Supreme Court Clarifies LTCI Clawback: Valid Provider Designations Survive Initial Flaws (2011)

Japan Supreme Court (2011): Care benefits can’t be clawed back if the provider’s designation stays valid, despite flaws in its initial approval.

TL;DR

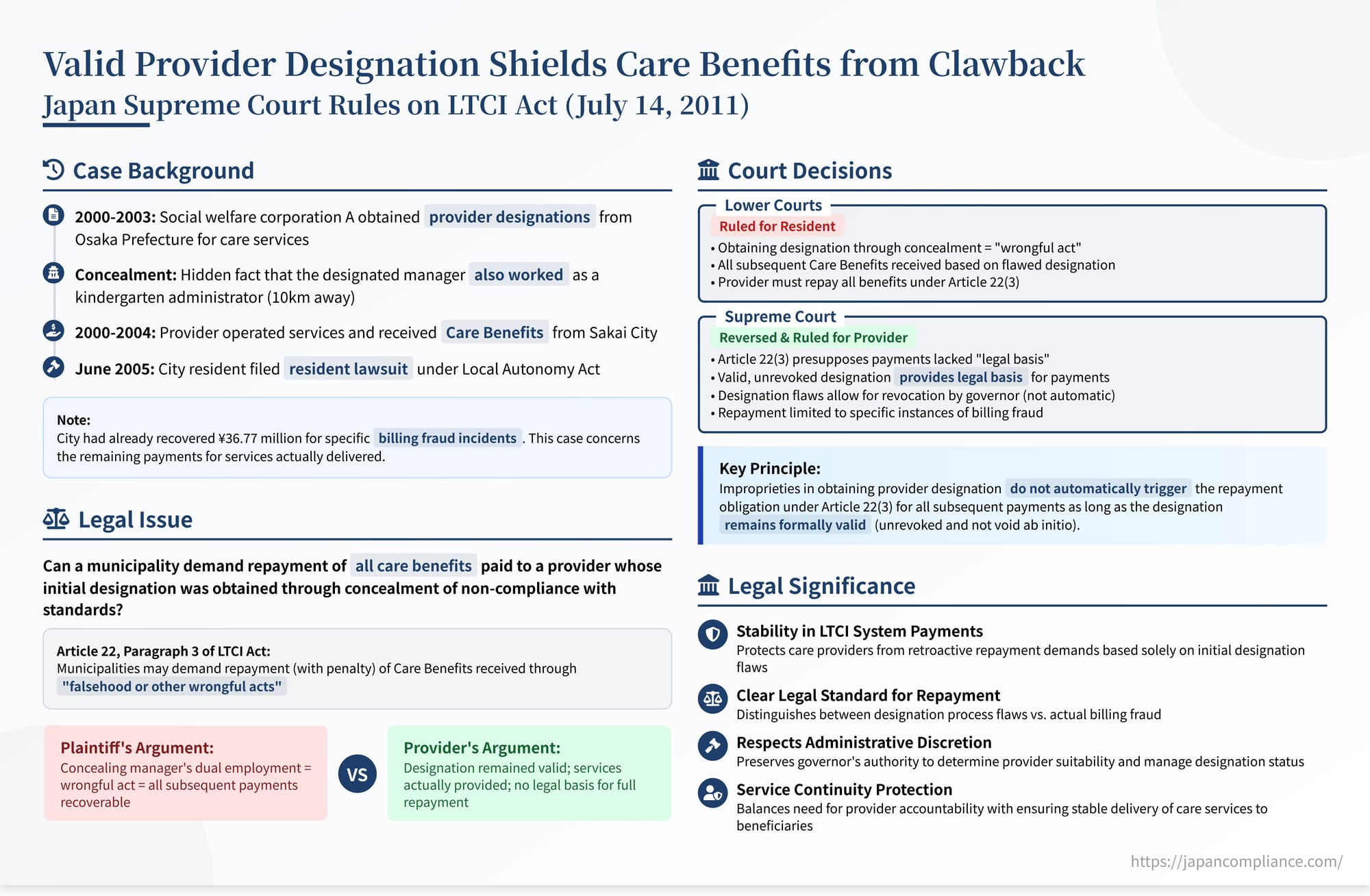

The 2011 Supreme Court ruling held that municipalities cannot demand repayment of long‑term care benefits solely because a provider concealed defects when first seeking designation. Unless the governor formally revokes the designation or it is void ab initio, payments for duly rendered services retain a legal basis.

