Valuing Public Interest: How Japan's Supreme Court Assesses Litigation Value in Residents' Lawsuits

Date of Judgment: March 30, 1978

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

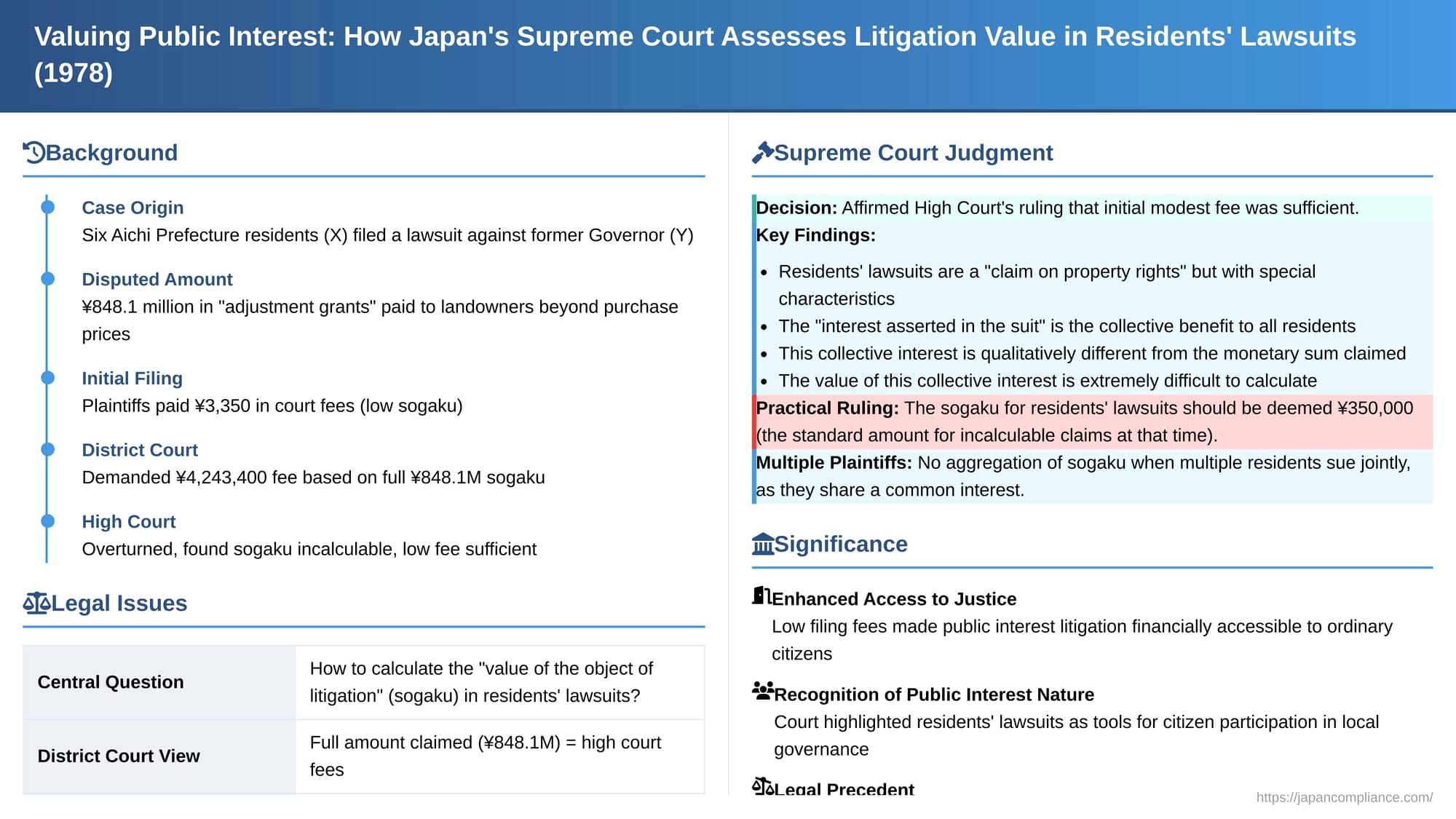

On March 30, 1978, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment concerning a fundamental procedural aspect of "residents' lawsuits" (jūmin soshō)—a unique feature of Japanese law empowering citizens to hold their local governments and officials accountable for financial impropriety. The case, originating from Aichi Prefecture, revolved around the method for calculating the "value of the object of litigation" (sogaku). This value is critical as it determines the court filing fees plaintiffs must pay. The Supreme Court's decision addressed whether the sogaku in such public interest lawsuits should be based on the often very large monetary sums allegedly misused, or on a different understanding of the "interest" pursued by the resident plaintiffs. The ruling established that the sogaku should reflect the collective, not easily quantifiable interest of all residents, thereby ensuring that such lawsuits remain financially accessible.

I. The Alleged Misuse of Public Funds in Aichi Prefecture

The lawsuit was initiated by a group of residents concerned about certain expenditures made by their prefectural government.

The Defendant:

The primary defendant in the case, Y, was the former Governor of Aichi Prefecture.

The Disputed Expenditure:

The core of the dispute was the alleged payment by Y, during his tenure as Governor, of approximately JPY 848.1 million in what were termed "adjustment grants." These grants were reportedly paid to landowners who had agreed to sell their land to Aichi Prefecture for a new housing and urban development project. Notably, these payments were made in addition to the formally agreed-upon purchase prices for the land.

The Plaintiffs and Their Claim:

The plaintiffs, X, comprised a group of six residents of Aichi Prefecture. They exercised their rights under Japan's Local Autonomy Act (LAA) to file a "residents' lawsuit." Specifically, their action was based on Article 242-2, paragraph 1, item 4 of the LAA (as it was worded at that time). This provision allowed residents, under certain conditions, to sue allegedly delinquent local government officials on behalf of their local public entity (in this case, Aichi Prefecture) to seek the recovery of damages caused by illegal financial or accounting actions.

