Voting on Your Own Dismissal? Japanese Supreme Court on "Special Interest" in Board Resolutions Concerning Representative Director Removal

Case: Action for Confirmation of Invalidity of Assignment of Claim, and Action for Payment on Assigned Claim

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of March 28, 1969

Case Number: (O) No. 728 of 1968

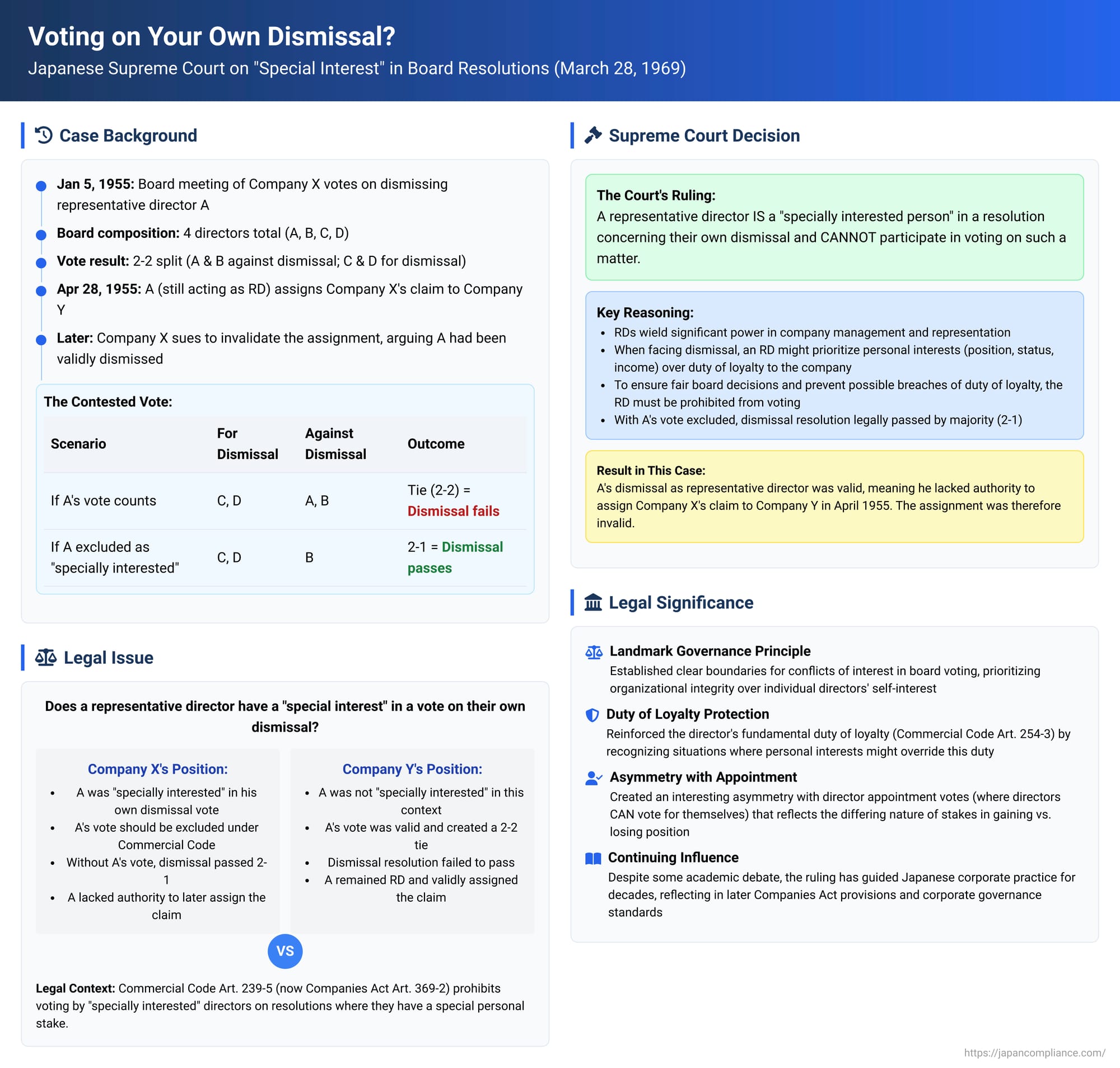

The board of directors plays a pivotal role in the governance of Japanese corporations, making key decisions and overseeing the company's operations. To ensure the fairness and integrity of these decisions, Japanese company law stipulates that a director who has a "special interest" (特別利害関係 - tokubetsu rigai kankei) in a particular resolution cannot participate in the vote on that matter. A critical question that arose before the Supreme Court in a case decided on March 28, 1969, was whether a representative director (RD), the company's top executive, has such a "special interest" when the board is voting on a proposal for their dismissal from that very representative director position.

