Variable Insurance and "Paper Losses": A 2000 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on When Damages for Mis-selling Can Be Claimed

Judgment Date: March 17, 2000

Court: Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench

Case Name: Damages Claim Case

Case Number: Heisei 8 (O) No. 1582 of 1996

Introduction: The Allure and Risks of Variable Life Insurance

Variable life insurance policies (変額保険契約 - hengaku hoken keiyaku) offer a blend of life insurance protection and investment potential. Unlike traditional whole life or endowment policies that provide guaranteed cash values and death benefits, the benefits under a variable life policy – particularly the cash surrender value and, in some cases, the death benefit (though often with a minimum guarantee) – fluctuate based on the performance of underlying investments held in a separate account managed by the insurer. These investments typically include assets like stocks and bonds. This structure offers policyholders the possibility of higher returns compared to fixed-rate policies, especially in favorable market conditions. However, it also means that policyholders bear the investment risk: if the underlying investments perform poorly, the policy's cash value can decline, potentially even falling below the total amount of premiums paid.

Given the complex nature and inherent risks of variable insurance, insurers and their sales representatives have a significant legal duty to clearly and adequately explain these risks to potential buyers before a contract is concluded. If an insurer's salesperson breaches this "duty to explain" – for example, by downplaying the investment risks, overstating potential returns, or failing to ensure the client truly understands the product's variable nature – and the policyholder subsequently suffers a financial detriment due to poor market performance, the policyholder might seek damages for mis-selling.