X's contention was that the payment of these "adjustment grants" by Governor Y constituted an illegal expenditure of public funds. They argued that there was no legal obligation for Aichi Prefecture to make such additional payments beyond the negotiated purchase prices for the land. Therefore, they sought a court judgment compelling Y to personally reimburse Aichi Prefecture for the full amount of the JPY 848.1 million allegedly misspent.

II. The Fee Dispute: A High Barrier to Public Interest Litigation?

The substantive claim of illegal expenditure was, at this stage, overshadowed by a critical procedural dispute concerning the court filing fees.

Initial Filing and Fee Paid by Plaintiffs:

When X filed their lawsuit at the Nagoya District Court, they attached revenue stamps (the standard method for paying court fees in Japan) worth JPY 3,350 to their complaint. This amount would typically correspond to a lawsuit with a relatively low sogaku (value of the object of litigation).

District Court's Assessment and Order for Additional Fees:

The Nagoya District Court, serving as the court of first instance, took a significantly different view on the sogaku. It determined that the sogaku of X's lawsuit should be the full JPY 848.1 million that X were seeking to recover for Aichi Prefecture. Based on this extremely large sogaku, the District Court calculated that the correct filing fee was a staggering JPY 4,243,400. Consequently, the court ordered X to pay the substantial shortfall. X, the resident plaintiffs, did not comply with this order for additional payment.

District Court's Dismissal of the Lawsuit:

Due to the non-payment of the assessed fee shortfall, the Nagoya District Court dismissed X's lawsuit. The court's reasoning was that a residents' lawsuit brought under the then-applicable LAA Article 242-2, paragraph 1, item 4, is a form of third-party litigation (statutory legal standing) where the plaintiff residents effectively stand in the shoes of, or act as representatives for, the local government (the "principal" whose rights are being asserted). From the perspective of this principal, Aichi Prefecture, the claim was clearly for a tangible economic benefit—the recovery of JPY 848.1 million. Therefore, the District Court concluded, the sogaku should be calculated based directly on this claimed monetary amount, just as it would if the Prefecture itself were suing for damages.