A Contested Directorship and a Disputed Transaction: Facts of the Case

The case involved two companies, Company X (the plaintiff/appellee, Nitto Starch Chemical Co., Ltd.) and Company Y (the defendant/appellant, Abe Kou Co., Ltd.). These companies had an ongoing business relationship where Company X would have Company Y exclusively sell its starch-based confectionery products, and Company X would, in turn, purchase raw materials from Company Y.

The central dispute revolved around the validity of an assignment of a monetary claim. On April 28, 1955, an individual named A, purportedly acting as the representative director of Company X, assigned a claim held by Company X to Company Y.

However, the authority of A to act as Company X's representative director at that time was contested. This contest stemmed from an earlier board of directors' meeting of Company X, held on January 5, 1955. At this meeting, a proposal was put forward to dismiss A from his position as representative director.

- The board meeting was attended by four directors: A himself (the RD whose dismissal was proposed), and three other directors, B, C, and D.

- When the vote on A's dismissal as RD was taken:

- Directors A and B voted AGAINST the dismissal.

- Directors C and D voted FOR the dismissal.

If A's vote was counted, the result would be a 2-2 tie, meaning the motion to dismiss him would fail.

Company X later initiated legal proceedings, arguing that the assignment of its claim to Company Y on April 28, 1955, was invalid. Its primary contention was that A had already been dismissed as representative director at the January 5, 1955 board meeting. According to Company X:

- In a board resolution concerning the dismissal of a representative director from their post, the representative director in question (A, in this case) qualifies as a "specially interested person" under the provisions of the then-Commercial Code (Article 239, Paragraph 5, as applied to board of directors' meetings by Article 260-2, Paragraph 2 – the substance of which is now found in Article 369, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act).

- As a specially interested person, A was legally barred from voting on the resolution concerning his own dismissal.

- If A's vote was excluded from the tally, the vote would have been 2 (C and D) in favor of dismissal and 1 (B) against. With A's vote excluded, the motion to dismiss A as RD would have passed.

- Consequently, A was no longer the representative director of Company X on April 28, 1955, and therefore lacked the authority to assign Company X's claim to Company Y.

The Lower Courts' Split Decisions

The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court) dismissed Company X's claim, presumably finding that A's dismissal was not validly effected or that he retained authority.

However, the appellate court (Tokyo High Court) reversed this decision. The High Court agreed with Company X's argument, finding that A was indeed a specially interested person in the resolution regarding his dismissal as RD. Therefore, A's vote should not have been counted. With A's vote excluded, the resolution to dismiss him was deemed to have passed. This meant A lacked the authority to subsequently assign Company X's claim, rendering the assignment invalid. Company Y (the recipient of the claim) appealed this High Court ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: RD Cannot Vote on Own Dismissal from RD Post

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision in favor of Company X.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Ensuring Board Fairness and Director Loyalty

The Supreme Court's core reasoning focused squarely on whether RD A qualified as a "specially interested person" in the context of the board resolution to dismiss him from his representative director post:

- RD Facing Dismissal IS a "Specially Interested Person": The Court definitively held that a representative director who is the subject of a board resolution concerning their dismissal from that representative position is considered a "specially interested person" for the purposes of the voting prohibition.

- Rationale – Potential Conflict with Duty of Loyalty: The Supreme Court provided a compelling rationale for this conclusion:

- The representative director is the individual who executes and presides over the company's business operations and holds the authority to represent the company externally (as per then-Commercial Code Article 261, Paragraph 3, and Article 78). They wield significant power and influence over the company's management and control.

- When a board resolution debates the appropriateness of removing an individual from such a powerful position against their will, it cannot necessarily be expected that the representative director in question will be able to cast aside all personal considerations and exercise their vote with complete impartiality, solely in accordance with their duty of loyalty to the company (a duty mandated by then-Commercial Code Article 254, Paragraph 3, and Article 254-2, similar to current Companies Act Article 355).

- On the contrary, the Supreme Court acknowledged the realistic possibility that the representative director might be tempted to act in a way that protects their own personal interests (e.g., retaining their position, status, and emoluments) rather than strictly adhering to what is best for the company.

- Therefore, to prevent such potential breaches of the duty of loyalty and to ensure the fairness and impartiality of the board's resolution-making process, it is appropriate and necessary to prohibit the representative director from exercising their voting rights on a matter in which they have such a significant personal stake.

- Consequence of Excluding the Vote: Since A was a specially interested person, his vote against his own dismissal should not have been counted. The High Court was correct in excluding it. With A's vote removed, the motion to dismiss him as representative director passed by a majority of the remaining eligible votes (2 for dismissal, 1 against).

Analysis and Implications: A Foundational Ruling on Board Governance

This 1969 Supreme Court decision was a landmark in Japanese corporate law, providing crucial clarification on the application of the "special interest" rule in the context of removing a representative director by a board resolution.

- The "Special Interest" Rule (Now Companies Act Article 369, Paragraph 2):

This rule is a fundamental principle of board governance. Its purpose is to safeguard the integrity of board decisions by preventing directors from voting on matters where their personal interests might conflict with, or improperly influence their judgment regarding, the company's best interests. This is directly linked to the overarching duty of loyalty that directors owe to their company (now Companies Act Article 355).

A "special interest" is generally understood to be a personal stake in the outcome of a resolution that is distinct from the general interest shared by all directors or shareholders, and which is significant enough to make it typically difficult for the director to exercise their judgment with complete objectivity and impartiality. Common examples include a director voting on the approval of a self-dealing transaction between themselves and the company (a direct conflict of interest under Article 356 of the Companies Act) or on a resolution to partially release themselves from liability owed to the company (Article 426).

A director deemed to have such a special interest is not only barred from voting but is also typically excluded from the count of directors present for the purpose of determining a quorum for that specific resolution (as per Article 369, Paragraph 1). - Academic Debate Surrounding RD Dismissal and Special Interest:

Despite the Supreme Court's clear ruling in this case, the issue has remained a subject of some academic debate:- Affirmative View (Supporting the Supreme Court): This view, which aligns with the judgment and has largely guided subsequent case law and corporate practice, emphasizes that an RD facing involuntary removal from their powerful and often prestigious position has a very strong personal interest that could easily override their duty to act solely for the company's benefit. The potential loss of power, status, reputation, and remuneration creates a clear conflict.

- Negative View (Arguing the RD Should Be Allowed to Vote): Some scholars have argued against classifying the RD as specially interested in this specific scenario. Their arguments often include:

- Not a True Company-vs-Director Conflict: A vote to dismiss an RD can be seen less as a conflict between the RD's personal interest and the company's interest, and more as a manifestation of an internal power struggle or a fundamental disagreement over management policy among different factions within the board or among shareholder groups they represent. In this view, the RD's desire to remain in office might genuinely stem from a belief that their continued leadership is in the company's best interest.

- Reflection of Shareholder Power Dynamics: Particularly in closely-held companies, directors often represent specific shareholder interests or factions. Excluding the RD's vote in a dismissal scenario could alter the power balance intended by the shareholders when they elected the board members.

- Inconsistency with RD Selection Votes: Generally, a director who is a candidate for appointment or election to the position of representative director is not considered specially interested and is allowed to vote (including voting for themselves). Critics of the Supreme Court's stance on dismissal argue that if a director can vote to gain the RD position, it's inconsistent to bar them from voting to retain it, as similar personal interests are at play. (Proponents of the Supreme Court's view might counter that the threat of involuntary removal from an existing position of power creates a more acute and direct conflict than the aspiration to attain that position).

- Shared Interests Among Other Directors: It's also argued that when one RD's dismissal is on the table, other directors might also have a personal interest – for example, one of them might aspire to become the next RD. Thus, the interest is not necessarily unique to the RD being targeted for dismissal. (Again, proponents of the Supreme Court's view would likely argue that the interest of the director directly facing removal is qualitatively different and more intense).

- Practical Ramifications and Subsequent Developments:

Notwithstanding the ongoing academic discussion, this 1969 Supreme Court ruling has been highly influential. Corporate practice in Japan and subsequent lower court decisions have largely followed the principle that a representative director is excluded from voting on a board resolution concerning their own dismissal from that post.

It's also important to consider what happens if a specially interested director does vote. If their vote was decisive in either passing or defeating the resolution, the resolution is generally considered invalid. However, if the resolution would have achieved the same outcome even without the interested director's vote, it is often held to be valid (a principle affirmed in a later Supreme Court case in 2016 concerning a fisheries cooperative, though the underlying logic is generally applicable). In the 1969 case, RD A's vote created a tie; excluding it resulted in a majority in favor of his dismissal.

This case specifically deals with dismissal from the post of representative director by a board resolution. The dismissal of an individual as a director altogether is a matter for a shareholders' meeting resolution, where different voting rules and considerations of special interest might apply.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of March 28, 1969, established a clear and important principle in Japanese corporate governance: a representative director is deemed to have a "special interest" in a board of directors' resolution concerning their own dismissal from that representative position. Consequently, they are barred from participating in the vote on such a resolution. This ruling prioritizes the overarching objectives of ensuring the fairness of board decisions and upholding the director's fundamental duty of loyalty to the company, deeming these considerations more critical than the representative director's personal interest in retaining their powerful executive post. While the nuances of "special interest" continue to be debated in academic circles, this decision has provided a lasting and practical guideline for corporate board conduct in Japan.