Wartime Claims and Post-War Treaties: The Japanese Supreme Court's Decision

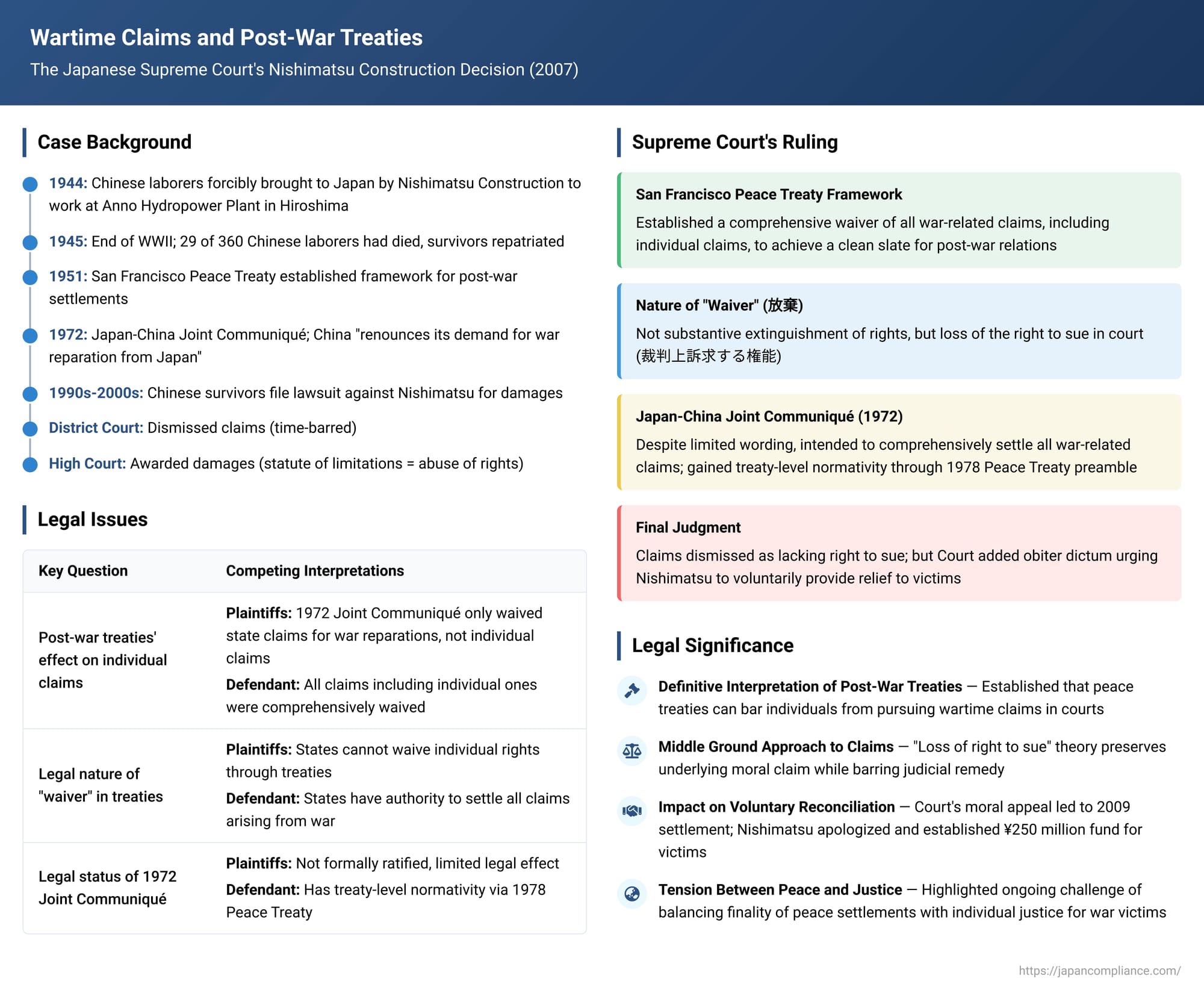

The legacy of World War II continues to cast long shadows, particularly concerning unresolved claims for wartime suffering. A significant ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 27, 2007, addressed the complex issue of individual compensation claims for forced labor against the backdrop of post-war peace treaties and diplomatic settlements. The case delved into the legal effect of these international agreements on the rights of individuals to seek redress in Japanese courts.

The Allegations: Forced Labor and a Quest for Justice

The plaintiffs in this case were Chinese nationals, or the successors of deceased victims, who asserted that during World War II, specifically in July 1944, they were forcibly brought from North China to Japan by Company N. They were allegedly compelled to work under harsh conditions at the Anno Hydropower Plant construction site in Hiroshima Prefecture until approximately the end of the war. Decades later, they filed a lawsuit against Company N, seeking damages. Their claims were founded on several legal bases: violations of international law (such as the prohibition of forced labor), tortious acts under Japanese civil law, and breach of contract, specifically alleging a failure of Company N's duty of care for their safety and well-being.

