Warning Letters Across Borders: Japanese Supreme Court on Jurisdiction in International Copyright Disputes

Date of Judgment: June 8, 2001

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

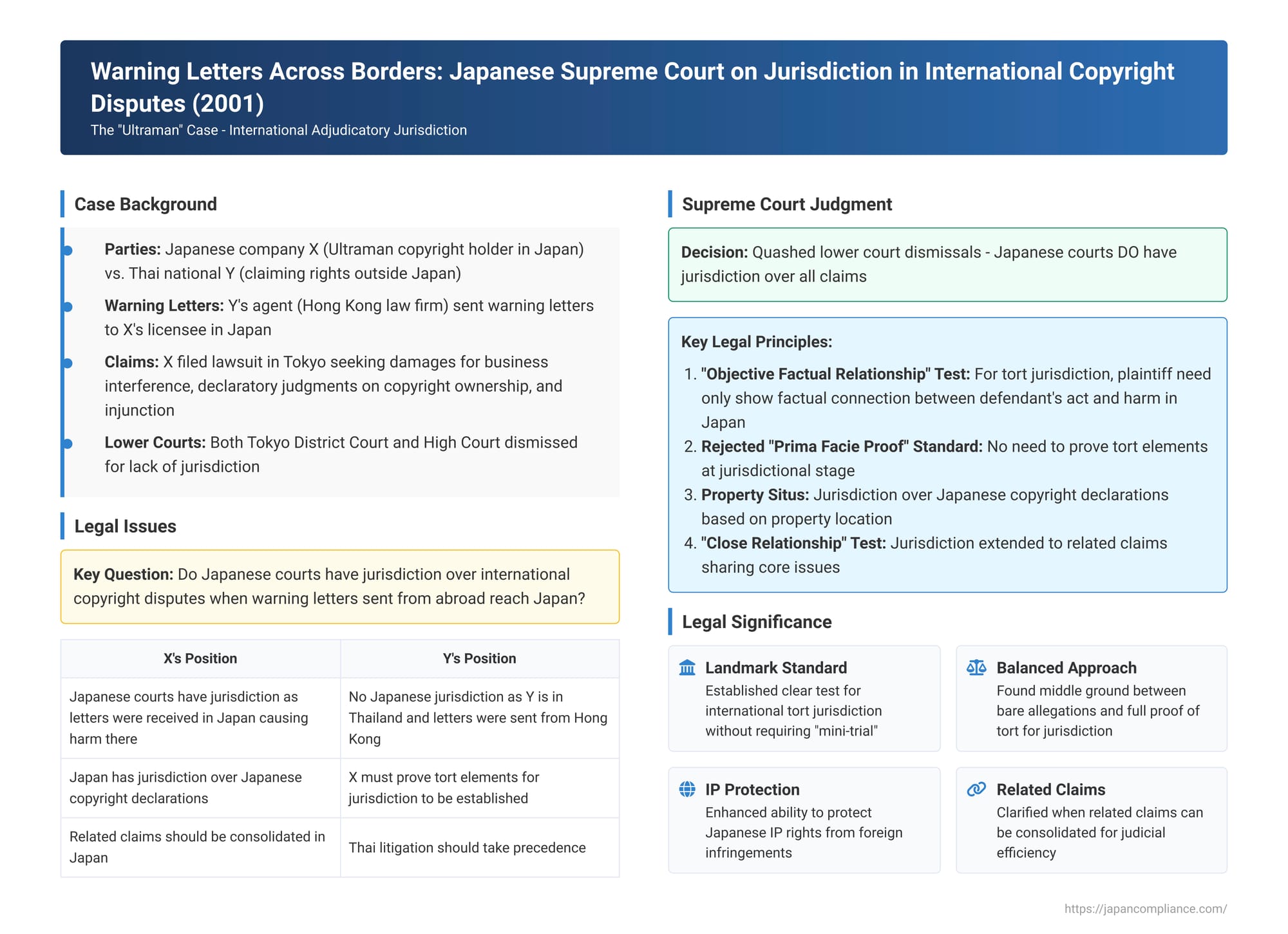

In an interconnected global economy, intellectual property disputes often transcend national borders. A common scenario involves a party in one country sending warning letters to entities in another, alleging infringement of rights. This can lead to complex questions of international adjudicatory jurisdiction: which country's courts have the authority to hear a case arising from such actions? A Japanese Supreme Court decision on June 8, 2001, famously involving the "Ultraman" copyrights, provided significant clarification on how Japanese courts determine jurisdiction in such cross-border tort claims and related matters.