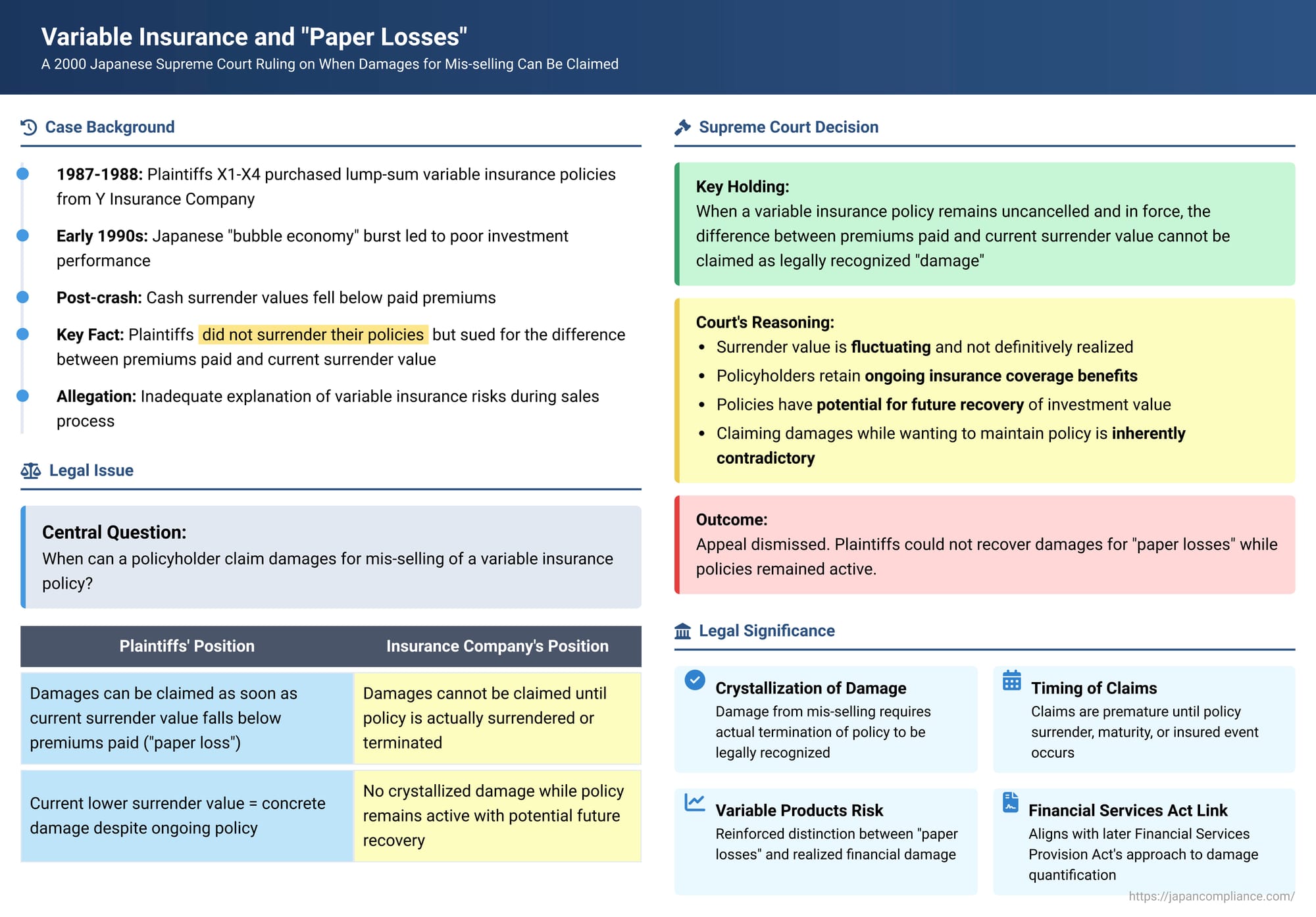

A crucial legal question that arises in such situations is: when can the policyholder actually claim these damages? Specifically, if the policyholder discovers that the current cash surrender value of their ongoing variable insurance policy has fallen below the total premiums they have paid, but they have not yet cancelled or surrendered the policy and wish for the life insurance coverage to continue, can they sue the insurer for the current "paper loss"? Or is such a claim considered premature until the policy is actually terminated and the final financial outcome is known? This pivotal issue, concerning the timing and crystallization of "damage" in mis-selling claims for variable insurance policies that remain in force, was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant decision in the year 2000.

The Facts: Variable Insurance Policies, a Market Downturn, and Allegations of Mis-Selling

The case involved several plaintiffs (X1, X2, X3, and X4) who had purchased whole-life variable insurance policies from Y Insurance Company between March 1987 and March 1988. A key feature of these policies was that the premiums were paid in a single, lump-sum amount at the inception of the contract.

As is characteristic of variable life insurance, the cash surrender values of these policies were linked to the performance of investments held in a separate account. Unfortunately for the plaintiffs, following the "burst of the bubble economy" in Japan in the early 1990s, there was a period of sustained poor performance in the investment markets. As a direct consequence, the cash surrender values of their variable insurance policies declined significantly, eventually falling to levels that were below the substantial lump-sum premiums they had originally paid.

Believing they had been misled at the time of purchase, the plaintiffs alleged that Y Insurance Company's employees, during the sales and solicitation process, had breached their legal duty to adequately explain the inherent risks associated with variable insurance. Specifically, they argued that the risks of the surrender value potentially falling below the amount of premiums paid had not been properly communicated or had been downplayed.

Crucially, despite the poor performance of their policies' cash values, the plaintiffs had not cancelled or surrendered their variable insurance policies. They expressed a desire for the underlying life insurance coverage provided by these policies to continue. Nevertheless, they filed a lawsuit against Y Insurance Company seeking damages. Their claim was based on allegations of tort (improper solicitation) and/or breach of contract (failure to fulfill duties of explanation). The damages they sought were specifically quantified as the difference between the lump-sum premiums they had originally paid and the (lower) cash surrender value of their policies as of the date of the conclusion of oral arguments in the High Court proceedings. Essentially, they were seeking compensation for the current "paper loss" on their ongoing policies.

The Core Legal Issue: Can Damages for Diminished Surrender Value Be Claimed While a Variable Insurance Policy Remains Active and Uncancelled?