The historical context detailed in the court records painted a grim picture. During the war, Japan faced severe labor shortages, especially in critical sectors like mining, construction, and port services. To address this, the Japanese government implemented policies to mobilize labor, including the importation of workers from occupied territories. Following a cabinet decision in November 1942 titled "Regarding the Transfer of Chinese Laborers to Japan," and a subsequent decision in February 1944 to promote this transfer, a large-scale importation of Chinese laborers began. Company N, involved in constructing the Anno Hydropower Plant, applied for and received an allocation of these Chinese laborers to supplement its workforce.

The plaintiffs alleged that they (or their predecessors) were among the 360 Chinese laborers handed over to Company N in Qingdao in July 1944. They contended they were deceived or forcibly taken, transported to Japan under deplorable conditions (three died during the voyage), and housed in guarded facilities. They were forced into grueling labor, often in two shifts day and night, with grossly inadequate food, clothing, and medical attention. The judgment noted that of the initial 360 laborers at the Anno site, 29 (including the three who died en route) had perished by the time of their repatriation in November 1945. Some victims in this specific case suffered severe injuries like blindness, debilitating diseases, or died as a result of abuse or, in a tragic turn, were killed in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima while imprisoned following an internal dispute among the laborers. After the war, Company N reportedly received financial compensation from the Japanese government for losses incurred in relation to the Chinese laborers it had utilized. The plaintiffs asserted that they never consented to be brought to Japan or to work for Company N, nor did they enter into any employment contracts.

The Journey Through Lower Courts: A Divergence on Justice

The case wound its way through the Japanese judicial system with differing outcomes at each level.

Hiroshima District Court:

The court of first instance dismissed the plaintiffs' claims.

- Regarding claims based directly on international law (such as the Forced Labour Convention or the Hague Regulations), the court found that these treaties did not directly regulate legal relationships between private individuals or entities, and neither did relevant customary international law.

- While acknowledging that the forced labor constituted a tort under Japanese law, the court ruled that the right to claim damages had expired due to the statutory limitation period (a period of exclusion, joseki kikan).

- Similarly, for claims based on breach of contract (specifically, the duty of care for safety), the court found that while a breach occurred, the right to seek damages had been extinguished by the statute of limitations (shōmetsu jikō).

Hiroshima High Court:

The appellate court, the Hiroshima High Court, took a different view and overturned the District Court's decision, ruling in favor of the plaintiffs and awarding damages.

- The High Court agreed with the District Court's assessment regarding the expiration of claims based directly on international law and tort.

- However, concerning the breach of contract (duty of care), the High Court, while acknowledging that the claim would ordinarily be time-barred, found that Company N's invocation of the statute of limitations constituted an abuse of rights under the specific circumstances of the case and was therefore impermissible. These circumstances included the plaintiffs' factual inability to pursue claims earlier due to economic hardship and lack of information, factors partially attributable to Company N's actions, and Company N's conduct during later compensation negotiations which delayed the lawsuit.

- Crucially, the High Court rejected Company N's argument that the plaintiffs' claims had been waived by post-war diplomatic agreements, particularly Paragraph 5 of the 1972 Japan-China Joint Communiqué. The High Court interpreted this paragraph as a waiver by the People's Republic of China (PRC) government of its claims for "war reparations" only. It opined that such a communiqué could not, as a general principle, waive the inherent rights of individual Chinese nationals to seek damages from private Japanese entities for tortious acts.

Company N appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision: The Primacy of Post-War Settlements

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of April 27, 2007, reversed the Hiroshima High Court's ruling and ultimately dismissed the plaintiffs' claims. Its decision hinged on the interpretation and legal effect of post-war international agreements, particularly the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty (SFPT) and the 1972 Japan-China Joint Communiqué.

1. The San Francisco Peace Treaty Framework: A Comprehensive Settlement

The Supreme Court began by outlining the fundamental nature of the SFPT, which it described as the bedrock of Japan's post-war settlements.

- Comprehensive Waiver of Claims: The SFPT was premised on the mutual waiver of all claims arising from the war, including those held by individual nationals of the Allied Powers against Japan and its nationals, and vice-versa.

- Reparations and Asset Disposal: While acknowledging Japan's obligation to pay reparations for war damage and suffering, the SFPT also recognized that Japan's resources were insufficient for full compensation. It provided for Japan to make its overseas assets available to the Allied Powers for disposal (effectively as a form of reparation) and stipulated that specific arrangements for further reparations (including services) would be negotiated bilaterally between Japan and individual Allied nations.