The Factual Background: A Copyright Dispute Spanning Japan, Thailand, and Hong Kong

The case involved a multifaceted dispute over the copyrights to the iconic Ultraman series:

- X (Plaintiff): A Japanese corporation holding the copyright in Japan for the Ultraman TV series and related works ("the Works"). X had licensed another Japanese company, A Corp. (e.g., Bandai), to use the Works in Japan and various Southeast Asian countries.

- Y (Defendant): A Thai national residing in Thailand, who was the president of B Corp. (e.g., Chaiyo Productions). Y asserted that he held exclusive rights (for distribution, production, reproduction, etc.) to the Works in all countries except Japan. This claim was based on a purported contract ("the Contract Document") allegedly made with the original creator.

- The Warning Letters: A Hong Kong law firm, C, acting as an agent for B Corp., sent warning letters ("Warning Letters") to A Corp. and its Southeast Asian subsidiaries. These letters, which reached their recipients, including A Corp. in Japan, alleged that A Corp.'s use of the Ultraman Works infringed upon B Corp.'s exclusive rights.

- X's Lawsuit in Tokyo: X filed a comprehensive lawsuit against Y in the Tokyo District Court, seeking various remedies:

- Claim ① (Tort - Damages): Damages for business interference caused by the Warning Letters sent to Japan.

- Claim ② (Declaratory Judgment): A declaration that Y does not hold the copyright for the Works in Japan.

- Claim ③ (Declaratory Judgment): A declaration that the Contract Document, upon which Y based his rights, was not authentically concluded.

- Claim ④ (Declaratory Judgment): A declaration that X holds the copyright for the Works in Thailand.

- Claim ⑤ (Declaratory Judgment): A declaration that Y does not possess usage rights for the Works.

- Claim ⑥ (Injunction): An injunction to stop Y from making further warning statements.

- Parallel Litigation: X had also initiated legal proceedings against Y in Thailand, seeking an injunction for copyright infringement there and alleging that the Contract Document was a forgery.

Both the Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court had dismissed X's lawsuit in Japan for lack of international adjudicatory jurisdiction. X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Question: Do Japanese Courts Have Jurisdiction?

The central issue was whether Japanese courts could rightfully exercise jurisdiction over Y, a Thai resident, for claims stemming from warning letters related to copyright, especially when the letters were sent from Hong Kong but received and allegedly caused harm in Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Rulings on Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court quashed the lower courts' dismissals and remanded the case to the Tokyo District Court for a trial on the merits, finding that Japanese courts did have jurisdiction over all of X's claims. The Court's reasoning was as follows:

1. Jurisdiction for the Tort Claim (Damages for Warning Letters - Claim ①):

The Court addressed jurisdiction for the tort claim based on Japan's domestic venue rule for torts (Article 15 of the old Code of Civil Procedure, similar in principle to Article 3-3(viii) of the current Code).

- "Objective Factual Relationship" Standard: To establish international jurisdiction for a tort claim against a foreign defendant, it is generally sufficient for the plaintiff to prove the existence of an objective factual relationship (客観的事実関係 - kyakkanteki jijitsu kankei) showing that the defendant's act caused damage to the plaintiff's legally protected interest within Japan.

- The rationale is that if such a factual connection to Japan exists, there is usually a reasonable basis to require the defendant to answer the case on its merits in Japan. From an international perspective of allocating judicial functions, such a connection justifies the exercise of Japanese jurisdiction.

- Application to the Warning Letters: The Supreme Court found it clear that an objective factual relationship existed: Y (through his agent) caused the Warning Letters to be delivered to companies within Japan, and this action allegedly interfered with X's business operations in Japan.

- Rejection of Stricter Proof Standards: The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the High Court's approach, which had required "prima facie proof" (一応の証明 - itchō no shōmei) of the actual existence of a tort (including the absence of any legal justification for sending the letters) at the jurisdictional stage. The Supreme Court stated that:

- Requiring proof of the tort's existence (including elements like unlawfulness or lack of justification, which are matters for the main trial) as a prerequisite for jurisdiction is a flawed premise.