The central legal question that the courts had to grapple with was:

When a variable insurance policy remains in full force and effect (i.e., it has not been surrendered by the policyholder, nor has an insured event like death occurred to trigger a final payout), and its cash surrender value is subject to ongoing market fluctuations, can a policyholder successfully sue for and recover damages from the insurer for alleged mis-selling if the current (but still fluctuating) surrender value is less than the total premiums they have paid?

Or, is any alleged "damage" or "loss" in such a situation considered legally speculative, unrealized, or premature until the policy is actually terminated (e.g., by surrender, or upon the death of the insured, or at a maturity date if applicable) and the final, definitive benefit amount is fixed and known?

The Lower Courts' Conflicting Views on the Timing of Damage

The lower courts in Japan came to different conclusions on this critical issue:

- Court of First Instance (Osaka District Court): This court initially found in favor of the plaintiffs (X1-X4). It agreed that Y Insurance Company's employees had indeed breached their duty to adequately explain the risks associated with the variable insurance policies. Consequently, it awarded damages to the plaintiffs, calculated as the difference between the premiums they had paid and the current (lower) surrender value of their policies. However, the court also applied a significant 40% reduction to this amount on the grounds of the plaintiffs' own comparative negligence, finding that they had perhaps somewhat passively or easily relied on the insurer's explanations without sufficient independent consideration.

- Appellate Court (Osaka High Court): Y Insurance Company appealed this decision. The Osaka High Court reversed the first instance judgment entirely and dismissed all of the plaintiffs' claims. The High Court's reasoning was fundamentally different regarding the occurrence of damage. It held that even if it were assumed that Y Company's solicitation methods had been illegal or improper, as long as the insurance contracts themselves remained valid and legally active, and as long as the policyholders (X1-X4) themselves wished for these policies to continue (and had not taken steps to cancel or surrender them), they still legally possessed the status of being entitled to receive the contractual benefits provided by the policies. These benefits included the ongoing life insurance coverage (often with a minimum guaranteed death benefit in variable life policies) and the potential for the surrender value to recover and increase in the future if market conditions improved. Therefore, the High Court concluded, from a legal standpoint for determining damages compensation, it could not yet be said that a quantifiable "damage" or "loss" – in the sense of the difference between paid premiums and current surrender value that the plaintiffs were claiming – had actually occurred or crystallized while the policies remained ongoing.

The plaintiffs then appealed the High Court's dismissal of their claims to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 17, 2000): No Crystallized Damage While Policy Remains Uncancelled and Active

The Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, dismissed the plaintiffs' appeal. It thereby upheld the Osaka High Court's decision that had dismissed their claims for damages.

The Supreme Court's judgment itself was notably brief on this specific point. It focused on the nature of the damages being claimed:

- The Court explicitly noted that the plaintiffs (X1-X4) were seeking damages from the appellee (Y Insurance Company) for an amount equivalent to the difference between the lump-sum premiums they had paid for their respective variable insurance contracts and the cash surrender value of those contracts as of the time of the conclusion of oral arguments in the High Court.

- The Supreme Court then stated that, under the facts as properly established and determined by the High Court, the High Court's ultimate judgment – which concluded that damage equivalent to this claimed difference could not be said to have occurred at that point in time – was correct and could be affirmed as legally justifiable.

The Supreme Court also briefly addressed and dismissed another procedural point raised by the appellants concerning the High Court's alleged failure to exercise its power to seek clarification (釈明権 - shakumeiken) on certain matters, finding no illegality in the High Court's conduct on that front.

Analysis and Implications of the Supreme Court's Ruling

This 2000 Supreme Court decision is highly significant for its clear pronouncement on a critical aspect of mis-selling claims related to ongoing variable insurance policies in Japan. It established an important principle regarding when "damage" is considered to have legally occurred and become quantifiable for the purpose of such lawsuits.