- Purpose of the Framework: This comprehensive framework, including the waiver of claims, was intended to create a clean slate, preventing future disputes and endless litigation that could undermine the peace and stability sought by the treaty. The Court reasoned that allowing individual civil claims to be pursued after the conclusion of a peace treaty could impose unpredictable and excessive burdens on both states and their nationals, thereby hindering the objectives of achieving a lasting peace. This framework was intended to guide Japan's peace settlements not only with SFPT signatories but also with other nations.

- Meaning of "Waiver": The Court interpreted the term "waiver" (放棄 - hōki) of claims, as used in Article 14(b) of the SFPT (where Allied Powers waived their claims), not as the substantive extinguishment or annihilation of the underlying right itself. Instead, it meant the loss of the locus standi or the right to sue in court (裁判上訴求する権能を失わせる - saiban-jō sokyū suru kennō o ushinawaseru) based on that claim.

- State Authority over Individual Claims: The Court affirmed that a state, in concluding a peace treaty to end a war, has the authority, based on its sovereignty over its people (taijin shuken), to settle or dispose of claims, including those held by its individual nationals. This rejected the plaintiffs' argument that a state could not waive or limit the private rights of its citizens through an international agreement.

2. The 1952 Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty (Treaty of Taipei)

China was not a participant in the San Francisco Peace Conference due to the political division between the Republic of China (ROC) government in Taiwan and the newly established People's Republic of China (PRC) government in mainland China. Japan subsequently concluded a separate peace treaty with the ROC in Taipei in 1952.

- Article 11 of this treaty stipulated that issues arising as a result of the state of war between Japan and China would be resolved in accordance with the "relevant provisions" of the SFPT. The Supreme Court found that this naturally included the settlement of claims, encompassing those of individuals. Thus, in principle, all claims of China (as represented by the ROC) and its nationals arising from the Sino-Japanese War were deemed waived in a manner analogous to SFPT Article 14(b).

- However, the Court noted a critical qualification in an attached exchange of notes: the treaty's provisions would apply, with respect to the ROC, to "all the territories which are now, or which may hereafter be, under the control of its Government". Given that the ROC did not control mainland China, the Court acknowledged that this provision allows for a fully viable interpretation that the treaty's clauses on war reparations and claims settlement did not definitively apply to mainland China at the time, merely indicating a future possibility of application if the ROC regained control. Consequently, the Court stated it could not definitively assert that these provisions of the 1952 treaty automatically extended their legal effect to Chinese nationals residing in mainland China, like the plaintiffs in this case.

3. The 1972 Japan-China Joint Communiqué

In 1972, Japan normalized relations with the People's Republic of China, issuing the Japan-China Joint Communiqué. Paragraph 5 of this Communiqué is central to the case. It states: "The Government of the People's Republic of China declares that in the interest of the friendship between the Chinese and Japanese peoples, it renounces its demand for war reparation from Japan."

- Interpretation of Paragraph 5: The Supreme Court acknowledged that the literal wording of Paragraph 5—renouncing "its demand for war reparation"—does not explicitly state whether this waiver extends beyond state-to-state war reparations to include other claims, or whether it encompasses the waiver of claims held by individual Chinese nationals.

- Negotiation History and Mutual Understanding: However, the Court delved into the publicly known negotiation history of the 1972 normalization. It concluded that the PRC government clearly viewed Paragraph 5 not merely as a waiver of state reparations but as a foundational provision that settled all post-war issues with Japan, including the disposition of all types of claims arising from the war, in line with the comprehensive approach of the SFPT framework. The Japanese government, while maintaining its formal position that reparations and claims issues with "China" had been resolved by the 1952 Treaty of Taipei, understood that the 1972 Joint Communiqué achieved substantially the same comprehensive settlement with the PRC. The wording was carefully chosen to accommodate both sides' formal positions while achieving a de facto comprehensive resolution.

- Alignment with SFPT Framework: The Court reasoned that there was no indication that Japan and the PRC intended to deviate from the established SFPT framework for peace settlements, which included the waiver of individual claims[cite: 1, 2]. To leave individual claims unresolved would have risked future instability, contrary to the aims of normalizing relations and establishing lasting peace[cite: 2]. Therefore, the Court interpreted Paragraph 5 of the Joint Communiqué as clarifying the mutual waiver of all claims arising from the war, including those of individuals, by both sides[cite: 2].

- Legal Status and Normative Force of the Joint Communiqué: A key issue was the legal status of the Joint Communiqué, as it was not ratified by the Japanese Diet as a formal treaty. The Court addressed this by stating:

- The PRC undoubtedly recognized it as a foundational international legal norm establishing the basis for post-war relations[cite: 2].

