Void Mortgage, Valid Sale? Supreme Court Clarifies Owner's "Party" Status as Key to Protecting Auction Purchasers in Japan

In Japanese real property law, when a mortgage is enforced through a compulsory auction (a form of "security interest execution"), a crucial provision, Article 184 of the Civil Execution Act, comes into play. This article is designed to protect the title acquired by a purchaser at such an auction, even if the underlying mortgage that triggered the auction is later found to have been non-existent or extinguished. The rationale is to ensure the stability and reliability of judicial auctions. However, this protection for the purchaser is not absolute; it is predicated on the idea that the original property owner had a fair opportunity to protect their rights within the auction procedure itself.

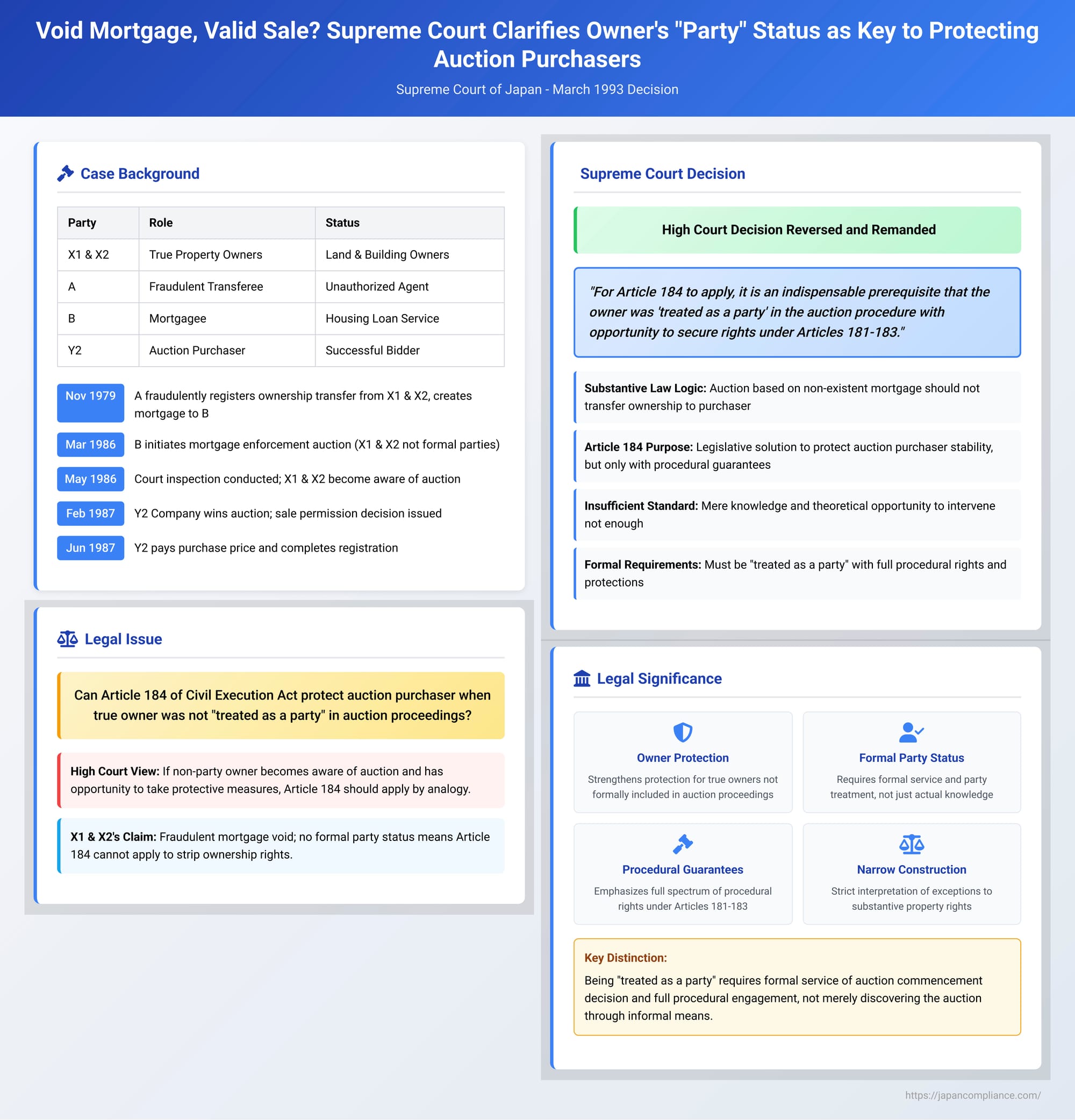

A landmark 1993 Supreme Court of Japan decision delved deep into the nature of this "fair opportunity," specifically addressing whether Article 184 applies if the true property owner was not formally a party to the auction proceedings but merely became aware of them and had some, perhaps limited, chance to intervene. The Court's ruling emphasized that for an owner to lose their property under Article 184 due to a void mortgage, they must have been formally "treated as a party" in the auction, with the attendant procedural guarantees.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved Ms. X1, who owned a parcel of land, and Ms. X2, who owned a building situated on that land (collectively, the "Property"). In November 1979, the ownership of this Property was registered in the name of Mr. A, purportedly based on a sale from X1 and X2. Simultaneously with this registration, Mr. A created a mortgage on the Property in favor of Mortgagee B (a housing loan service company), and this mortgage was also registered.

However, X1 and X2 strongly contended that this initial transfer of ownership to Mr. A was fraudulent and effected without their valid consent. They alleged that Mr. A had improperly used their personal seals, powers of attorney, and other critical documents to complete the registration. (The facts indicate that X1 and X2 became aware of Mr. A's registration by February 1984 at the latest). Subsequently, in September 1983, Mr. A purportedly sold the Property to Mr. Y, and this transfer was also registered. (Mr. Y appears to have been an intermediate owner; the ultimate auction purchaser was a different entity, Y2).