1. "Damage" in Mis-Selling Claims for Ongoing Variable Policies Must Be Realized, Not Merely "Paper Loss":

The core implication of the Supreme Court's ruling (affirming the High Court's more detailed reasoning) is that a mere "paper loss" on an ongoing variable insurance policy does not, in itself, constitute a crystallized, legally compensable damage for the purpose of a tort or breach of contract claim based on alleged improper solicitation or inadequate explanation of risks. A "paper loss" here refers to the situation where the current, fluctuating cash surrender value of the policy is less than the total premiums paid by the policyholder, but the policy itself remains in full force and has not been terminated.

2. Rationale for Denying Premature Damage Claims (Drawing from the Upheld High Court Reasoning and Legal Commentary):

While the Supreme Court's own judgment was concise, the underlying rationale, as articulated by the High Court and discussed in legal commentary (such as the PDF provided with this case), is based on several interconnected points:

- The Fluctuating and Unrealized Nature of Surrender Value in Ongoing Policies: By its very definition, the cash surrender value of a variable life insurance policy is not a fixed or guaranteed amount while the policy is ongoing. It is subject to constant fluctuation based on the performance of the underlying investments in the insurer's separate account. This value only becomes fixed and definitively realized when the policy is actually terminated – for example, through surrender by the policyholder, or upon the occurrence of an insured event like the death of the insured, or at a specified maturity date if it's an endowment-type variable policy. To claim damages based on a snapshot of this fluctuating value at a particular point in time while the policy is still active is to claim for a loss that is not yet certain or finally determined.

- Policyholder Retains Ongoing Contractual Benefits and the Potential for Future Gains: As long as the policyholder chooses not to cancel or surrender their variable insurance policy, they continue to possess and benefit from the contractual rights conferred by that policy. These typically include:

- Ongoing life insurance coverage (which, in the case of whole-life variable policies, often includes a minimum guaranteed death benefit that is payable regardless of how poorly the underlying investments might perform).

- The potential for the policy's cash surrender value to recover and even increase significantly in the future if market conditions improve over the remaining term of the policy.

- The High Court (whose decision the Supreme Court upheld) had reasoned that it would be inherently contradictory for a policyholder to simultaneously express a desire for their insurance policy to continue (thereby retaining these ongoing benefits and future potentials) and, at the same time, claim current damages from the insurer for a "loss" based on a temporary dip in the surrender value. Such a claim is essentially for an unrealized loss while the policyholder still holds the instrument that could potentially lead to future gains or fulfill its primary insurance purpose.

3. When Does "Damage" from Mis-Selling Typically Crystallize for Variable Insurance?

The clear implication of this Supreme Court ruling is that for a claim of damages based on alleged mis-selling that has led to a diminished value in a variable insurance policy, the "damage" or "loss" generally crystallizes and becomes sufficiently certain and quantifiable for legal purposes only when the policy is actually terminated. This termination could occur through:

- Surrender by the policyholder: If the policyholder decides to cancel the policy and take its cash surrender value.

- Occurrence of the insured event: Such as the death of the person whose life is insured, leading to a death benefit payout.

- Maturity of the policy: If it is an endowment-type variable policy that reaches its maturity date.

At the point of such termination, the final financial value received by the policyholder (or their beneficiaries) can be definitively compared to the premiums paid (or some other relevant benchmark, such as what might have been achieved with a more suitable, less risky product) to determine the actual financial loss, if any, that can be attributed to the alleged mis-selling or inadequate explanation of risks.

4. Relevance of Japan's Financial Instruments Sales Act (Now the Financial Services Provision Act):

It is interesting to consider this Supreme Court judgment in the context of legislation that was enacted in Japan shortly after this decision was rendered – namely, the Financial Instruments Sales Act of 2000 (which has since been amended and retitled, now known as the Financial Services Provision Act). As legal commentary (like the PDF provided with this case) points out:

- This Act (e.g., Article 4) imposes a clear statutory duty on sellers of financial products that carry a risk of principal loss to explain important matters regarding those risks to their customers.

