Valuing a Young Life: Japanese Supreme Court on Lost Earnings, Housework, and Gender Gaps in Wrongful Death Cases

Date of Judgment: January 19, 1987

Case Name: Claim for Damages

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

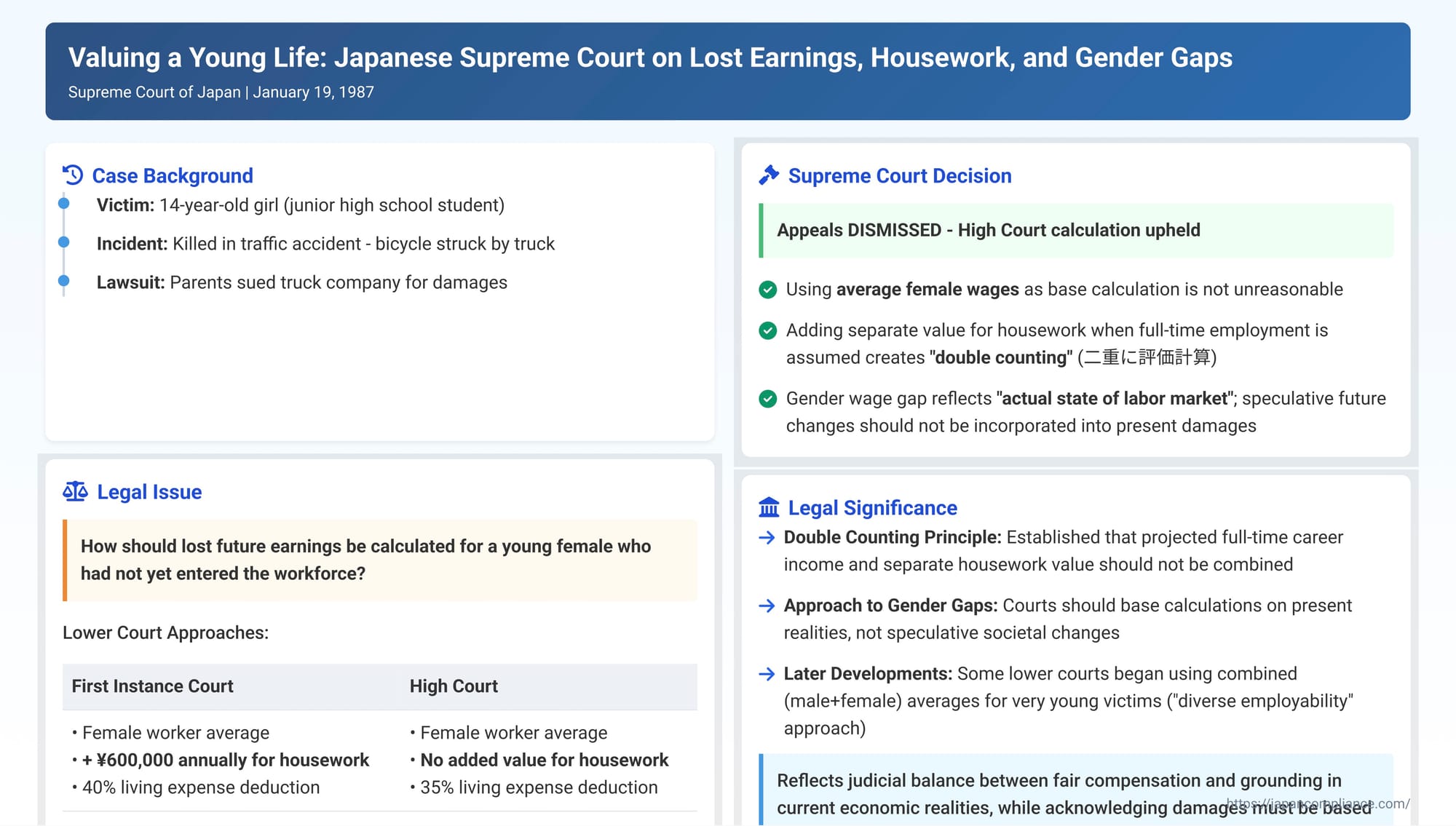

Placing a monetary value on a life tragically cut short is one of the most challenging tasks faced by legal systems. When a young person dies due to a wrongful act, a significant component of the damages claimed by their surviving family is "lost future earnings" – the income the deceased would likely have earned over their working life. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from January 19, 1987, addressed several complex aspects of this calculation in the case of a 14-year-old girl killed in a traffic accident. The judgment tackled how to project future income for someone yet to enter the workforce, whether to add a separate monetary value for potential future housework, and how courts should approach existing gender-based wage disparities in these calculations.

A Young Life Lost, A Future Unlived: The Factual Background

The case arose from a fatal traffic accident:

- The Victim and the Accident: A, a 14-year-old girl (a junior high school student at the time), was tragically killed when the bicycle she was riding was struck by a large truck owned by Y Company.

- The Lawsuit for Damages: A's parents (X et al.) sued Y Company for damages resulting from their daughter's wrongful death. A key element of their claim was compensation for A's lost future earnings.

- Differing Approaches in Lower Courts:

- The first instance court (Nagano District Court, Kiso Branch) calculated A's lost future earnings by:

- Using the average salary figures for female workers with junior high school or new senior high school educations, derived from the national wage census, as a base.

- Adding an annual sum of ¥600,000 to this base income to represent the value of A's potential future "housework labor" (家事労働分 - kaji rōdō bun) – the unpaid work she might have performed in maintaining a household.

- Applying a 40% deduction for presumed living expenses (a standard deduction in such calculations), the court arrived at a figure of over ¥23.31 million for lost future earnings. This, along with solatium (compensation for grief and suffering) for A and her parents, less any compulsory auto insurance payments received, formed the basis of the award against Y Company.

- The High Court (Tokyo High Court), on appeal by Y Company, took a different approach to calculating A's lost future earnings:

- It also used the average salary for female workers with similar educational prospects as the base income, assuming A would have pursued full-time employment until the standard retirement age of 67 and would have married in due course.

- However, the High Court did not add any separate monetary value for A's potential future housework.

- It applied a slightly different living expense deduction rate (35%). This resulted in a lower figure for lost future earnings, approximately ¥19.48 million. While the solatium amounts were similar to the first instance, the overall award was reduced due to the different calculation of lost earnings.

- The first instance court (Nagano District Court, Kiso Branch) calculated A's lost future earnings by:

X et al. (A's parents) appealed to the Supreme Court, specifically arguing that the High Court had erred by not including the value of A's potential future housework in the calculation of her lost future earnings.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court, on January 19, 1987, dismissed the parents' appeal. It upheld the High Court's method of calculating lost future earnings, which did not include an additional sum for housework when a full-time employment income was already being projected.

Core Rulings of the Supreme Court:

- Using Average Female Wages as a Base: The Court affirmed that the High Court's approach of using statistical average wage data for female workers with A's expected educational background (from the national wage census, specifically for full-time workers excluding part-timers) as the foundation for calculating her potential income was not unreasonable. The Supreme Court cited two of its prior decisions (from 1979 and 1981) that had found similar methods acceptable for determining lost future earnings for deceased young women.

- No Additional Compensation for Housework if Full-Time Employment Income is Assumed: This was the central point of the appeal. The Supreme Court ruled:

- When lost future earnings are calculated based on the premise that the deceased girl (A) would have engaged in full-time, specialized employment (専業として職業に就き - sengyō toshite shokugyō ni tsuki) and would have received a salary or wages for that work, then the economic benefit A could have obtained through her future labor is considered to be fully evaluated and encompassed by that projected employment income.

- Therefore, to add an additional monetary amount for "housework labor" (家事労働分 - kaji rōdō bun) on top of this projected employment income would amount to a "double evaluation or double counting" (二重に評価計算 - nijū ni hyōka keisan) of the benefits obtainable through her future labor. The Court deemed such double counting not appropriate.

- Addressing the Gender Wage Gap: The Court also touched upon the issue of the existing wage disparity between men and women as reflected in statistical averages:

- It acknowledged that the wage census data shows a gap between average male and female earnings, and stated that this gap is understood to reflect the "actual state of the labor market" (現実の労働市場における実態を反映 - genjitsu no rōdō shijō ni okeru jittai o han'ei) at that time.

- The Court reasoned that when calculating a young girl's lost future earnings for the purpose of a current damages award against a tortfeasor, it is "not necessarily rational" (必ずしも合理的なものであるとはいえない - kanarazushimo gōriteki na mono de aru towa ienai) to assume that the currently "unpredictable elimination or reduction of this gender wage gap will definitely occur in the future" and to incorporate such a speculative future change into the present damage calculation, thereby increasing the burden on the tortfeasor.

The Valuation of Lost Future Earnings: A Complex Calculation

This 1987 Supreme Court decision solidified a particular approach to calculating lost future earnings for young female decedents, while also reflecting the judiciary's cautious stance on directly addressing broader societal economic disparities through individual tort awards.

The "Double Counting" Rationale and Housework Valuation

The Supreme Court's primary justification for not adding a separate value for housework was the "double counting" argument. If a young woman is projected to have a full-time career and her lost earnings are calculated based on the income from that career, the Court viewed her labor potential as having been fully monetized through those projected wages. Adding a further sum for the unpaid housework she might also have performed was seen as compensating twice for the same underlying capacity to labor.

It's important to note that by this time, Japanese courts, including a landmark 1974 Supreme Court ruling, had already established that the unpaid labor of a full-time homemaker does have an economic value, and this value can be claimed as lost future earnings if the homemaker is killed or incapacitated. This value is often calculated by reference to average female wages. The 1987 case was distinct because it concerned a young girl for whom a full-time salaried career was being projected, raising the question of whether housework value could be an additional component.

Critiques and Alternative Perspectives

Legal commentators have discussed the "double counting" rationale. Some argue that the statistical average female wage used as a base might itself underrepresent the true economic contribution of women. This is because these averages reflect a labor market where women's wages are often lower than men's for various reasons, including potential career interruptions for family responsibilities, occupational segregation, or slower advancement. From this perspective, adding a component for housework might be seen not as double counting, but as a way to achieve a more holistic and fair valuation of a young woman's total lost economic potential, part of which might have been realized through paid employment and part through unpaid (but economically valuable) household labor.

The counter-argument, aligning with the Supreme Court's view, is that if the assumption is lifelong, full-time paid employment, that stream of income is the primary measure of her lost economic contribution through labor. Adding a separate, full valuation for housework could then arguably overcompensate compared to a male counterpart with an identical projected paid employment history.

The Gender Wage Gap in Damage Calculation

The Supreme Court's reluctance to proactively adjust damage awards to account for the potential future narrowing of the gender wage gap reflects a general judicial principle: damage calculations in tort cases are typically based on present realities and reasonably foreseeable future trends, rather than on speculation about broad societal changes. The Court indicated that it is not the role of an individual tortfeasor's liability to bear the cost of correcting systemic societal wage disparities, the resolution of which lies more in the realm of employment law, anti-discrimination policies, and broader social reforms.

Subsequent Developments: The "Diverse Employability" Logic

It is worth noting that in the years following this 1987 decision, particularly from the early 2000s, a significant trend emerged in Japanese lower courts regarding the calculation of lost future earnings for very young victims (both male and female) whose future career paths are entirely speculative.

- A number of influential High Court decisions (e.g., a Tokyo High Court ruling in 2001) began to advocate for using the average wage of all workers (male and female combined) as the basis for calculating lost earnings for young children.

- The rationale behind this "diverse employability" or "potential for various occupations" logic is that before a young person has made educational or career choices, their potential should not be limited by gender-specific statistical averages that reflect current, often segregated, labor market realities. Using an all-worker average is seen as a more gender-neutral and equitable way to value the lost economic potential of a child whose future is still wide open.

- While the Supreme Court has not issued a definitive, precedential ruling mandating this "all-worker average" approach for all young female victims, it has declined to overturn lower court judgments that have adopted it. This suggests a possible evolution in judicial thinking towards more gender-neutral calculations for the youngest victims, though the 1987 decision remains a key reference for the specific point it addressed regarding the non-addition of housework value to projected full-time employment income.

Conclusion

The 1987 Supreme Court decision concerning the lost future earnings of a deceased 14-year-old girl clarified two important aspects of damage calculation in wrongful death cases in Japan. First, it established that when a victim's lost earnings are calculated based on the assumption of a full-time salaried career, a separate monetary value for potential future housework should generally not be added, as this would constitute a "double counting" of their labor capacity. Second, the Court indicated that while existing gender-based wage disparities are a reality reflected in statistical data, it is not considered appropriate to adjust current tort damage awards based on speculative future changes to these societal gaps; compensation must be based on reasonably ascertainable present and future realities. While later judicial practice has explored more gender-neutral approaches for very young victims, this 1987 ruling remains an important precedent regarding the specific issues it addressed, reflecting the judiciary's careful approach to complex valuations and societal factors in the law of damages.