Vaccine Injury in Japan: Supreme Court Eases Burden of Proof for Victims in Landmark Case

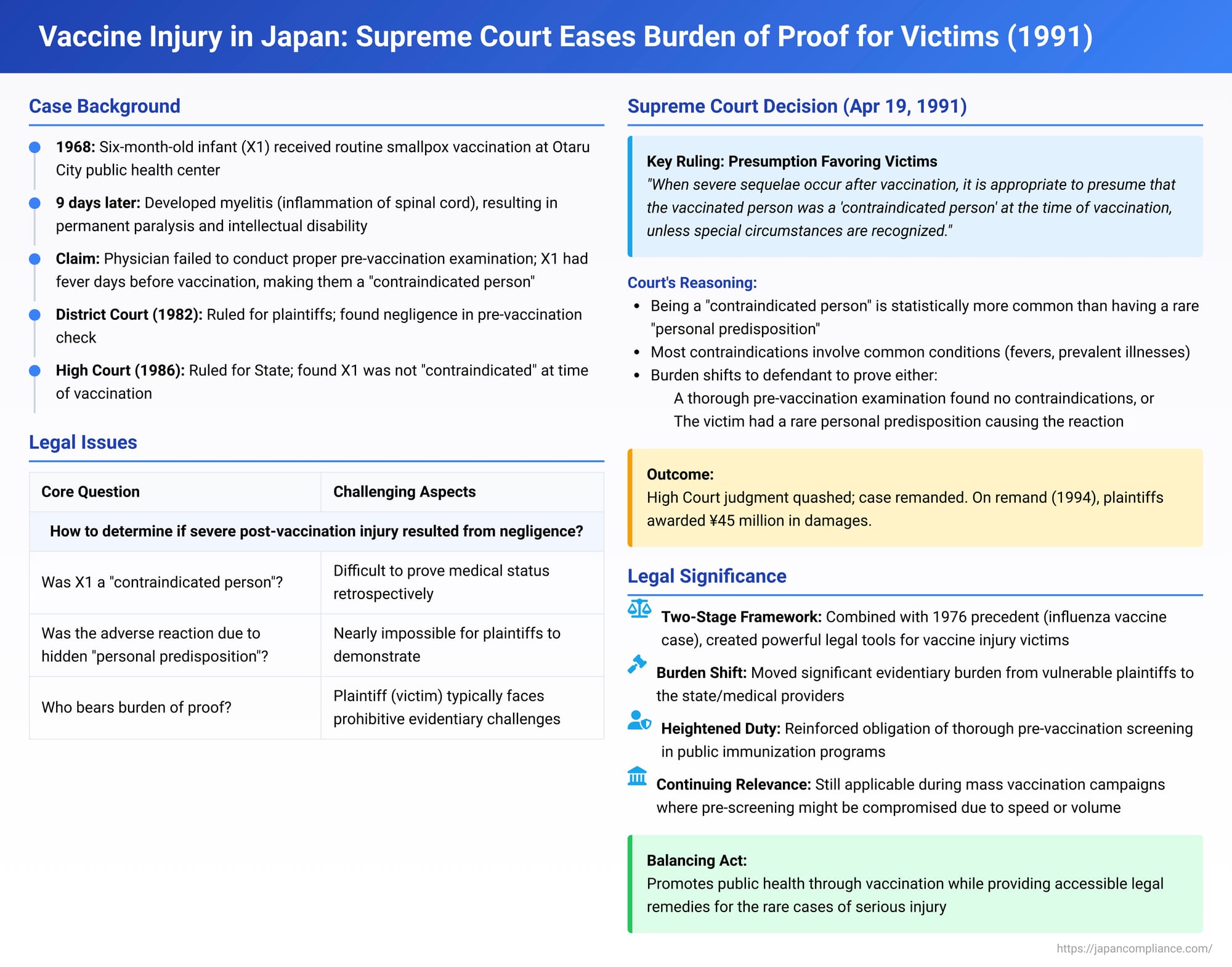

Vaccinations are a cornerstone of public health, preventing the spread of infectious diseases. However, in rare instances, they can lead to severe adverse reactions. For individuals and families affected, seeking legal redress can be a daunting task, often involving complex medical evidence and questions of causation and negligence. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 19, 1991 (Showa 61 (O) No. 1493), in what is often referred to as the "Smallpox Vaccination Sequelae Case," significantly impacted this area of law by establishing a key presumption to aid victims.

The Smallpox Vaccine and Its Devastating Aftermath: Case Background

In 1968, Plaintiff X1, then a six-month-old infant, received a routine smallpox vaccination (shutō) at a public health center in Otaru City, Hokkaido. Tragically, nine days after the vaccination, X1 developed myelitis, an inflammation of the spinal cord. This resulted in permanent and severe neurological damage, including paralysis of the lower body and intellectual disability.

The child's parents, along with X1 (collectively, Plaintiffs X), initiated a lawsuit against the Japanese State and Otaru City (Defendants Y), seeking damages of approximately 65 million yen under the State Compensation Act. Their central allegation was that the physician in charge at the public health center had been negligent in the pre-vaccination examination (yoshin). Specifically, they argued that X1 had exhibited a fever a few days prior to the vaccination, a condition that should have identified X1 as a "contraindicated person" (kinkisha)—an individual for whom vaccination was medically inadvisable at that time. They claimed this critical fact was overlooked due to an insufficient pre-vaccination screening.

The Legal Battle: From Compensation to Dismissal, and Back to the Supreme Court

The case had a tumultuous journey through the lower courts:

- First Instance (Sapporo District Court, October 26, 1982): The District Court ruled in favor of Plaintiffs X. It found a causal link between the smallpox vaccination and X1's subsequent neurological injuries. Furthermore, it determined that the physician had breached the duty of inquiry (monshin gimu) during the pre-vaccination check by failing to adequately ascertain X1's health status, thereby overlooking X1's unsuitable condition for vaccination. The court found the State and City liable for negligence and awarded approximately 34 million yen in damages.

- Appellate Court (Sapporo High Court, July 31, 1986): The High Court reversed the District Court's decision and dismissed the plaintiffs' claims. While it affirmed the causal connection between the vaccination and the injuries, it concluded that X1's pharyngitis (the cause of the earlier fever) had resolved by the day of the vaccination. Therefore, the High Court found that X1 was not a contraindicated person and was, in fact, fit for vaccination at the time. Consequently, even if there were shortcomings in the pre-vaccination examination, these were deemed causally irrelevant to the tragic outcome.

Plaintiffs X appealed this appellate decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (April 19, 1991): A Presumption in Favor of Victims

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for reconsideration. The crux of its landmark ruling was the establishment of a rebuttable presumption concerning the cause of severe post-vaccination injuries.

The Core Problem and the Court's Insight:

When severe adverse neurological reactions follow a vaccination, establishing the precise cause is often medically complex. The Supreme Court identified two primary possibilities:

- The individual was a "contraindicated person": They had a temporary or underlying condition (such as fever, certain acute or chronic illnesses, or specific allergies, as outlined in vaccination guidelines) that made receiving the vaccine unsafe at that particular time.

- The individual had a rare, often undetectable, "personal predisposition" (kojin teki soin) to react severely to the vaccine, a factor that standard pre-vaccination checks might not uncover.

The Supreme Court reasoned that the conditions making someone a "contraindicated person" are generally common (e.g., temporary fevers, prevalent illnesses, common allergies). In contrast, a hidden "personal predisposition" making someone uniquely vulnerable to severe vaccine reactions is, by its nature, far less common. Therefore, the Court found, "the probability of an individual being a 'contraindicated person' should be considered far greater than the probability of having such a 'personal predisposition'."

The Presumption Established:

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court established the following critical presumption:

"Therefore, if severe sequelae occur after a vaccination, there is a high probability that these sequelae occurred because the said vaccinated person was a 'contraindicated person'. Accordingly, when such severe sequelae result from a vaccination, it is appropriate to presume that the vaccinated person was a 'contraindicated person' at the time of the vaccination, unless special circumstances are recognized."

Rebutting the Presumption:

This presumption is not absolute and can be rebutted by the defendants (the state or administering body). The "special circumstances" that could rebut this presumption primarily include:

- Proof that "the pre-vaccination examination necessary to identify contraindicated persons was fully performed, but no grounds for recognizing the person as contraindicated could be found."

- Proof that "the vaccinated person had such a personal predisposition" that caused the reaction.