Table of Contents

- Background: A Flawed Designation and a Resident's Lawsuit

- Lower Courts: Focus on the Wrongful Act of Obtaining Designation

- The Supreme Court's Analysis: Designation Validity is Key for Payment Legality

- Final Outcome and Significance

Japan's Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) system, established in 2000, relies significantly on private sector providers to deliver essential care services to the elderly. These providers – offering services like in-home assistance (visiting care, day care) or care management – must be formally designated (shitei) by the prefectural governor to be eligible for reimbursement from the system. Designated providers bill municipal insurers (cities, towns, villages) for the services rendered to eligible beneficiaries, and the municipality pays the corresponding fees, known as Care Benefits (kaigo hōshū).

To ensure quality and proper operation, providers must meet specific standards regarding personnel, facilities, and operations to obtain and maintain their designation. One such standard typically requires each service location to have a manager who is full-time and exclusively dedicated (senjū jōkin) to that role.

But what happens if a provider obtains its initial designation through improper means, for instance, by concealing information showing it doesn't meet a key standard like the manager requirement? If this provider then operates for years under that designation, providing actual services and receiving Care Benefits, can the municipality later demand repayment of all those benefits based solely on the initial flaw in the designation process? This question was central to a resident lawsuit decided by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 14, 2011, interpreting Article 22, Paragraph 3 of the LTCI Act (as it existed prior to a 2005 amendment). This provision allowed municipalities to demand repayment of Care Benefits received by a provider through "falsehood or other wrongful acts" (itsuwari sono ta fusei no kōi), along with a hefty penalty.

Background: A Flawed Designation and a Resident's Lawsuit

The case involved a social welfare corporation, A (the appellant intervenor), which operated several care service locations in Sakai City. In March 2000, A obtained designation from the Governor of Osaka Prefecture, B, for its visiting care service (Z1) and day care service (Z2) locations. In September 2003, it received designation for its care management service location (Z3). These designations allowed A to provide LTCI services and receive Care Benefits from Sakai City (represented by its Mayor, Y, the appellant).

However, the application materials submitted to Governor B for these designations contained a significant omission. They listed C (the husband of one of A's directors) as the manager for all three service locations. Crucially, C concurrently held a demanding position as the head administrator (jimuchō) of a kindergarten located approximately 10 kilometers away. This concurrent employment meant C did not satisfy the regulatory requirement that managers be full-time and exclusively dedicated to their duties at the designated service location. A's application failed to disclose C's kindergarten position, allegedly out of concern that revealing it would jeopardize the designations due to non-compliance with the manager standard.

Provider A operated the services under these designations and received Care Benefits from Sakai City for the fiscal years 2000 through 2004 (the "Period").

In June 2005, X, a resident of Sakai City (the appellee), initiated a resident lawsuit under the Local Autonomy Act. X argued that because C clearly did not meet the full-time manager requirement, the initial Designations granted by Governor B were fundamentally flawed, perhaps even invalid. Consequently, X claimed, all Care Benefits paid by Sakai City to Provider A during the Period, which were predicated on these flawed designations, constituted unjust enrichment. X demanded that the Mayor of Sakai City (Y) take action to recover the full amount of these benefits from Provider A, primarily invoking the clawback provision of LTCI Act Article 22(3).

It's important to note that, separately, Sakai City had already taken action against Provider A based on specific instances of fraudulent billing discovered during the Period (e.g., falsifying service records for visiting care, failing to apply required fee reductions for day care). The City demanded and received repayment for these specific improperly billed amounts, totaling roughly ¥36.77 million. The resident lawsuit, however, concerned the remaining Care Benefits paid during the Period – payments made for services actually rendered but under the cloud of the allegedly defective initial designations obtained by concealing the manager's true employment status.

Lower Courts: Focus on the Wrongful Act of Obtaining Designation

The lower courts focused on the provider's actions during the designation application process. Both the District Court and the High Court found that Provider A had intentionally concealed C's concurrent employment to obtain the designations, knowing it likely violated the manager standard. They concluded that obtaining the designations through such "wrongful means" meant that the subsequent receipt of Care Benefits, which depended on those designations, fell under the definition of receiving payment through "falsehood or other wrongful acts" in Article 22(3). Consequently, they ruled that Provider A was obligated to repay the remaining Care Benefits received during the Period. The Mayor (Y) and Provider A (as intervenor) appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: Designation Validity is Key for Payment Legality

The Supreme Court disagreed with the lower courts and overturned their decisions, ultimately dismissing the resident's claim regarding the designation flaw.

Relationship Between Payments, Unjust Enrichment, and Article 22(3):

The Court first clarified the legal framework for recovering Care Benefits. Payments are made by municipalities to designated providers based on meeting prescribed requirements and standards for the services delivered. If a payment is made without these conditions being met (e.g., overpayment, payment for services not rendered), the municipality generally has a right to seek restitution based on the principle of unjust enrichment (found in the Civil Code).