High Court's Reversal and Remand:

X appealed the District Court's dismissal to the Nagoya High Court. The High Court overturned the District Court's decision and remanded the case for a hearing on its merits. While the High Court agreed with the District Court's initial premise that the claim was, in its form, a "claim on property rights," it adopted a markedly different approach to determining the sogaku for fee purposes.

The High Court reasoned that the underlying interest being pursued in a residents' lawsuit should be viewed substantively as an interest belonging to all residents of the local government collectively, rather than just the financial interest of the local government as an abstract entity. It found that expressing this collective, diffuse interest of the entire populace in precise monetary terms was extremely difficult, if not practically impossible. Therefore, the High Court concluded that the sogaku, from the perspective of the resident plaintiffs and their collective interest, was effectively incalculable. This led to the conclusion that the initial, modest stamp fee paid by X (which would correspond to a minimum deemed sogaku for such incalculable cases under the procedural rules) was sufficient.

It was this High Court decision, which had revived X's lawsuit, that Y, the former Governor, appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Definitive Stance on Sogaku in Residents' Lawsuits

The Supreme Court of Japan, in its judgment of March 30, 1978, affirmed the Nagoya High Court's decision to reverse the dismissal of the lawsuit. While the High Court had based its sogaku reasoning on the "incalculable value" of the residents' collective interest, the Supreme Court provided a more nuanced analysis that, while leading to a similar practical outcome regarding the fee, refined the jurisprudential basis for it.

A. Characterization as a "Claim on Property Rights"

The Supreme Court began by agreeing with the consistent finding of both lower courts that a residents' lawsuit seeking damages (i.e., financial reimbursement to the local government) should be classified, for the purposes of applying the Civil Procedure Costs Act, as a "claim on property rights" (zaisanken-jō no seikyū). The Court reasoned that this characterization is appropriate because the lawsuit, at its core, demands the payment of a specific sum of money from the defendant to the local government.

The PDF commentary accompanying this case notes that this classification has not been without debate. Some legal scholars have argued that, given the overarching public interest nature of residents' lawsuits and their aim of ensuring lawful administration rather than securing private gain for the plaintiffs, they should more appropriately be classified as "non-property rights claims" (hi-zaisanken-jō no seikyū). The commentary also touches upon the potential implications of the 2002 revision of the Local Autonomy Act. This revision significantly altered the nature of the Item 4 residents' lawsuit (the type at issue in this 1978 case), changing it from a direct derivative action for damages by residents to an "obligation-imposing suit" (gimuzuke soshō) where residents primarily sue to compel the local government to itself take action (e.g., sue the responsible officials for damages). This legislative change has led to further academic discussion on whether such new-style Item 4 lawsuits still retain the character of "claims on property rights" for sogaku purposes, or if the indirect nature of the claim now pushes them more firmly into the "non-property rights" category.

B. Identifying the Crucial "Interest Asserted in the Suit"

Having affirmed its classification as a property rights claim, the Supreme Court stated that the crucial question for sogaku calculation was the correct identification of the "interest asserted in the suit" (uttae o motte shuchō suru rieki). This phrase, drawn from procedural law (Civil Procedure Costs Act, Article 4, paragraph 1, and Code of Civil Procedure, Article 22, paragraph 1, at the time), serves as the legal yardstick for measuring the value of a claim for fee purposes.

C. The Unique Purpose and Nature of Residents' Lawsuits: A Deeper Dive

The Supreme Court then embarked on a detailed and influential explanation of the distinctive characteristics, purpose, and legal nature of residents' lawsuits as established under LAA Article 242-2:

- Protecting Collective Resident Interests: The Court emphasized that these lawsuits are specifically designed by the legislature to enable residents to prevent or seek rectification of illegal financial or accounting actions (or unlawful failures to act) committed by the executive organs or officials of their local public entity. Such illegalities are understood to ultimately cause harm to the collective interests of the entire body of residents who constitute that local public entity.

