Valuing Assets for Monetary Restitution in Bankruptcy Avoidance: A 1986 Japanese Supreme Court Decision on Timing and Judicial Guidance

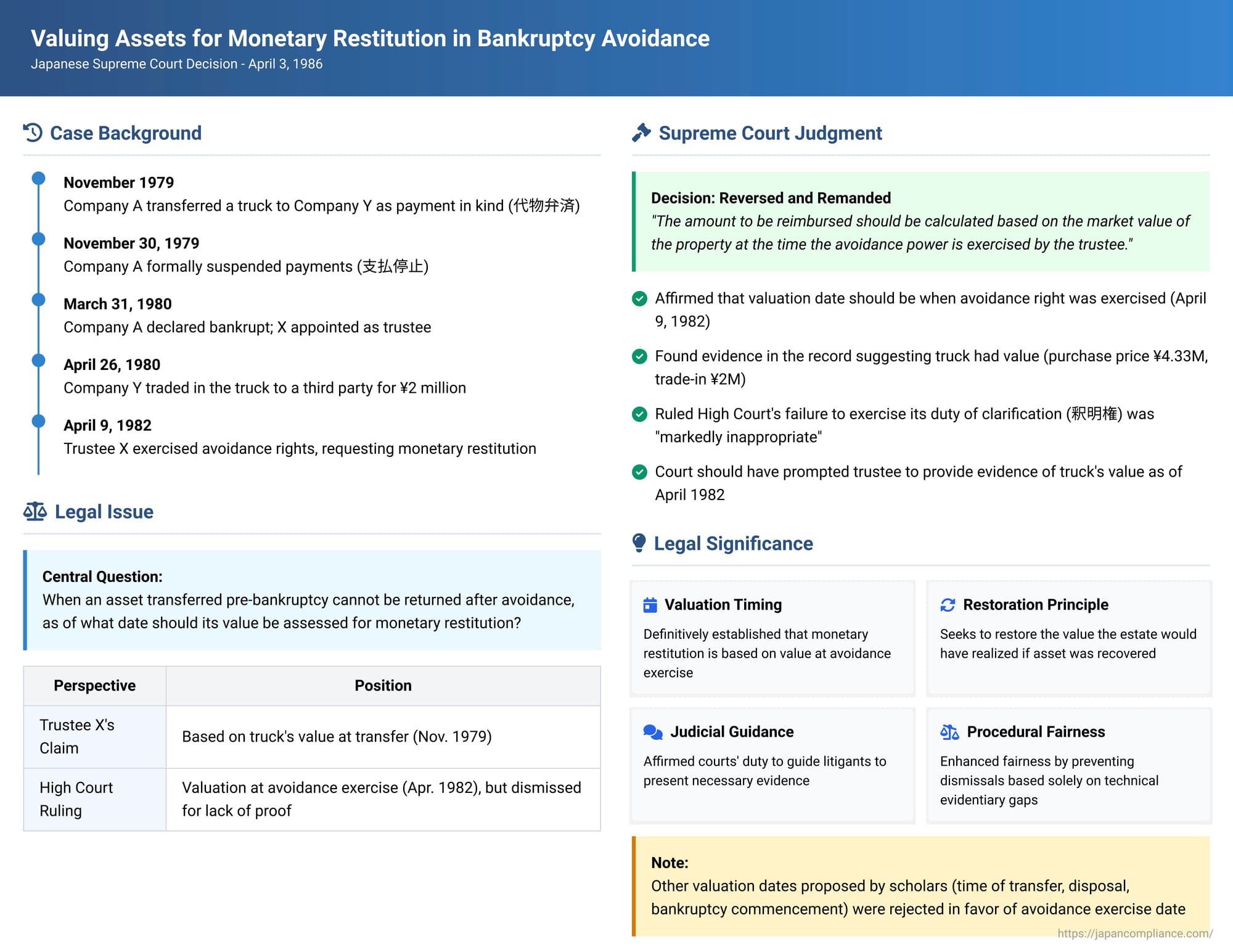

When a bankruptcy trustee in Japan successfully "avoids" (否認 - hinin) a pre-bankruptcy transaction, the primary goal is to restore the bankruptcy estate to the financial position it would have been in had the detrimental transaction not occurred. If the actual asset transferred by the bankrupt can be returned, it is restored to the estate. However, if the asset is no longer available (for instance, if it has been sold by the recipient or consumed), the trustee is entitled to demand monetary restitution of its value (価額償還 - kagaku shōkan) from the beneficiary of the avoided transaction. A critical question then arises: as of what date should this value be assessed, especially if the asset's value has fluctuated over time? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from April 3, 1986, provided a clear answer to this question and also shed light on a court's duty to guide litigants in presenting necessary proof.