In March 1986, Mortgagee B initiated a mortgage enforcement auction against the Property (the "Said Proceedings") based on the mortgage created by Mr. A. Importantly, X1 and X2, the original owners who contested the validity of A's title (and thus the validity of the mortgage created by A), were not named as formal parties (such as debtor or current owner against whom the auction was directed) in these auction proceedings initiated by B.

Despite not being formal parties, X1 and X2 became aware of the ongoing auction. An on-site inspection of the Property was conducted by a court execution officer in May 1986, and the facts suggest that by this time, at the very least, X1 and X2 knew that the auction was in progress.

The auction proceeded, and in February 1987, Company Y2 was the successful bidder. The execution court issued a "sale permission decision" (売却許可決定 - baikyaku kyoka kettei) in favor of Y2. In June 1987, Y2 paid the purchase price to the court and completed the ownership registration for the Property.

X1 and X2 did attempt to challenge the auction. They filed an execution appeal against the sale permission decision granted to Y2, but their appeal was dismissed. During these appeal proceedings, the court reportedly advised them that their proper course of action was to file a "third-party objection suit" (第三者異議の訴え - daisansha igi no uttae)—a lawsuit where a third party with superior rights can object to the seizure of specific property—and to seek an order from the court to stay (suspend) the execution. However, X1 and X2 did not obtain such a stay order, allegedly because they were unable to provide the security deposit typically required by the court for granting a stay.

The legal battles continued. Company Y2, as the auction purchaser, sued Ms. X2 for eviction from the building on the Property. Ms. X2 defended by arguing that the entire auction was void because the initial transfer of title from her to Mr. A was unauthorized. Nevertheless, Y2's eviction claim was upheld. Concurrently, X1 and X2 had also initiated legal action seeking the cancellation of the registrations in the names of Mr. A and Mr. Y (the intermediate owner), and also seeking Y2's consent to these cancellations. This claim by X1 and X2 was dismissed. X1 and X2 appealed these unfavorable outcomes.