- A Tool for Citizen Participation and Ensuring Good Local Governance: Residents' lawsuits are not merely private disputes; they are a vital instrument of citizen participation in local governance, deeply rooted in the constitutional principle of local autonomy. They empower ordinary residents to demand judicial review and correction of fiscal improprieties, thereby aiming to ensure the proper, lawful, and transparent administration of local public finances. The PDF commentary reinforces this by noting that the Supreme Court, in this and other judgments, has described residents' lawsuits as a form of "political participation" (sanseiken) specifically granted to residents by law. While distinct from direct electoral rights like voting, these lawsuits provide a crucial mechanism for residents to act as watchdogs over the financial integrity of their local government.

- Residents as Representatives of the Public Interest, Not Personal Gain: A key aspect highlighted by the Supreme Court is the motivation and role of the plaintiff resident. When residents file such a lawsuit, they are not acting primarily for their own personal, individual financial gain. Nor are they acting merely as simple agents or proxies for the local government entity itself in a narrow, proprietary sense. Instead, resident plaintiffs act as representatives of the broader public interest, advocating for the proper management of public funds and the lawful conduct of fiscal administration for the benefit of all residents of that community, including themselves.

- Judgment's Binding Effect on All Residents: Consistent with this public interest nature, the judgment rendered in a residents' lawsuit is generally understood in Japanese law to have a binding effect that extends beyond the particular plaintiffs who initiated the action; it typically binds all residents of the local public entity concerned.

- Derivative Form as a Technical, Procedural Device: The specific type of residents' lawsuit at issue in this 1978 case (under the old LAA Article 242-2, Item 4) was structured as a derivative action—where residents sue "on behalf of" the local government to enforce a claim (e.g., for damages) that the local government itself possesses against an allegedly delinquent official. However, the Supreme Court strongly emphasized that this derivative form is largely a technical, procedural device chosen by the legislature for pragmatic reasons. Substantively, the Court found, these public law residents' lawsuits differ significantly in their nature and purpose from typical private law derivative actions, such as a creditor suing on behalf of a debtor under Article 423 of the Civil Code. In residents' lawsuits, the central objective is for the residents, from their unique standpoint as members of the affected community and guardians of the public purse, to demand that officials rectify illegal acts and ensure that any financial loss to the public entity is made good. The derivative form, the Court suggested, was adopted primarily as a matter of litigation technique to achieve this overarching public interest objective. The PDF commentary elaborates on this point, suggesting that the residents' right to seek the correction of illegal financial acts is conceptually distinct from the local government's own underlying claim for damages against the official. The derivative form is employed, in this view, not only to empower residents but also to prevent a confusing or inefficient situation where multiple, potentially conflicting, legal proceedings might arise if residents and the local government were to pursue separate but related claims.

D. Calculating the Sogaku Based on the Collective Resident Interest

Drawing from its detailed understanding of the special purposes and characteristics of residents' lawsuits, the Supreme Court then laid down its rule for calculating the sogaku:

- The "interest asserted in the suit" for sogaku calculation purposes must be understood substantively, not just formally. This interest, the Court declared, is the collective benefit that all residents of the local public entity (including the named plaintiffs) stand to receive when the local government's financial loss (caused by the alleged illegal act) is recovered.

- The Court reasoned that this collective benefit accruing to the entire populace of the local entity is, by its very nature, qualitatively different from, and not simply identical to, the direct monetary sum that the local government itself would recover (i.e., the JPY 848.1 million claimed on behalf of Aichi Prefecture in this case). Furthermore, the Court found it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to identify any objective and rational basis for assigning a specific, quantifiable monetary value to this diffuse, collective benefit enjoyed by all residents.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that, by analogy to Article 4, paragraph 2 of the Civil Procedure Costs Act (which, at that time, provided a specific deemed sogaku for non-property claims or for property claims whose value was incalculable), the sogaku for a residents' lawsuit of this type should be deemed to be JPY 350,000. (This was the prevailing deemed amount for such cases under the law at that time. The PDF commentary notes that under current law, the deemed sogaku for non-property claims, or for property claims where calculation is extremely difficult, is JPY 1.6 million ).