- At the very least, it possessed normative force as a unilateral declaration by the PRC, binding upon it[cite: 2].

- Crucially, the 1978 Japan-China Treaty of Peace and Friendship, a formally ratified treaty, explicitly states in its preamble that the principles set forth in the 1972 Joint Communiqué should be strictly observed. The Supreme Court held that this provision in the 1978 Treaty effectively endowed the contents of Paragraph 5 of the 1972 Joint Communiqué with treaty-level legal normativity within Japan as well[cite: 2].

- Consequence for Individual Claims: Based on this interpretation, the Supreme Court concluded that claims by Chinese nationals against Japan or Japanese nationals/corporations, arising from wartime actions, lost their right to be pursued in Japanese courts due to the comprehensive waiver in Paragraph 5 of the Japan-China Joint Communiqué[cite: 2]. When such a waiver is invoked as a defense, the claims must be dismissed[cite: 2].

The Nature of "Waiver": Loss of Judicial Remedy

The Supreme Court's consistent interpretation of "waiver" in these post-war settlements, including the SFPT and the Japan-China Joint Communiqué, is critical. It signifies not the erasure or substantive extinguishment of the underlying claim or the moral right, but rather the forfeiture of the legal capacity to sue or seek judicial enforcement of that claim in the courts of the waiving state or the state against which claims are waived. This "right to relief, but no right to sue" theory means that while the legal pathway through courts is closed, the underlying facts of suffering or the moral dimension of the claim may remain[cite: 2].

The Court's Appeal for Voluntary Relief (Obiter Dictum)

Despite dismissing the plaintiffs' legal claims, the Supreme Court concluded its judgment with a significant obiter dictum (a non-binding remark). It noted that even within the SFPT framework, the waiver of the right to judicial remedy does not preclude voluntary or spontaneous actions by the debtor side to provide relief[cite: 2].

The Court then explicitly stated: "Considering the immense mental and physical suffering of the victims in this case, on the one hand, and on the other hand, the fact that the appellant [Company N] derived considerable benefits from compelling the Chinese laborers to work under the aforementioned conditions and, furthermore, received the aforementioned [post-war] monetary compensation, it is expected that the appellant, along with other concerned parties, will endeavor to provide relief for the damages suffered by the victims in this case." [cite: 2] This was a clear moral appeal from the nation's highest court for voluntary redress.

Significance and Postscript

The case decision had a profound impact on numerous similar lawsuits filed by former forced laborers and other war victims from Asian countries. It solidified the legal principle that comprehensive peace settlements, including the Japan-China Joint Communiqué, effectively barred individuals from pursuing wartime claims in Japanese courts.

The Court's adoption of the "loss of the right to sue" interpretation, as opposed to the substantive extinguishment of rights, occupies a middle ground between theories that only diplomatic protection was waived and theories that individual rights themselves were completely nullified[cite: 2]. The legal effect, however, is largely the same in terms of court-ordered compensation: neither the state nor private entities have a legal obligation to pay if the right to sue is waived[cite: 2].

Scholarly commentary has noted that the Supreme Court's reliance on the preamble of the 1978 Japan-China Treaty of Peace and Friendship to elevate Paragraph 5 of the 1972 Joint Communiqué to treaty-level normativity is a point of debate, with some questioning whether a preamble can carry such significant legal weight[cite: 2]. There have also been arguments suggesting that the original intent of the 1972 Communiqué, particularly from the Chinese perspective, may not have been to waive individual claims against private Japanese companies in the same manner as state-to-state reparations[cite: 2]. However, the PDF commentary also points to the Japanese government's consistent stance that all claims involving China were comprehensively settled, and the PRC's own motivation in 1972 to demonstrate a level of goodwill and finality comparable to other post-war settlements[cite: 2].

Notably, following the Supreme Court's judgment and its concluding remarks, a significant development occurred. In October 2009, N reached a settlement with a group of former Chinese forced laborers, including those involved in this case. The company formally apologized for the forced labor of 360 Chinese individuals during the construction of the Anno Hydropower Plant and contributed 250 million yen to establish a new fund intended to provide lump-sum payments as a form of redress[cite: 2].

Conclusion

The Supreme Court judgment illustrates the judiciary's challenging task of interpreting and applying complex post-war international agreements that seek to balance the finality of peace settlements with the pursuit of justice for individual victims of wartime atrocities. While firmly closing the door to court-ordered compensation based on a consistent interpretation of the SFPT framework and its application to the Japan-China relationship via the 1972 Joint Communiqué, the Court also pointedly acknowledged the profound suffering of the victims and signaled an expectation for voluntary reconciliation and relief efforts by the responsible private entity. The decision underscores the enduring tension between legal interpretations designed to secure international peace and the deep-seated human need for acknowledgment and redress of historical injustices.