The Tokyo High Court, in ruling on X1 and X2's appeal, dismissed it. The High Court's reasoning was nuanced:

- It acknowledged that Article 184 of the Civil Execution Act generally causes a true owner to lose their rights to property sold at a security auction if they neglect to use the simple objection methods provided by the Act (specifically Articles 181 to 183, which outline how to challenge the auction's basis or seek its stay).

- It stated that the application of Article 184 presupposes that the owner was actually afforded an opportunity to use these statutory remedies. If the owner is not a formal party to the auction proceedings, they might not automatically be aware of the auction and thus might not inherently have this opportunity.

- However, the High Court opined, if a non-party owner does become aware of the auction proceedings through some means and has a sufficient opportunity to take measures to stop them (such as filing for a stay or a third-party objection), then Article 184 should apply to them by analogy to cases where they were formal parties. The High Court found that X1 and X2 fell into this category: they had become aware of the auction relatively early in its progress and had sufficient time to take protective measures. Therefore, Article 184 applied, and Y2 (the auction purchaser) acquired good title.

X1 and X2 appealed this High Court ruling to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court's interpretation of the prerequisites for applying Article 184.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- The Logical Consequence from a Substantive Law Viewpoint: The Court began by stating a fundamental principle: an auction of real property based on a security interest is a procedure for realizing that security interest. Therefore, if the underlying security interest (the mortgage) was non-existent from the outset or was subsequently extinguished, the logical consequence from a purely substantive law perspective is that the sale resulting from such an auction should not effect a transfer of ownership, and the true owner should not lose their property rights.

- The Purpose and Mechanism of Civil Execution Act Article 184: However, the Court immediately acknowledged that strictly adhering to this substantive logic would render the position of purchasers at judicial auctions highly unstable and would severely undermine public confidence in the auction system. To overcome this "difficulty," Article 184 of the Civil Execution Act was enacted. This article provides a legislative solution: it stipulates that if the property owner, despite having been procedurally guaranteed an opportunity to participate in the said real property auction procedure and to assert their rights under Articles 181 to 183 of the Act, nevertheless fails to exercise those rights, then the non-existence or extinguishment of the substantive security interest will not prevent the auction purchaser from acquiring the property. Article 184 is thus designed to legislatively resolve this tension between substantive rights and procedural finality.

- The Indispensable Prerequisite for Applying Article 184 – The Owner Must Have Been "Treated as a Party": Based on this understanding of Article 184's purpose and mechanism, the Supreme Court laid down its crucial holding: For a court to affirm the loss of a property owner's title under Article 184 (an outcome that is contrary to substantive law principles if the mortgage is indeed void), it is an indispensable prerequisite that the owner was "treated as a party" (当事者として扱われ - tōjisha toshite atsukaware) in the said real property auction procedure and was thereby given the opportunity to secure their rights in accordance with the procedures outlined in Articles 181 to 183 of the Civil Execution Act.

- Mere Knowledge and Theoretical Opportunity are Insufficient: Critically, the Supreme Court held that it is not sufficient for the application of Article 184 that the owner merely happened to learn, through some means, that the auction proceedings had been commenced and thus could have taken measures such as applying for a stay of execution. A higher level of formal procedural involvement is required.

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of Article 184 by considering mere knowledge and opportunity to be sufficient. The case was remanded to the High Court for further adjudication. The Supreme Court also noted that upon remand, the High Court should also consider an argument raised by Y2 (the auction purchaser) that the original transfer from X1/X2 to Mr. A might have been a "fictitious display of intention" (通謀虚偽表示 - tsūbō kyogi hyōji) under Article 94 of the Civil Code, and that Y2, as a subsequent bona fide third party, might be protected against X1/X2's claim of invalidity on that separate ground.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1993 Supreme Court decision is of profound importance as it strictly defines the conditions under which Article 184 of the Civil Execution Act operates to protect an auction purchaser's title at the expense of the true owner when the underlying mortgage was void.