E. No Aggregation of Sogaku When Multiple Residents Sue Jointly

The Supreme Court also addressed the situation, pertinent to this case, where multiple residents join together as co-plaintiffs in a single residents' lawsuit.

- It held that because residents initiate these lawsuits under a special statutory provision, in their capacity as members of the local community, and they are acting for the collective benefit of all residents, the "interest asserted in the suit" by each individual co-plaintiff is essentially identical and shared among them.

- Consequently, even if several residents (like the six plaintiffs in this case) jointly file the lawsuit, their individual (deemed) sogaku amounts should not be aggregated under the then-applicable Code of Civil Procedure Article 23, paragraph 1 (which generally required the aggregation of claim values for multiple claims or parties in other contexts).

- Instead, the total sogaku for the joint residents' lawsuit remains a single, deemed amount of JPY 350,000, regardless of the number of plaintiff residents who have joined the action. (It is worth noting that the current Code of Civil Procedure Article 9, paragraph 1 also generally requires aggregation but contains an important proviso stating that aggregation is not done if the interest asserted in the suit is common to each claim or party).

Final Decision of the Supreme Court:

Based on this comprehensive reasoning, the Supreme Court found that the Nagoya High Court's decision—which had determined that the initial, modest fee paid by X was sufficient, based on its slightly different reasoning that the sogaku was simply incalculable—was correct in its ultimate outcome (i.e., that the case should not have been dismissed for insufficient fees). The Supreme Court therefore dismissed Y's (the former Governor's) appeal.

IV. Legal and Practical Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's 1978 decision in this Aichi Prefecture residents' lawsuit case is widely regarded as a landmark ruling that has had profound and lasting effects on the landscape of public interest litigation in Japan.

Facilitating Access to Justice in Public Interest Litigation:

- The most significant impact of the decision was that it substantially lowered the financial barrier for ordinary citizens wishing to engage in residents' lawsuits. By establishing that these suits would carry a modest, deemed sogaku (which was JPY 350,000 at the time of the judgment) and, crucially, by explicitly rejecting the aggregation of this amount even when multiple residents sue jointly, the Supreme Court ensured that the initial court filing fees for such actions would remain relatively low and affordable for most people.

- This was a vital step in making these important public accountability lawsuits practically accessible. If the sogaku had been tied directly to the often very large sums of public money involved in allegations of illegal expenditure (as the District Court had initially ruled in this case), the resulting court fees could have been prohibitively expensive. Such high fees would have effectively deterred most residents, regardless of the merits of their case, from exercising their statutory right to challenge perceived fiscal wrongdoing by local officials. The PDF commentary notes that the District Court, in adopting the "claimed amount theory" (linking sogaku to the sum the local government stood to recover), had argued that potentially high fees were not an undue restriction on access to justice due to the availability of options like litigation aid, the possibility of cost-sharing among multiple plaintiffs, and the potential for recovery of litigation expenses from the local government if the suit were successful. However, the Supreme Court's ultimate approach clearly prioritized ensuring broader accessibility from the outset.

Recognizing and Emphasizing the Unique Nature of Residents' Lawsuits:

- The judgment's detailed and careful analysis of the underlying purpose and distinctive legal character of residents' lawsuits served to underscore their special status within the Japanese legal system. By clearly distinguishing them from ordinary private law derivative actions (like creditor actions) and by emphasizing their fundamental role as a tool for citizen participation in ensuring local fiscal probity and protecting the collective interests of all residents, the Supreme Court provided a strong and enduring jurisprudential basis for treating them differently for various procedural purposes, including the crucial calculation of sogaku.