Factual Background: The Truck, the Set-Off, and the Avoidance Claim

The case involved A Co., which owed Y Co. a trade debt of over 3.08 million yen. In early November 1979, facing financial difficulties, A Co. and Y Co. came to an agreement: A Co. would transfer one of its trucks (the "subject truck") to Y Co. as a "payment in kind" (代物弁済 - daibutsu bensai) in lieu of satisfying 1.5 million yen of the outstanding debt. A Co. delivered the truck to Y Co. around this time. This act of delivering the truck is referred to as the "removal act."

Shortly thereafter, on November 30, 1979, A Co.'s representative convened a meeting of the company's creditors and formally announced that A Co. was unable to meet its debt obligations. This announcement constituted a "suspension of payments" (支払停止 - shiharai teishi), a key indicator of insolvency.

Following these events, a bankruptcy petition was filed against A Co. on January 21, 1980. A Co. was formally declared bankrupt on March 31, 1980, under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act, and X was appointed as its bankruptcy trustee. It transpired that Y Co., the recipient of the truck, had already disposed of it; on April 26, 1980, Y Co. had traded in the subject truck to a third party, B, as part of a transaction to purchase a new vehicle.

Trustee X subsequently initiated a lawsuit against Y Co. By means of a complaint served on Y Co. on April 9, 1982, trustee X formally exercised the right of avoidance against the earlier transfer of the truck (the daibutsu bensai). Since the truck itself was no longer available for return in specie, the trustee sought monetary restitution. X claimed 1,564,995 yen, which X alleged was the truck's depreciated book value at the time of the "removal act" in November 1979, plus damages for delay.

The Sendai High Court, Akita Branch (acting as the appellate court in this instance), found that the conditions for avoiding the transfer of the truck as a non-obligatory preferential act under Article 72, item 4, of the old Bankruptcy Act were indeed met (this provision applied to acts such as payments in kind not made in the ordinary course of business or for which the debtor was not obliged, during a crisis period). However, the High Court then addressed the issue of monetary restitution. It ruled that the correct valuation date for determining the amount of monetary restitution should be the time the bankruptcy trustee exercises the right of avoidance (i.e., April 9, 1982, the date the complaint formally asserting avoidance was served on Y Co.). The High Court then proceeded to dismiss trustee X's claim for monetary restitution entirely, on the grounds that X had failed to provide any proof of the truck's value as of that specific later date (April 1982). X had based the claim on the truck's value at the time of the initial transfer in November 1979.

Trustee X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other points, that the High Court had erred by not prompting X to provide evidence of the truck's value as of the date of the avoidance exercise, thereby improperly failing to exercise its judicial duty of clarification (釈明権の行使 - shakumeiken no kōshi).

The Legal Issue: Determining the Valuation Date for Monetary Restitution in Avoidance Cases

When an asset transferred pre-bankruptcy is no longer available for return after a successful avoidance by the trustee, the valuation date for monetary restitution becomes critical. If the asset's market value has changed between the time of the original transaction, the time of bankruptcy commencement, the time the trustee exercises avoidance, or the time of judgment, the choice of valuation date can significantly affect the amount recovered for the bankruptcy estate and the liability of the recipient of the avoided transfer. Legal scholars had proposed various dates, each with different theoretical underpinnings.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Valuation at the Time of Avoidance Power Exercise

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of April 3, 1986, reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings.

Valuation Date for Monetary Restitution Confirmed

The Supreme Court first reaffirmed its consistent position on the valuation date:

When a bankruptcy trustee's exercise of the right of avoidance results in a situation where the return of the actual property in specie is impossible, and monetary restitution of its value is to be made instead, the amount to be reimbursed should be calculated based on the market value (時価 - jika) of the property at the time the avoidance power is exercised by the trustee.