Article 22(3) of the LTCI Act, the Court interpreted, functions as a special provision (tokusoku) specifically addressing unjust enrichment claims related to Care Benefits when the provider employed "falsehood or other wrongful acts" in the process of receiving the payment. Crucially, the Court held that liability under this special provision presupposes that the underlying condition for unjust enrichment exists: namely, that the provider's receipt of the payment lacked a "legal basis" (hōritsu-jō no gen'in ga nai).

Impact of Designation Flaw vs. Designation Validity:

The core of the Court's reasoning lay in distinguishing between flaws in obtaining the initial designation and the legal basis for payments made while that designation was formally in effect.

- Provider A operated throughout the Period under designations that were formally granted by Governor B.

- The alleged wrongdoing (concealing C's employment) related to the application process for those designations.

- However, Governor B, the authority responsible for overseeing designations, had never revoked Provider A's designations based on this initial flaw (even though obtaining designation by "wrongful means" was a ground for revocation under Articles 77 and 84).

- Furthermore, the Court found that the concealment, while improper, did not constitute a defect so severe as to render the designations automatically void ab initio (invalid from the start).

The Ruling: No Lack of Legal Basis Merely from Designation Flaw:

Given that the Designations remained formally valid and unrevoked throughout the Period, the Supreme Court concluded that the Care Benefits paid by Sakai City to Provider A pursuant to those valid designations generally did have a legal basis at the time they were paid.

The Court reasoned that the mere fact that the initial designation was obtained through improper means does not, by itself, retroactively nullify the legal basis for payments received for legitimate services rendered while that designation was still officially recognized by the designating authority (Governor B). This implicitly distinguishes the situation from fraudulent billing, where the claim for payment for a specific service is itself false and thus clearly lacks a legal basis.

Since the payments in question (excluding those already recovered for specific billing fraud) had a legal basis stemming from the unrevoked designations, the prerequisite for applying the Article 22(3) clawback – a lack of legal basis for the payment – was not met. Therefore, Provider A was not obligated under Article 22(3) to repay these benefits solely because of the flaw in how the initial designations were obtained.

Supplementary Opinion on Administrative Discretion:

A supplementary opinion by one Justice reinforced this conclusion by highlighting the discretionary nature of designation revocation. The Governor has the power to revoke a designation (Art. 77, 84), but it's not automatic. The Governor must consider various factors, including the need to ensure service continuity for beneficiaries. Revocation is typically a measure of last resort, often preceded by guidance, audits, and opportunities for correction. The record indicated that Governor B had issued improvement guidance regarding the manager situation, and Provider A had subsequently appointed a new manager. Governor B's decision not to revoke the designation, likely based on a comprehensive assessment of provider suitability and user needs, should be respected. Allowing a court, through a resident lawsuit focused on Art. 22(3), to compel repayment based solely on the initial designation defect would effectively produce the same outcome as designation revocation, thereby improperly overriding the Governor's administrative discretion.

Final Outcome and Significance

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court judgment that had favored the resident plaintiff. It cancelled the first instance judgment (which had also favored the plaintiff on this point) and dismissed the plaintiff's claim seeking repayment based on the initial designation flaw.

This 2011 decision establishes an important principle regarding the stability of payments under Japan's LTCI system. It holds that improprieties in obtaining a provider designation do not automatically trigger the clawback provision of Article 22(3) for all subsequent payments as long as the designation remains formally valid (i.e., unrevoked by the designating authority and not void ab initio). Liability under Article 22(3) requires demonstrating that the payment itself lacked a legal basis, typically involving fraud or error in the billing for specific services, rather than solely relying on defects in the initial designation process.

The ruling underscores the significance of the formal administrative act of designation and the discretionary power of the prefectural governor to manage provider status, including decisions on revocation. It suggests that challenges related to initial designation flaws should primarily be addressed through the administrative procedures governing designation (e.g., seeking revocation by the governor), rather than through Article 22(3) repayment demands concerning payments made while the designation was active. This approach prioritizes the continuity and stability of services funded through the LTCI system, while still allowing for recovery of payments based on direct billing fraud. However, it also raises ongoing questions about ensuring full accountability for providers who initially enter the system through deceptive means.

- Workers' Comp vs. Consolation Money: Japan’s Supreme Court Separates Financial and Non‑Financial Damages (1966)

- Japan’s Immigration Overhaul: What the 2023 Amendments Mean for Global Mobility & CSR

- Perfecting Rights to Standing Timber in Japan: The Enduring Requirement of “Meinin Hōhō”

- Long‑Term Care Insurance in Japan | Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare