Valuing Unlisted Shares in Appraisal Rights: Japanese Supreme Court Rejects Non-Liquidity Discounts with Income Approach

Judgment Date: March 26, 2015

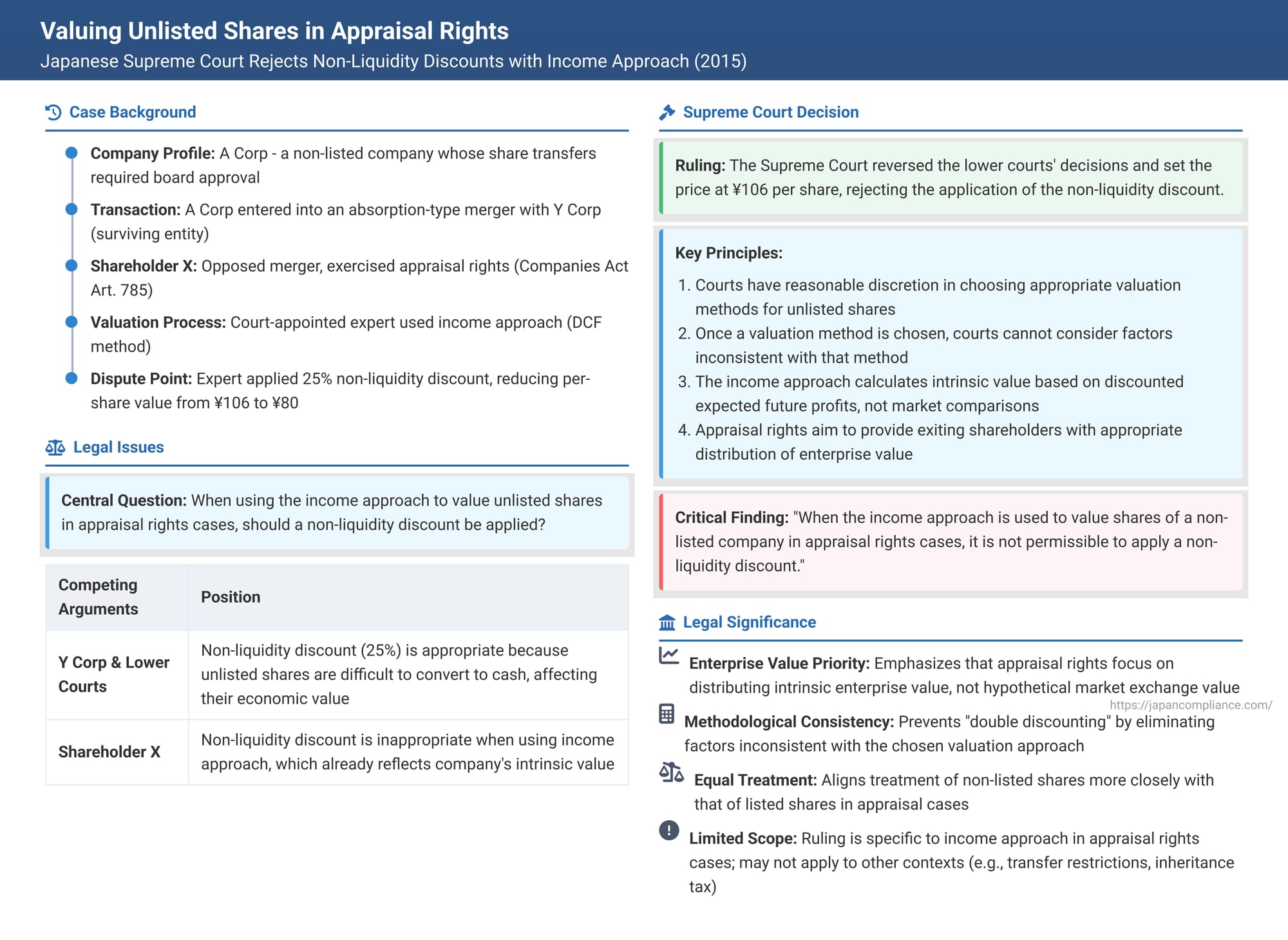

Determining the "fair price" of shares for dissenting shareholders exercising their appraisal rights during corporate reorganizations is a complex task, especially when the company involved is not publicly listed. Unlike listed shares with readily available market prices, valuing unlisted shares often involves various methodologies and subjective judgments. A significant issue that frequently arises is whether a "non-liquidity discount" (or "lack of marketability discount") should be applied to reflect the difficulty of selling such shares. A 2015 Supreme Court of Japan decision provided crucial clarification on this point, particularly when the income approach to valuation is employed.

The Merger and the Dissenting Shareholder's Dilemma

The case involved A Corp, a non-listed company whose articles of incorporation stipulated that any transfer of its shares required the approval of its board of directors. A Corp entered into an absorption-type merger agreement with Y Corp, where Y Corp would be the surviving entity and A Corp would be dissolved.

