion to Work"

The core of Justice Ito's analysis focused on whether the ribbon struggle could be considered a legitimate union activity (as distinct from a dispute act) when conducted during working hours.

- Traditional View and the Duty of Devotion to Work (Shokumu Sennen Gimu): He noted the general rule that union activities during working hours are not permitted unless the employer has given express or implied consent, or where such activities are allowed by established labor-management practice. This rule, he explained, is based on the employee's "duty of devotion to work"—an obligation arising from the labor contract for the employee to concentrate their energies exclusively on the performance of their duties during work hours.

- Critique of an Overly Strict Interpretation: Justice Ito cautioned against an overly rigid interpretation of this duty. He argued that if the duty of devotion to work were taken to mean that employees must dedicate all their physical and mental energy solely to their job duties, with no attention diverted to anything else during work hours, it would effectively lead to the "total personal subordination" of the employee to the employer during that time. He referenced a previous Supreme Court case (the M T T O case, 1977 ) which seemed to adopt such a strict stance regarding the wearing of political plaques by public sector employees, but he distinguished the present case involving private sector union activity.

- Justice Ito's Nuanced Interpretation: He proposed that the duty of devotion to work should be understood as an obligation for the employee to faithfully perform their duties as stipulated in the labor contract. Crucially, he stated: "Actions that are in no way incompatible with this duty and do not concretely obstruct the employer's business are not necessarily in breach of the duty of devotion to work."

- Context is Key: Whether a specific action breaches this duty is not an absolute determination but depends on a consideration of various factors, including "the nature and content of the employer's business and the employee's duties, and the manner of the action in question."

3. Application to the Hotel Context:

Applying this nuanced standard to the facts of the Taisei Kanko case, Justice Ito concluded that the ribbon struggle was not legitimate:

- He found that, given the nature of X Company's luxury hotel business (which catered to high-profile international guests), the act of employees wearing these particular ribbons during work hours was incompatible with their duty to faithfully perform their jobs.

- Furthermore, he determined that it did concretely hinder the hotel's business operations, likely due to the potential negative impact on the hotel's image, atmosphere, and guest experience.

- Therefore, even when viewed as a union activity (rather than a dispute act), the ribbon struggle in this specific context did not possess legitimacy.

- Justice Ito also briefly noted that, under the established facts, the ribbon struggle could be considered a violation of the hotel's dress code, further undermining its legitimacy.

Evolution of Judicial Views on Ribbon Struggles

The Taisei Kanko judgment, particularly Justice Ito's supplementary opinion, is best understood within the context of an evolving judicial approach to ribbon struggles in Japan.

- Early Views (Pre-1970s): Earlier court decisions, up until around the early 1970s, often found ribbon struggles to be legitimate union activities that did not necessarily violate workplace rules or the duty of devotion to work (e.g., the Z T N P O case, Kobe District Court; the S S B case, Sendai District Court).

- Shift Towards a Stricter Stance (1970s onwards): However, starting in the 1970s, judicial attitudes began to shift. A series of court rulings, including cases like the C N B cases (Nagoya High Court and District Court) and appellate decisions in cases like K S C (Sapporo High Court) and Z T N P O (Osaka High Court), started to place greater emphasis on the duty of devotion to work and the potential for ribbon struggles to disrupt workplace order and business operations. This led to an increasing tendency to find such activities illegitimate. The Supreme Court's own M T T O case (1977), concerning public sector employees and political messages, defined the duty of devotion very strictly as using all one's attention for work.

- Taisei Kanko's Place in This Trend: The Taisei Kanko decision is squarely within this trend of increasing judicial skepticism towards the legitimacy of ribbon struggles during work hours. This case was even more thorough in its negative assessment of ribbon struggles than previous rulings. This judicial direction continued in later years, influencing decisions on related issues such as the wearing of union badges in the workplace (e.g., the J T (S B) case, Supreme Court 1998).

Significance and Implications of the Taisei Kanko Judgment

- Reinforcement of Employer's Managerial Prerogative: The decision, particularly in a high-end service industry context, reinforces the employer's right to maintain workplace discipline, uphold service standards, and protect its business image and operations from what it perceives as disruptive activities.

- The Duty of Devotion to Work as a Key Standard: The case, especially Justice Ito's opinion, highlighted the "duty of devotion to work" as a central legal concept for evaluating the legitimacy of union activities conducted during working hours. While Ito's formulation aimed for a more nuanced, less "total subordination" view than some previous strict interpretations, its application in this specific hotel context still led to a finding against the union activity.

- Context-Specific Analysis Emphasized: Justice Ito's opinion advocated for a context-dependent analysis, taking into account the nature of the business, the employee's role, and the specific conduct. This approach, in theory, allows for flexibility. However, in practice, especially in service industries, it has often led to outcomes unfavorable to such union activities.

- Impact on Union Tactics: This ruling, as part of a broader judicial trend, likely had a chilling effect on the use of ribbon struggles and similar forms of workplace expression as common union tactics, especially in environments where customer perception and workplace aesthetics are deemed critical by employers.

- Limited Interpretation Suggested by Some Commentators: The ruling in Taisei Kanko, given the specific elite nature of the hotel involved (catering to "heads of state, royalty... and other top-class foreign guests" ), should perhaps be interpreted narrowly and not over-generalized to all workplaces. An overly broad application could unduly restrict legitimate forms of union expression in settings where the impact on business or customer experience is less direct or negligible.

Conclusion

The Taisei Kanko (Hotel Okura) Supreme Court judgment is a significant case in Japanese labor law that illustrates the delicate balance between the right to engage in union activities and the employer's need to manage its operations and maintain workplace standards. While the main opinion was brief, Justice Masami Ito's supplementary opinion provided a more detailed, albeit ultimately restrictive in this instance, framework for assessing the legitimacy of union activities during work hours based on the "duty of devotion to work." The decision underscores that in customer-facing service industries, particularly those emphasizing a specific image or ambiance, activities like ribbon struggles are likely to face high hurdles in being recognized as "legitimate" if they are perceived to interfere with business operations or the expected service environment.