- Emphasis on Formal "Party" Status: The most significant aspect of the ruling is its insistence that the true owner must have been formally "treated as a party" in the auction proceedings for Article 184 to apply against them. Mere actual knowledge of the auction, even if coupled with a theoretical opportunity to intervene, is not enough to trigger the preclusive effect of Article 184 that would validate the purchaser's title despite a non-existent mortgage.

- The "Procedural Guarantee leading to Loss of Rights" Theory: The PDF commentary explains that the rationale behind Article 184 is often linked to a theory known as the "procedural guarantee leading to loss of rights" theory (手続保障失権効説 - tetsuzuki hoshō shikkenkō setsu), notably advocated by the legal scholar Katsumi Yamakido. This theory suggests that Article 184 protects auction purchasers by precluding the original owner from later challenging the sale if they were afforded adequate procedural opportunities to raise their objections during the auction process but failed to do so. The Supreme Court's decision, while aligning with the general idea of procedural opportunity, refines it by tying it to formal "party" status.

- What Does "Treated as a Party" Entail? Being "treated as a party" in a mortgage enforcement auction typically involves receiving formal service of the auction commencement decision from the execution court (as per Article 188 of the Civil Execution Act, which applies Article 45, Paragraph 2, regarding service to parties). This formal notification is crucial because it officially informs the recipient of the proceedings and triggers their rights to utilize specific remedies provided by the Civil Execution Act, such as filing an "execution objection" (執行異議 - shikkō igi) under Article 182 to challenge the auction's basis (e.g., by asserting the non-existence of the mortgage). The PDF commentary suggests that receiving such formal service, along with the list of documents submitted by the creditor (as per Article 181, Paragraph 4), provides a qualitatively different level of procedural engagement than merely finding out about the auction through informal means.

- Rationale for Requiring Formal Party Status: The PDF commentary suggests several reasons why the Supreme Court might insist on formal party status rather than just actual knowledge:

- Objectivity and Certainty: Focusing on formal party status provides a clearer and more objective criterion for applying Article 184, rather than relying on subjective assessments of when an owner gained sufficient knowledge or had a "real" opportunity to act. This contributes to procedural stability.

- Narrow Construction of Exceptions to Substantive Law: The Supreme Court explicitly stated that Article 184 creates an outcome (loss of owner's title despite void mortgage) that is contrary to the "logical consequence from a substantive law perspective." Such provisions that override fundamental substantive rights are typically construed narrowly. Requiring full, formal procedural involvement as a "party" before such a consequence attaches aligns with this principle of narrow construction.

- Protection for True Owners Not Formally Engaged: This ruling offers significant protection to true property owners who might not be formally included as parties in a mortgage auction (e.g., if the property is still registered in the name of a previous owner, or if, as in this case, the person who created the mortgage, Mr. A, was the nominal debtor in the security agreement, while X1 and X2 were the true underlying owners whose consent was allegedly bypassed). Even if such owners become aware of the auction, Article 184 may not operate to strip them of their ownership if the mortgage was indeed void and they were not afforded the full procedural rights that come with being formally treated as a party to the proceedings from the outset.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1993 decision clarifies a critical aspect of Article 184 of the Civil Execution Act. For this provision to operate and protect an auction purchaser's title against the claim of a true owner when the enforced mortgage was non-existent or void, it is not enough that the true owner simply knew about the auction and had some chance to intervene. The Supreme Court mandated that the true owner must have been formally "treated as a party" in the auction proceedings, thereby ensuring they received the full spectrum of procedural guarantees and opportunities to assert their rights as envisioned by Articles 181 to 183 of the Act. This ruling underscores the high threshold of procedural involvement required before an owner's substantive property rights can be deemed forfeited in favor of the policy of protecting the stability of judicial auction outcomes.