X, a shareholder of A Corp, opposed this merger. As provided by the Companies Act (Article 785), X exercised the statutory appraisal right, demanding that A Corp (and by succession, Y Corp) purchase X's shares at a "fair price." When the parties could not agree on this price, X petitioned the Sapporo District Court for a judicial determination (under Article 786, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act).

In the District Court proceedings, a court-appointed expert, certified public accountant B, submitted a valuation report.

- Valuation Method Chosen: CPA B deemed the income approach (収益還元法 - shūeki kangen hō) to be the most appropriate method for valuing A Corp's shares. This approach, often implemented as a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, involves forecasting the company's future expected net profits (or cash flows) and discounting them back to their present value using an appropriate capitalization or discount rate.

- Calculated Value (Pre-Discount): Based on this method, CPA B calculated the sum of the present values of A Corp's expected future net profits to be approximately ¥361,583,000.

- Application of Non-Liquidity Discount: CPA B then applied a 25% non-liquidity discount to this derived value. The rationale was that, as a non-listed company, A Corp's shares lacked the ready marketability of listed company shares, making them harder to convert into cash.

- Price per Share: After applying the 25% discount and dividing by A Corp's total outstanding shares (3,387,000), CPA B arrived at a fair buyback price of ¥80 per share.

The Lower Courts' Acceptance of the Discount

The Sapporo District Court adopted CPA B's valuation and determined the fair price to be ¥80 per share. X appealed this decision.

The Sapporo High Court upheld the District Court's ruling. It reasoned that the difficulty in converting A Corp's shares into cash was a factor that inherently affected their economic value. Therefore, even when using the income approach, applying a non-liquidity discount was within the court's reasonable discretion in determining the buyback price. X, still dissatisfied, sought permission to appeal to the Supreme Court, arguing that the application of a non-liquidity discount was improper when the income approach was used.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Shift in Perspective

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated March 26, 2015, reversed the High Court and District Court decisions. It then rendered its own judgment, setting the acquisition price at ¥106 per share. This figure was derived from CPA B's valuation before the application of the 25% non-liquidity discount (approximately ¥361,583,000 divided by 3,387,000 shares).

The Supreme Court's key holdings were as follows:

- Court's Role in Determining "Fair Price": The Court reiterated that when a petition for determining the share price is filed under Article 786, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act, the court must determine a "fair price" based on its reasonable discretion, consistent with the underlying purpose of granting appraisal rights to dissenting shareholders (citing its earlier decision of April 19, 2011 – Case 84 in the user's context).

- Choice of Valuation Method: For non-listed companies, various valuation methodologies exist. The specific method to be used in any given case falls within the court's reasonable discretion.

- Impermissibility of Considering Inappropriate Factors within a Chosen Method: However, once a court deems a particular valuation method to be reasonable and decides to use it for calculating the share price, it is not permissible to then consider factors (like a non-liquidity discount) that are inconsistent with the content, nature, or inherent elements of that chosen valuation method.

- Definition and Nature of Non-Liquidity Discount: A non-liquidity discount is applied because the shares of a non-listed company lack marketability and are less liquid compared to shares of listed companies.

- Nature of the Income Approach (DCF Method): The income approach calculates the present value of shares by discounting the company's expected future net profits using an appropriate capitalization rate. The Supreme Court emphasized that this valuation method, unlike methods such as the comparable company analysis (類似会社比準法 - ruiji kaisha hijun hō), does not inherently include a comparison with market trading prices as a component of its methodology.

- Purpose of Appraisal Rights (Reiteration and Elaboration): The Court re-emphasized that the purpose of granting appraisal rights to shareholders opposing fundamental corporate changes (like mergers) is twofold:

- To provide an opportunity for these dissenting shareholders to exit the company.

- To ensure that shareholders who choose to exit receive an appropriate distribution of the company's enterprise value.

- Incompatibility of Non-Liquidity Discount with the Income Approach in this Context: Considering both the nature of the income approach (which does not rely on market price comparisons) and the fundamental purpose of appraisal rights (to distribute enterprise value), the Supreme Court concluded:

It is not appropriate to further discount the share price derived from the income approach by making a subsequent comparison with market trading prices, which is effectively what applying a non-liquidity discount entails. - Specific Holding for the Case: Therefore, when shareholders of a non-listed company exercise their appraisal rights under Article 785, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act, and the court employs the income approach to determine the share buyback price, it is not permissible to apply a non-liquidity discount.

Unpacking the Valuation Concepts and Legal Reasoning

This Supreme Court decision offers crucial insights into how non-listed shares should be valued in appraisal rights scenarios.