- Article 6 of the Act can create strict liability (liability without fault) for financial service providers who breach this duty of explanation.

- Crucially, Article 7 of the Act establishes a legal presumption regarding the amount of damage suffered by a customer due to such a breach: the damage is presumed to be the "amount of loss to principal" (元本欠損額 - ganpon kesson-gaku).

- While life insurance premiums are not traditionally or directly equated with "principal" in the same way as, for example, a principal amount in a savings deposit or a securities investment, the legal commentary suggests that for variable insurance policies, which have a very strong investment component and where the policyholder's funds are exposed to market risk, the total premiums paid by the policyholder could be considered analogous to "principal" for the purposes of applying this Act. The difference between these paid premiums and the final amount received by the policyholder upon the policy's termination (e.g., surrender value or maturity value) could then be considered the "principal loss" under the Act.

- However, even under this statutory framework for assessing damages, the legal commentary argues that if the variable insurance policy remains uncancelled and ongoing, the "principal loss amount" as defined by the Act cannot be definitively determined because the surrender value (or potential future maturity value) is still subject to change based on market performance. Therefore, the fundamental conclusion reached by the Supreme Court in this 2000 case – that a claim for damages based on a current diminished surrender value is premature while the policy is still active – would likely still hold true even under the principles of the Financial Services Provision Act. A definitive, realized loss would generally need to be established.

5. Important Distinction from Cases Involving Rescission or Fundamental Invalidity of the Contract:

It is important to distinguish the scenario in this Supreme Court case from situations where an insurance policy might be subject to rescission (cancellation from the beginning) or might be declared fundamentally void due to more egregious flaws in its formation. Examples could include outright fraud by the insurer, a complete lack of a "meeting of the minds" between the parties on the essential terms of the contract, or perhaps a breach of the duty of disclosure by the applicant so severe as to warrant rescission by the insurer. In such cases, the legal remedy might involve a return of premiums paid as part of the process of unwinding the contract (status quo ante). This is different from the situation in the 2000 Supreme Court case, which concerned a claim for damages where the policyholders, despite alleging mis-selling regarding risks, wished to keep their (presumably otherwise valid) insurance policies in force.

Conclusion

The March 17, 2000, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan provided a crucial and clear clarification regarding the timing and nature of damages that can be claimed by policyholders for the alleged mis-selling of variable life insurance policies.

The Court firmly held that when such a variable insurance policy remains in full force and effect and has not been cancelled or surrendered by the policyholder, the mere fact that the policy's current cash surrender value has fallen below the total amount of premiums paid does not, in itself, constitute a legally recognized and quantifiable "damage" that can form the basis of a successful lawsuit for tort or breach of contract (based on inadequate explanation of risks at the time of sale).

The underlying rationale, strongly supported by the upheld High Court decision and subsequent legal commentary, is that as long as the policy remains active, its surrender value is subject to ongoing market fluctuations, and, more importantly, the policyholder continues to possess the valuable contractual rights conferred by the policy. These rights include ongoing life insurance coverage (often with a minimum guaranteed death benefit in variable life policies) and the inherent potential for the policy's cash value to recover and increase in the future if investment market conditions improve.

This important ruling implies that for damages related to diminished value in such investment-linked insurance products due to alleged mis-selling by the insurer, the financial loss generally needs to be actually crystallized – typically through the termination of the policy via surrender by the policyholder, or upon the occurrence of an insured event like the death of the insured or the maturity of the policy – before it can form the basis of a successful damages claim for the difference between premiums paid and the ultimate value received. The decision underscores the legal principle that "paper losses" on ongoing, fluctuating investment-type instruments are not necessarily treated as realized and compensable damages for legal purposes until the investment position is closed out or the contractual term concludes.