- This explicit recognition of their "public interest" or "participatory democracy" dimension was a key element in the Court's reasoning. It directly supported the conclusion that the "interest asserted by the plaintiff" in such a suit should not be simplistically equated with the direct financial claim that the local government itself might possess.

Impact of Subsequent Legislative Changes on the Doctrine:

- As the PDF commentary pertinently points out, the Local Autonomy Act, which provides the statutory basis for residents' lawsuits, underwent a significant revision in 2002. This revision notably altered the nature of the Item 4 residents' lawsuit (the type of action that was at issue in the 1978 Supreme Court case). Under the revised law, instead of residents directly suing allegedly delinquent officials for damages on behalf of the local government (the old derivative action model), the new framework generally requires residents to first formally demand that their local government itself take appropriate action (e.g., initiate a lawsuit against the officials to recover damages). If the local government then fails to act in response to this demand, residents can subsequently file what is known as an "obligation-imposing lawsuit" (gimuzuke soshō) against their local government, seeking a court order to compel it to pursue the claim against the responsible officials.

- This structural change in the nature of the lawsuit has inevitably sparked considerable debate among legal scholars in Japan. A key question is whether these new-style Item 4 "obligation-imposing suits" still qualify as "claims on property rights" for sogaku calculation purposes, or if their more indirect nature means they should now be definitively treated as "non-property rights claims" (which, under current rules, also attract a deemed sogaku, albeit a different amount from that in 1978). The Supreme Court's original reasoning in the 1978 case, which based the "property rights claim" characterization partly on the fact that the suit involved a "demand for payment of a specific sum of money," might still be considered relevant by some. Others may argue that a different analysis is now warranted given the more indirect nature of the claim under the revised LAA. This remains an area of ongoing legal discussion.

Comparison with the Treatment of Shareholder Derivative Suits:

- It is interesting to note, as the PDF commentary does, that shareholder derivative suits in the realm of corporate law—which bear a certain structural resemblance to the old-style residents' lawsuits in that they involve a representative (a shareholder) suing on behalf of an entity (a company) against allegedly delinquent directors—were later accorded a specific legislative solution for sogaku calculation. A revision to Japan's Commercial Code (the principles of which are now found in the Companies Act, specifically Article 847-4, paragraph 1) explicitly provided that for the purpose of calculating the sogaku, shareholder derivative suits are deemed to be "non-property rights claims." This legislative intervention ensures that shareholder derivative suits also attract a modest, fixed deemed sogaku, thereby promoting access to justice in the context of corporate governance litigation. This parallel development, though achieved through direct legislation rather than judicial interpretation, perhaps reflects a similar underlying policy concern in Japanese law about ensuring that the cost of litigation does not become an undue barrier in important areas of representative or public-interest-oriented lawsuits.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's judgment of March 30, 1978, in the Aichi Prefecture residents' lawsuit case, stands as a pivotal decision that has profoundly shaped the landscape of public interest litigation in Japan. By thoughtfully analyzing the unique nature and democratic purpose of residents' lawsuits—recognizing them as a form of citizen participation aimed at ensuring local fiscal accountability—the Court established crucial and enduring principles for the calculation of the "value of the object of litigation" (sogaku).

The landmark ruling that the sogaku in such cases should be based on a modest, deemed value representing the collective, not easily monetized, interest of all residents—and, very importantly, that this value should not be aggregated even when numerous residents sue jointly—was instrumental in enhancing the practical accessibility of these vital legal tools for ordinary citizens.

While subsequent legislative changes to the structure of residents' lawsuits have introduced new dimensions to the legal debate, this 1978 Supreme Court decision remains a cornerstone of Japanese administrative and procedural law. It is celebrated for its clear recognition of the distinct public interest dimension of such litigation and for its pragmatic approach to ensuring that procedural rules, particularly those concerning court filing fees, do not unduly hinder citizens' laudable efforts to hold their local governments accountable and to safeguard the integrity of public finances.