Implication for the Case at Hand:

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred by concluding X1 was fit for vaccination without sufficiently examining whether the pre-vaccination check conducted by the public health center physician had been adequate to identify potential contraindications. The Supreme Court thus remanded the case, directing the High Court to fully examine this issue in light of the newly established presumption.

Building on Precedent: The Link to Negligence

This 1991 Supreme Court ruling on presuming "contraindicated status" built upon and complemented an earlier significant Supreme Court precedent from September 30, 1976 (Showa 51), which dealt with a death following an influenza vaccination.

The 1976 ruling had established that:

- Physicians administering vaccinations have a duty to conduct a careful pre-vaccination examination, including a thorough inquiry (monshin) into the patient's health history and current condition, to identify any contraindications as specified in then-existing immunization regulations.

- If a physician, due to an inadequate inquiry, fails to recognize that a person is contraindicated for a vaccine, proceeds with the vaccination, and the person subsequently suffers a severe adverse reaction (such as death or serious illness), then "it is appropriate to presume that the attending physician could have foreseen such a result but failed to do so due to error (negligence)."

Combined Effect of the Two Rulings:

Together, the 1976 and 1991 Supreme Court decisions created a powerful two-stage framework that significantly aided plaintiffs in vaccine injury cases:

- Presumption of Contraindicated Status (1991 Ruling): If a plaintiff proves that severe harm occurred as a consequence of a vaccination, it is presumed that the plaintiff was a "contraindicated person" at the time of the vaccination. The burden then shifts to the defendant to prove "special circumstances" (e.g., a flawless pre-vaccination check found no contraindications, or a rare personal predisposition was the cause).

- Presumption of Negligent Failure to Foresee Harm (1976 Ruling): If it is established (or presumed and not rebutted) that the person was contraindicated, and if the plaintiff further proves that the pre-vaccination inquiry was inadequate, then it is presumed that the physician negligently failed to foresee the potential for harm.

This framework effectively shifted a substantial evidentiary burden from the often vulnerable plaintiff to the state or medical provider, who are typically in a better position to provide evidence regarding the procedures followed.

Impact and Legacy of the Rulings

These Supreme Court decisions were particularly instrumental in providing avenues for redress for many victims of adverse vaccination reactions during an era in Japan characterized by mass public immunization campaigns, where pre-vaccination checks might have been less thorough than ideal.

- The rulings recognized the immense difficulty faced by individual plaintiffs in scientifically proving the precise medical mechanism of their injury or the exact nature of their contraindication after the event.

- The presumption of "contraindicated status" helped to level the playing field in litigation.

- Relevance Today: The commentary accompanying the 1991 judgment notes that while routine childhood vaccinations in more recent times often involve more individualized pre-screening in clinical settings, the legal principles established by these cases remain pertinent. It suggests that in any situation involving mass vaccination efforts where pre-vaccination checks might be compromised due to speed or volume—as could be a concern, for example, during emergency public health campaigns like the COVID-19 pandemic response—these precedents could once again become central to legal claims for compensation if adverse events occur due to inadequate screening.

- It is important to remember that the plaintiff still bears the initial burden of proving, to a standard of "high probability," a factual causal link between the vaccination and the subsequent injury. This itself can be a significant challenge in many vaccine injury cases.

What Happened on Remand (Again)?

Following this 1991 Supreme Court decision, the case was returned to the Sapporo High Court. On December 6, 1994, the High Court on remand found that the defendants had not succeeded in proving the "special circumstances" necessary to rebut the presumption that X1 was a contraindicated person. Consequently, it upheld the original first instance judgment that had found the defendants liable, awarding the plaintiffs approximately 45 million yen in damages. This judgment became final.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1991 decision in the Smallpox Vaccination Sequelae Case, particularly when viewed in conjunction with its 1976 precedent, marked a compassionate and pragmatic shift in the legal landscape for vaccine injury claims. By establishing a rebuttable presumption that severe post-vaccination harm implies the recipient was medically contraindicated for the vaccine at that time, the Court significantly eased the often insurmountable burden of proof faced by victims and their families. These rulings underscore the profound responsibility of health authorities and medical professionals administering public immunization programs to ensure that pre-vaccination safety checks are conducted with the utmost diligence and care.