- The Income Approach (DCF): This method focuses on the intrinsic value of a company based on its capacity to generate future economic benefits (profits or cash flows). The value of the shares is seen as the present worth of these anticipated future streams. The expert in this case used projected net profits and a discount rate derived from a CAPM-like formula (incorporating a risk-free rate, market risk premium, industry beta, and a size premium for the smaller, non-listed company).

- Non-Liquidity Discount (Lack of Marketability Discount): This discount is often applied in valuations of private company shares to reflect the fact that they cannot be easily and quickly sold at a known price, unlike publicly traded shares. The argument is that an investor would pay less for an asset that is difficult to liquidate.

- The Supreme Court's Core Logic: The Court's primary rationale for rejecting the non-liquidity discount when the income approach is used in appraisal rights cases rests on two pillars:

- Methodological Inconsistency: The income approach, as understood by the Court, calculates intrinsic value based on future earnings potential, independent of current market trading conditions or comparisons. A non-liquidity discount, however, is fundamentally about marketability and ease of trading, which are external market factors. Introducing this discount after an income-based valuation was seen as mixing incompatible valuation elements.

- Purpose of Appraisal Rights: More fundamentally, the Court stressed that appraisal rights are designed to give dissenting shareholders their fair share of the company's enterprise value. This is distinct from what they might fetch in a quick sale to a third party, where liquidity concerns would indeed lower the price. The goal is to ensure a fair distribution of the company's underlying worth, not just its immediate "exchange value" in a potentially constrained market.

Analysis and Implications

This decision has significant implications for valuing non-listed shares in Japanese corporate law:

- Enterprise Value Trumps Exchange Value in Appraisal Rights: The ruling strongly indicates that, in the context of appraisal rights, the objective is to ascertain the shareholder's pro-rata portion of the company's intrinsic or fundamental enterprise value. It is not merely to replicate the price they might receive in a hypothetical market sale where illiquidity would be a discounting factor. This interpretation aligns the treatment of non-listed shares with that of listed shares in appraisal cases, where market price is often used as a starting point precisely because it is considered (under ideal conditions) to reflect underlying enterprise value.

- The "Double Discounting" Concern: While not explicitly stated as the primary reason by the Supreme Court, legal commentators have pointed out a potential "double discounting" issue. If the discount rate used in the income (DCF) calculation already incorporates premiums for the specific risks associated with a small, non-listed company (as the "size premium" in this case did), then applying an additional, separate non-liquidity discount could effectively penalize the share value twice for similar risk factors. The Supreme Court's decision to disallow the further non-liquidity discount after the DCF valuation (which included a size premium) prevents such double counting. Some argue the Court might have been more direct by citing this as a primary concern.

- Scope and Limitations of the Ruling:

- Specific to the Income Approach: The Court's reasoning is explicitly tied to the nature of the income approach. The decision states that this method, unlike others such as comparable company analysis, does not involve market price comparisons. This might leave open the possibility of considering liquidity aspects if other valuation methods that do rely on market comparables (e.g., using data from listed peer companies) are employed. In such cases, adjustments might be necessary to account for differences in liquidity between the listed peers and the non-listed target company. However, even then, the underlying principle of distributing enterprise value would likely prevent excessive discounting solely for illiquidity beyond what is necessary for a valid comparison.

- Specific to Appraisal Rights Context: The ruling's logic is heavily dependent on the specific statutory purpose of appraisal rights (distributing enterprise value to exiting shareholders). Therefore, this decision does not automatically extend to other legal contexts where non-listed shares are valued. For instance:

- Court Determination of Sale Price for Shares with Transfer Restrictions (Companies Act Article 144): In this scenario, the purpose is often to facilitate a fair "exit" for a shareholder wishing to sell, and the "exchange value" (what a willing buyer would pay a willing seller) might be the more relevant standard. Here, a non-liquidity discount could be justifiable to reflect real-world transaction conditions for illiquid shares. Indeed, lower court decisions in Article 144 cases have sometimes permitted such discounts.

- Inheritance Tax Valuation or Divorce Asset Division: In these contexts, different valuation principles and objectives might apply, potentially allowing for non-liquidity discounts if the aim is to reflect fair market value in a hypothetical sale.

Conclusion

The March 26, 2015, Supreme Court decision represents a significant development in the valuation of non-listed company shares within the framework of shareholder appraisal rights in Japan. By ruling that a non-liquidity discount cannot be applied when the income approach (DCF) is used to determine the "fair price," the Court has emphasized that the primary goal of appraisal rights is to ensure dissenting shareholders receive a fair portion of the company's intrinsic enterprise value, rather than merely a hypothetical, discounted sale price reflecting market illiquidity. This decision promotes a more value-centric approach for shareholders forced to exit due to major corporate reorganizations they oppose, though its principles are carefully tied to the specific valuation method and the unique purpose of the appraisal rights statute.