The Court stated that this interpretation is based on the "legal intent" (法意 - hōi) of Article 77 of the old Bankruptcy Act (a provision concerning the effects of avoidance, broadly corresponding to Article 167 of the current Bankruptcy Act). The underlying rationale, as explained in prior Supreme Court decisions cited by the Court (e.g., a November 17, 1966 judgment), is that the monetary restitution should aim to restore to the bankruptcy estate the value that it would have been able to realize if the asset had been successfully recovered by the trustee at the moment the avoidance took effect and then subsequently liquidated in an orderly manner by the trustee for the benefit of creditors.

The Court's Duty to Prompt for Proof (Duty of Clarification - Shakumeiken no Kōshi)

This was the pivotal point on which the High Court's decision was overturned:

- The Supreme Court noted that the evidentiary record already contained information about the truck's value at different points in time. A Co. had originally purchased the truck for 4.33 million yen approximately four years and eight months before trustee X exercised the avoidance power in April 1982.

- Trustee X had submitted documentary evidence indicating that the truck's depreciated book value at the time of its removal by Y Co. (November 1979) was the claimed 1,564,995 yen.

- Furthermore, Y Co. itself had asserted (and provided supporting documentation) that it had traded in the truck for 2 million yen on April 26, 1980.

- Given this existing evidence, the Supreme Court found it "unthinkable" that the subject truck's market value at the time trustee X exercised the avoidance power (April 9, 1982) would have been zero. It was also reasonable to assume that proving its value as of that date would have been possible.

- The Supreme Court observed that during the High Court proceedings, the primary focus of the trial and evidence (particularly witness testimony) had been on establishing the factual grounds for avoidance (e.g., whether A Co. had indeed suspended payments when the truck was transferred), rather than on the precise valuation of the truck as of the later date of the avoidance exercise. Y Co., for its part, had not actively disputed the valuation for that specific date or offered counter-evidence.

- In such circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that it was "markedly inappropriate" for the High Court, after affirming that the trustee had a right to monetary restitution in principle, to then immediately dismiss the trustee's claim solely for lack of proof of value as of the (correctly identified) avoidance date, without first prompting trustee X to submit the necessary evidence for that valuation.

- The Supreme Court held that the High Court should have exercised its duty of clarification to encourage trustee X to provide proof of the truck's market value as of April 9, 1982. Its failure to do so constituted an improper exercise of this judicial duty, leading to an incomplete trial (審理不尽 - shinri fujin) and a flawed judgment.

Consequently, the Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for a new hearing specifically on the issue of the truck's market value at the time the avoidance power was exercised.

Context and Scholarly Discussion on Valuation Dates

The Supreme Court's consistent stance on using the "time of avoidance power exercise" as the valuation date for monetary restitution is one of several approaches debated in legal scholarship. Other proposed dates include:

- The time of the avoided act itself (aiming to restore the estate to its hypothetical state immediately before the wrongful transfer).

- The time of the beneficiary's disposal of the asset (if applicable, focusing on what the beneficiary realized or should have).

- The time of bankruptcy commencement (as the estate's composition is generally "fixed" at this point).

- The time of the conclusion of oral arguments in the avoidance lawsuit (argued by some for proximity to actual recovery and consistency with valuation in other contexts, like Civil Code fraudulent conveyance actions).

The Supreme Court's chosen date reflects a policy of trying to restore the value that the trustee could have obtained had the avoidance been immediately effective and the asset liquidated.

This case also serves as an important reminder of the court's procedural role. The duty of clarification (shakumeiken no kōshi) is a vital aspect of Japanese civil procedure, empowering and obligating judges to guide proceedings and ensure that parties have a fair opportunity to present all relevant aspects of their case, especially when a crucial point of proof (like valuation on a specific date determined during the trial) appears to be missing but potentially obtainable.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's April 3, 1986, judgment provides two key takeaways for understanding the consequences of bankruptcy avoidance in Japan:

- When an asset transferred pre-bankruptcy cannot be returned in specie and monetary restitution is sought, the value of that asset is to be determined based on its market value at the time the bankruptcy trustee exercises the right of avoidance. This aims to restore the realizable value to the estate.

- Courts have an affirmative duty to guide litigants. If a meritorious claim (like the right to monetary restitution) is established in principle, but specific proof of quantum for the correct valuation date is lacking—yet appears reasonably obtainable and has not been the central focus of prior dispute—the court should prompt the party to provide such evidence rather than dismissing the claim outright for lack of proof.

This balanced approach seeks to ensure not only that the bankruptcy estate is fairly compensated but also that the judicial process itself is conducted in a manner that facilitates a full and fair determination of the issues.