- While simply relying on a plaintiff's bare allegations might be unfair to foreign defendants, demanding full proof of the tort for jurisdiction would contravene the basic structure of litigation (where jurisdiction is determined before the merits).

- The "prima facie proof" standard is itself vague, prone to inconsistent application, and difficult for foreign defendants to predict.

- Conclusion for Claim ①: Japan had international adjudicatory jurisdiction over the tort claim for damages.

2. Jurisdiction for Declaratory Judgment on Japanese Copyright (Claim ②):

The Supreme Court found that the "property" which was the subject of this declaratory judgment—namely, the copyright for the Works in Japan—was located in Japan. Therefore, jurisdiction was affirmed based on the domestic venue rule for the situs of property (Article 8 of the old Code of Civil Procedure; cf. Article 3-3(iii) or (iv) of the current Code). The Court also found that X had a sufficient interest in seeking this declaration, given Y's claims in the parallel Thai litigation about co-owning the Thai copyright.

3. Jurisdiction over Consolidated Claims (Claims ③ to ⑥):

For the remaining claims (declarations about the Contract Document's authenticity, X's copyright in Thailand, Y's lack of usage rights, and an injunction against Y's warnings), the Court applied the principle of jurisdiction over consolidated or related claims (Article 21 of the old Code of Civil Procedure; cf. Article 3-8(i) of the current Code).

- "Close Relationship" Test: For Japanese courts to exercise jurisdiction over additional claims consolidated with a primary claim (for which jurisdiction is established), there must be a "close relationship" (密接な関係 - missetsu na kankei) between the claims. This means they should share substantially the same core issues.

- The rationale is that hearing unrelated claims together would not be a rational allocation of international judicial functions and could unduly complicate and prolong proceedings.

- Application: The Supreme Court found that Claims ③ through ⑥ were all closely related to Claims ① and ②, as they all revolved around the central dispute concerning the ownership of the copyrights in the Works and the validity of Y's asserted exclusive rights under the Contract Document.

- Conclusion for Claims ③-⑥: Japan also had international adjudicatory jurisdiction over these related claims.

4. Parallel Foreign Litigation Not a Bar to Japanese Jurisdiction:

The Supreme Court noted that the claims in the Japanese lawsuit and the ongoing litigation in Thailand were not identical in their subject matter (soshōbutsu). Even though some issues, such as Y's claim to exclusive rights, might overlap, this did not constitute "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) that would make it contrary to fairness or the proper and prompt administration of justice to require Y to defend the suit in Japan.

Significance and Commentary Insights

This "Ultraman case" is a landmark decision in Japanese private international law, particularly for its guidance on establishing jurisdiction in international tort cases.

- Standard for Tort Jurisdiction: The "objective factual relationship" test established by the Supreme Court significantly clarified the threshold for plaintiffs. It means that for jurisdictional purposes, the plaintiff does not need to prove the entire tort, including elements like unlawfulness or the absence of defenses, which are reserved for the trial on the merits. They only need to show a factual link between the defendant's conduct and harm occurring in Japan.

- What Constitutes the "Objective Factual Relationship"? Professor Takeshita's commentary discusses the ongoing interpretation of what specific facts must be proven under this standard. For warning letter cases like this, proof of the sending and receipt of communications that are, on their face, detrimental to the plaintiff's legally protected interests seems to suffice. However, the exact requirements can vary depending on the type of tort (e.g., online defamation, medical malpractice). The line between purely factual elements and those involving legal evaluation can sometimes be nuanced.

- Jurisdiction over Consolidated Claims: The "close relationship" test for consolidated claims provides a practical way to ensure judicial economy while respecting the principles of international jurisdictional allocation.

- Impact on International IP Disputes: This ruling has had a significant impact on how international intellectual property disputes, particularly those involving warning letters or online infringements with a nexus to Japan, are handled by Japanese courts.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2001 decision in this copyright dispute provided crucial clarifications on the standards for asserting international adjudicatory jurisdiction in Japan. By establishing the "objective factual relationship" test for tort claims, the Court adopted a pragmatic approach that avoids a "mini-trial" on the merits at the jurisdictional stage while still ensuring a sufficient connection to Japan. Its rulings on jurisdiction for declaratory judgments based on property situs and for closely related consolidated claims further delineated the scope of Japanese judicial power in complex international litigation. This case remains a vital reference for understanding the jurisdictional landscape in Japan for cross-border disputes.